Introduction

The facelift, or rhytidectomy, was the third most commonly performed cosmetic surgical procedure in the United States in 2020, after rhinoplasty and blepharoplasty. Aging causes skin and soft tissue descent as well as lipoatrophy that leads to tear trough deformities, deep palpebromalar grooves, loss of malar volume, descent of the jowls, pronounced nasolabial folds, and development of marionette lines. Facelifting ideally repositions descended soft tissue superiorly to restore facial volume and a more youthful appearance. Throughout the years, facelifting has evolved from simple skin crease cutting to the minimal access cranial suspension and the more sophisticated superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) manipulation. Multiple methods of facelifting currently exist, and each method is tailored to the individual patient's needs and a plastic surgeon’s expertise.[1][2]

The head and neck region has five major soft tissue layers; from superficial to deep, those are: skin, subcutaneous fat, superficial fascia, loose aponeurotic tissue, and deep fascia. The superficial fascia is often known as the SMAS, depending on the region of the face. The extended SMAS technique involves dissection in a sub-SMAS fashion and suspending the SMAS posterosuperiorly. The reason for the term “extended” is that this technique dissects the SMAS more thoroughly and distally than any other technique. Additionally, the extended SMAS technique provides midface rejuvenation, while other SMAS techniques do not necessarily enhance the midface. Midface volume augmentation is achieved by transferring sunken tissue cephalad to enhance facial volume and malar augmentation, and hence to produce a more youthful appearance.[3][4][5][6][7]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

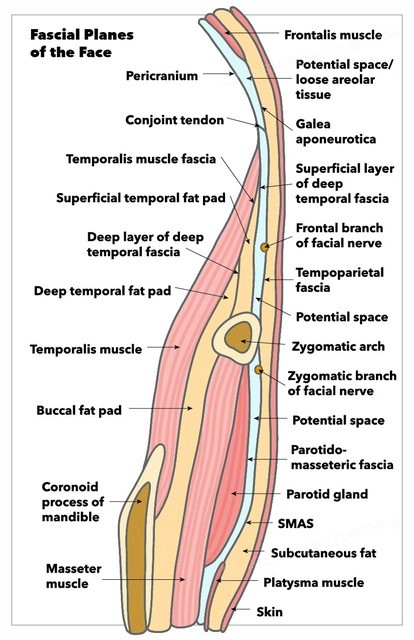

The head and neck region contains five important fascial layers, with which any surgeon working in the area must be very familiar. From superficial to deep, these are the skin, the subcutaneous tissue/superficial areolar tissue, the superficial fascia, the loose areolar tissue, and the deep fascia. At the level of the midface, the superficial fascia is termed the superficial musculoaponeurotic system, or SMAS. The third layer’s nomenclature differs depending on the area; it is the frontalis muscle in the forehead, the temporoparietal fascia in the temporal region, the SMAS in the midface, and the platysma in the neck. The deep fascial layers also have different nomenclature depending where in the face and neck they are identified. These are the deep temporal fascia or temporalis muscle fascia, the parotidomasseteric fascia, the periosteum under the scalp, and the deep cervical investing fascia in the neck.

The SMAS varies in thickness depending on the region of the face, with denser tissue in the lateral face and thinner tissue medially. The SMAS also typically has tighter adhesions to the skin, and looser adhesions to the fifth layer, allowing for sub-SMAS blunt dissection. Fibrous connections, referred to as the facial or retaining ligaments, are important because they give support and stability to the surrounding layers. There are two types, the osseocutaneous ligaments and ligaments that connect between the third and fifth layers. These ligaments are surgically released during tissue dissection in a facelift to permit mobilization of flaps, and their function is then restored with sutures. The most important ligaments in the face include the temporal ligamentous adhesion, the lateral orbital thickening, the zygomatic ligament, the masseteric ligaments, and the mandibular ligament.

The modiolar peninsula is the perioral area in the face above the mandibular ligament and below the zygomatic ligament. This area is never dissected during the extended SMAS technique. It sometimes serves as an anchoring site for sutures to bring this tissue cephalad.

Superficial fat in the midface is termed "malar fat." This fat gives the face volume and a youthful appearance. One of the benefits of the extended SMAS technique is that this volume is returned to the midface and the malar prominence is enhanced.

Branches of the facial nerve have different courses after traversing the parotid gland. After exiting the anterior border of the parotid, these branches travel just superficial to the masseteric fascia. The facial nerve branches generally then travel along the deep surfaces of the facial muscles to provide innervation; the exceptions are the mentalis, levator anguli oris, and buccinator muscles, which are innervated from their superficial surfaces because they are located deeper within the face. This arrangment is important to keep in mind to avoid injury to nerves during dissection. It is also important to be cognizant of each branch’s trajectory through the face. More commonly injured than the facial nerve's branches, however, is the great auricular nerve, which exits the posterior aspect of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and travels superiorly roughly mid-way between the mastoid tip and the angle of the mandible, 1-2 cm posterior to the external jugular vein.[4][5][6][7][8]

Indications

Any patient with an aging face and an interest in rejuvenation can be considered a candidate for surgery. Specifically, patients with loss of malar volume will benefit from the extended SMAS facelift. It is also imperative to evaluate motives and counsel patients regarding realistic expectations. Ideally, a patient will understand the risks of surgery and will expect to improve his or her appearance but not demand perfection.

Contraindications

There are a few relative contraindications for the extended SMAS technique. Nicotine use, keloid formation, anticoagulation, previous deep plane rhytidectomy, and unrealistic expectations are some examples. Some patients might also benefit from other facelift techniques rather than the extended SMAS. For instance, patients with a youthful appearing midface should not be offered this procedure. It is important to assess psychiatric comorbidities, medical contraindications, and life situations that may lead to complications. Patients with a narcissistic personality disorder, body dysmorphic disorder, and other psychiatric disorders should seek psychiatric evaluation and treatment before the intervention or even avoid cosmetic procedures at all. The high rate of postoperative depression that occurs with facelifting means that patients with an history of depression should be counseled appropriately, and the procedure delayed if pharmacotherapy needs to be initiated preoperatively.[9][10]

Equipment

While different surgeons and different institutions will have different instrument sets available, extended SMAS rhytidectomy typically requires a #10 and a #15 blade scalpel, facelift retractor and light source, facelift scissors, Trepsat dissectors, needle drivers, forceps, electrocautery, suction, and sutures for both soft tissue suspension and skin closure. Heavy 2-0 polyglactin sutures are used to suspend the SMAS flap. Finer 5-0 polypropylene is used for skin closure anterior to the auricle, and 4-0 to 6-0 absorbable sutures, such as plain gut, are used to close the remainder of the incision. A bulky compression dressing is typically applied at the conclusion of the procedure.

Personnel

Because of the comprehensive nature of this procedure and the fact that facelifting is often accompanied by other cosmetic surgical procedures, such as blepharoplasty, liposuction, skin resurfacing, and/or brow lifting, general anesthesia or at least deep sedation is preferred. In addition to the anesthesia provider, an operating room nurse and a surgical technician are required, and a first assistant will make the surgeon's job much easier. Postoperatively, outpatient nursing staff will be critical for wound care, suture removal, and patient support, without which the outcomes will be suboptimal.

Preparation

In preparation for the facelift, the patient should be encouraged to stop smoking at least 3 to 4 weeks before the surgery. Patients should also be instructed to discontinue any anticoagulation, if possible, before surgery to avoid postoperative hematomas and reduce intraoperative blood loss. During the preoperative visit, the plastic surgeon should document any facial asymmetry, as well as the preoperative function of cranial nerves five and seven, and the great auricular nerve. Lastly, the patient should be positioned upright to appreciate the extent of soft tissue descent and plan the surgery.

A marker should be used to delineate the path of the intended incisions and flap elevation. Some physicians will mark the zygomatic ligament, the zygomaticus major muscle, the mandibular ligament, and the SMAS. The path of the great auricular nerve or the temporal branch of the facial nerve can also be marked preemptively to avoid injury during the surgery.[4]

Technique or Treatment

For the extended SMAS technique, the patient should be placed under general anesthesia or deep sedation. The patient should be arranged in a supine position, and the surgical table should be rotated if possible to allow for more comfortable access to the patient’s face. At this time, the patient’s face and neck should be prepped and draped in the usual sterile fashion. Traditional tumescent solution may be infiltrated along the planned incisions while attempting to avoid distortion of the tissues. A mixture of 0.25% bupivacaine and 0.5% lidocaine can also be injected in the plane of the intended flap elevation to achieve hydrodissection and hemostasis.

A beveled incision is made with a #10 blade at the temporal hairline to preserve hair follicles; electrocautery in coagulation mode may be used for hemostasis, while avoiding hair follicles in order to prevent alopecia. The incision then travels caudally into a posttragal incision in females (pretragal in males), curves around the ear into the postauricular sulcus, and then runs along the posterior hairline. Male patients should be informed that posttragal incisions will bring bearded skin to the tragus, so the pretragal is the preferred incision.

After the incision is completed, a skin flap is elevated anteriorly towards the cheek, and inferiorly from the mastoid towards the neck; this dissection takes place subcutaneously, above the SMAS and third layer. Flap dissection is, on average, carried 4 cm radially from the inferior aspect of the tragus. Raising this flap too thick may lead to a weak SMAS flap, whereas raising this flap too thin may compromise the vascularity of the skin. Mindful dissection must also be done to not damage the main trunk of the great auricular nerve, which lies above the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Jowl fat should be kept on the SMAS, so this can be repositioned cephalad eventually when raising the SMAS flap.[4]

The SMAS is incised horizontally over the zygomatic arch and then caudally, extending from 2 cm anterior to the tragus to just behind the angle of the mandible. At this time, the tissue is undermined through the sub-SMAS plane. Most of the dissection can be carried out with careful spreading of scissors or the Trepsat facial dissectors. Once platysmal muscle fibers are identified, blunt dissection can be performed in the subplatysmal plane; lateral platysmal attachments should be released.

Dissection continues anteriorly in the face over the masseteric muscle, releasing the masseteric ligaments. The buccal fat pad, or the boule of Bichat, is usually seen in the anterior aspect of the dissection, having an “egg yolk” appearance. Treatment of the fat pad can be done at this time if needed. The dissection is then turned to the zygomatic area. Dissection is performed in the sub-SMAS plane just below the orbicularis oculi muscle and over the distal third of the zygoma to avoid the temporal branch of the facial nerve. Also, care must be taken to stay over the zygoma and avoid its inferior border. The temporal branch of the facial nerves lies about 1 cm anterior to the tragus, and a midfacial branch runs parallel to the zygomatic arch to innervate the zygomaticus major muscle.

Careful hemostasis with bipolar cautery, if needed, can be performed in these areas if the bleeding is significant, but it is best avoided. Through this dissection, the zygomatic ligament is released using electrocautery or cold instruments; dissection should stay over the zygomaticus major muscle. From the midface, the dissection should continue inferiorly over the parotidomasseteric fascia to join the previously developed inferior flap. Once joined, the flaps should be dissected anteriorly until all ligaments are released. When indicated, a submental incision is occasionally used to release the mandibular ligament, perform submental lipectomy, subplatysmal fat dissection, and partial digastric muscle resection. The modiolar peninsula is excluded from the dissection. At all times, an assistant is observing the face for muscle movements.

After the dissection culminates and definitive hemostasis is achieved, the flap can be mobilized and fixated. The SMAS is pulled and anchored to the pre-tragal area, and posteriorly to the mastoid periosteum. Polyglactin 2-0 suture is used for suspension. About 10 to 12 sutures are placed on each side, fixating the SMAS and platysma. Careful trimming of the jowl fat and submandibular fat can be performed to enhance the jawline and add volume to the face. The skin must then be checked for dimples; occasionally, additional supra-SMAS dissection must be performed to eliminate these. Excess skin is excised with a #15 blade.

Burow's triangles may be used to bring the skin edges together smoothly. The incision is then closed by placing 5-0 polypropylene at the root of the helix and the cephalad part of the postauricular incision. The rest of the incisions are then closed with sutures depending on the surgeon's preference. Usually, 4-0, 5-0, or 6-0 absorbable sutures are utilized. Once finished, a topical antibiotic is applied to the incisions, and a compression dressing is placed.[4][8]

Complications

Complications of the extended SMAS facelift are similar to other rhytidectomies. These include hematomas, seromas, edema, great auricular nerve damage, facial nerve branch damage, transient neurapraxia, unfavorable scars, altered hairlines, pixie ear deformity or deformity of the tragus, wound infections, and deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Hematomas are among the most feared complications of facelifting due to the risk of subsequent flap necrosis, and sometimes even airway compromise. The most common adverse event after extended SMAS rhytidectomy is patient dissatisfaction.[4]

Clinical Significance

Each facelift technique must be tailored to a patient’s individual needs. The extended SMAS technique is beneficial for patients who require midface rejuvenation along with the lower face and neck. The firm texture of the SMAS allows for less recurrence, less skin tension, and more stability of the facelift. This technique allows the SMAS to the carry tension applied to the face, while the skin overlies the flap without tension on the incisions. Excess skin that is brought up is then removed. By bringing this layer cephalad, the patient receives increased facial volume, enhanced malar prominence, and a smooth jawline that lead to a youthful appearance and hence increased patient and surgeon satisfaction.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Facelifts overall should be attempted cautiously; careful assessment by the physician and nursing staff is required. The initial encounter must include a thorough medical evaluation. The physician should be able to determine which facelift technique benefits the patient the most. The patient should endeavor to understand every risk posed by the surgery, including that of dissatisfaction, even in the setting of a technically successful facelift. There are times when surgery alone might not be able to achieve the desired result, and fillers or neuromodulators may supplement the operation. A minority of patients may have body dysmorphic disorder or other disorders that warrant specialist evaluation before surgery.

Expectations must be communicated and understood before performing a facelift. Postoperative pain control should also be discussed before and after the surgery with the patient and a pharmacist. Coordination among the surgeon, nursing staff, and pharmacist will improve outcomes, lower complication rates, and contribute to higher patient satisfaction.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Fascial Planes of the Face. This illustration shows the fascial planes of the face while demonstrating the continuity of the frontalis muscle, galea aponeurotica, temporoparietal fascia, superficial musculoaponeurotic system, platysma, and facial nerve's location.

Contributed by K Humphreys and MH Hohman, MD, FACS

References

Cakmak O, Emre IE. Surgical Anatomy for Extended Facelift Techniques. Facial plastic surgery : FPS. 2020 Jun:36(3):309-316. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1712472. Epub 2020 Jun 17 [PubMed PMID: 32557438]

Quatela V, Montague A, Manning JP, Antunes M. Extended Superficial Musculoaponeurotic System Flap Rhytidectomy. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2020 Aug:28(3):303-310. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2020.03.007. Epub 2020 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 32503716]

Buchanan PJ, Mihora DC, Mast BA. Facelift Practice Evolution: Objective Implementation of New Surgical Techniques. Annals of plastic surgery. 2018 Jun:80(6S Suppl 6):S324-S327. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001321. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29369107]

Charafeddine AH, Zins JE. The Extended Superficial Musculoaponeurotic System. Clinics in plastic surgery. 2019 Oct:46(4):533-546. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2019.05.002. Epub 2019 Jul 18 [PubMed PMID: 31514806]

Sykes JM, Riedler KL, Cotofana S, Palhazi P. Superficial and Deep Facial Anatomy and Its Implications for Rhytidectomy. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2020 Aug:28(3):243-251. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2020.03.005. Epub 2020 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 32503712]

Damitz LA. The Utility of Superficial Musculoaponeurotic System Flaps in Facelift Procedures. Annals of plastic surgery. 2018 Jun:80(6S Suppl 6):S406-S409. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001344. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29668506]

Jacono A, Bryant LM. Extended Deep Plane Facelift: Incorporating Facial Retaining Ligament Release and Composite Flap Shifts to Maximize Midface, Jawline and Neck Rejuvenation. Clinics in plastic surgery. 2018 Oct:45(4):527-554. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2018.06.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30268241]

Gordon NA, Adam SI 3rd. Deep plane face lifting for midface rejuvenation. Clinics in plastic surgery. 2015 Jan:42(1):129-42. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2014.08.009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25440750]

Adamson PA, Chen T. The dangerous dozen--avoiding potential problem patients in cosmetic surgery. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2008 May:16(2):195-202, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2007.11.010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18355705]

Hönig JF. [Concepts in face lifts. State of the art]. Mund-, Kiefer- und Gesichtschirurgie : MKG. 1997 May:1 Suppl 1():S21-6 [PubMed PMID: 9424371]