Introduction

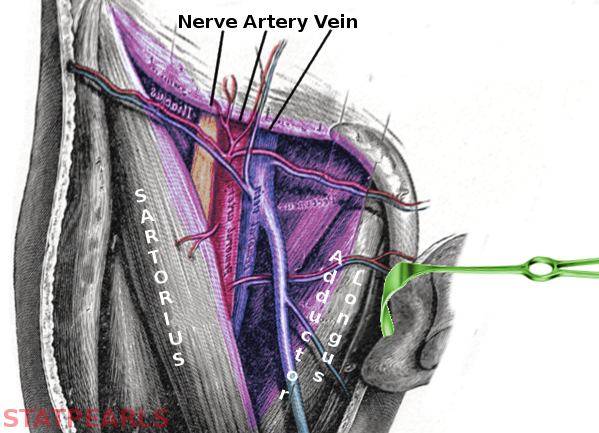

The femoral triangle in the anterior superior third of the thigh is a subfascial space that appears as a triangular depression inferior to the inguinal ligament; the depression is visible when the thigh is abducted, flexed, and laterally rotated. The borders of the femoral triangle are the inguinal ligament superiorly, the adductor longus muscle medially, and the sartorius muscle laterally. The apex of the triangle is located distally and is formed by the intersection of the lateral border of the femoral triangle, the sartorius, crossing over the medial border of the triangle, the adductor longus. See Image. Femoral Triangle.

The floor of the femoral triangle is composed of several muscles; medially, the floor is formed by the pectineus and adductor longus and laterally by the iliopsoas. The roof of the femoral triangle, from superficial to deep, is composed of skin, subcutaneous tissue, superficial fascia, and deep fascia (fascia lata).

From lateral to medial, the contents of the femoral triangle include the femoral nerve, femoral artery, femoral vein, and lymphatics. A convenient mnemonic is NAVEL: femoral Nerve, femoral Artery, femoral Vein, and Empty space with Lymphatics (femoral canal). The femoral artery, femoral vein, and deep inguinal lymph nodes with associated lymphatics are within a conical fascial sheath, the femoral sheath. The femoral sheath is continuous with the transversalis fascia of the abdomen and the inguinal ligament; it encases the vessels as they pass through the femoral triangle.[1]

The femoral sheath merges inferiorly with connective tissue associated with the vessels. Each vessel has a separate sub-compartment of the femoral sheath as it passes through the femoral triangle. The femoral nerve is not contained within the sheath.[1]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Structure of the Femoral Triangle

- Superior border - inguinal ligament

- Medial border - adductor longus muscle

- Lateral border - sartorius muscle

- Medial floor - adductor longus and pectineus muscles

- Lateral floor - iliopsoas muscle

- Roof - (from superficial to deep) skin, subcutaneous tissue, superficial fascia, and fascia lata

- Internal structures - (from lateral to medial) femoral nerve, femoral artery, femoral vein, deep inguinal lymph nodes, and associated lymphatic vessels (see Image. Femoral Triangle Structures)

Function of the Femoral Triangle

The femoral triangle itself does not have an intrinsic function but contains many vital structures that can be located quickly using the landmarks of the femoral triangle. The muscles that form the borders of the triangle also allow many different movements.

Embryology

The extremities of the body initially form as limb buds containing an outer layer of ectoderm with an inner layer of mesoderm. The lower limbs begin development after the upper limbs, at about week 4 of gestation, with all limbs being well differentiated by about 8 to 10 weeks gestational age.[2]

The muscles and fascia of the femoral triangle derive from mesoderm contained within developing limb buds at the time of extremity formation.

The blood vessels and the lymphatics of the femoral triangle are also derived from mesoderm.

The epidermis above the femoral triangle and the femoral nerve are formed from the ectoderm contained in limb buds at the time of extremity formation.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

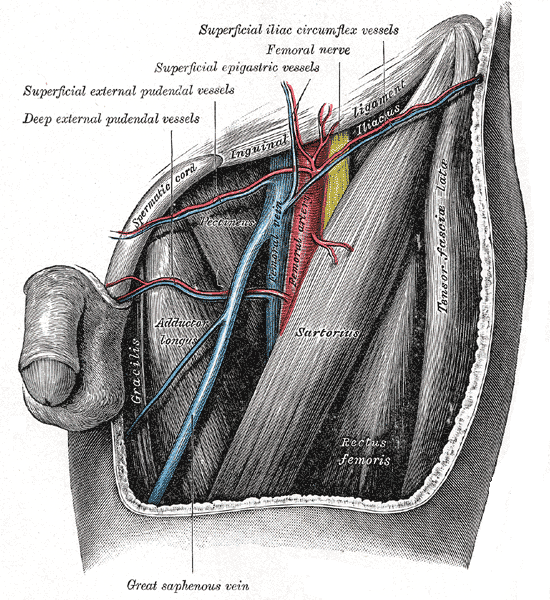

The major vessels that run through the femoral triangle include the femoral artery and femoral vein. In the area of the femoral triangle, the great saphenous vein connects to the femoral vein on its anterior medial surface just inferior to the inguinal ligament through an anterior aperture in the fascia lata. The femoral artery gives rise to several branches near its posterior lateral surface near the center of the femoral triangle: slightly superiorly the deep femoral artery and slightly inferiorly the medial and lateral circumflex arteries; there is a well-known anatomical variation.[3]

The superficial epigastric artery emerges from the femoral artery near the proximal portion of the femoral triangle; it provides blood supply to the skin overlying the femoral triangle as well as the skin of the lower abdomen.[4] The external pudendal artery and the superficial iliac circumflex artery can also supply blood to the skin overlying the femoral triangle.[4]

Lymphatics are the most medial major structures contained within the femoral triangle. The deep inguinal lymph nodes are positioned within the femoral triangle and are separated from the superficial inguinal nodes by the fascia lata. The deep inguinal nodes receive drainage from the glans, clitoris, deep leg structures, and superficial inguinal nodes.

The Cloquet node is located within the femoral triangle just inferior to the inguinal ligament and is the most superior inguinal node; it receives drainage from both the superficial and deep inguinal lymph nodes and can be removed to assess metastasis in cases of cancer within its region of drainage. The perineum, genitalia, abdomen below the umbilicus, lower anus, and lower back all drain to the superficial inguinal nodes.[5]

Nerves

The primary nerve contained within the femoral triangle is the femoral nerve, arising from L2, L3, and L4. The femoral nerve enters the femoral triangle inferior to the inguinal ligament, external to the femoral sheath, and is the most lateral of the significant structures contained within the triangle. The nerve is encased within the iliopsoas during its course through the femoral triangle. The femoral nerve has anterior and posterior divisions that arise near the level of the lateral circumflex artery; there are known anatomical variations of the branch point.[6]

The anterior division provides innervation to the sartorius and gives rise to the medial femoral cutaneous nerve. The posterior division innervates the quadriceps femoris muscles and gives rise to the saphenous nerve.[7] The genitofemoral nerve originates from L1 and L2 and provides innervation to the skin overlying the femoral triangle as well as the cremaster muscle and scrotal skin in males and the mons pubis and labia majora in females. The femoral branch of the genitofemoral nerve follows a course within the femoral sheath. It lies lateral and superficial to the femoral artery. The femoral branch of the genitofemoral nerve pierces the anterior layer of the sheath and fascia lata at the saphenous opening to innervate the skin and subcutaneous tissue above.

Muscles

The femoral triangle includes the inguinal ligament and the following muscles:

Adductor Longus - forms the medial border as well as a portion of the medial floor of the femoral triangle. Its origin is the superior ramus of the pubis, and its insertion is on the linea aspera of the femur.[8]

Sartorius - is the longest muscle in the body, and it makes the lateral border of the femoral triangle.[8] It originates at the anterior superior iliac spine and inserts into the pes anserinus.

Pectineus - forms a portion of the medial floor of the femoral triangle. It is a quadrangular muscle that originates from the pectinate line of the pubis and inserts on the pectinate line of the femur.[8]

Iliopsoas - forms the lateral floor of the triangle. Iliopsoas refers to the two muscles, iliacus, and psoas, that originate as separate muscles in the abdomen and join into one in the hip to serve as the most powerful flexor of the thigh at the hip.[8]

Physiologic Variants

The basic structure of the femoral triangle is highly conserved and could theoretically undergo alteration by the congenital absence of a muscle that composes one of its borders or rare anatomical malformation of its contents. The overall size of the femoral triangle can vary based on the size of the individual. Many of the structures that pass through the femoral triangle are critical to the viability of the limb and are also highly conserved.[9]

The branches of the femoral artery, such as the deep femoral artery and lateral circumflex arteries, display more anatomic variance in their origin, with most diverging from the artery posterior-laterally and some diverging posteriorly or posterior-medially.[3]

Surgical Considerations

Thorough knowledge of the anatomy of the femoral triangle and the structures contained within is critical before surgical intervention. The structures of the femoral triangle are of high importance to the health of the limb and could potentially suffer damage during femoral hernia repairs, nerve blocks, or other surgical procedures in the area. The femoral triangle is also an important area for lymphatic drainage and can be evaluated to assess for primary or metastatic cancer in the superficial and deep inguinal lymph nodes.[10]

Clinical Significance

The femoral triangle is an important location for many reasons: it provides palpable access to the vital femoral artery, is a common location for quick vascular access, and can be used to locate many important structures for interventions. Radiologic interventions such as coronary and peripheral angioplasty, interventional embolization, and many other interventional endovascular procedures obtain catheterization through the femoral artery or vein to gain access to the many significant vessels of the body.[11]

The large diameter of the vessels within the femoral triangle allows the introduction of larger catheters. Venipuncture of the femoral vein in the femoral triangle can be used for venous access when peripheral veins cannot be accessed. The femoral triangle can be easily visualized with ultrasound, and many of the procedures that require access to the femoral vessels can be initiated under ultrasound guidance. The area of the femoral triangle and its roof contain both deep and superficial inguinal lymph nodes; this area can be a target for lymphadenectomy in the staging of cancer involving the inguinal lymphatic drainage.[12]

Lériche Syndrome

Lériche syndrome is a triad of erectile dysfunction, claudication, and diminished distal arterial pulses.[13][14][13] The symptoms of this syndrome are bilateral claudication, erectile dysfunction, absence of femoral arterial pulses, lower extremity pallor, and leg pain. Risk factors for developing the syndrome include diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cigarette smoking, and hyperlipidemia.[15][16] Lériche syndrome has also manifested as retinal occlusions.[17] It has been misdiagnosed as complex regional pain syndrome.[17]

The ankle-brachial index is a useful and non-invasive technique to assist in determining the presence of peripheral arterial disease, which is one of the underlying factors in Lériche syndrome. This technique involves measuring the blood pressure at the ankle and then at the antecubital fossa. A low number is an indicator of peripheral arterial disease. This result points toward a diagnosis of Lériche syndrome. The diagnosis can be confirmed using Doppler ultrasonography, computer tomographic angiography, and aortic angiography.

The differential diagnosis of Lériche syndrome includes aortic occlusion, neuropathy, aortic dissection, spinal cord stenosis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, and spinal disc herniation.[16][18][19]

Treatment of Lériche Syndrome can involve aortoiliac endarterectomy, aortofemoral bypass grafting, and endovascular bypass.[20][21][22][23]

Erectile Dysfunction

Fifty years ago, erectile dysfunction was considered primarily a psychological problem.[24] It is now known that erectile dysfunction can result from various organic causes, including pituitary tumors, chronic alcohol misuse, vascular causes (such as Lériche’s syndrome), neurogenic causes, Peyronie disease, hormonal malfunctions, and the side effects of various medications.[24]

Although erectile dysfunction can have severe psychological effects, it is not fatal per se. However, the subset of the population of patients with erectile dysfunction that have Lériche syndrome will succumb unless treatment is instituted. Thus prompt diagnosis and treatment of Lériche syndrome are essential to avoid disastrous future outcomes.

Other Issues

Many different pathologic processes can exist within the femoral triangle. Femoral hernias can emerge below the inguinal ligament and bulge directly into the femoral triangle. Peripheral arterial disease can develop within the femoral artery as it passes through the triangle. Deep venous thrombosis can develop in the femoral vein. Hematomas or arterio-venous fistulas can develop in the femoral triangle after vascular intervention. Whether primary or metastatic, cancer within the superficial or deep inguinal lymph nodes can lead to lymphadenopathy.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Femoral Triangle Structures. This anterior view shows the femoral artery, vein and nerve, and the deep external pudendal vessels, superficial external pudendal vessels, superficial epigastric vessels, and superficial iliac circumflex nerve.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Mahabadi N, Lew V, Kang M. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Femoral Sheath. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29494010]

Sheeba CJ, Andrade RP, Palmeirim I. Getting a handle on embryo limb development: Molecular interactions driving limb outgrowth and patterning. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. 2016 Jan:49():92-101. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.01.007. Epub 2015 Jan 21 [PubMed PMID: 25617599]

Nasr AY, Badawoud MH, Al-Hayani AA, Hussein AM. Origin of profunda femoris artery and its circumflex femoral branches: anatomical variations and clinical significance. Folia morphologica. 2014 Feb:73(1):58-67. doi: 10.5603/FM.2014.0008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24590524]

Tremblay C, Grabs D, Bourgouin D, Bronchti G. Cutaneous vascularization of the femoral triangle in respect to groin incisions. Journal of vascular surgery. 2016 Sep:64(3):757-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.04.385. Epub 2015 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 26727692]

Rao AS, Rajmanickam K, Narayanan GS. Study of distribution of inguinal nodes around the femoral vessels and contouring of inguinal nodes. Journal of cancer research and therapeutics. 2015 Jul-Sep:11(3):575-9. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.163735. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26458584]

Lonchena TK, McFadden K, Orebaugh SL. Correlation of ultrasound appearance, gross anatomy, and histology of the femoral nerve at the femoral triangle. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2016 Jan:38(1):115-22. doi: 10.1007/s00276-015-1465-0. Epub 2015 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 25821034]

Glenesk NL, Lopez PP. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Thigh Nerves. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29489256]

Launico MV, Sinkler MA, Nallamothu SV. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Femoral Muscles. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763184]

Pakhiddey R, Pangtey B, Mehta V, Suri RK. Unilateral atypical disposition of femoral vessels: clinico- embryological annotations. La Clinica terapeutica. 2014:165(3):147-9. doi: 10.7417/CT.2014.1713. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24999568]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYao K, Zou ZJ, Li ZS, Zhou FJ, Qin ZK, Liu ZW, Li YH, Han H. Fascia lata preservation during inguinal lymphadenectomy for penile cancer: rationale and outcome. Urology. 2013 Sep:82(3):642-7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.05.021. Epub 2013 Jul 19 [PubMed PMID: 23876593]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceUhlmann ME, Walter C, Taher F, Plimon M, Falkensammer J, Assadian A. Successful percutaneous access for endovascular aneurysm repair is significantly cheaper than femoral cutdown in a prospective randomized trial. Journal of vascular surgery. 2018 Aug:68(2):384-391. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.12.052. Epub 2018 Mar 8 [PubMed PMID: 29526378]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMicheletti L, Bogliatto F, Massobrio M. Groin lymphadenectomy with preservation of femoral fascia: total inguinofemoral node dissection for treatment of vulvar carcinoma. World journal of surgery. 2005 Oct:29(10):1268-76 [PubMed PMID: 16136289]

Ellis H. René Leriche: the Leriche syndrome. Journal of perioperative practice. 2013 Jun:23(6):147-8 [PubMed PMID: 23909169]

Tkocz M, Brzęk A, Marcinek M, Skrzypulec-Plinta V, Ziaja D. Pre and Postoperative Sexual Dysfunction in Patients with Leriche Syndrome-A Prospective Pilot Study. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2022 Mar 6:19(5):. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19053091. Epub 2022 Mar 6 [PubMed PMID: 35270783]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMatsuura H, Honda H. Leriche syndrome. Cleveland Clinic journal of medicine. 2021 Sep 1:88(9):482-483. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.88a.20179. Epub 2021 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 34470750]

Frederick M, Newman J, Kohlwes J. Leriche syndrome. Journal of general internal medicine. 2010 Oct:25(10):1102-4. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1412-z. Epub 2010 Jun 22 [PubMed PMID: 20568019]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDubey D, Ramanjulu R, Shanmugam MP, Mishra DK. Acquired conjunctival sessile hemangioma. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2020 Jun:68(6):1155-1156. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1978_19. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32461454]

Turner GR. The Leriche syndrome: aortoiliac occlusive disease. Journal of the Tennessee Medical Association. 1968 Dec:61(12):1191-5 [PubMed PMID: 4883348]

Finsterer J, Stöllberger C, Mölzer G, Fischer H. A vascular cause of painful lumbar transverse syndrome. The journal of spinal cord medicine. 2009:32(5):587-90 [PubMed PMID: 20025157]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSetacci C, Galzerano G, Setacci F, De Donato G, Sirignano P, Kamargianni V, Cannizzaro A, Cappelli A. Endovascular approach to Leriche syndrome. The Journal of cardiovascular surgery. 2012 Jun:53(3):301-6 [PubMed PMID: 22695262]

Lee WJ, Cheng YZ, Lin HJ. Leriche syndrome. International journal of emergency medicine. 2008 Sep:1(3):223. doi: 10.1007/s12245-008-0039-x. Epub 2008 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 19384523]

Liang HL, Li MF, Hsiao CC, Wu CJ, Wu TH. Endovascular management of aorto-iliac occlusive disease (Leriche syndrome). Journal of the Formosan Medical Association = Taiwan yi zhi. 2021 Jul:120(7):1485-1492. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2020.10.033. Epub 2020 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 33189506]

Beyaz MO, Urfalı S, Kaya S, Oruç D, Fansa İ. Is Surgery the Only Fate of the Patient with Leriche Syndrome? Our Endovascular Therapy Results Early Follow-Up Outcomes. The heart surgery forum. 2022 Oct 12:25(5):E721-E725. doi: 10.1532/hsf.4691. Epub 2022 Oct 12 [PubMed PMID: 36317918]

Ludwig W, Phillips M. Organic causes of erectile dysfunction in men under 40. Urologia internationalis. 2014:92(1):1-6. doi: 10.1159/000354931. Epub 2013 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 24281298]