Introduction

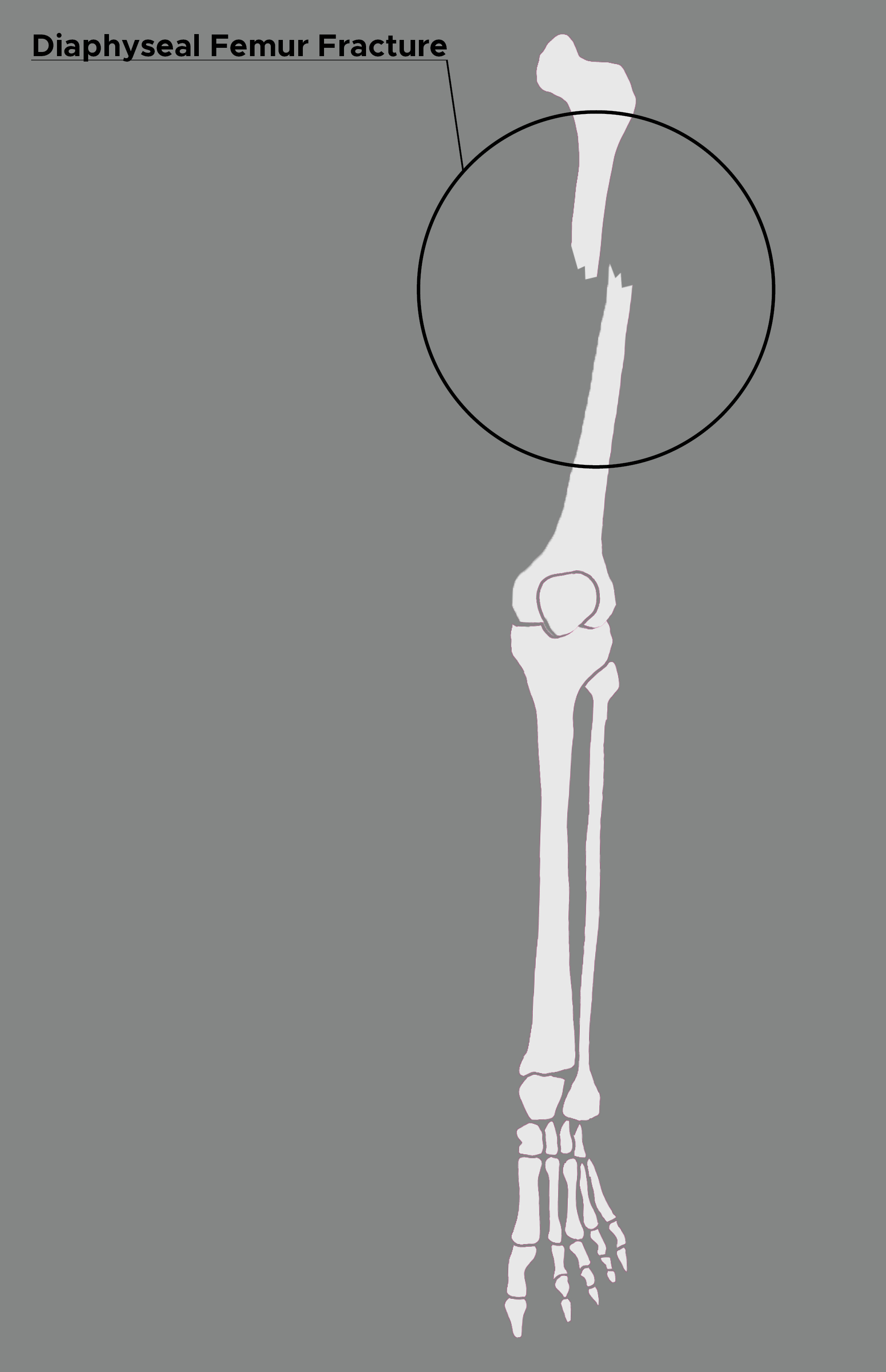

Diaphyseal femur fractures are commonly encountered in association with other high-energy injuries (see Image. Diaphyseal Femur Fracture). These injuries can lead to life-threatening sequelae. Prompt intervention and thoughtful management lead to the best patient outcomes. Unlike in the past when these fractures were managed with only splints, today intramedullary (IM) nailing is the mainstay of treatment. Pediatric patients are managed with flexible rods to allow for bone growth.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The femur is divided into the following regions: head, neck, intertrochanteric, subtrochanteric, shaft, supracondylar, and condylar areas.

Younger patients are generally involved in high-energy mechanisms, most commonly motor vehicle collisions. Elderly patients can sustain osteoporotic femur fractures from ground-level falls.[1] Another common etiology is from gunshot injuries sustained to the lower extremity.

Stress fractures can occur in individuals with excess physical activity. Finally, some low energy femur fractures may be associated with osteoporosis or prolonged use of bisphosphonates.

Epidemiology

There are an estimated 9 to 22 femur fractures per 1000 people worldwide that present every year. These injuries present in a bimodal distribution. Studies show that diaphyseal fractures are often seen older patients, those with decreased bone density, low body mass index, and extensive anterior and lateral bowing.

Pathophysiology

The femur is the largest bone in the human body. It has an anterior bow with a radius of curvature of 120 cm.[2] Along the posterior middle third of the diaphysis, there is a raised crest known at the linea aspira, which serves as the attachment site for muscles and fascia and a strut to compensate for the anterior bow.

The characteristic deformity following a femur fracture is caused by the strong lower extremity muscles which are attached to the femur. The proximal fragment is held in flexion and abduction. The iliopsoas, which attaches at the lesser trochanter, provides a strong flexion vector. The gluteus medius and minimus, which attach at the greater trochanter, provide a strong abduction force. The distal fragment is held in varus and extension. The adductors attach at the medial femoral condyle and provide a varus force. The gastrocnemius attaches at the posterior distal femur, pulling the fragment posteriorly and inferiorly and creating an extension deformity at the fracture.

History and Physical

As there may be concurrent life-threatening injuries, it is important to assess the patient’s entire status. Upon presentation to the trauma bay, adherence to the advanced trauma life support (ATLS) principles is paramount. If the patient is unstable or if intra-abdominal pathology is suspected, the patient may be transported to the operating room urgently for exploratory laparotomy. It is important to remember that the patient’s life precedes limb.

If the patient is stable, it is important to perform a thorough physical exam. An obvious thigh deformity may be noted. It is important to perform a thorough neurovascular exam including pulses and assess for an open fracture.

Bilateral femur fractures have been associated with a greater risk of pulmonary complications and increased mortality.

Evaluation

Imaging

Imaging starts with plain radiographs. Orthogonal radiographs of the femur should be obtained. In addition, orthogonal images should be obtained of the hip and knee joints.

It is important to assess for ipsilateral femoral neck injuries. A 1-9% incidence has been noted in the literature. Many level one trauma centers have adopted protocols to include computed tomography (CT) scans which include both femurs to the level of the lesser trochanter. Before the widespread adoption of these protocols, associated ipsilateral femoral neck injuries were missed approximately 20-50% of the time.[3]

Imaging may also play a part in management decision-making. The start site for IM nailing may be compromised in diaphyseal fractures with an associated proximal femur fracture. In these cases, a CT of the proximal femur is helpful to assess the integrity of the greater trochanter or piriformis fossa.

Classification

Open femur fractures can be categorized by the Gustillo-Anderson classification system. Epidemiologic studies documented 43% grade I, 31% grade II and 26% grade III open fractures. Aggressive management is necessary due to the mechanism of injury and the amount of soft tissue that must be violated for a femur fracture to become open.

Two common classification systems are used to describe diaphyseal femur fractures.

The Orthopaedic Trauma Association Classification

32A - Simple

- A1 - Spiral

- A2 - Oblique, an angle less than 30 degrees

- A3 - Oblique, an angle less than 30 degrees

32B - Wedge

- B1 - Spiral wedge

- B2 - Bending Wedge

- B3 - Fragmented Wedge

32C - Complex

- C1 - Spiral

- C2 - Segmental

- C3 - Irregular

Winquist and Hansen Classification[4]

- Type 0 No comminution

- Type I Insignificant comminution

- Type II greater than 50% cortical contact

- Type III less than 50% cortical contact

- Type IV Segmental, with no contact between proximal and distal fragment

Blood work is always done to assess levels of hemoglobin. A significant amount of blood loss can occur with a femur fracture, which can lead to hypotension. If the wound is open, cultures should be obtained.

Treatment / Management

Open Fractures

In instances of an open fracture, prompt antibiotics should be given in accordance with the facility’s protocol. Weight-based cefazolin is commonly used. Bedside irrigation and debridement should be performed. Operative irrigation and debridement should ideally be performed within 2 hours of presentation.

Ipsilateral Femoral Neck Fractures

In the rare setting of a femoral shaft fracture with an ipsilateral femur fracture, it is recommended that the femoral neck fracture takes fixation precedence. [5] Authors recommend an anatomic reduction of the femoral neck first to decrease the risk of non-union and avascular necrosis (AVN) of the femoral head. After femoral neck fixation, the femoral shaft fracture is then addressed.

End of Bed Skeletal Traction

Traction provides the patient with pain control and assists the surgeon with maintaining anatomic length. The strong thigh muscles immediately contract upon injury, causing shortening of the femur. After radiographic assessment of the knee joint, a traction pin may be placed in the distal femur or the proximal tibia under local anesthesia. For femoral traction, a 4 mm Steinman pin is inserted two fingerbreadths above the superior border of the patella to ensure that it is extra-articular. It is placed in the anterior third of the femur to allow passage of the nail in the event sterile traction is required intra-operatively. For tibial traction, the pin is inserted three fingerbreadths distal to the superior aspect of the tibial tubercle. Some have argued against tibial traction due to ligamentous strain and the reported incidence of concurrent ligamentous injury with diaphyseal femur fractures.[6] Most often, the pin is simply placed to avoid the zone of injury. Twelve pounds (five kilograms) of traction is applied in a longitudinal fashion and can be adjusted based on the patient’s weight and muscular tone. Relief is noted by the patient after the thigh muscle fatigue.(B2)

External Fixation

External fixation may be required in the setting of damage control orthopedics.[7] If the patient is hemodynamically unstable and is taken to the operating room for another procedure, it may be prudent to proceed with external fixation. External stabilization also may be indicated in the setting of vascular repair. Schanz pins are inserted proximally and distally to the fracture and traction is applied to approximate length, alignment, and rotation. Some constructs may require the surgeon to span the knee. Studies have shown an approximate 10% infection rate of external fixator pins.[8] Patients with multiple injuries are transitioned to definitive fixation when stable.(B2)

Intramedullary Nailing

IM nailing is the mainstay of treatment for diaphyseal femur fractures. Nailing provides relative stability at the fracture and the femur heals through secondary bone healing.

Fracture fixation with IM nailing can be achieved through an antegrade or retrograde fashion. Retrograde nailing utilizes a start point in the center of the intercondylar notch of the distal femur. Antegrade IM nailing uses 2 distinct start points, greater trochanter, and piriformis fossa starting points. Trochanteric and piriformis entry nails have been studied extensively, with the general consensus of equivalent outcomes.[9] The advantage of using the piriformis entry point is its colinear orientation with the long axis of the femur. This reduces the risk of varus malalignment. The disadvantages of this starting point are the technical skill needed to establish this point, especially in obese patients. [10] This entry point puts the piriformis muscle insertion at risk of iatrogenic injury resulting in an abductor limp. There is also an increased risk of AVN of the femoral head in pediatric patients. The greater trochanter entry point offers the advantage of reduced risk of injury to adductors, it is less technically demanding and is a more appropriate option for obese patients. The disadvantage to the greater trochanter entry point is that it is not colinear with the axis of the femur. This mismatch necessitates the use of an IM nail that is specifically designed for this entry point, in order to avoid varus malalignment. [10](B2)

In regard to nail design, the radius of curvature of the IM nail must match the radius of curvature of the patient's femur. [2] An IM nail with a radius of curvature greater than that of the patient's femur (i.e. a straighter nail), can cause perforation of the anterior cortex of the femur during insertion.

Patients may generally be made weight-bearing as tolerated following IM nailing.

Submuscular Plating

Submuscular plating is generally relegated to complex or peri-prosthetic fractures in which the start site is compromised or not available due to a separate implant. A lateral plate can be applied through a vastus splitting or sub-vastus approach. Weight-bearing is generally protected after plating.

Timing of Surgery

It is recommended that femur fractures be managed within 2-12 hours after injury, provided that the patient is hemodynamically stable. Studies show significant benefits when intervention is undertaken within the first 24 hours. Immediate fixation lowers pulmonary complications, decreases mortality, and avoids long ICU stays. However, the type of fixation remains debatable

Differential Diagnosis

Patients with a femoral shaft fracture, an ipsilateral femoral neck fracture must be ruled out. Depending on the mechanism of injury patients may have a variety of concomitant injuries. In a high energy scenario, compartment syndrome must be ruled out. Patients with a low energy mechanism, the fracture may be caused by a pathologic process due to neoplasm or metabolic derangement, in which case a thorough workup is warranted.

Prognosis

The prognosis of patients with diaphyseal femur fracture varies on age, comorbidity, presence of osteoporosis, and type of treatment. IM nailing has good results, but a significant number of patients require removal of hardware in the future because of pain. Deaths after surgery in elderly patients are not uncommon. Other complications include infection, blood loss, nonunion, delayed union, malunion, and need for repeat surgery. External fixation is effective but is also associated with pin infections and angulation problems. Patients also need prolonged stay in the hospital, followed by extensive rehabilitation. Gait problems and pain continue to be present in a significant number of patients.

Complications

Non-unions are rare but do occur.[11] In these instances, the root of the non-union must be established. Revision surgery can be pursued when a specific aspect of fixation, such as stability or biology, is to be addressed. Hypertrophic, aseptic non-unions can be addressed with compression and exchange nailing.[12] In atrophic non-unions, infection must be ruled out, especially in the setting of previously open fractures. The patient’s nutrition status must be assessed with labs. Revision of atrophic non-union is often supplemented with bone grafting.

Deaths related to deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism, infection, nerve injury, and compartment syndrome are not uncommon.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients who sustained femoral shaft fractures require close follow-up to monitor fracture healing. Insufficiency fractures of the femoral shaft are uncommon, however, prevention of these fragility fractures can be mitigated through appropriate screening and medical management for those at risk, i.e. elderly, or vitamin D deficient individuals.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with diaphyseal femur fractures are usually managed by an interprofessional team that includes an orthopedic surgeon, trauma surgeon, emergency department physician, physical therapist, nurse practitioner, radiologist, and an intensivist. These fractures are usually caused by high impact energy and may be associated with other injuries. The patient with a femur fracture can develop significant bleeding and may require blood transfusions. The decision for the type of treatment depends on the type of injury and patient stability. After treatment, most patients need prolonged rehabilitation to regain muscle strength and function. For isolated injuries of the femur, the prognosis is good but pain and gait difficulty may be residual problems.[13][14]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Singer BR, McLauchlan GJ, Robinson CM, Christie J. Epidemiology of fractures in 15,000 adults: the influence of age and gender. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 1998 Mar:80(2):243-8 [PubMed PMID: 9546453]

Egol KA, Chang EY, Cvitkovic J, Kummer FJ, Koval KJ. Mismatch of current intramedullary nails with the anterior bow of the femur. Journal of orthopaedic trauma. 2004 Aug:18(7):410-5 [PubMed PMID: 15289685]

Tornetta P 3rd, Kain MS, Creevy WR. Diagnosis of femoral neck fractures in patients with a femoral shaft fracture. Improvement with a standard protocol. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2007 Jan:89(1):39-43 [PubMed PMID: 17200308]

Winquist RA, Hansen ST Jr, Clawson DK. Closed intramedullary nailing of femoral fractures. A report of five hundred and twenty cases. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1984 Apr:66(4):529-39 [PubMed PMID: 6707031]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePeljovich AE, Patterson BM. Ipsilateral femoral neck and shaft fractures. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 1998 Mar-Apr:6(2):106-13 [PubMed PMID: 9682073]

Walker DM, Kennedy JC. Occult knee ligament injuries associated with femoral shaft fractures. The American journal of sports medicine. 1980 May-Jun:8(3):172-4 [PubMed PMID: 7377448]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNowotarski PJ, Turen CH, Brumback RJ, Scarboro JM. Conversion of external fixation to intramedullary nailing for fractures of the shaft of the femur in multiply injured patients. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2000 Jun:82(6):781-8 [PubMed PMID: 10859097]

Parameswaran AD, Roberts CS, Seligson D, Voor M. Pin tract infection with contemporary external fixation: how much of a problem? Journal of orthopaedic trauma. 2003 Aug:17(7):503-7 [PubMed PMID: 12902788]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRicci WM, Schwappach J, Tucker M, Coupe K, Brandt A, Sanders R, Leighton R. Trochanteric versus piriformis entry portal for the treatment of femoral shaft fractures. Journal of orthopaedic trauma. 2006 Nov-Dec:20(10):663-7 [PubMed PMID: 17106375]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRicci WM, Gallagher B, Haidukewych GJ. Intramedullary nailing of femoral shaft fractures: current concepts. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2009 May:17(5):296-305 [PubMed PMID: 19411641]

Nonunion of the femoral diaphysis. The influence of reaming and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs., Giannoudis PV,MacDonald DA,Matthews SJ,Smith RM,Furlong AJ,De Boer P,, The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume, 2000 Jul [PubMed PMID: 10963160]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBrinker MR, O'Connor DP. Exchange nailing of ununited fractures. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2007 Jan:89(1):177-88 [PubMed PMID: 17200326]

Ibrahim JM, Conway D, Haonga BT, Eliezer EN, Morshed S, Shearer DW. Predictors of lower health-related quality of life after operative repair of diaphyseal femur fractures in a low-resource setting. Injury. 2018 Jul:49(7):1330-1335. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2018.05.021. Epub 2018 May 23 [PubMed PMID: 29866624]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKoso RE, Terhoeve C, Steen RG, Zura R. Healing, nonunion, and re-operation after internal fixation of diaphyseal and distal femoral fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International orthopaedics. 2018 Nov:42(11):2675-2683. doi: 10.1007/s00264-018-3864-4. Epub 2018 Mar 8 [PubMed PMID: 29516238]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence