Introduction

Fibrosarcomas are defined as malignant neoplasms composed of fibroblasts that may have varying amounts of collagen production and a "herringbone" architecture. Depending upon the origin, there are 2 main categories of fibrosarcomas: bone and soft tissue tumors. Adult fibrosarcomas have displayed a declining incidence over the past several decades as the classification of fibrosarcoma continually narrows, and other mesenchymal and non-mesenchymal tumors that mimic fibrosarcomas are more accurately diagnosed.[1][2] Fibrosarcomas can be subdivided into 2 types: infantile or congenital fibrosarcomas and adult-type fibrosarcomas. Infantile fibrosarcomas rarely metastasize, while adult-type fibrosarcomas are highly malignant.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Fibrosarcomas typically originate from fascia and tendons of soft tissue but can also occur in bones as a primary or secondary tumor within the medullary canal or the periosteum. Prior bone damage, whether from trauma or radiotherapy, may give rise to fibrosarcomas of the bone.[3][4]

Epidemiology

Adult fibrosarcoma is most common in middle-aged and older adults and rarely occurs in children. Male patients have a slight predominance, most commonly involving the deep soft tissues of the extremities, trunk, head, and neck.[2][5]

In a survey of adult fibrosarcomas, 80% were classified as "high-grade" (Grade 2 or 3), with 25% of the remaining low-grade lesions progressing to high-grade sarcoma locally over time. Fewer than 5% of all primary bone tumors and only 10% of musculoskeletal sarcomas are fibrosarcomas. Men are somewhat more likely than women to have bone fibrosarcoma. There is no known racial preference. The bony fibrosarcoma of the femur and tibia are the most common sites for lesions, followed by the humerus. These pathological lesions are typically metaphyseal in origin and appear from the second to the seventh decade of life.[6][7]

Pathophysiology

Fibrosarcomas derive from a mesenchymal cell origin, composed of spindle-cell fibroblasts with uncontrolled proliferation. Most frequently, fibrosarcomas originate from tendons and fascias of deep tissues but may also occur within the medullary canal or the periosteum of bones. Preexisting bone lesions such as bone infarcts, chronic osteomyelitis, Paget disease, and irradiated tissues may also give rise to secondary fibrosarcomas of the bone.[3]

Histopathology

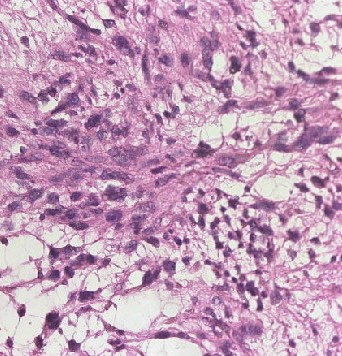

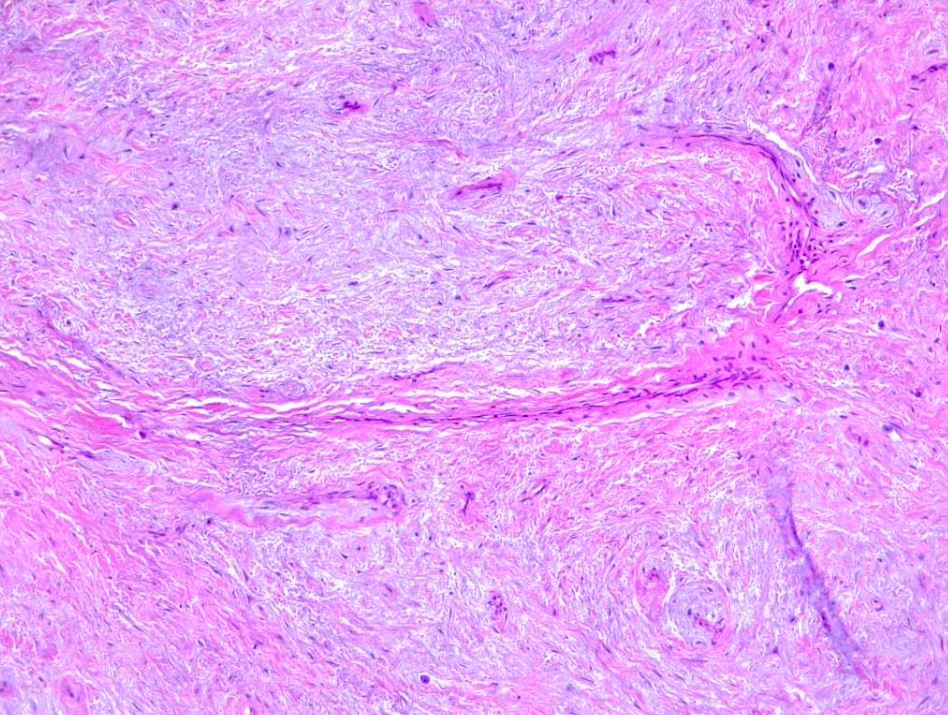

Fibrosarcomas are soft tissue sarcoma spindle cells characterized by fusiform oval nuclei, lance-shaped tapered cells, and unipolar or bipolar cytoplasm. Adult fibrosarcomas show a mild to moderate degree of pleomorphism. Neoplastic cells are arranged in long sweeping fascicles that form a classic "herringbone" pattern. Note that a high degree of pleomorphism should classify any tumor as an undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. Fibrosarcomas display varying degrees of mitotic activity and have darkly staining nuclei with prominent nucleoli and scant cytoplasm (see Images. Soft Tissue Fibrosarcoma).

A variable amount of stromal collagen is present within a fibrosarcoma, which may mimic fibromatosis in some tumors. Atypical spindle cells, the herringbone pattern, and varying amounts of collagen formation are all histological characteristics of bony fibrosarcoma.

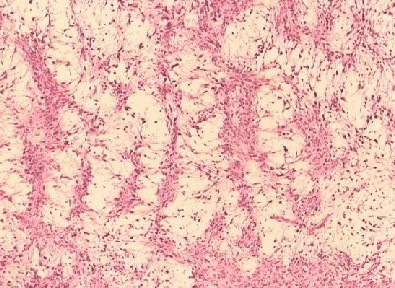

Myxofibrosarcoma encompasses a spectrum of malignant fibroblastic tumors featuring myxoid stroma, varying degrees of pleomorphism, and distinctive curvilinear vasculature. It is characterized by its low-grade nature, exhibiting both fibrous and myxoid regions, a whorled growth pattern, low cellularity, unremarkable fibroblastic cells, and the presence of curvilinear or arcuate vessels (see Image. Myxofibrosarcoma).

While histopathology is insufficient to distinguish fibrosarcomas from other spindle-cell sarcomas, appropriate immunohistochemistry can greatly assist in diagnosis by identifying characteristic tumor markers. Furthermore, measuring these markers on the cell surface or within the tumor environment is often critical in monitoring treatment efficacy and tumor recurrence.[8]

Vimentin is a marker indicative of a mesenchymal cell origin and is often the only positively stained marker in the diagnosis of fibrosarcomas. One might also find alpha-smooth muscle actin, muscle-specific actin, and desmin to be common myogenic markers, often representing myofibroblastic differentiation. In contrast, a positive S-100 protein marker would indicate a nerve sheath tumor, while CD31, CD34, and Factor VIII non-von Willebrand factor would suggest a vascular tumor rather than a true fibrosarcoma.[3][5][9]

History and Physical

Clinicians should inquire about the location, size, shape, and consistency of any soft tissue masses. Furthermore, clinicians should inquire about any local scar tissue, especially due to prior burn injuries. Similarly, prior vascular grafts, joint prosthetics, or other surgically implanted foreign materials should be noted. Previously irradiated tissue may be a risk factor for the development of fibrosarcoma, as are preexisting dermatofibrosarcoma or well-differentiated liposarcoma.[3][10]

Additionally, the regional lymph node examination should accompany a complete neurovascular examination. Fibrosarcomas typically arise in deep connective tissue rich with collagen; thus, it is less common in the retroperitoneum, mediastinum, head, and neck. Fibrosarcomas generally are spherical with sharp demarcation from surrounding tissue and have a firm consistency on palpation. Fibrosarcoma tumors typically range from 3 cm to 8 cm in size.[3][11]

Fibrous tumors often have a very delayed diagnosis, as they arise from deep tissue and cause painless soft-tissue swelling. It is usually not until symptoms arise from the local mass effect of a deep tumor that the lesion is identified and diagnosed. Impeded blood circulation, nerve compressions, or movement restriction are often present when diagnosing a fibrosarcoma.[3] Late presentations of fibrosarcomas may be accompanied by weight loss and anorexia. Furthermore, pain associated with a deep soft tissue mass greater than 5 cm in size increases suspicion of malignancy and warrants referral for further specialist evaluation.[3]

The most frequent presentation of bony fibrosarcoma is chronic dull pain with or without soft tissue swelling. Patients with tumors around joints usually present with a limited and painful range of motion.[12]

Evaluation

Radiographic imaging is the first diagnostic step when history and physical examination suggest a diagnosis of a malignant soft tissue tumor. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred procedure to evaluate tumors of the extremities or pelvis and will provide information about a tumor's size, margins, signal density, degree of necrosis, and vascularization. CT scans may also be employed to assess for tumors of the retroperitoneum or to identify any possible bony involvement. Fibrosarcomas appear as localized, nonspecific ovoid lesions with slightly irregular margins. The displacement of surrounding tissue will be demonstrated.[3]

If imaging suggests the presence of a soft tissue malignancy, a core needle biopsy is warranted, as a fine needle aspiration (FNA) has been criticized as unsatisfactory for making an accurate initial diagnosis. However, FNA has utility in monitoring progression and identifying tumor recurrence or metastasis if previous cytological studies are available for comparison. Finally, more invasive surgical biopsies may be warranted in tumors where minimally invasive biopsy techniques have failed or are untenable. Excisional biopsy is generally recommended when you suspect a soft tissue sarcoma of 3 cm to 5 cm in size, whereas partial incisional biopsies are appropriate when tumor size exceeds 5 cm.[3][11][13]

A fibrosarcoma's radiological appearance is comparable to an osteoid osteogenic sarcoma. Fibrosarcoma of bone usually appears irregular in shape and is osteolytic in nature. The periosteal reaction is minimal, however, the lesion has a moth-eaten appearance. These sarcomas are intramedullary and typically metaphyseal but can extend to the diaphysis. Technetium-99m bone scanning reveals a hot spot around the pathological area. MRI may be the most appropriate modality for determining the lesion size, neurovascular involvement, and extraosseous extent of fibrosarcoma.[14]

Treatment / Management

Surgical excision is the mainstay of treatment for localized soft tissue sarcomas. Intramuscular tumors should have a compartmental en-bloc excision, and in this scenario, no additional radiation therapy would be indicated. If there is extra-compartmental growth, or if the tumor does not reach the origin or insertion of the muscle, a wide-surgical resection would be appropriate to obtain tumor-free margins. Two centimeters of margin is generally recommended; however, no definitive evidence exists for the best safety margin. Surrounding structures such as nerves and vascular structures must always be considered.[15](B3)

For tumors that are high-grade and larger than 5 cm, adjuvant radiation therapy is highly recommended. If clear margins are not obtained, reoperation is the most appropriate next step in management.

The utility of chemotherapy in managing soft tissue sarcomas is unclear and, therefore, not generally recommended in standard treatment. Additionally, fibrosarcomas tend to form a co-resistance to drugs such as vincristine, vinblastine, and etoposide after using the first-line agent doxorubicin. Therefore, only patients with high-stage fibrosarcomas that require chemotherapy should be treated with anthracyclines as the first-line treatment. The addition of actinomycin D and ifosfamide may increase the response to treatment. That being said, an improvement in survival has only been demonstrated in 4 to 11% of sarcoma patients treated with standard chemotherapy. Similarly, fibrosarcoma of bone is treated with multiagent chemotherapy with wide resection. These tumors have a high rate of recurrence. [12]

Finally, intratumoral injections of matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors such as TIMP-1-GPl fusion protein have been shown to lead to a decreased tumor mass and growth. Furthermore, injection shows inhibition of cell migration and increased tumor cell apoptosis.[3][16](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of fibrosarcoma is a diagnosis of exclusion. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcomas, sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcomas, fibrosarcomatous dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and synovial sarcomas are all clinically distinct diagnoses that may be mistaken for a true adult fibrosarcoma.

While storiform areas may be present on histology in association with adult fibrosarcomas, storiform growth suggests the tumor arose from dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Furthermore, CD34-positive tumors likely represent fibrosarcomas arising from dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans or a fibrosarcoma progression from a single malignant fibrous tumor.

It is unlikely to find a fibrosarcoma within visceral organs, and these tumors likely represent cytokeratin-negative carcinomas. In the retroperitoneum, initially reported fibrosarcoma-like lesions frequently prove to be dedifferentiated liposarcomas.[2][5]

Medical Oncology

Adult fibrosarcoma is a very aggressive subtype of soft tissue sarcomas with a recurrence rate of approximately 50%. Fibrosarcomas tend to respond poorly to chemotherapy, which may be attributed to their intrinsic resistance to chemotherapeutic agents.[17]

There is limited data regarding histology-driven treatment for various subtypes of soft tissue sarcoma. The benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in fibrosarcoma is debatable. Neoadjuvant treatment with the MAID protocol, an integrated chemoradiation program, has shown benefits in high-grade soft tissue sarcomas, including fibrosarcomas, with a lower rate of recurrence and metastasis and an improvement in survival.[18][19][20]

In advanced or unresectable tumors, doxorubicin is the most commonly used chemotherapeutic agent and is usually considered the first-line drug, with response rates ranging between 18% to 25%. There is no specific second-line therapy; however, some chemotherapeutic agents have shown benefit, including ifosfamide, with a response rate of around 25% in pretreated soft tissue sarcomas, including liposarcomas.[21][22]

The combination of gemcitabine and docetaxel has shown a response rate of 16.7% with an acceptable toxicity profile. Huiwen Ma et al reported a response rate of 25%, a disease control rate of 82%, and better tolerance with Apatinib, a VEGFR 2 inhibitor, compared to standard second-line chemotherapy.[23][24]

There is emerging data regarding the efficacy of immunotherapy in soft tissue sarcomas. Combining chemotherapy with pembrolizumab has shown some promising results in phase 1/2 nonrandomized clinical trials. Further studies are warranted to explore its benefits in patients with soft tissue sarcomas, including fibrosarcomas.[25][26]

Staging

Netherlands Committee on Bone Tumours (1966) [27]

- Grade 1- Well-differentiated tumor

- Grade 2- Moderately differentiated tumor

- Grade 3- Poorly differentiated tumor

Prognosis

As discussed above, 80% of adult fibrosarcomas are determined to be high-grade (Grades 2 or 3). Furthermore, 25% of the remaining low-grade lesions progress to a local recurrence of high-grade fibrosarcoma. These tumors are aggressive, with many local recurrences as well as lymph and parenchymal metastases. The survival of adult fibrosarcomas is <70% at 2 years and <55% at 5 years. In comparison to intraosseous fibrosarcoma, soft-tissue fibrosarcoma is regarded to have a better prognosis.[5][28][29]

Complications

As the mainstay of treatment for fibrosarcoma is surgical, complications are the same as any other surgery, including infection, bleeding, damage to surrounding tissues or structures, and even death. Adjuvant radiation therapy can further increase potential complications such as local fibrosis or increased risk of wound infection. In cases of high-stage fibrosarcomas, chemotherapy may be used. Each chemotherapy agent carries its own risk profile, but doxorubicin, the mainstay of treatment, is classically associated with an increased risk of dilated cardiomyopathy.[30]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Fibrosarcoma has a poor prognosis due to its aggressive disease course. All patients should undergo routine medical screenings and consult with their primary care physician regarding any soft tissue masses they may have noticed on self-examination.[3] To maximize outcomes, patients must seek medical treatment from trained specialists with expertise in musculoskeletal tumors.

Optimal outcomes are seen when there is complete surgical tumor resection with histologically tumor-free margins and appropriate adjuvant treatment to surgical intervention in order to maximize treatment benefit and minimize recurrence. The prevention of tumor invasion and metastasis is critical.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Enhancing patient-centered care and improving outcomes for fibrosarcoma necessitates a coordinated and multidisciplinary approach involving an interprofessional team, including physicians, advanced care practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and others. Each team member should possess specialized knowledge and skills in fibrosarcoma diagnosis, staging, treatment modalities, and management. Continuous education and skill development are essential.

As surgical excision is the mainstay of treatment for fibrosarcomas, a surgical team with experience in musculoskeletal oncology is essential to optimize patient outcomes while minimizing risks and complications of surgery. A pathologist is required to assist in making an accurate diagnosis of any sarcomatous lesion and help guide appropriate treatment. Effective pain management is crucial. Collaborate with pain specialists and pharmacists to optimize pain control while minimizing side effects. Most importantly, nurses and other medical staff must work with the patient to ensure a patient-centered approach to care that meets the patient's physical, psychological, and emotional needs.

Collaborative discussions should focus on evidence-based treatment strategies, including surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapies tailored to individual patient needs and preferences. Interprofessional team members should stay updated on the latest research and clinical trials related to fibrosarcoma to offer eligible patients access to innovative treatments. Patients and their families should receive comprehensive education about fibrosarcoma, treatment options, potential side effects, and self-care measures.

Optimizing patient care and team performance for fibrosarcoma requires a holistic and patient-centered approach. Healthcare professionals from various disciplines must collaborate, communicate effectively, and continually update their skills to provide the best possible care and improve outcomes for individuals affected by this challenging malignancy.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Jo VY, Fletcher CD. WHO classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the 2013 (4th) edition. Pathology. 2014 Feb:46(2):95-104. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0000000000000050. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24378391]

Folpe AL. Fibrosarcoma: a review and update. Histopathology. 2014 Jan:64(1):12-25. doi: 10.1111/his.12282. Epub 2013 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 24266941]

Augsburger D, Nelson PJ, Kalinski T, Udelnow A, Knösel T, Hofstetter M, Qin JW, Wang Y, Gupta AS, Bonifatius S, Li M, Bruns CJ, Zhao Y. Current diagnostics and treatment of fibrosarcoma -perspectives for future therapeutic targets and strategies. Oncotarget. 2017 Nov 28:8(61):104638-104653. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20136. Epub 2017 Aug 10 [PubMed PMID: 29262667]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAngiero F, Rizzuti T, Crippa R, Stefani M. Fibrosarcoma of the jaws: two cases of primary tumors with intraosseous growth. Anticancer research. 2007 Jul-Aug:27(4C):2573-81 [PubMed PMID: 17695417]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBahrami A, Folpe AL. Adult-type fibrosarcoma: A reevaluation of 163 putative cases diagnosed at a single institution over a 48-year period. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2010 Oct:34(10):1504-13. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181ef70b6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20829680]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceReshadi H, Rouhani A, Mohajerzadeh S, Moosa M, Elmi A. Prevalence of malignant soft tissue tumors in extremities: an epidemiological study in syria. The archives of bone and joint surgery. 2014 Jun:2(2):106-10 [PubMed PMID: 25207328]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHattinger CM, Tarkkanen M, Benini S, Pasello M, Stoico G, Bacchini P, Knuutila S, Scotlandi K, Picci P, Serra M. Genetic analysis of fibrosarcoma of bone, a rare tumour entity closely related to osteosarcoma and malignant fibrous histiocytoma of bone. European journal of cell biology. 2004 Sep:83(9):483-91 [PubMed PMID: 15540465]

Suurmeijer AJH, Xu B, Torrence D, Dickson BC, Antonescu CR. Kinase fusion positive intra-osseous spindle cell tumors: A series of eight cases with review of the literature. Genes, chromosomes & cancer. 2023 Oct 2:():. doi: 10.1002/gcc.23205. Epub 2023 Oct 2 [PubMed PMID: 37782551]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCozzolino I, Caleo A, Di Crescenzo V, Cinelli M, Carlomagno C, Garzi A, Vitale M. Cytological diagnosis of adult-type fibrosarcoma of the neck in an elderly patient. Report of one case and review of the literature. BMC surgery. 2013:13 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-13-S2-S42. Epub 2013 Oct 8 [PubMed PMID: 24266985]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZindanci I, Zemheri E, Kavala M, Kocaturk E, Can B, Turkoglu Z, Ulucay V, Ozbulak O. Fibrosarcoma arising from a burn scar. European journal of dermatology : EJD. 2011 Nov-Dec:21(6):996-7. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2011.1505. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21865123]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMorrison BA. Soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center). 2003 Jul:16(3):285-90 [PubMed PMID: 16278699]

McLEOD JJ, DAHLIN DC, IVINS JC. Fibrosarcoma of bone. American journal of surgery. 1957 Sep:94(3):431-7 [PubMed PMID: 13458607]

Neuville A, Chibon F, Coindre JM. Grading of soft tissue sarcomas: from histological to molecular assessment. Pathology. 2014 Feb:46(2):113-20. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0000000000000048. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24378389]

André S, Tomeno B, Forest M, Carlioz A. [Fibrosarcoma of bone]. Revue de chirurgie orthopedique et reparatrice de l'appareil moteur. 1983:69(2):107-16 [PubMed PMID: 6223340]

Raza A, Siraj I, Malik S, Mohammed R, Shariff MA. A Case of Locally Advanced Fibrosarcoma in a Young Male. Cureus. 2023 Aug:15(8):e44095. doi: 10.7759/cureus.44095. Epub 2023 Aug 25 [PubMed PMID: 37750151]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBao Q, Niess H, Djafarzadeh R, Zhao Y, Schwarz B, Angele MK, Jauch KW, Nelson PJ, Bruns CJ. Recombinant TIMP-1-GPI inhibits growth of fibrosarcoma and enhances tumor sensitivity to doxorubicin. Targeted oncology. 2014 Sep:9(3):251-61. doi: 10.1007/s11523-013-0294-5. Epub 2013 Aug 10 [PubMed PMID: 23934106]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSlovak ML, Hoeltge GA, Dalton WS, Trent JM. Pharmacological and biological evidence for differing mechanisms of doxorubicin resistance in two human tumor cell lines. Cancer research. 1988 May 15:48(10):2793-7 [PubMed PMID: 2896069]

ESMO/European Sarcoma Network Working Group. Soft tissue and visceral sarcomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2014 Sep:25 Suppl 3():iii102-12. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu254. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25210080]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMankin HJ, Hornicek FJ. Diagnosis, classification, and management of soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer control : journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center. 2005 Jan-Feb:12(1):5-21 [PubMed PMID: 15668648]

Cui Y, Pan Y, Shi X. Complete remission of a case of high-grade myxofibrosarcoma with lung metastases after modified MAID regimen chemotherapy. Journal of chemotherapy (Florence, Italy). 2020 Dec:32(8):451-455. doi: 10.1080/1120009X.2020.1764274. Epub 2020 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 32427061]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBorden EC, Amato DA, Rosenbaum C, Enterline HT, Shiraki MJ, Creech RH, Lerner HJ, Carbone PP. Randomized comparison of three adriamycin regimens for metastatic soft tissue sarcomas. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1987 Jun:5(6):840-50 [PubMed PMID: 3585441]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAntman KH, Ryan L, Elias A, Sherman D, Grier HE. Response to ifosfamide and mesna: 124 previously treated patients with metastatic or unresectable sarcoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1989 Jan:7(1):126-31 [PubMed PMID: 2491883]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMa H, Fang J, Wang T, Wang D, Wang L, Wang C, Tang L, Tang Y, Lu S, Wang Y, Chen X. Efficacy and Safety of Apatinib in the Treatment of Postoperative Recurrence of Fibrosarcoma. OncoTargets and therapy. 2020:13():1717-1721. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S214829. Epub 2020 Feb 25 [PubMed PMID: 32158235]

Choi Y, Yun MS, Lim SH, Lee J, Ahn JH, Kim YJ, Park KH, Park YS, Lim HY, An H, Suh DC, Kim YH. Gemcitabine and Docetaxel Combination for Advanced Soft Tissue Sarcoma: A Nationwide Retrospective Study. Cancer research and treatment. 2018 Jan:50(1):175-182. doi: 10.4143/crt.2016.535. Epub 2017 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 28361521]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePollack SM, Redman MW, Baker KK, Wagner MJ, Schroeder BA, Loggers ET, Trieselmann K, Copeland VC, Zhang S, Black G, McDonnell S, Gregory J, Johnson R, Moore R, Jones RL, Cranmer LD. Assessment of Doxorubicin and Pembrolizumab in Patients With Advanced Anthracycline-Naive Sarcoma: A Phase 1/2 Nonrandomized Clinical Trial. JAMA oncology. 2020 Nov 1:6(11):1778-1782. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.3689. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32910151]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSong L, Pan D, Zhou R. Combination nivolumab and bevacizumab for metastatic myxofibrosarcoma: A case report and review of the literature. Molecular and clinical oncology. 2020 Nov:13(5):54. doi: 10.3892/mco.2020.2124. Epub 2020 Aug 24 [PubMed PMID: 32905214]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTaconis WK, Mulder JD. Fibrosarcoma and malignant fibrous histiocytoma of long bones: radiographic features and grading. Skeletal radiology. 1984:11(4):237-45 [PubMed PMID: 6328676]

Van den Berg E, Molenaar WM, Hoekstra HJ, Kamps WA, de Jong B. DNA ploidy and karyotype in recurrent and metastatic soft tissue sarcomas. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 1992 Sep:5(5):505-14 [PubMed PMID: 1344814]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLimon J, Szadowska A, Iliszko M, Babińska M, Mrózek K, Jaśkiewicz J, Kopacz A, Roszkiewicz A, Debiec-Rychter M. Recurrent chromosome changes in two adult fibrosarcomas. Genes, chromosomes & cancer. 1998 Feb:21(2):119-23 [PubMed PMID: 9491323]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStoeckle E, Michot A, Rigal L, Babre F, Sargos P, Henriques de Figueiredo B, Brouste V, Italiano A, Toulmonde M, Le Loarer F, Kind M. The risk of postoperative complications and functional impairment after multimodality treatment for limb and trunk wall soft-tissue sarcoma: Long term results from a monocentric series. European journal of surgical oncology : the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology. 2017 Jun:43(6):1117-1125. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2017.01.018. Epub 2017 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 28202211]