Introduction

The first use of nuclear medicine to evaluate gastric motility was performed in 1966 by Dr. Griffith and colleagues of Cardiff, Wales, using a breakfast meal labeled with Chromium-51.[1] By measuring the amount of radioactivity in the stomach (gastric counts) at various time points, they could directly determine the volume of a meal remaining in the stomach and thus determine the rate of gastric emptying (GE). Since then, the modern version of the exam, known as gastric emptying scintigraphy (GES) has become a common diagnostic tool in the assessment of patients with various functional gastrointestinal disorders.

Other tests used to measure GE include breath testing and wireless pH capsules. Breath testing is performed using a standardized meal including Spirulina labeled with Carbon-13. The meal passes through the stomach, into the duodenum where it is absorbed, metabolized in the liver and exhaled by the lungs where it is measured. As transit of the meal through the stomach is the rate-limiting step in the process, the test serves as an indirect measurement of GE, assuming normal bowel, liver, and pulmonary function. The wireless pH capsule test is performed by administering a capsule in conjunction with a nutrient bar. The capsule is monitored by a belt worn by the patient and transit from the stomach to small bowel is detected by a sudden increase in pH, denoting transition from the acidic stomach to the alkaline duodenum.

Given its noninvasive nature and physiologic methodology compared to these other tests, scintigraphy has become the prevailing means by which to measure gastric emptying (GE).

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The stomach is in the left upper quadrant (LUQ) of the abdomen and is comprised of four functional components: the fundus (proximal), body (mid) and antrum (distal) as well as the pylorus. The fundus is posterolateral and the antrum is anteromedial with the long axis of the stomach oriented obliquely, from the LUQ to the epigastric region. The fundus has two functions. It relaxes with the entrance of solids and liquids, a process called accommodation, and then contracts to provide a pressure gradient which moves the meal distal. The body is a reservoir for mixing of ingested material and serves as the pacemaker for the stomach. The antrum is essential in the handling of solids through a process called trituration, grinding the food into 1 to 2 mm particles through repetitive contractions. Once it reaches this threshold size, the pylorus, which serves to control transit of ingested material out of the stomach, will allow it to pass into the duodenum.[2]

Indications

Gastric emptying scintigraphy (GES) is typically obtained to assess for gastroparesis in patients with post-prandial symptoms of nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and/or early satiety. GES can also provide important information in patients with esophageal reflux unresponsive to therapy or in diabetics with poor glycemic control to confirm or exclude delayed gastric emptying as a contributing factor in a patient’s poor response to therapy.[3] Additionally, GES is beneficial in the evaluation of patients with colonic inertia being considered for colectomy since individuals with concurrent delayed gastric emptying have a much lower response rate to surgery than those with normal GE.[4]

More recently, GES has been used to evaluate for rapid gastric emptying, which can be seen early in the course of diabetes as well as with cyclic vomiting syndrome, a disorder manifested by recurrent episodes of nausea, vomiting, and lethargy.[5]

Contraindications

- Allergies to the recommended meal

- Hyperglycemia in diabetics (blood glucose greater than 250 to 275 mg/dL)[6]

Equipment

The components of a meal (size, digestibility, calories and nutrient content) all affect the rate of gastric emptying. Solids and fats empty more slowly, whereas liquids, proteins, and carbohydrates empty more rapidly.[7][8][9] Until recently, no standard existed for the meal used in GES. Different methodologies were used at different imaging clinics (orange juice, cereal with milk, oatmeal, scrambled eggs, chicken liver), and as a result, they often had different normal values. This was of concern to clinicians because study results from separate imaging facilities made interpretation and comparison of results problematic. As a result, in 2007 an expert panel of gastroenterologists and nuclear medicine physicians met to decide on consensus standards for gastric emptying scintigraphy. These recommendations were published in 2008.

The standardized meal described in the GES guideline is a solid meal consisting of 0.5 to 1.0 mCi of 99mTc-sulfur colloid scrambled with 120 grams of liquid egg whites (Egg Beaters or generic), 2 slices of white toast, 30 grams of strawberry jelly, and 120 mL of water.[6] It is recommended that this exact meal be utilized for all adult solid gastric emptying scintigraphy studies. The departure of the test meal from this standard precludes accurate comparison to validated normal values and thus, may factitiously alter the diagnosis of normal versus abnormal gastric emptying.

To date, the consensus guidelines only address gastric emptying in regards to a solid meal. However, liquids and solids empty differently from the stomach. Solids generally show early fundal localization (via accommodation) while liquids distribute quickly throughout the stomach. Also, given that liquids do not undergo trituration (an antral function), they empty predominantly via the control of the fundal pressure gradient. This difference may result in some patients with isolated mild-to-moderate fundal dysfunction not being accurately identified on the standard solid gastric emptying study. To overcome this potential inadequacy of GES, additional research has been done regarding the use of a liquid meal. One of the most widely accepted standards was developed by Ziessman and colleagues at Johns Hopkins, using a non-nutrient meal comprised simply of 300 mL water labeled with 0.2 mCi of Tc-99m sulfur colloid or Indium-111 DTPA.[10][11]

Personnel

A nuclear medicine technologist performs GES exams under the supervision of a nuclear medicine physician or nuclear radiologist.

Preparation

Proper patient preparation is critical to performing an accurate and reliable GES.

- Prokinetic agents such as metoclopramide, erythromycin, tegaserod, and domperidone should be discontinued for 2 days before the study unless the test is performed to assess the efficacy of these medications.

- Medications that delay gastric emptying should also be discontinued for 2 days before the exam. These include opiates (e.g., morphine, codeine, and oxycodone) and antispasmodic agents such as atropine, dicyclomine, loperamide, and promethazine.

- Patients should not eat or drink for a minimum of 4 hours before the study. It is typical for the patient to take nothing by mouth starting at midnight and then undergo the exam in the morning.

- Insulin-dependent diabetic patients should bring their insulin and glucose monitors with them. Their blood sugar should ideally less than 200 mg/dL. Diabetic patients should monitor their glucose level and adjust their morning dose of insulin as needed for the prescribed meal.

- Additionally, it may be best to schedule exams for premenopausal women on days 1 to 10 of their menstrual cycle, to avoid the effects of hormonal changes on gastric emptying that has been shown in some, but not all studies.[6]

Technique or Treatment

To prepare the solid meal, the liquid egg whites are poured into a bowl, mixed with 0.5 to 1 mCi 99Tc sulfur colloid and cooked in a nonstick frying pan or microwave (Of note, simply adding the sulfur colloid after cooking the egg whites will result in poor labeling and lead to spurious measurements). The egg and radiopharmaceutical mixture should be stirred once or twice during cooking and cooked until it reaches the consistency of an omelet. The bread is toasted, jelly is spread on the toast, and a sandwich is made of the jellied bread and cooked egg mixture.[12] The meal should be consumed within 10 minutes, and imaging commences.

In addition to standardizing the meal, the consensus guidelines released in 2008 standardized the imaging and interpretation, endorsing a protocol developed in 2000 by Tougas and colleagues.[13] This simplified methodology for solid GES requires 1-minute images be acquired at only 4 time points: immediately after meal ingestion and at 1, 2, and 4 hours with an optional fifth time point at 30-minutes which can be helpful in the assessment of rapid gastric emptying.

The images are ideally acquired simultaneously in the anterior and posterior projections using a dual-head gamma camera with field-of-view (FOV) encompassing the entire stomach as well as the distal esophagus and proximal small bowel. If a dual-head gamma camera is not available, sequential anterior and then posterior images from a single-head gamma camera is an acceptable technique. The counts in the stomach are then measured by drawing a region-of-interest (ROI) around the stomach. Using the first time point (T=0) as the baseline (which includes all activity, to include any which has already traversed the stomach), the amount of activity retained in the stomach at each subsequent time point can be calculated using the geometric mean with decay correction and compared to validated normal values.

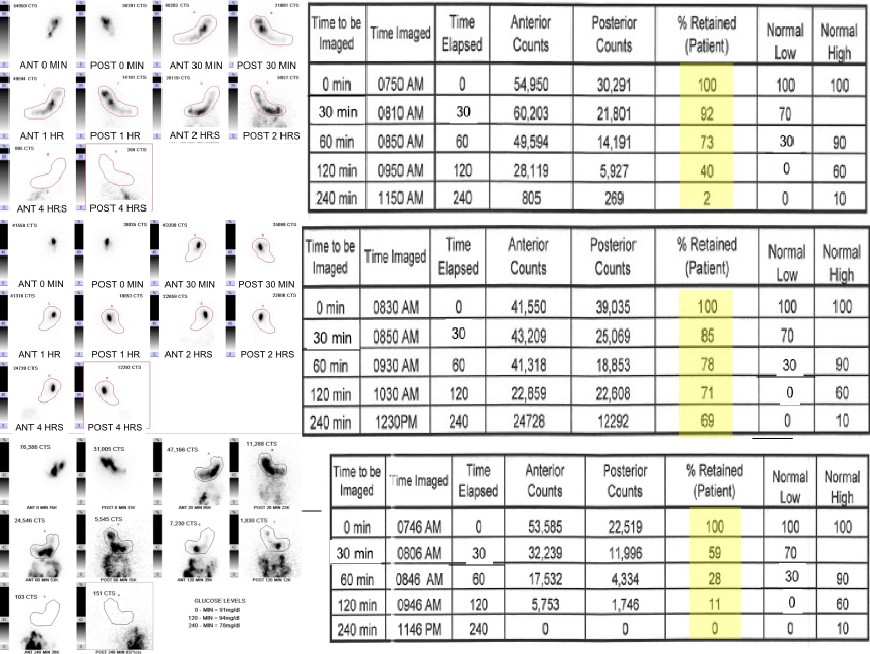

The published normal values are (FIG1)[14]:

- Thirty minutes: Greater than or equal to 70% meal retention

- One hour: 30% to 90% meal retention

- Two hours: Less than or equal to 60% meal retention

- Four hours: Less than or equal to 10% meal retention

- A retained meal value greater than 60% at 2 hours or 10% at 4 hours supports delayed gastric emptying (FIG2)

- A retained meal value less than 70% at 30 minutes or less than 30% at 1 hour suggests rapid gastric emptying (FIG3)[13][12]

If utilizing a liquid meal, the radiopharmaceutical is simply mixed with the 300 mL of water. The exam is then performed with the patient positioned semi-upright (45-degree angle) and imaging performed with a single-head gamma camera in the left anterior oblique projection (along the long axis of the stomach). Imaging starts immediately after the ingestion of the radiolabeled water with images acquired as 1-min frames continuously for 30 minutes. Like with solid gastric emptying, an ROI is drawn over the stomach to measure gastric retention. Unlike with solid gastric emptying, no geometric mean is calculated given the single-head camera technique and the rapid nature of liquid only emptying necessitates a time-activity-curve (TAC) be generated using each time point to calculate the time to reach 50% emptying (T-1/2). Using this protocol, a T-1/2 of fewer than 22 minutes is considered normal (mean plus 3 standard deviations).[10]

Complications

Factors that may affect the performance and negatively influence the clinical validity of a GES are:

- Incomplete meal consumption

- Slow meal consumption (taking longer than 10 minutes)

- Vomiting a portion of the meal

- Poor glycemic control

If these problems occur, they should be included in the exam report as well as a comment as to their potential impact on the accuracy of the results.

Clinical Significance

Gastroparesis and rapid gastric emptying are conditions of abnormal gastric motility in the absence of obstructive pathology.

Gastroparesis was classically thought to be the sequela of previous stomach surgery or the result of long-standing diabetes.[15] More recently, it has been found to most likely be idiopathic (32% of cases) with diabetes the second most common cause (29%) and surgery third (13%). Interestingly, women are afflicted 4-to-1 in comparison to men.[16] Given its most common presenting symptoms (nausea, pain, bloating) overlap with a multitude of other diseases, exact prevalence of delayed gastric emptying (DGE) is unknown, though it is estimated in the US that two-thirds of the country's 23 million people with diabetes suffer from gastroparesis while gastric dysmotility is present in 40% of adults with dyspepsia.[17]

Similar to DGE, rapid gastric empty is identified more commonly than previously suspected. It has been found in nearly 60% of patients with cyclic vomiting syndrome who undergo GES as well as a large proportion of individuals with autonomic dysfunction.[18]

Given this high prevalence of disease and its substantial impact on public health, it is critical that those afflicted be appropriately diagnosed to guide proper treatment and effective management. Key to this is the use of properly performed gastric emptying scintigraphy following standardized consensus guidelines. Research has shown that by using these parameters appropriately, the diagnostic yield of the GES can be improved significantly. Imaging of solid gastric emptying out to 4 hours, as recommended, increases sensitivity by a third over historical protocols that limited imaging to 2 or fewer hours. Adding a liquid GES study in patients with a normal solid GE can further increase detection of gastroparesis by another third.[19] By identifying more patients with abnormal gastric emptying, it will lead to more accurate diagnoses, which in turn will hopefully result in further development of therapies and improved care.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Disorders of gastric emptying often present with the symptoms of dyspepsia, post-prandial pain, bloating, early satiety, nausea, and vomiting. Such non-specific symptoms are frequently encountered by primary care providers, emergency department providers, surgeons, and gastroenterologists. The list of possible etiologies is extensive and includes gastric disorders, biliary disease, intestinal diseases, metabolic disorders, vascular pathology, and psychiatric diagnoses. Even after a thorough clinical history, physical exam and laboratory assessment, the definitive cause often remains in doubt. As such, subspecialty referrals are often sought, leading to these patients being evaluated by surgeons suspecting chronic cholecystitis, gastroenterologists concerned for peptic ulcer disease, vascular surgeons suspecting mesenteric ischemia, and mental health providers assessing for depression or anxiety. Of benefit to all these primary and subspecialty providers and their challenging patients is the well performed gastric emptying scintigraphy (GES) study following consensus guidelines. It provides a validated and reproducible means to accurately identify patients with gastroparesis or rapid gastric emptying as a potential source of their clinical complaints.

Media

References

Griffith GH, Owen GM, Kirkman S, Shields R. Measurement of rate of gastric emptying using chromium-51. Lancet (London, England). 1966 Jun 4:1(7449):1244-5 [PubMed PMID: 4161213]

Parkman HP, Jones MP. Tests of gastric neuromuscular function. Gastroenterology. 2009 May:136(5):1526-43. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.039. Epub 2009 Mar 16 [PubMed PMID: 19293005]

Ziessman HA. Gastrointestinal Transit Assessment: Role of Scintigraphy: Where Are We Now? Where Are We Going? Current treatment options in gastroenterology. 2016 Dec:14(4):452-460 [PubMed PMID: 27682148]

Verne GN, Hocking MP, Davis RH, Howard RJ, Sabetai MM, Mathias JR, Schuffler MD, Sninsky CA. Long-term response to subtotal colectomy in colonic inertia. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery : official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2002 Sep-Oct:6(5):738-44 [PubMed PMID: 12399064]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHejazi RA, Lavenbarg TH, McCallum RW. Spectrum of gastric emptying patterns in adult patients with cyclic vomiting syndrome. Neurogastroenterology and motility. 2010 Dec:22(12):1298-302, e338. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01584.x. Epub 2010 Aug 19 [PubMed PMID: 20723071]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDonohoe KJ, Maurer AH, Ziessman HA, Urbain JL, Royal HD, Martin-Comin J, Society for Nuclear Medicine, American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society. Procedure guideline for adult solid-meal gastric-emptying study 3.0. Journal of nuclear medicine technology. 2009 Sep:37(3):196-200. doi: 10.2967/jnmt.109.067843. Epub 2009 Aug 19 [PubMed PMID: 19692450]

Calbet JA, MacLean DA. Role of caloric content on gastric emptying in humans. The Journal of physiology. 1997 Jan 15:498 ( Pt 2)(Pt 2):553-9 [PubMed PMID: 9032702]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChristian PE, Moore JG, Sorenson JA, Coleman RE, Weich DM. Effects of meal size and correction technique on gastric emptying time: studies with two tracers and opposed detectors. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 1980 Sep:21(9):883-5 [PubMed PMID: 7411222]

Hunt JN, Stubbs DF. The volume and energy content of meals as determinants of gastric emptying. The Journal of physiology. 1975 Feb:245(1):209-25 [PubMed PMID: 1127608]

Ziessman HA, Chander A, Clarke JO, Ramos A, Wahl RL. The added diagnostic value of liquid gastric emptying compared with solid emptying alone. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2009 May:50(5):726-31. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.059790. Epub 2009 Apr 16 [PubMed PMID: 19372480]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceZiessman HA, Okolo PI, Mullin GE, Chander A. Liquid gastric emptying is often abnormal when solid emptying is normal. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2009 Aug:43(7):639-43 [PubMed PMID: 19623689]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAbell TL, Camilleri M, Donohoe K, Hasler WL, Lin HC, Maurer AH, McCallum RW, Nowak T, Nusynowitz ML, Parkman HP, Shreve P, Szarka LA, Snape WJ Jr, Ziessman HA, American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and the Society of Nuclear Medicine. Consensus recommendations for gastric emptying scintigraphy: a joint report of the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and the Society of Nuclear Medicine. Journal of nuclear medicine technology. 2008 Mar:36(1):44-54. doi: 10.2967/jnmt.107.048116. Epub 2008 Feb 20 [PubMed PMID: 18287197]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTougas G, Chen Y, Coates G, Paterson W, Dallaire C, Paré P, Boivin M, Watier A, Daniels S, Diamant N. Standardization of a simplified scintigraphic methodology for the assessment of gastric emptying in a multicenter setting. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2000 Jan:95(1):78-86 [PubMed PMID: 10638563]

Abell TL, Camilleri M, Donohoe K, Hasler WL, Lin HC, Maurer AH, McCallum RW, Nowak T, Nusynowitz ML, Parkman HP, Shreve P, Szarka LA, Snape WJ Jr, Ziessman HA, American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and the Society of Nuclear Medicine. Consensus recommendations for gastric emptying scintigraphy: a joint report of the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and the Society of Nuclear Medicine. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2008 Mar:103(3):753-63 [PubMed PMID: 18028513]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBielefeldt K. Gastroparesis: concepts, controversies, and challenges. Scientifica. 2012:2012():424802. doi: 10.6064/2012/424802. Epub 2012 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 24278691]

Soykan I, Sivri B, Sarosiek I, Kiernan B, McCallum RW. Demography, clinical characteristics, psychological and abuse profiles, treatment, and long-term follow-up of patients with gastroparesis. Digestive diseases and sciences. 1998 Nov:43(11):2398-404 [PubMed PMID: 9824125]

Harmon RC, Peura DA. Evaluation and management of dyspepsia. Therapeutic advances in gastroenterology. 2010 Mar:3(2):87-98. doi: 10.1177/1756283X09356590. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21180593]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMaurer AH. Advancing gastric emptying studies: standardization and new parameters to assess gastric motility and function. Seminars in nuclear medicine. 2012 Mar:42(2):101-12. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2011.10.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22293165]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAntoniou AJ, Raja S, El-Khouli R, Mena E, Lodge MA, Wahl RL, Clarke JO, Pasricha P, Ziessman HA. Comprehensive radionuclide esophagogastrointestinal transit study: methodology, reference values, and initial clinical experience. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2015 May:56(5):721-7. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.152074. Epub 2015 Mar 12 [PubMed PMID: 25766893]