Introduction

Gilbert syndrome is an autosomal recessive disorder of bilirubin metabolism within the liver.[1][2] Reduced glucuronidation of bilirubin leads to unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia and recurrent episodes of jaundice.[1] Under normal circumstances, approximately 95% of bilirubin is unconjugated. Gilbert syndrome does not require treatment and must be distinguished from other disorders of unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia.[3] Alternative diseases should be considered in evaluating patients with unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, including disorders of bilirubin uptake, conjugation, and overproduction.[4]

Disorders of hepatic uptake, storage, conjugation, and excretion can cause unconjugated and conjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Crigler-Najjar syndrome is characterized by marked unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia.[5] Hemolytic reactions, ineffective erythropoiesis, and resorbing hematomas induce bilirubin overproduction and subsequent unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Hemolytic reactions include but are not limited to hereditary enzyme deficiencies, hemoglobinopathies, red blood cell membrane defects, infections, medications, toxins, warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia, paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria, and cold agglutinin disease that can lead to elevated unconjugated bilirubin levels.[6][7] Most patients with Gilbert syndrome are asymptomatic regarding liver disease, but they may express symptoms related to triggers. Triggers that can precipitate unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia of Gilbert syndrome include but are not limited to fasting, intercurrent illness, menstruation, and dehydration.[3]

Other acute and chronic liver diseases typically present with both unconjugated and conjugated hyperbilirubinemia.[8] With hepatobiliary disorders, the proportion of conjugated bilirubin rises. Consequently, consideration of viral, metabolic, and autoimmune disorders of the liver is necessary when evaluating patients with hyperbilirubinemia and jaundice. Careful clinical assessment, targeted laboratory evaluation, exclusion of other conditions associated with unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, and consideration of other acute and chronic liver diseases should be done before diagnosing Gilbert syndrome. After diagnosing Gilbert syndrome, treatment is conservative with observation alone.[3] The prognosis of patients with Gilbert syndrome is excellent.[9]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia and jaundice in patients with Gilbert syndrome can be precipitated by a variety of triggers. Fasting, hemolytic reactions, febrile illnesses, menstruation, and physical exertion are common precipitants.[3][10] A reduction in the daily caloric intake to 400 kcal can lead to a 2 to 3 fold increase of bilirubin within 48 hours.[10][11] Moreover, a similar rise in bilirubin can present with a normocaloric diet without lipid supplementation.[12] The bilirubin value typically returns to normal within 12 to 24 hours with a normal diet.

Several theories have been proposed to explain unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia following dietary manipulation. Increased cycling of bilirubin by the enterohepatic circulation, decreased conjugation due to a decrease in the levels of UDP-glucuronic acid, which is a co-substrate in glucuronidation, and release of bilirubin from fat cells.[13][14][15]

Epidemiology

Gilbert syndrome has a prevalence rate between 4 and 16%.[16][17][18] Clinical manifestations are characteristically present during early adolescence and are more frequently found in males.[19] Most likely, differences in sex steroid concentrations and higher bilirubin production in males account for higher prevalence rates.[19] Most cases are diagnosed around puberty due to higher hemoglobin turnover and endogenous steroid hormone-induced inhibition of bilirubin glucuronidation.[19] The frequency of the variant promoter (to be described below) is 30% among whites and blacks; the promoter mutation is less frequent in patients from Japan.[20][21] Patients with Gilbert syndrome and glucose-6-phosphatase deficiency are susceptible to prolonged neonatal jaundice.[22][23]

Pathophysiology

As previously mentioned, Gilbert syndrome is generally thought to be inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. Uridine diphosphoglucuronate-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 (UG1A1) is important for converting unconjugated to conjugated bilirubin.[22][23] Conjugated bilirubin is water-soluble and readily excreted in bile.

Homozygosity for a defect in the TATAA box within the promoter region of the gene for UG1A1 leads to a mutation of UG1A1 called UG1A1*28. The molecular defect inserts an additional dinucleotide sequence (TA) into the transcription initiation sequence: A(TA)6TAA to A(TA)7TAA.[1] UG1A1 activity is only 30% of normal in patients with Gilbert syndrome.[24]. Monoconjugated bile pigments are increased by 34% in this patient group.[24] Patients who are heterozygous for the mutation have serum bilirubin values higher than the normal population. Not all homozygous patients for the promoter mutation will develop Gilbert syndrome, as other factors may be important for clinical expression.[20]

Histopathology

Liver biopsy is generally not required for patients suspected of having Gilbert syndrome unless other confounding diagnoses merit consideration. Histopathology typically reveals non-specific lipofuscin pigment found within the centrilobular region of the biopsy specimen; otherwise, the histology is normal.[25]

Toxicokinetics

UG1A1 is involved in the metabolism of estrogen and several other drugs through glucuronidation. Hence, individuals with Gilbert syndrome may be susceptible to toxicities from medications that require glucuronidation. Irinotecan is well-known to cause toxicity in patients with Gilbert syndrome.[26][27] The active metabolite SN-38 accumulates and can cause diarrhea and myelosuppression. Atazanavir and Indinavir inhibit UG1A1 and may cause hyperbilirubinemia.[28] Acetaminophen, menthol, estradiol benzoate, lamotrigine, rifamycin SV require glucuronidation, but avoidance is generally not recommended.[29][30][31]

History and Physical

Gilbert syndrome typically appears during adolescence.[19] Males are more commonly affected than females.[19] Except for mild jaundice, patients are usually asymptomatic from liver disease but may have complaints attributable to triggers outlined above.[3][10] Patients with Gilbert syndrome have an increased incidence of gallstones.[32][33][34] Underlying hemolytic reactions result in bilirubin overproduction and may cause unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia.[6][7]

The provider needs to consider other acute and chronic liver diseases based upon the history and physical examination. Patients should be questioned about a history of significant alcohol use, which can lead to fatty liver, steatohepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.[35] Alcoholic hepatitis and decompensated cirrhosis are associated with high mortality not seen in patients with Gilbert syndrome. Additionally, a history of recreational drug use, blood transfusions, body piercing, sex with an intravenous drug user, incarceration, religious scarification, immunoglobulin injection, tattoos, country of birth, and high-risk sexual activity should be obtained, which may suggest either hepatitis B or C.[36][37]

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease should be considered for patients with a history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity.[38]. Non-alcoholic fatty liver is rapidly becoming one of the most common liver diseases in the United States.[38] A careful history pertaining to autoimmune diseases in the patient or family may point towards a consideration of primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, or autoimmune hepatitis.[39] Patients with Gilbert syndrome do not have evidence of hepatic decompensation manifested by variceal bleeding, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, hepatorenal or hepatopulmonary syndromes, portopulmonary hypertension, or extrahepatic disorders associated with portal hypertension.

Evaluation

Gilbert syndrome is associated with unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia; the bilirubin is typically below 4 mg/dL; however, the bilirubin level can fluctuate depending on exacerbating factors.[3] Characteristically, patients will have a normal complete blood count, reticulocyte count, lactate dehydrogenase, and peripheral smear.[40] Moreover, the aminotransferases and alkaline phosphatase are normal.[41][42][43]

Diagnostic imaging of the liver and biliary tree is generally not required unless the provider is considering another diagnosis. As previously discussed, liver biopsy is rarely indicated unless one suspects another acute or chronic liver disorder. Provocative testing with a 48 hour fast or low-calorie diet is generally not indicated. Genetic testing with assays of UG1A1 activity and polymerase chain reaction to identify gene polymorphisms in the TATAA box of UG1A1 should be considered for diagnostic uncertainty.[17]

The provider should have a low threshold to consider other liver diseases that may cause hyperbilirubinemia before diagnosing Gilbert syndrome, as outlined above. If viral hepatitis is suspected, serologic tests for hepatitis A, B, and C should be considered.[44][36][45] If autoimmune hepatitis is a possibility, appropriate serology, quantitative immunoglobulins, and liver biopsy may be in order.[39] Laboratory evaluation, including serology with or without liver biopsy, is suggested for patients with suspected primary biliary cholangitis.[39] Testing for ceruloplasmin, serum, urine copper studies, liver biopsy, and slit-lamp examination for Kayser-Fleisher rings should be considered for suspected Wilson disease.[46] Finally, alpha-1-antitrypsin level and genotype would be appropriate if alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency is a consideration.[47]

Treatment / Management

Patients with Gilbert syndrome do not require treatment.[3] Unnecessary testing should be avoided. Control of potential triggers may be useful to minimize fluctuations in unconjugated bilirubin.[3] Patients presenting with hyperbilirubinemia in combination with abnormalities in aminotransferases and alkaline phosphatase will require further investigation, including testing for viral, metabolic, autoimmune, or drug-induced liver diseases as discussed above. Moreover, the clinician should have a low threshold to get appropriate imaging of the liver and biliary tract when either the clinical presentation or liver-associated enzymes point to a different diagnosis. Patients with evidence of hepatic decompensation, including but not limited to variceal bleeding, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy, should be referred to gastroenterologists or hepatologists for additional workup, treatment, and possible liver transplant evaluation.[48](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Unconjugated Hyperbilirubinemia

- Increased bilirubin production: extravascular and intravascular hemolysis, resorbing hematoma, dyseryrthopoiesis, Wilson disease

- Impaired hepatic bilirubin uptake: heart failure, portosystemic shunts, Gilbert syndrome, medications

- Impaired bilirubin conjugation: Gilbert syndrome, Crigler-Najjar syndrome types I and II, advanced liver disease[49]

Conjugated Hyperbilirubinemia

- Defect of canalicular organic anion transport: Dubin-Johnson syndrome

- Defect of sinusoidal reuptake of conjugated bilirubin: Rotor syndrome

- Extrahepatic cholestasis: choledocholithiasis, pancreaticobiliary malignancy, primary sclerosing cholangitis, pancreatitis, parasitic infection

- Intrahepatic cholestasis: viral hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, primary biliary cholangitis, drugs and toxins, sepsis, infiltrative diseases, parenteral nutrition, sickle cell disease, pregnancy, end-stage liver disease[49]

Prognosis

Patients with Gilbert syndrome have an excellent prognosis.[3] Outcomes of patients with Gilbert syndrome are similar to that of the general population. The possible beneficial effects of mild unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia include a lower incidence of atherosclerosis, endometrial cancer, Hodkin lymphoma, and cancer-related mortality.[3][29][50]

Complications

Gilbert syndrome is a benign, autosomal recessive inherited disorder of bilirubin metabolism.[3] Consequently, patients with this condition are not at significant risk for progressive liver disease, hepatic decompensation, or liver-related mortality.[3] Patients and their families should be informed of the inherited and benign nature of the disease, and unnecessary testing should be kept to a minimum. As mentioned above, if there is any clinical suspicion of either acute or chronic liver disease based upon the clinical presentation or laboratory studies, a more thorough evaluation should be undertaken for viral, metabolic, and autoimmune liver diseases.

Consultations

Primary care clinicians and associated practice professionals can diagnose and follow Gilbert syndrome.[51] If there is a question about the diagnosis or if patients present with findings suggestive of another acute or chronic liver disease with or without hepatic decompensation, they should be referred to either gastroenterologists or hepatologists for additional evaluation and treatment.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with Gilbert syndrome should be informed about potential triggers such as fasting, intercurrent illness, menstruation, overexertion, hemolytic reactions, and dehydration that may cause a rise in unconjugated bilirubin.[51][10] Avoidance of triggers may be advantageous to reduce anxiety about abnormal bilirubin values. Both patients and their families should be aware of the benign nature of the disorder, its inheritance pattern, and that no treatment is necessary, as outlined above. They should also be informed about the excellent prognosis of Gilbert syndrome.

Pearls and Other Issues

Bilirubin is known to exert an antioxidant effect which may be protective.[3][29][50] Patients with Gilbert syndrome have a lower incidence of ischemic heart disease. Studies have also shown a reduction in the incidence of Hodgkin lymphoma, endometrial cancer, and cancer-related mortality when compared to the general population.[3][29][50] The all-cause mortality rate is lower in individuals with mild hyperbilirubinemia due to Gilbert syndrome compared to the general population. Gilbert syndrome patients are at an increased risk of developing gallstones.[52]

In summary, Gilbert syndrome is a benign, inherited disorder of bilirubin metabolism without the risk of progressive liver disease, hepatic decompensation, or increased mortality. Unnecessary testing should be avoided, and patients should be followed conservatively. Moreover, patients with this disorder may benefit from enhanced cardioprotective and anti-neoplastic effects for the reasons discussed above.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Gilbert syndrome may be encountered by the primary care clinician, associated practice provider, emergency department physician, pediatrician, gastroenterologist, or hepatologist.[51] Health care personnel should be informed about the benign nature of this disorder and its excellent prognosis, as outlined previously. Appropriate and targeted diagnostic testing, as previously discussed, should be carried out, and inappropriate testing should be avoided. For patients whose clinical examination or tests suggest another liver disease or hepatic decompensation, they should be referred to either a gastroenterologist or hepatologist. As with any patient encounter, high-quality, patient-centered, medically and ethically appropriate care is necessary. To enhance patient satisfaction and outcome, careful communication among all health care providers to streamline care should be paramount.

Media

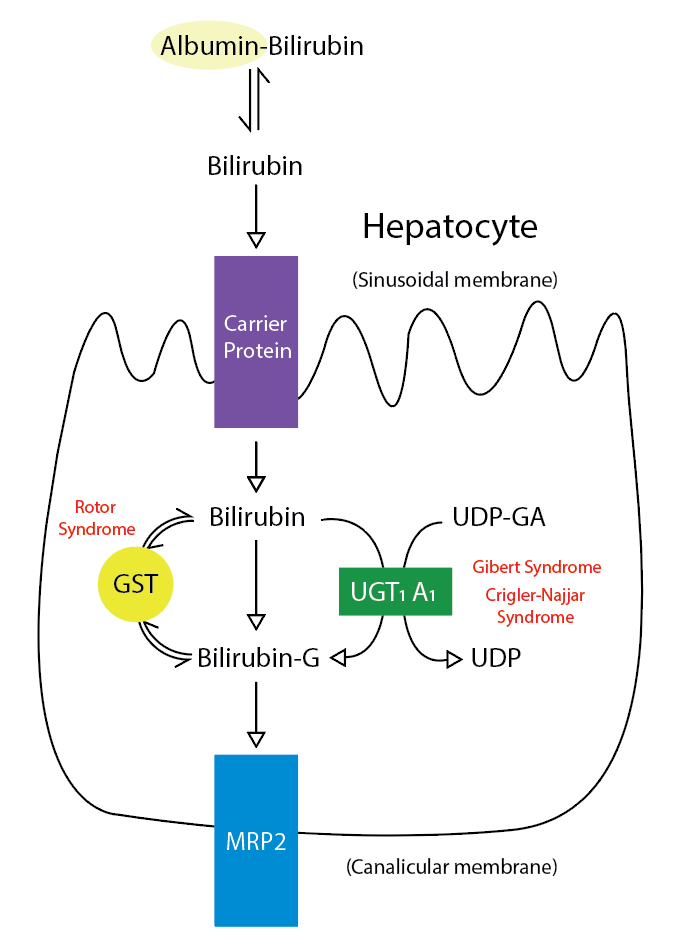

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Metabolic Pathway for Bilirubin in the Hepatocyte. Bilirubin-G corresponds to bilirubin glucuronate; the donor is uridine diphosphate glucuronic acid (UDP-GA). This is catalyzed by the enzyme uridine diphosphate-glucuronyltransferase (UGT1A1). Gilbert and Crigler-Najjar syndrome is associated with decreases in UGT1A1 activity. Glutathione-S-transferase (GST) is a carrier protein that assists bilirubin uptake into the cytosol and may be implicated in Rotor syndrome.

Contributed by R Kabir, MD

References

Bosma PJ. Inherited disorders of bilirubin metabolism. Journal of hepatology. 2003 Jan:38(1):107-17 [PubMed PMID: 12480568]

Burchell B, Hume R. Molecular genetic basis of Gilbert's syndrome. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 1999 Oct:14(10):960-6 [PubMed PMID: 10530490]

Fretzayas A, Moustaki M, Liapi O, Karpathios T. Gilbert syndrome. European journal of pediatrics. 2012 Jan:171(1):11-5. doi: 10.1007/s00431-011-1641-0. Epub 2011 Dec 9 [PubMed PMID: 22160004]

Erlinger S, Arias IM, Dhumeaux D. Inherited disorders of bilirubin transport and conjugation: new insights into molecular mechanisms and consequences. Gastroenterology. 2014 Jun:146(7):1625-38. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.03.047. Epub 2014 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 24704527]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStrauss KA, Ahlfors CE, Soltys K, Mazareigos GV, Young M, Bowser LE, Fox MD, Squires JE, McKiernan P, Brigatti KW, Puffenberger EG, Carson VJ, Vreman HJ. Crigler-Najjar Syndrome Type 1: Pathophysiology, Natural History, and Therapeutic Frontier. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 2020 Jun:71(6):1923-1939. doi: 10.1002/hep.30959. Epub 2020 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 31553814]

Muraca M, Fevery J, Blanckaert N. Relationships between serum bilirubins and production and conjugation of bilirubin. Studies in Gilbert's syndrome, Crigler-Najjar disease, hemolytic disorders, and rat models. Gastroenterology. 1987 Feb:92(2):309-17 [PubMed PMID: 3792767]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMuraca M, Blanckaert N. Liquid-chromatographic assay and identification of mono- and diester conjugates of bilirubin in normal serum. Clinical chemistry. 1983 Oct:29(10):1767-71 [PubMed PMID: 6616822]

Kwo PY, Cohen SM, Lim JK. ACG Clinical Guideline: Evaluation of Abnormal Liver Chemistries. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2017 Jan:112(1):18-35. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.517. Epub 2016 Dec 20 [PubMed PMID: 27995906]

Horsfall LJ, Nazareth I, Pereira SP, Petersen I. Gilbert's syndrome and the risk of death: a population-based cohort study. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2013 Oct:28(10):1643-7. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12279. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23701650]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFelsher BF, Rickard D, Redeker AG. The reciprocal relation between caloric intake and the degree of hyperbilirubinemia in Gilbert's syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. 1970 Jul 23:283(4):170-2 [PubMed PMID: 5424007]

Barrett PV. Hyperbilirubinemia of fasting. JAMA. 1971 Sep 6:217(10):1349-53 [PubMed PMID: 5109641]

Gollan JL, Bateman C, Billing BH. Effect of dietary composition on the unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia of Gilbert's syndrome. Gut. 1976 May:17(5):335-40 [PubMed PMID: 1278716]

Felsher BF, Carpio NM, VanCouvering K. Effect of fasting and phenobarbital on hepatic UDP-glucuronic acid formation in the rat. The Journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 1979 Mar:93(3):414-27 [PubMed PMID: 107254]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKotal P, Vítek L, Fevery J. Fasting-related hyperbilirubinemia in rats: the effect of decreased intestinal motility. Gastroenterology. 1996 Jul:111(1):217-23 [PubMed PMID: 8698202]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrink MA, Méndez-Sánchez N, Carey MC. Bilirubin cycles enterohepatically after ileal resection in the rat. Gastroenterology. 1996 Jun:110(6):1945-57 [PubMed PMID: 8964422]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRaijmakers MT, Jansen PL, Steegers EA, Peters WH. Association of human liver bilirubin UDP-glucuronyltransferase activity with a polymorphism in the promoter region of the UGT1A1 gene. Journal of hepatology. 2000 Sep:33(3):348-51 [PubMed PMID: 11019988]

Borlak J, Thum T, Landt O, Erb K, Hermann R. Molecular diagnosis of a familial nonhemolytic hyperbilirubinemia (Gilbert's syndrome) in healthy subjects. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 2000 Oct:32(4 Pt 1):792-5 [PubMed PMID: 11003624]

Roy-Chowdhury N, Deocharan B, Bejjanki HR, Roy-Chowdhury J, Koliopoulos C, Petmezaki S, Valaes T. Presence of the genetic marker for Gilbert syndrome is associated with increased level and duration of neonatal jaundice. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992). 2002:91(1):100-1 [PubMed PMID: 11883809]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMuraca M, Fevery J. Influence of sex and sex steroids on bilirubin uridine diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferase activity of rat liver. Gastroenterology. 1984 Aug:87(2):308-13 [PubMed PMID: 6428963]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBosma PJ, Chowdhury JR, Bakker C, Gantla S, de Boer A, Oostra BA, Lindhout D, Tytgat GN, Jansen PL, Oude Elferink RP. The genetic basis of the reduced expression of bilirubin UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1 in Gilbert's syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. 1995 Nov 2:333(18):1171-5 [PubMed PMID: 7565971]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMonaghan G, Ryan M, Seddon R, Hume R, Burchell B. Genetic variation in bilirubin UPD-glucuronosyltransferase gene promoter and Gilbert's syndrome. Lancet (London, England). 1996 Mar 2:347(9001):578-81 [PubMed PMID: 8596320]

Black M, Billing BH. Hepatic bilirubin udp-glucuronyl transferase activity in liver disease and gilbert's syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. 1969 Jun 5:280(23):1266-71 [PubMed PMID: 5770050]

Auclair C, Hakim J, Boivin P, Troube H, Boucherot J. Bilirubin and paranitrophenol glucuronyl transferase activities of the liver in patients with Gilbert's syndrome An attempt at a biochemical breakdown of the Gilbert's syndrome. Enzyme. 1976:21(2):97-107 [PubMed PMID: 816648]

Kaplan M. Gilbert's syndrome and jaundice in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficient neonates. Haematologica. 2000:85(E-letters):E01 [PubMed PMID: 11114816]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSAGILD U, DALGAARD OZ, TYGSTRUP N. Constitutional hyperbilirubinemia with unconjugated bilirubin in the serum and lipochrome-like pigment granules in the liver. Annals of internal medicine. 1962 Feb:56():308-14 [PubMed PMID: 14496018]

Iyer L, King CD, Whitington PF, Green MD, Roy SK, Tephly TR, Coffman BL, Ratain MJ. Genetic predisposition to the metabolism of irinotecan (CPT-11). Role of uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase isoform 1A1 in the glucuronidation of its active metabolite (SN-38) in human liver microsomes. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1998 Feb 15:101(4):847-54 [PubMed PMID: 9466980]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBurchell B, Soars M, Monaghan G, Cassidy A, Smith D, Ethell B. Drug-mediated toxicity caused by genetic deficiency of UDP-glucuronosyltransferases. Toxicology letters. 2000 Mar 15:112-113():333-40 [PubMed PMID: 10720749]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLankisch TO, Moebius U, Wehmeier M, Behrens G, Manns MP, Schmidt RE, Strassburg CP. Gilbert's disease and atazanavir: from phenotype to UDP-glucuronosyltransferase haplotype. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 2006 Nov:44(5):1324-32 [PubMed PMID: 17058217]

de Morais SM, Uetrecht JP, Wells PG. Decreased glucuronidation and increased bioactivation of acetaminophen in Gilbert's syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1992 Feb:102(2):577-86 [PubMed PMID: 1732127]

Carulli N, Ponz de Leon M, Mauro E, Manenti F, Ferrari A. Alteration of drug metabolism in Gilbert's syndrome. Gut. 1976 Aug:17(8):581-7 [PubMed PMID: 976795]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMiners JO, McKinnon RA, Mackenzie PI. Genetic polymorphisms of UDP-glucuronosyltransferases and their functional significance. Toxicology. 2002 Dec 27:181-182():453-6 [PubMed PMID: 12505351]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencedel Giudice EM, Perrotta S, Nobili B, Specchia C, d'Urzo G, Iolascon A. Coinheritance of Gilbert syndrome increases the risk for developing gallstones in patients with hereditary spherocytosis. Blood. 1999 Oct 1:94(7):2259-62 [PubMed PMID: 10498597]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOriga R, Galanello R, Perseu L, Tavazzi D, Domenica Cappellini M, Terenzani L, Forni GL, Quarta G, Boetti T, Piga A. Cholelithiasis in thalassemia major. European journal of haematology. 2009 Jan:82(1):22-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2008.01162.x. Epub 2008 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 19021734]

Haverfield EV, McKenzie CA, Forrester T, Bouzekri N, Harding R, Serjeant G, Walker T, Peto TE, Ward R, Weatherall DJ. UGT1A1 variation and gallstone formation in sickle cell disease. Blood. 2005 Feb 1:105(3):968-72 [PubMed PMID: 15388579]

Seitz HK, Bataller R, Cortez-Pinto H, Gao B, Gual A, Lackner C, Mathurin P, Mueller S, Szabo G, Tsukamoto H. Alcoholic liver disease. Nature reviews. Disease primers. 2018 Aug 16:4(1):16. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0014-7. Epub 2018 Aug 16 [PubMed PMID: 30115921]

Murphy EL, Bryzman SM, Glynn SA, Ameti DI, Thomson RA, Williams AE, Nass CC, Ownby HE, Schreiber GB, Kong F, Neal KR, Nemo GJ. Risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection in United States blood donors. NHLBI Retrovirus Epidemiology Donor Study (REDS). Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 2000 Mar:31(3):756-62 [PubMed PMID: 10706569]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOtt JJ, Stevens GA, Groeger J, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection: new estimates of age-specific HBsAg seroprevalence and endemicity. Vaccine. 2012 Mar 9:30(12):2212-9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.116. Epub 2012 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 22273662]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYounossi ZM, Stepanova M, Afendy M, Fang Y, Younossi Y, Mir H, Srishord M. Changes in the prevalence of the most common causes of chronic liver diseases in the United States from 1988 to 2008. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2011 Jun:9(6):524-530.e1; quiz e60. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.03.020. Epub 2011 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 21440669]

Fischer HP, Goltz D. [Autoimmune liver diseases]. Der Pathologe. 2020 Sep:41(5):444-456. doi: 10.1007/s00292-020-00807-7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32749523]

Wagner KH, Shiels RG, Lang CA, Seyed Khoei N, Bulmer AC. Diagnostic criteria and contributors to Gilbert's syndrome. Critical reviews in clinical laboratory sciences. 2018 Mar:55(2):129-139. doi: 10.1080/10408363.2018.1428526. Epub 2018 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 29390925]

Vierling JM, Berk PD, Hofmann AF, Martin JF, Wolkoff AW, Scharschmidt BF. Normal fasting-state levels of serum cholyl-conjugated bile acids in Gilbert's syndrome: an aid to the diagnosis. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 1982 May-Jun:2(3):340-3 [PubMed PMID: 7076117]

Douglas JG, Beckett GJ, Nimmo IA, Finlayson ND, Percy-Robb IW. Bile salt measurements in Gilbert's syndrome. European journal of clinical investigation. 1981 Dec:11(6):421-3 [PubMed PMID: 6800816]

Okolicsanyi L, Fevery J, Billing B, Berthelot P, Thompson RP, Schmid R, Berk PD. How should mild, isolated unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia be investigated? Seminars in liver disease. 1983 Feb:3(1):36-41 [PubMed PMID: 6340206]

Maynard JE. Hepatitis B: global importance and need for control. Vaccine. 1990 Mar:8 Suppl():S18-20; discussion S21-3 [PubMed PMID: 2139281]

Klevens RM, Miller JT, Iqbal K, Thomas A, Rizzo EM, Hanson H, Sweet K, Phan Q, Cronquist A, Khudyakov Y, Xia GL, Spradling P. The evolving epidemiology of hepatitis a in the United States: incidence and molecular epidemiology from population-based surveillance, 2005-2007. Archives of internal medicine. 2010 Nov 8:170(20):1811-8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.401. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21059974]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRodriguez-Castro KI, Hevia-Urrutia FJ, Sturniolo GC. Wilson's disease: A review of what we have learned. World journal of hepatology. 2015 Dec 18:7(29):2859-70. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i29.2859. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26692151]

Patel D, McAllister SL, Teckman JH. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency liver disease. Translational gastroenterology and hepatology. 2021:6():23. doi: 10.21037/tgh.2020.02.23. Epub 2021 Apr 5 [PubMed PMID: 33824927]

Martin P, DiMartini A, Feng S, Brown R Jr, Fallon M. Evaluation for liver transplantation in adults: 2013 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Society of Transplantation. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 2014 Mar:59(3):1144-65 [PubMed PMID: 24716201]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFargo MV, Grogan SP, Saguil A. Evaluation of Jaundice in Adults. American family physician. 2017 Feb 1:95(3):164-168 [PubMed PMID: 28145671]

Ullrich D, Sieg A, Blume R, Bock KW, Schröter W, Bircher J. Normal pathways for glucuronidation, sulphation and oxidation of paracetamol in Gilbert's syndrome. European journal of clinical investigation. 1987 Jun:17(3):237-40 [PubMed PMID: 3113968]

VanWagner LB, Green RM. Evaluating elevated bilirubin levels in asymptomatic adults. JAMA. 2015 Feb 3:313(5):516-7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.12835. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25647209]

Bale G, Avanthi US, Padaki NR, Sharma M, Duvvur NR, Vishnubhotla VRK. Incidence and Risk of Gallstone Disease in Gilbert's Syndrome Patients in Indian Population. Journal of clinical and experimental hepatology. 2018 Dec:8(4):362-366. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2017.12.006. Epub 2017 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 30563996]