Introduction

Goiter simply refers to the enlargement of the thyroid gland. It can be due to various causes with the dietary iodine deficiency being the most common cause worldwide. In the United States, however, Graves disease and Hashimoto disease are the most commonly seen in clinical practice. The goiters have been classified in different categories, as per morphology (described as nodular versus diffuse), functional status (that could be hyperthyroid, hypothyroid, or euthyroid), the presence of malignancy, etc. By definition, a diffuse toxic goiter refers to a diffusely hyperplastic thyroid gland that is excessively overproducing the thyroid hormones. See Image. Toxic Nodular Goiter.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The following are potential commonly seen causes of a goiter development:

Epidemiology

The most common cause of diffuse toxic goiter is Graves disease. It is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism in the United States and worldwide affecting 1 in 200 people.

It usually affects people between 30 and 50 years of age, but can occur in any age group. It is 7 to 10 times more common in females than in males (see Image. Goiter in a Female). A marked increase in familial incidence has also been observed.

Pathophysiology

Diffuse toxic goiter consists of a diffusely enlarged, vascular gland with rubber-like consistency. Microscopically, the follicular cells are hypertrophic and hyperplastic with little colloid in them. Lymphocytes and plasma cells infiltrate into the gland and can ultimately aggregate into lymphoid follicles.

All cases of diffuse toxic goiter are not Graves disease and there may be various non-autoimmune causative processes although the majority of cases are autoimmune in nature. In Graves disease, antibodies are directed towards the thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSHr) which is present on thyroid follicular cells. The chronic stimulation of these receptors results in the production of excess amounts of T3 and T4 hormones and causes the enlargement of the thyroid gland that eventually results in a goiter.[6]

Histopathology

This disease has the following histological characteristics:[7]

- Diffuse non-nodular enlargement of the gland with a smooth capsule and increased vascularity.

- Hyperplasia of both follicular and papillary cells with lymphocytic infiltration into the stroma of the thyroid gland

- Follicular cells can also be enlarged and, in extreme cases, have enlarged nuclei mimicking that of papillary thyroid carcinoma. In Graves disease, however, they tend to maintain their rounded shape and have minimal clearing.

Due to the last point above, there have been controversies regarding the association between Graves disease and papillary thyroid carcinoma, and whether the coexistence of the two affects the prognosis. On systematic review of various studies, it has been seen that if a papillary carcinoma is discovered after surgical removal of the gland the prognosis is excellent, whereas when discovering a tumor in a patient with Graves disease, the local characteristics of the tumor (like the size, extent, margins, functionality, etc.) will most probably decide the final prognosis.[8]

History and Physical

History [9]

- Patients may present with a history of one or more consequences of a hyperthyroid state. These include weight loss, heat intolerance (with other heat-related symptoms like polydipsia, sweating), tremors, nervousness, anxiety, fatigue, palpitations, shortness of breath, frequent defecation or diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, etc.

- Patients may also complain of an obvious neck swelling or sensation of a lump in the neck, globus, swallowing difficulty, orthopnea, etc.

- Patients with Graves disease may present with additional features like:

- Ophthalmopathy known as Graves orbitopathy (seen in 25% of patients) that includes proptosis, diplopia, periorbital edema, excessive lacrimation, etc.

- Thyroid dermatopathy (more rare, only seen in 4% of patients and usually concurrent with orbitopathy) that presents with slightly thickened pigmented skin, especially over the pretibial area.

- Abnormalities of the reproductive system, most frequently presenting as irregular menstruation

Physical Examination

The most commonly described findings in a patient with the diffuse toxic goiter on physical exam are as follows:

- Constitutional: weight loss

- Head, eyes, ears, neck: neck swelling with occasional audible bruit, proptosis, lid lag, periorbital edema, exophthalmos

- Cardiovascular system: tachycardia, irregular heartbeat, systolic hypertension

- Neuromuscular: tremor of extremities, hyperreflexia, hyperactivity, muscle weakness

- Respiratory system: shortness of breath or tachypnea

- Skin and extremities: moist and warm skin, sweaty hands, pretibial myxedema

Evaluation

The primary evaluation of the toxic diffuse goiter consists of a complete thyroid profile, including serum T3, T4, and TSH levels.

- The serum TSH is the best screening test for evaluating thyroid hormone excess or deficiency.[10]

- In the case of diffuse toxic goiter, the above tests usually result in low or marginally low normal TSH levels with elevated peripheral serum thyroid hormone levels.

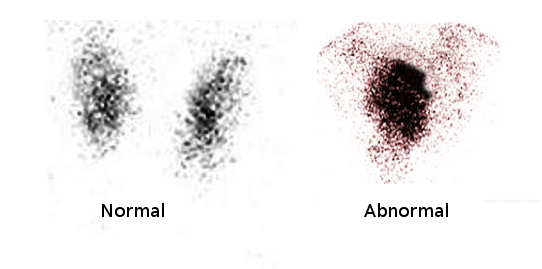

- Based on preferences in accordance with population characteristics, socioeconomic reasons, and cultural backgrounds, the modalities of evaluation of the cause of thyrotoxicosis can either be radioactive iodide uptake or a combination of thyroid ultrasound with TSH-receptor antibodies.[9]

- A high radioactive iodine uptake diffusely depicts Graves disease, as does an enlarged gland with positive TSH-receptor antibodies (TRAb).

Treatment / Management

The treatment modalities for diffuse toxic goiter include:

Antithyroidthyroid Drugs (ATD)[11]

- The antithyroid drug options are propylthiouracil, methimazole, and carbimazole.

- The American Thyroid Association (ATA) and American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE) recommend methimazole as the preferred drug for Graves disease, except in patients with adverse reactions to the drug or women in the first trimester of pregnancy. It is preferred over propylthiouracil due to better efficacy, longer half-life and duration of action, and the ease of using it as a once a day dosing.

- There are two different regimens to administer ATDs. The first is titration, where the dose of ATD is tapered to the lowest possible dose when the euthyroid state is achieved. The second regimen is based on block-and-replace method, where a high dose of ATD is given adjunct with thyroxine replacement to ultimately maintain a euthyroid state.[12]

- A drawback of ATD therapy is the risk of recurrence, especially in the first year after stopping therapy. Studies reported a 50% to 55% risk of recurrence, with poor prognostic factors pointing to this direction incuding severe hyperthyroidism, large goiter, high T3: T4 ratios, persistently suppressed TSH, and high baseline concentrations of TRAb.[13][14]

- Rare but major side effects of ATD therapy include agranulocytosis, hepatotoxicity, and vasculitis. (A1)

Radioactive Iodine Therapy (I-31, RAI)[13](A1)

- RAI is the commonest modality to treat Graves disease in the United States and it is a very safe and effective form of treatment.

- The absolute contraindications of this therapy include pregnancy, breastfeeding, and severe uncontrolled thyrotoxicosis.

- It can be administered in liquid or capsule forms, and fixed-dose therapy is as effective as calculated dose therapy based on the volume of the gland, iodine uptake, etc.

- Patients must discontinue all iodine-containing medication and be on iodine restricted diet to ensure effective uptake of RAI.

- ATD therapy needs to be discontinued preferably a week before the use of RAI and it can be resumed a few days after administering RAI, if needed.

- Potential side effects include the risk of developing hypothyroidism, and in rare occasions transient radiation-induced hyperthyroidism or worsening of thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy (TAO).

- While hypothyroidism is actively screened at subsequent follow-ups, prednisone can be used to prevent the progression of mild TAO.

- Patients have to be counseled about lifelong follow-up for either disease recurrence or for the development of hypothyroidism and they will benefit from prompt treatment if diagnosed with either abnormality.

Surgery

- Thyroidectomy is the most successful form of therapy for a diffuse toxic goiter, with total thyroidectomy being more successful than sub-total thyroidectomy with equivalent side effects.

- Due to the side effects associated with the use of general anesthesia, recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy, vascular complications, and hypothyroidism, surgical intervention is usually the last line of treatment.

- It is preferred in patients who are unable to tolerate antithyroid medications or RAI treatment, or in patients with compressive symptoms due to a bigger size of the goiter.[15] (B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Although diagnosed through the various forms of evaluation, as described in details above, the differential diagnosis of diffuse toxic goiter includes:

- Thyrotoxicosis factitia with over prescription or consumption of thyroid hormones

- Subacute or acute thyroiditis

- Multinodular goiter

- TSH secreting pituitary adenoma

- Iatrogenic iodine supplementation

Prognosis

Patients with diffuse toxic goiter, especially due to Graves disease, are expected to become hypothyroid during the natural course of their disease regardless of treatment. Prolonged thyrotoxicosis may cause ventricular thickening and, therefore, an increased risk of cardiac morbidity and mortality.

Treatment with RAI is done with the aim of permanent hypothyroidism, thus making the patient dependant on life long thyroid hormone supplementation. ATDs have an average remission rate of 50% but an excellent prognosis after 4 years, devoid of relapse.[16]

Complications

- Hyperthyroidism, or thyroid storm due to prolonged untreated excess of thyroid hormone

- Cardiac arrhythmias and congestive heart failure

- Rare liver pathology including fibrosis[17]

- Dermatopathy, mostly associated with Graves disease

- Graves ophthalmopathy

Consultations

Patients with diffuse goiters are advised to be evaluated by endocrinologists to undergo more detailed testing. Team work between primary care physicians, radiologists, surgeons and endocrine specialists should be coordinated for achieving better outcomes. Pharmacists should also counsel the patients on potential side effects of the medications used for their treatment, so they can be aware of the findings and report them to their doctors in a timely manner. Treatment approach steps should be discussed in advance and the patients should be provided with details of the expected advantages versus disadvantages of the different treatment choices. On several occasions, the physicians involved in the care of those patients will need to communicate closely to prepare the patients for the next steps to guarantee better compliance and results.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Diffuse toxic goiter may present with the usual hypermetabolic (like for example the heat intolerance, sweating, weight loss, etc.) and adrenergic symptoms (in particular the palpitations, tremors, emotional lability, etc.) of hyperthyroidism, along with the swelling of the goiter. On the other hand the elderly patients may not present with adrenergic symptoms, but rather with apathy, and atrial fibrillation, which might also be represents symptoms of depression, malignancy, or cardiac abnormalities.

Pearls and Other Issues

Although a lot of the cases of diffuse goiter remain asymptomatic, patients who notice any enlarged thyroid should be referred for specialty evaluation to investigate the function of the gland at the same time that the anatomy is looked at in more details. Blood tests focusing on the thyroid hormone levels and a neck ultrasound are the easiest starting points, and depending on their findings, further testing can be pursued as explained earlier.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Diagnosing diffuse toxic goiter is an amalgamation of clinical signs and investigations. Evaluating radiological and blood testings are important in reaching a conclusion to the underlying cause of the disease. Once diagnosed, it is the physician's responsibility to help the patient pick the best treatment option based on their profile, and with a thorough understanding of potential side effects. Women need to be especially careful and well informed as while being pregnant or breastfeeding they may require to change their form of therapy. Since this condition can also lead to cosmetic concerns (like the bulging of the neck or eventually the eyes,etc.) all physicians need to be sensitive and perceptive to them and counsel the patients about treatment options available, along with having a realistic approach to the treatment response.

Media

References

Zimmermann MB, Boelaert K. Iodine deficiency and thyroid disorders. The lancet. Diabetes & endocrinology. 2015 Apr:3(4):286-95. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70225-6. Epub 2015 Jan 13 [PubMed PMID: 25591468]

Swain M, Swain T, Mohanty BK. Autoimmune thyroid disorders-An update. Indian journal of clinical biochemistry : IJCB. 2005 Jan:20(1):9-17. doi: 10.1007/BF02893034. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23105486]

Knobel M. Etiopathology, clinical features, and treatment of diffuse and multinodular nontoxic goiters. Journal of endocrinological investigation. 2016 Apr:39(4):357-73. doi: 10.1007/s40618-015-0391-7. Epub 2015 Sep 21 [PubMed PMID: 26392367]

Dong BJ, How medications affect thyroid function. The Western journal of medicine. 2000 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 10693372]

Jereczek-Fossa BA, Alterio D, Jassem J, Gibelli B, Tradati N, Orecchia R. Radiotherapy-induced thyroid disorders. Cancer treatment reviews. 2004 Jun:30(4):369-84 [PubMed PMID: 15145511]

Prabhakar BS, Bahn RS, Smith TJ. Current perspective on the pathogenesis of Graves' disease and ophthalmopathy. Endocrine reviews. 2003 Dec:24(6):802-35 [PubMed PMID: 14671007]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLiVolsi VA, Baloch ZW. The Pathology of Hyperthyroidism. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2018:9():737. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00737. Epub 2018 Dec 3 [PubMed PMID: 30559722]

Oertli D,Harder F,Oberholzer M,Staub JJ, [Hyperthyroidism and thyroid carcinoma--coincidence or association?]. Schweizerische medizinische Wochenschrift. 1998 Nov 28; [PubMed PMID: 9879620]

De Leo S, Lee SY, Braverman LE. Hyperthyroidism. Lancet (London, England). 2016 Aug 27:388(10047):906-918. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00278-6. Epub 2016 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 27038492]

Baskin HJ, Cobin RH, Duick DS, Gharib H, Guttler RB, Kaplan MM, Segal RL, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for the evaluation and treatment of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Endocrine practice : official journal of the American College of Endocrinology and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. 2002 Nov-Dec:8(6):457-69 [PubMed PMID: 15260011]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChung JH. Antithyroid Drug Treatment in Graves' Disease. Endocrinology and metabolism (Seoul, Korea). 2021 Jun:36(3):491-499. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2021.1070. Epub 2021 Jun 16 [PubMed PMID: 34130446]

Allannic H,Fauchet R,Orgiazzi J,Madec AM,Genetet B,Lorcy Y,Le Guerrier AM,Delambre C,Derennes V, Antithyroid drugs and Graves' disease: a prospective randomized evaluation of the efficacy of treatment duration. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1990 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 1689737]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAbraham P, Avenell A, McGeoch SC, Clark LF, Bevan JS. Antithyroid drug regimen for treating Graves' hyperthyroidism. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2010 Jan 20:2010(1):CD003420. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003420.pub4. Epub 2010 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 20091544]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAzizi F, Abdi H, Amouzegar A, Habibi Moeini AS. Long-term thionamide antithyroid treatment of Graves' disease. Best practice & research. Clinical endocrinology & metabolism. 2023 Mar:37(2):101631. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2022.101631. Epub 2022 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 35440398]

Girgis CM, Champion BL, Wall JR. Current concepts in graves' disease. Therapeutic advances in endocrinology and metabolism. 2011 Jun:2(3):135-44. doi: 10.1177/2042018811408488. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23148179]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWiersinga WM. Graves' Disease: Can It Be Cured? Endocrinology and metabolism (Seoul, Korea). 2019 Mar:34(1):29-38. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2019.34.1.29. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30912336]

Lavruk KZ,Dudiy PF,Skrypnyk NV,Mishchuk VH,Vytvytskiy ZY, Clinical-laboratory and ultrasound parallels of changes in the liver and thyroid gland in diffuse toxic goiter. Journal of medicine and life. 2022 Jan [PubMed PMID: 35186140]