Introduction

Hairy leukoplakia (HL) was first described in 1984 and is a disease of the mucosa.[1] It is associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), also known as human herpesvirus 4. It occurs most commonly in people infected with HIV, although it can also be seen in people who do not have HIV. Such patients usually have had an organ or bone marrow transplant or some immunocompromised disease or hematological malignancy.[2]

However, it has also been reported in individuals who are not immunocompromised.[3] Such immunocompetent patients have shown to be on inhaled, topical, or systemic corticosteroids for the long term, which occur as a risk factor for developing the condition.[4] The Centre for Disease Control and Prevention has classified this condition as a Category-B clinical marker of HIV disease since it has a clear prognostic value in the subsequent development of AIDS.[5]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Hairy leukoplakia is commonly found in association with HIV infection and/or immunosuppression. It has been observed that the risk of developing hairy leukoplakia increases almost two times with every 300-unit decrease in the CD4 count. It has also been seen in patients with other forms of severe immunodeficiencies, such as those on chemotherapy or who have had an organ transplant or leukemia. It has rarely been seen in immunocompetent patients.

Moreover, hairy leukoplakia has also been seen associated with Behcet syndrome and ulcerative colitis. In HIV-positive men, smoking more than a pack of cigarettes/day has been correlated positively with the development of hairy leukoplakia.

Epidemiology

Hairy leukoplakia is commonly found in HIV-positive homosexual men, particularly those who smoke. Studies have shown that HL can occur in up to 50% of patients who are not under any treatment for HIV, especially in those patients in whom CD4 count has reached less than 0.3 × 10/L. No racial or age predilection has been observed for hairy leukoplakia.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of this condition is complex, requiring an interplay of various factors such as EBV coinfection along with its productive replication, virulence, genetic evolution in association with expressing specific EBV genes that are in a latent state. All these factors enhanced by local as well as systemic deficiency of the host immune system lead to hairy leucoplakia.[6] The virus infects the basal cells of the epithelium in the pharynx initially. Here it enters into a replicative state that releases the infectious virus into the saliva. This process continues throughout the lifespan of the infected person. In the pharynx, the virus may also enter the B cells, where it stays for an indefinite duration and in a latent state. Although the elimination of EBV from the body is not possible with the cytotoxic T lymphocytes, they are still required for maintaining the infection in its latent state. The latent virus in B lymphocytes on reactivation produces virions. The release of these virions infects the circulating monocytes, which then migrate to the lamina propria of the mucosa of the oral cavity and subsequently differentiate into macrophages and precursors of the Langerhans cell. These then migrate into the oral epithelium, where they lie majorly in the basal and /or the parabasal layer. Upon reactivation of the virus, it migrates to the keratinocytes in the spinosum and granulosum layer via the dendritic processes of the Langerhans cells. Upon reaching these layers, the virus starts replicating.

Moreover, a marked reduction or an absence of Langerhans cells (antigen-presenting immune cells necessary for the response of the immune system to the viral infection) has also been found in hairy leukoplakia biopsy tissues.[7][8] Their deficiency may allow EBV to replicate persistently and escape immune recognition.

Since the lateral border of the tongue is more susceptible to mechanical trauma, access to EBV to the prickle cell receptors is easy. Impaired immune status of the host along with a marked reduction of Langerhans cells. then contribute to the successful establishment of EBV in the oral epithelium.[7]

Histopathology

The histopathological picture of the condition shows five major features:[9][10]

- Hyperkeratosis of the superficial layer of the epithelium: This is due to alteration in the pattern of expression of keratin in the squamous cells of the epithelium. This hyperkeratotic thick layer may separate from the underlying cells, resulting in projections producing the typical "hairy" appearance of the lesion. This hyper-keratinized epithelium may get superficially infected with bacteria and/or Candida.

- Hyperparakeratosis of the superficial layer of the epithelium: The abnormal persistence of nuclei of the cell in this layer of the epithelium represents incomplete squamous differentiation. This layer may show the presence of numerous Candida hyphae.

- Acanthosis of the upper stratum spinosum/prickle cell layer: This abnormal expansion of cells occurs with layers of koilocyte-like cells or ballooned cells. The nuclei may show a ground-glass appearance throughout and may contain eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions with a halo (Cowdry type A).

- Absence of inflammation in the epithelium and minimal to zero inflammation in the lamina propria, and even absent inflammatory mononuclear cells infiltrate.

- Normal basal cells of the epithelium histologically: The gene BZLF1 is required to bring about the intracellular transition from the latent state to the productive infectious state. In hairy leukoplakia, the BZLF1 gene is restricted to the .cells of the stratum spinosum and stratum granulosum. The cells of these layers express the gene Blimp1, which acts as a transcription factor during the terminal differentiation of keratinocytes. Both Blimp1 and BZLF1 cannot be detected in the basal cell layer of the oral epithelium, due to which it is assumed that the basal cell layer is not involved in hairy leukoplakia.

Although the above features indicate hairy leukoplakia, none of the above histologic features is typical and found only in this lesion. Therefore, the definitive diagnosis of hairy leukoplakia requires histologic appearance along with the demonstration of DNA, RNA, or protein of Epstein-Barr virus within the epithelial cells.

History and Physical

History

Hairy leukoplakia is often asymptomatic, due to which many patients are unaware of its presence. They may report a non-tender whitish plaque along the lateral border of the tongue. The lesion may appear and disappear spontaneously. Some patients may experience mild pain, dysesthesia, altered sensitivity to food temperature, alteration in the taste sensation due to alteration in taste buds, and the psychological impact of its unsightly cosmetic appearance.

Physical Examination

Intraorally, unilateral or bilateral non-painful white lesions are seen mostly on the lateral margin of the tongue.[11] The lesion may vary in appearance from a smooth, flat, and small lesion to an irregular "hairy" or "feathery" lesion with prominent folds or projections. It may occur as either a continuous or discontinuous lesion along the lateral border of the tongue and is often not symmetrical bilaterally. The lesions may vary in size, severity, and surface characteristics.[10] The lesion is adherent to the surface and cannot be removed by scraping. The surrounding tissue does not show any sign of erythematous or edematous change. Hairy leukoplakia may also involve other surfaces f the tongue, the buccal mucosa, and/or the gingiva. Here, it may appear flat with a smooth surface, thus, lacking the typical "hairy" appearance of the lesion.

Evaluation

Generally, the diagnosis of hairy leukoplakia is established on a clinical basis. Still, the definitive diagnosis requires histological examination and the demonstration of DNA, RNA, or protein of the Epstein-Barr virus within the epithelial cells. For this purpose, several kits are commercially available.[12] Various techniques can be employed to detect EBV, such as polymerase chain reaction, electron microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and in situ hybridization. Among all these techniques, in situ hybridization is considered to be the gold standard. A tissue biopsy can be done, but it is indicated only if the lesion shows an unusual appearance or is ulcerated suggestive of cancer.[13]

Treatment / Management

As hairy leukoplakia is a benign condition with a low morbidity rate and a tendency to resolve spontaneously, every case does not need to be specifically treated. Treatment is given for providing relief for symptoms caused by the condition or when the patient wishes to treat the condition for esthetic reasons. Treatment options include anti-retroviral drugs. Highly active antiretroviral therapy drugs usually reduce hairy leukoplakia, but the condition may reoccur when the drug dosage is reduced.[14]

Systemic management using antiviral drugs usually resolves the condition within 7 to 14 days of treatment. Oral treatment with antiviral medication such as acyclovir needs to be given in a high dosage of about 4000 mg per day in divided dosages for at least seven days to achieve the required therapeutic levels.[15] Other drugs, such as valacyclovir and famciclovir, can also be used. These are new antiviral drugs with relatively higher bioavailability than the drug acyclovir orally and require relatively lesser dosage. They are used in the dosage of 3000 mg and 1500 mg per day in divided dosages. The mechanism of action of these drugs is to inhibit the replication of productive EBV, but they do not eradicate the latent infection. But the disadvantage is that the condition often recurs a few weeks after the cessation of these drugs.

Topical treatment can be done using podophyllin resin. This resin solution is used in a concentration of 25% that usually resolves the condition after a few applications.[16] Podophyllin has cytotoxic effects on the cells, but its exact mechanism in resolving the condition is not yet known. But, as with other drugs, this treatment also has chances of reoccurrence after cessation. Also, the treatment may temporarily result in pain and discomfort in the areas of application and dysgeusia.[17] (A1)

Retinoic acid can also be used for topical treatment. Tretinoin (e.g., 0.1% vitamin A) is generally applied two or three times a day until the patches have disappeared. Retinoic acids inhibit the replication of the virus. However, the condition recurs several weeks after being successfully treated with retinoic acid.

Cryotherapy (liquid nitrogen) has also been reported to resolve hairy leukoplakia but is not a widely used treatment modality.[18](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses of hairy leukoplakia include:[19]

- Candidiasis

- Oral leukoplakia

- White sponge nevus

- Oral frictional keratosis

- Smoker’s keratosis

- Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia

- Lichen planus

- Lichenoid reactions

- Condyloma acuminatum

Prognosis

Most of the patients presenting tend to have significant suppression of the immune system when diagnosed with hairy leukoplakia. The condition occurs relatively soon after seroconversion of HIV, i.e., before AIDS. The CD4 count on an average when the condition is first detected may range from 235-468/microL. Studies have found that patients with AIDS in association with hairy leukoplakia have a shorter lifespan than those who do not show signs of this lesion. Moreover, if these patients get co-infected with the hepatitis B virus, their condition may worsen, resulting in early progression to AIDS.

Complications

Hairy leukoplakia may be complicated by an occasional candidal superinfection, resulting in glossopyrosis (burning tongue). The altered taste sensation is another but rare complication. The topical retinoids, when used for a prolonged duration, may lead to a burning sensation.

Deterrence and Patient Education

The presence of oral lesions has a significant impact on the health-related quality of life of the patient due to altered speech, difficulty in mastication and deglutition, and/or pain. This might exacerbate nutrition-associated problems that further deteriorate the health of the patient. Thus, patients should be provided with the proper knowledge of HIV-associated oral lesions and oral health.

Prevention of hairy leukoplakia starts with having a healthy immune system. Patients should be educated to follow the prescribed HIV treatment plan and dental hygiene routine. Also, steps should be taken to maintain a healthy lifestyle. As people with HIV who have the habit of smoking are also at a greater risk of getting it in comparison to those who do not smoke, the patient should be educated in this regard.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The treatment outcome, in general, can be enhanced if the dentists have thorough knowledge about the treatment of oral conditions related to HIV infection, such as hairy leukoplakia. Based on the patient’s history, physical and laboratory findings, the dentist and his interprofessional health care team should formulate a plan of adequate follow-up care. The role of health care professionals goes beyond basic education and training. It extends to providing proper knowledge and information to the patients regarding oral lesions along with the development of reinforcing educational programs as early diagnosis and management of these lesions play a vital role in reducing the impact of the disease on the patient. Specialty trained nurses in AIDS and otolaryngology educate patients, arrange for follow-up, and facilitate communication among the team. Pharmacists consult with clinicians to determine the appropriate agent(s) and dosing, review prescriptions, check for interactions and inform patients. These interprofessional interventions will improve patient outcomes.[Level 5]

Media

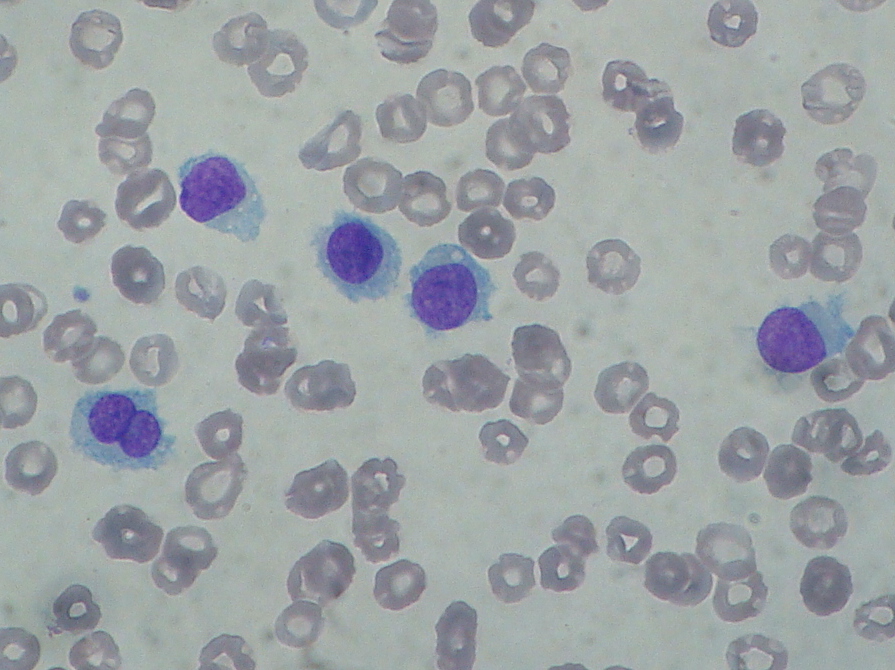

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Hairy cell leukemia: abnormal B cells look "hairy" under a microscope because of radial projections from their surface. This picture is a contribution of Paulo Henrique Orlandi Mourao and is licensed to be shared under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en). The picture is obtained from the following link (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hairy_cell_leukemia_smear_2009-08-20.JPG)

References

Kreuter A, Wieland U. Oral hairy leukoplakia: a clinical indicator of immunosuppression. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2011 May 17:183(8):932. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100841. Epub 2011 Mar 7 [PubMed PMID: 21398239]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKhammissa RA, Fourie J, Chandran R, Lemmer J, Feller L. Epstein-Barr Virus and Its Association with Oral Hairy Leukoplakia: A Short Review. International journal of dentistry. 2016:2016():4941783. doi: 10.1155/2016/4941783. Epub 2016 Mar 7 [PubMed PMID: 27047546]

Darling MR, Alkhasawneh M, Mascarenhas W, Chirila A, Copete M. Oral Hairy Leukoplakia in Patients With No Evidence of Immunosuppression: A Case Series and Review of the Literature. Journal (Canadian Dental Association). 2018 May:84():i4 [PubMed PMID: 31199724]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePiperi E, Omlie J, Koutlas IG, Pambuccian S. Oral hairy leukoplakia in HIV-negative patients: report of 10 cases. International journal of surgical pathology. 2010 Jun:18(3):177-83. doi: 10.1177/1066896908327865. Epub 2008 Nov 25 [PubMed PMID: 19033322]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence. 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR. Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and reports. 1992 Dec 18:41(RR-17):1-19 [PubMed PMID: 1361652]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSachithanandham J, Kannangai R, Pulimood SA, Desai A, Abraham AM, Abraham OC, Ravi V, Samuel P, Sridharan G. Significance of Epstein-Barr virus (HHV-4) and CMV (HHV-5) infection among subtype-C human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals. Indian journal of medical microbiology. 2014 Jul-Sep:32(3):261-9. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.136558. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25008818]

Daniels TE, Greenspan D, Greenspan JS, Lennette E, Schiødt M, Petersen V, de Souza Y. Absence of Langerhans cells in oral hairy leukoplakia, an AIDS-associated lesion. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 1987 Aug:89(2):178-82 [PubMed PMID: 3110300]

Gondak RO, Alves DB, Silva LF, Mauad T, Vargas PA. Depletion of Langerhans cells in the tongue from patients with advanced-stage acquired immune deficiency syndrome: relation to opportunistic infections. Histopathology. 2012 Feb:60(3):497-503. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.04068.x. Epub 2011 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 22168427]

Dias EP, Spyrides KS, Silva Júnior AS, Rocha ML, da Fonseca EC. [Oral hairy leukoplakia: histopathologic features of subclinical stage]. Pesquisa odontologica brasileira = Brazilian oral research. 2001 Apr-Jun:15(2):104-11 [PubMed PMID: 11705191]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSoutham JC, Felix DH, Wray D, Cubie HA. Hairy leukoplakia--a histological study. Histopathology. 1991 Jul:19(1):63-7 [PubMed PMID: 1655610]

Jones KB, Jordan R. White lesions in the oral cavity: clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Seminars in cutaneous medicine and surgery. 2015 Dec:34(4):161-70. doi: 10.12788/j.sder.2015.0180. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26650693]

De Souza YG, Freese UK, Greenspan D, Greenspan JS. Diagnosis of Epstein-Barr virus infection in hairy leukoplakia by using nucleic acid hybridization and noninvasive techniques. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1990 Dec:28(12):2775-8 [PubMed PMID: 2177752]

Martins LL, Rosseto JHF, Andrade NS, Franco JB, Braz-Silva PH, Ortega KL. Diagnosis of Oral Hairy Leukoplakia: The Importance of EBV In Situ Hybridization. International journal of dentistry. 2017:2017():3457479. doi: 10.1155/2017/3457479. Epub 2017 Jul 17 [PubMed PMID: 28798771]

Greenspan JS, Greenspan D, Webster-Cyriaque J. Hairy leukoplakia; lessons learned: 30-plus years. Oral diseases. 2016 Apr:22 Suppl 1():120-7. doi: 10.1111/odi.12393. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27109280]

Resnick L, Herbst JS, Ablashi DV, Atherton S, Frank B, Rosen L, Horwitz SN. Regression of oral hairy leukoplakia after orally administered acyclovir therapy. JAMA. 1988 Jan 15:259(3):384-8 [PubMed PMID: 2826830]

Gowdey G, Lee RK, Carpenter WM. Treatment of HIV-related hairy leukoplakia with podophyllum resin 25% solution. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics. 1995 Jan:79(1):64-7 [PubMed PMID: 7614164]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBrasileiro CB, Abreu MH, Mesquita RA. Critical review of topical management of oral hairy leukoplakia. World journal of clinical cases. 2014 Jul 16:2(7):253-6. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i7.253. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25032199]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGoh BT, Lau RK. Treatment of AIDS-associated oral hairy leukoplakia with cryotherapy. International journal of STD & AIDS. 1994 Jan-Feb:5(1):60-2 [PubMed PMID: 8142532]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTriantos D, Porter SR, Scully C, Teo CG. Oral hairy leukoplakia: clinicopathologic features, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and clinical significance. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 1997 Dec:25(6):1392-6 [PubMed PMID: 9431384]