Introduction

Hemarthrosis is bleeding into a joint cavity. Its presence can be suspected based upon patient history, physical exam, and multiple imaging modalities; however, the best way to diagnose hemarthrosis is with arthrocentesis with synovial fluid analysis. Lipohemarthrosis the presence of fat and blood in the joint cavity.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Many diseases and disorders can present with hemarthrosis. However, categorization is generally divided into traumatic, non-traumatic, and postoperative. Traumatic injury is the most common cause of hemarthrosis.

Non-traumatic hemarthrosis can be caused by a variety of bleeding disorders that are either hereditary or acquired. Hereditary bleeding disorders include hemophilia and other inherited coagulation factor deficiency disorders. Examples of acquired bleeding disorders include advanced liver or renal disease, vitamin K deficiency, disseminated intravascular coagulation, or anticoagulation medication use. Other more rare causes of non-traumatic hemarthrosis include the following:

- Neurologic: Reflex sympathetic dystrophy, diabetic neuropathic arthropathy

- Infectious: Septic bacterial arthritis

- Vascular: Vitamin C deficiency, ruptured peripheral artery aneurysms, osteoarthritis (degenerative tears of peripheral arteries associated with a posterior horn of the lateral meniscus)

- Neoplasms: Benign synovial hemangiomas, pigmented villonodular synovitis, or any malignant tumor arising near a joint cavity or metastatic[1][2]

Post-operative recurrent hemarthrosis is frequently associated with total knee arthroplasty and has also been described as an uncommon complication following arthroscopy.[3]

Epidemiology

The exact prevalence of hemarthrosis in the hemophiliac population is unknown; however, there have been reports that approximately 50% will develop hemarthrosis at some time during their life. Joint trauma increases the chance of developing hemarthrosis in this population.[4] Based on a cohort study of 1145 consecutive patients who developed a traumatic hemarthrosis of the knee, approximately half had an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury, and the annual incidence of ACL injury was 77 per 100,000 inhabitants with a significant difference between men (91 per 100,000) versus women (63 per 100,000). In those 16 years of age or younger, lateral patellar dislocation was the most frequent structural injury associated with traumatic hemarthrosis of the knee both in boys (39%) and girls (43%); in this age group, the annual incidence of lateral patellar dislocation was 88 per 100,000 and higher in boys (113 per 100,000) than girls (62 per 100,000).[5]

Pathophysiology

Traumatic hemarthrosis typically occurs in the setting of intra-articular injury with ligamentous, osseous, and/or cartilage damage leading to a bloody synovial fluid collection. Post-operative hemarthrosis from total knee arthroplasty has been attributed to the development of intra-capsular vascular tissue which subsequently causes bleeding into the joint after joint replacement surgery. The development of a lipohemarthrosis stems from marrowfat leakage into the synovial fluid; this is usually the result of intra-capsular fractures or extensive intra-articular soft tissue injury.[6]

Histopathology

The histopathology of hemophilic arthropathy can be divided into early and late disease characteristics. In early disease, there is synovial hypertrophy and fibrosis which displays changes similar to rheumatoid arthritis. Progression of the disease shows disruption of cartilage and subchondral cyst formation from interosseous bleeding. The intra-articular bleeding has direct toxic effects leading to the destruction of cartilage and bone. Iron in the form of ferric citrate stimulates human fibroblast cells to proliferate. Studies involving mice imply hemarthrosis leads to blood vessel hyperplasia which may explain the predisposition for hemophiliacs to experience recurrent intra-articular bleeding.[7][8]

Toxicokinetics

Rodenticides are superwarfarins that, upon ingestion, can cause spontaneous bleeding including acute hemarthrosis. Patients can be asymptomatic up to 72 hours after ingestion. Gastrointestinal symptoms can be present early in the course of poisoning, and spontaneous bleeding can present as early as 8 hours after exposure.

History and Physical

In most patients, especially those without pre-existing neurologic sensation dysfunction or bleeding disorders, a traumatic incident is known to the patient, and the cause of the hemarthrosis is suggestive from history. Following an injury with intra-articular damage, the swelling from bloody synovial fluid accumulation is typically rapid within a few hours. Pain is a significant component, however, may take time to develop, or may be minimal or absent in patients with pre-existing impaired sensation. The range of motion of the affected joint is typically significantly reduced.

Certain locations and types of injury following a traumatic incident are more likely to develop a hemarthrosis. Intra-articular elbow fractures including those of the radial head are universally associated with hemarthrosis. The knee is a frequent site of hemarthrosis with the most common mechanism being forced twisting of the loaded joint. The majority of these post-traumatic hemarthroses are from ligamentous and meniscal damage. Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears are the most common, representing 70% of post-traumatic hemarthrosis of the knee, followed by 10% to 15% patellar subluxation/dislocation injuries, 10% from meniscal tear, 2% to 5% from osteochondral fracture fragments, and 5% represented from other injuries including posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) or capsule tears. Depending on the site and kind of injury, tenderness to palpation of the joint lines or patella will be present and clinical tests for joint laxity may be positive.[9]

Lipohemarthrosis indicates either a fracture with intra-articular extension or significant intra-articular soft tissue injury (ligamentous or meniscal). If a lipohemarthrosis of the knee is identified, suspect in order of likelihood: tibial plateau fracture (lateral plateau fractures often associated with ACL and MCL injuries), tibial spine avulsion (anterior attachment point of ACL and more common in pediatric patients who have tougher ligaments than bones), and femoral condyle fracture (uncommon, however, associated with popliteal artery and fibular nerve injury).

If hemarthrosis occurs spontaneously or after minimal trauma, bleeding disorders such as hemophilia should be suspected. Hemarthrosis is the most common musculoskeletal manifestation of hemophilia. Severe hemophilia (less than 1% of normal factor activity) causes hemarthrosis in 75% to 90% of patients with the first attack typically occurring between ages 2 to 3. Any joint can be affected; however, the knee is the most common site. Patient history regarding family history, extensive or prolonged bleeding during or after surgery, use of anticoagulant medications, and diet habits should be elicited to help determine whether the presence of a bleeding diathesis exists.[10]

Clinical presentation of hemophilia with hemarthrosis can vary by age. In adults and older children, there is typically a prodromal stiffness or tingling which precedes pain and swelling. In infants, signs of hemarthrosis may include irritability and decreased use of the affected limb. Bleeding into the hip joint is concerning due to the greater risk of increased intra-articular pressure and osteonecrosis of the femoral head. In hemophilic hemarthrosis, one joint is typically affected at a time; however, bilateral joint involvement is possible.[11][10]

Evaluation

A suspected hemarthrosis can be evaluated by plain radiographs, computed tomography (CT) scan, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The preferred initial imaging modality is plain film radiology of the involved joint and surrounding bones. If a fracture is not seen but strongly suspected, further evaluation with a CT scan is warranted. MRI may be able to diagnose ligamentous or other soft tissue injuries as the cause of hemarthrosis. Ultrasound (US) in the right clinical setting can help identify and characterize intra-articular fluid collections.[12]

Arthrocentesis and joint aspirate fluid analysis may be required for definitive diagnosis. The synovial fluid from a hemarthrosis may appear red, pink, or brown depending on the cause of bleeding. Aspiration of the joint and subsequent analysis can differentiate simple effusion, hemarthrosis, lipohemarthrosis, and septic arthritis. Arthrocentesis can also provide significant relief of pain for the patient. The presence of lipid globules in the aspirate represents a lipohemarthrosis. If the initial synovial fluid aspirate is non-bloody but bright red blood soon appears after withdrawing fluid, then this is indicative of a traumatic hemarthrosis. A true hemarthrosis typically does not clot due to fibrinolysis compared to a bloody aspirate from traumatic aspiration that does coagulate. Centrifugation of the synovial fluid aspirate and examination of the supernatant may also be helpful to discern the difference between true hemarthrosis and traumatic aspiration; a true hemarthrosis will display a serous appearance of the synovial fluid supernatant with xanthochromia.[13]

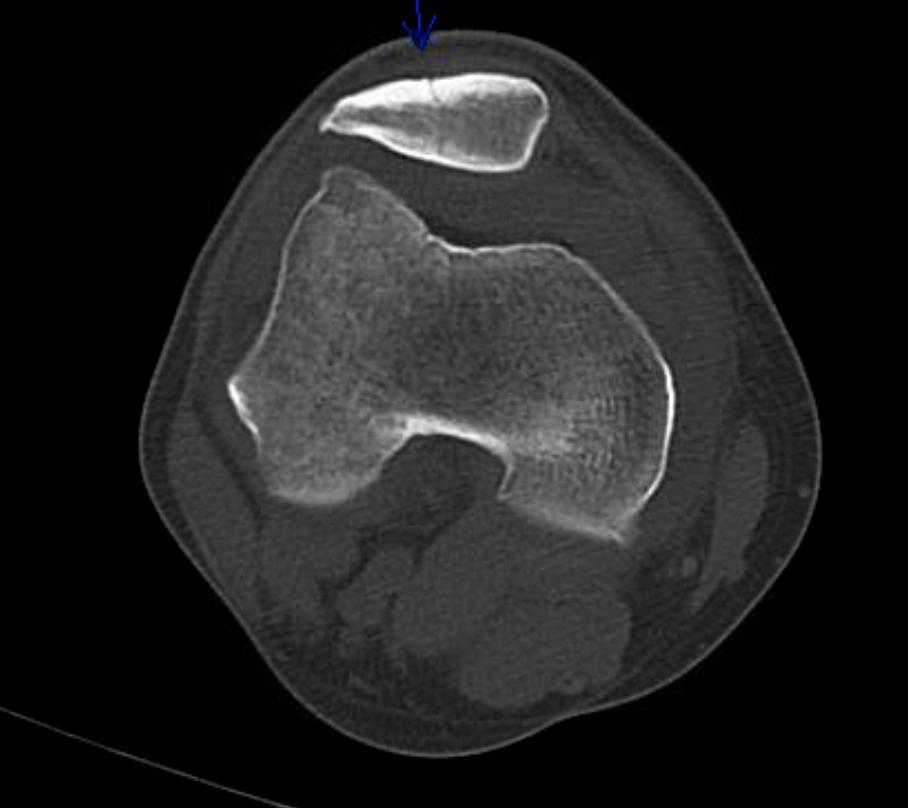

Lipohemarthrosis can be detected by arthrocentesis, plain radiographs, CT scan, MRI, and in a minority of patients by US. The presence of a linear interface between 2 different densities with an effusion suggests lipohemarthrosis. This feature results from the entry of marrow fat into the joint cavity and is highly suggestive of an intra-articular fracture. One series demonstrated that 65% of patients with intra-articular fracture did not have fat-fluid levels on plain radiographs; however, all patients with lipohemarthrosis visible on plain radiographs were found to have intra-articular fractures. On plain radiographs the finding of a single fluid-fluid level (layering of fat and blood) on a cross-table view is suggestive of a lipohemarthrosis; however, it can occur without the presence of fat globules. The finding of a double fluid-fluid level (layering fat, blood, and serum) is specific for lipohemarthrosis and can be seen on either US or CT or MRI scans. The sonographic finding of lipohemarthrosis may be used as a sensitive surrogate marker for intra-articular fracture. When used alone for evaluation of acute knee trauma, plain radiographs can miss up to 21% of fractures. If a lipohemarthrosis is identified on either plain film or US, there should be a high suspicion for an occult fracture which should prompt further evaluation with CT scan.[14][15]

See Figure 1, a horizontal, cross-table lateral view plain radiograph of the knee with a fat fluid level in the supra-patellar recess compatible with a lipohemarthrosis.

Treatment / Management

Treatment of hemarthrosis includes interventions that are helpful for any patient who develops acute hemarthrosis for any reason along with specific treatments that target the underlying cause of the hemarthrosis. Initial treatment of any acute hemarthrosis includes immobilization, ice, and compression. Analgesia for pain control may be required in the acute period, especially to obtain a radiographic evaluation. Arthrocentesis with aspiration from a joint can be both diagnostic and therapeutic by reducing pressure from the effusion.[16]

In patients receiving therapeutic anticoagulation, clinically significant hemarthrosis is rare. These patients typically tolerate arthrocentesis. In the rare event, these patients develop persistent or recurrent hemarthrosis, repletion of clotting factors with fresh frozen plasma or reversal of anticoagulation with the appropriate pharmacologic agent could be considered. In patients with recurrent postoperative hemarthrosis, revision angioplasty may be necessary. For the cases of ruptured aneurysms, vascular surgery intervention or arterial embolization may be warranted. For benign tumors, arthroscopic or surgical synovectomy is the treatment of choice to prevent recurrent episodes of hemarthrosis.

Special treatment considerations should be given for hemophiliacs presenting with acute hemarthrosis. Coagulation factor specific to hemophilia should be infused promptly at the first sign of joint bleeding (including the prodromal stiffness or tingling phase prior to pain and swelling) ideally within 2 hours of bleed identification. For bleeding into the hip, a target joint, or bleeding associated with trauma, higher factor activity levels of 80% to 100% are targeted; for hemophilia A give 50 units/kg of factor VIII and for hemophilia B given 100 to 120 units/kg of factor IX. For hemarthrosis in peripheral joints such as knees, elbows, or ankles, the factor activity level should be raised to at least 40% to 50%; for hemophilia A give 25 units/kg of factor VIII and for hemophilia B give 50 to 60 units/kg of factor IX. Medications with anti-platelet activity such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs) should be avoided. Arthrocentesis is not necessary to diagnose joint bleeding in patients with known hemophilia; however, if arthrocentesis is deemed necessary to rule out a septic joint or reduce pressure from accumulated blood, it should only be performed after the factor has been infused to raise the specific factor levels. In hemophiliacs with target joints who undergo repeated hemorrhage, a short course of glucocorticoids has been found beneficial to reduce pain and swelling associated with synovial inflammation, as long as no signs of septic arthritis exist. Joint surgery for chronic synovitis or arthropathy may be indicated including synovectomy for recurrent bleeding or joint replacement for extensive joint damage.[17][18](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of an acute joint effusion includes other notable disease processes. Conditions which can be mistaken for an acute hemarthrosis include:

- Septic arthritis

- Lyme disease

- Tuberculosis

- Gout (monosodium urate crystals)

- Pseudogout (calcium pyrophosphate crystals)

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Leukemia

- Seronegative spondyloarthropathies (psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease arthritis)

- Osteoarthritis

This may be especially true if associated with trauma is remote, unclear, or unknown. Arthrocentesis with synovial fluid analysis, diagnostic imaging, and further laboratory workup specific to these other disease processes may be required to differentiate between the causes of an acute joint effusion.

Prognosis

The acute swelling and pain of a hemarthrosis with proper treatment, including arthrocentesis when indicated, can be significantly reduced over the course of days; however, it may take several weeks to resolve completely. In the event the hemarthrosis was caused by an intra-articular fracture or significant soft tissue injury, orthopedic surgery may be warranted for these individuals. Following the resolution of a hemarthrosis, a rehabilitation program to increase the range of motion, weight-bearing, and joint strength is indicated. A physical therapist with expertise in hemophilia is ideal for this specific patient population.[11]

Complications

Severe or recurrent hemarthrosis can lead to the destruction of intra-articular cartilage and degenerative arthritis. The toxic effects of blood cause intra-articular damage leading to synovial hypertrophy and fibrosis. In hemophiliacs, these joints which undergo chronic inflammatory changes from repetitive attacks of hemarthrosis are called “target joints.” Repeated or prolonged attacks can lead to chronic disabling arthropathy due to internal joint derangement and impaired joint movement. Chronic arthropathy affects approximately 20% of hemophiliacs. Recurrent hemarthrosis in hemophiliacs can be prevented with the administration of prophylactic coagulation factors.[6][11]

Consultations

In the setting of an acute hemarthrosis, if there is evidence or high suspicion of an intra-articular fracture or soft tissue injury (ligamentous, capsule, meniscal tear), orthopedic consultation should be considered. Although not all intra-articular fractures or soft tissue injuries require operative intervention, the patient's case including radiographic findings should be discussed with an orthopedic surgeon.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The lifelong management of hemophilia including the treatment and prevention of hemarthrosis and disabling arthropathy takes an interprofessional approach. The World Federation of Hemophilia has published guidelines for the management of hemophilia based on an extensive literature review. The interprofessional approach encourages treatment contributions from all areas of medicine including physical therapists, hematologists, physiologists, and orthopedic surgeons. Physical therapy promotes physical fitness and normal neuromuscular development with specific attention to muscle strengthening, coordination, physical functioning, healthy body weight, and self-esteem.[19] (Level II) For patients with significant musculoskeletal dysfunction, weight-bearing activities promote the development and maintenance of bone density.[20][21] (Level III)

The primary aim is to prevent and treat bleeding with the deficient clotting factor. The specific factor deficiency should be treated with specific factor concentrate. Acute bleeds should be treated as soon as possible, ideally within 2 hours. (Level IV). Arthrocentesis should be performed when the hemarthrosis is tense, painful, and shows no improvement after 24 hours of conservative treatment or when there is a neurovascular compromise of the limb from hemarthrosis or evidence of infection.[22][23][24] (Level III)

Synovectomy should be performed if chronic synovitis persists along with frequent recurrent bleeding which is not controlled by other measures. Options for synovectomy include chemical, radioisotopic, arthroscopic, or open surgical synovectomy.[25] (Level IV) Non-surgical synovectomy is the choice procedure; radioisotopic synovectomy using a pure beta emitter, such as phosphorus-32 or yttrium-90, is highly effective, has few side effects, and can be accomplished in an outpatient setting.[26][27] (Level IV)

Pain should be controlled with appropriate analgesics such as COX-2 inhibitors.[28][29] (Level II)

If conservative measures fail to relieve pain and improve joint function, surgical intervention may be considered. A patient with hemophilia and requiring surgery should be managed at a comprehensive hemophilia treatment center including an anesthesiologist that has experience treating patients with bleeding disorders.[30][31] (Level III)

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Baker CL. Acute hemarthrosis of the knee. Journal of the Medical Association of Georgia. 1992 Jun:81(6):301-5 [PubMed PMID: 1607844]

Kawamura H, Ogata K, Miura H, Arizono T, Sugioka Y. Spontaneous hemarthrosis of the knee in the elderly: etiology and treatment. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 1994 Apr:10(2):171-5 [PubMed PMID: 8003144]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWorland RL, Jessup DE. Recurrent hemarthrosis after total knee arthroplasty. The Journal of arthroplasty. 1996 Dec:11(8):977-8 [PubMed PMID: 8986579]

Manners PJ, Price P, Buurman D, Lewin B, Smith B, Cole CH. Joint Aspiration for Acute Hemarthrosis in Children Receiving Factor VIII Prophylaxis for Severe Hemophilia: 11-year Safety Data. The Journal of rheumatology. 2015 May:42(5):885-90. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141236. Epub 2015 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 25729030]

Olsson O, Isacsson A, Englund M, Frobell RB. Epidemiology of intra- and peri-articular structural injuries in traumatic knee joint hemarthrosis - data from 1145 consecutive knees with subacute MRI. Osteoarthritis and cartilage. 2016 Nov:24(11):1890-1897. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2016.06.006. Epub 2016 Jun 29 [PubMed PMID: 27374877]

Roosendaal G, Vianen ME, Marx JJ, van den Berg HM, Lafeber FP, Bijlsma JW. Blood-induced joint damage: a human in vitro study. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1999 May:42(5):1025-32 [PubMed PMID: 10323460]

Wen FQ, Jabbar AA, Chen YX, Kazarian T, Patel DA, Valentino LA. c-myc proto-oncogene expression in hemophilic synovitis: in vitro studies of the effects of iron and ceramide. Blood. 2002 Aug 1:100(3):912-6 [PubMed PMID: 12130502]

Rodriguez-Merchan EC. The destructive capabilities of the synovium in the haemophilic joint. Haemophilia : the official journal of the World Federation of Hemophilia. 1998 Jul:4(4):506-10 [PubMed PMID: 9873783]

Maffulli N,Binfield PM,King JB,Good CJ, Acute haemarthrosis of the knee in athletes. A prospective study of 106 cases. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 1993 Nov [PubMed PMID: 8245089]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLan HH,Eustace SJ,Dorfman D, Hemophilic arthropathy. Radiologic clinics of North America. 1996 Mar [PubMed PMID: 8633126]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSoucie JM, Cianfrini C, Janco RL, Kulkarni R, Hambleton J, Evatt B, Forsyth A, Geraghty S, Hoots K, Abshire T, Curtis R, Forsberg A, Huszti H, Wagner M, White GC 2nd. Joint range-of-motion limitations among young males with hemophilia: prevalence and risk factors. Blood. 2004 Apr 1:103(7):2467-73 [PubMed PMID: 14615381]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAponte EM,Novik JI, Identification of lipohemarthrosis with point-of-care emergency ultrasonography: case report and brief literature review. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2013 Feb [PubMed PMID: 22981316]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDougados M. Synovial fluid cell analysis. Bailliere's clinical rheumatology. 1996 Aug:10(3):519-34 [PubMed PMID: 8876957]

Ryu KN,Jaovisidha S,De Maeseneer M,Jacobson J,Sartoris DJ,Resnick D, Evolving stages of lipohemarthrosis of the knee. Sequential magnetic resonance imaging findings in cadavers with clinical correlation. Investigative radiology. 1997 Jan [PubMed PMID: 9007642]

Lugo-Olivieri CH, Scott WW Jr, Zerhouni EA. Fluid-fluid levels in injured knees: do they always represent lipohemarthrosis? Radiology. 1996 Feb:198(2):499-502 [PubMed PMID: 8596856]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAllum R. The management of acute traumatic haemarthrosis of the knee. British journal of hospital medicine. 1997 Aug 20-Sep 2:58(4):138-41 [PubMed PMID: 9373401]

Simpson ML,Valentino LA, Management of joint bleeding in hemophilia. Expert review of hematology. 2012 Aug [PubMed PMID: 22992238]

Kisker CT,Burke C, Double-blind studies on the use of steroids in the treatment of acute hemarthrosis in patients with hemophilia. The New England journal of medicine. 1970 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 4907066]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGomis M, Querol F, Gallach JE, González LM, Aznar JA. Exercise and sport in the treatment of haemophilic patients: a systematic review. Haemophilia : the official journal of the World Federation of Hemophilia. 2009 Jan:15(1):43-54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01867.x. Epub 2008 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 18721151]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceIorio A, Fabbriciani G, Marcucci M, Brozzetti M, Filipponi P. Bone mineral density in haemophilia patients. A meta-analysis. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2010 Mar:103(3):596-603. doi: 10.1160/TH09-09-0629. Epub 2010 Jan 13 [PubMed PMID: 20076854]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBlamey G, Forsyth A, Zourikian N, Short L, Jankovic N, De Kleijn P, Flannery T. Comprehensive elements of a physiotherapy exercise programme in haemophilia--a global perspective. Haemophilia : the official journal of the World Federation of Hemophilia. 2010 Jul:16 Suppl 5():136-45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2010.02312.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20590873]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencevan Velzen AS, Eckhardt CL, Streefkerk N, Peters M, Hart DP, Hamulyak K, Klamroth R, Meijer K, Nijziel M, Schinco P, Yee TT, van der Bom JG, Fijnvandraat K, INSIGHT study group. The incidence and treatment of bleeding episodes in non-severe haemophilia A patients with inhibitors. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2016 Mar:115(3):543-50. doi: 10.1160/TH15-03-0212. Epub 2015 Nov 19 [PubMed PMID: 26582077]

Rodriguez-Merchan EC, Peripheral nerve injuries in haemophilia. Blood transfusion = Trasfusione del sangue. 2014 Jan [PubMed PMID: 23245720]

Ingram GI, Mathews JA, Bennett AE. Controlled trial of joint aspiration in acute haemophilic haemarthrosis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 1972 Sep:31(5):423 [PubMed PMID: 5071639]

Bernal-Lagunas R, Aguilera-Soriano JL, Berges-Garcia A, Luna-Pizarro D, Perez-Hernandez E. Haemophilic arthropathy: the usefulness of intra-articular oxytetracycline (synoviorthesis) in the treatment of chronic synovitis in children. Haemophilia : the official journal of the World Federation of Hemophilia. 2011 Mar:17(2):296-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2010.02402.x. Epub 2010 Nov 11 [PubMed PMID: 21070486]

Thomas S, Gabriel MB, Assi PE, Barboza M, Perri ML, Land MG, Da Costa ES, Brazilian Hemophilia Centers. Radioactive synovectomy with Yttrium⁹⁰ citrate in haemophilic synovitis: Brazilian experience. Haemophilia : the official journal of the World Federation of Hemophilia. 2011 Jan:17(1):e211-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2010.02379.x. Epub 2010 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 20731723]

van Kasteren ME, Nováková IR, Boerbooms AM, Lemmens JA. Long term follow up of radiosynovectomy with yttrium-90 silicate in haemophilic haemarthrosis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 1993 Jul:52(7):548-50 [PubMed PMID: 8346985]

Rattray B, Nugent DJ, Young G. Celecoxib in the treatment of haemophilic synovitis, target joints, and pain in adults and children with haemophilia. Haemophilia : the official journal of the World Federation of Hemophilia. 2006 Sep:12(5):514-7 [PubMed PMID: 16919082]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTsoukas C, Eyster ME, Shingo S, Mukhopadhyay S, Giallella KM, Curtis SP, Reicin AS, Melian A. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of etoricoxib in the treatment of hemophilic arthropathy. Blood. 2006 Mar 1:107(5):1785-90 [PubMed PMID: 16291600]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSchild FJ, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, Verbout AJ, Van Rinsum AC, Roosendaal G. Total knee arthroplasty in hemophilic arthropathy: efficiency of clotting factor usage in multijoint procedures. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 2009 Oct:7(10):1741-3. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03569.x. Epub 2009 Aug 11 [PubMed PMID: 19682237]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStoffman J, Andersson NG, Branchford B, Batt K, D'Oiron R, Escuriola Ettingshausen C, Hart DP, Jiménez Yuste V, Kavakli K, Mancuso ME, Nogami K, Ramírez C, Wu R. Common themes and challenges in hemophilia care: a multinational perspective. Hematology (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2019 Dec:24(1):39-48. doi: 10.1080/10245332.2018.1505225. Epub 2018 Aug 3 [PubMed PMID: 30073913]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence