Introduction

Anemia is a decrease in hemoglobin levels from an individual's baseline; however, sex-specific and race-specific reference ranges to make a diagnosis are often used when baseline hemoglobin is not known. The World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for anemia in men is less than 13 g/dL, whereas it is less than 12 g/dL for women. There are revised criteria for anemia in men and women with complications of chemotherapy as well as age and race. Even "special populations" such as athletes, smokers, older adults, or those living at high altitudes have suggested different ranges.

The critical issue in evaluating any form of anemia is to recognize treatable causes early. This is crucial because hemoglobin, an iron-rich protein, is what helps red blood cells (RBC), carry oxygen from the lungs to the rest of the body. The biconcave shape of RBCs themselves allows for it to provide optimal respiratory exchange. If the body is unable to provide oxygen to the body, one may experience symptoms of weakness, lethargy, dizziness, headaches, shortness of breath, or arrhythmias.

Anemia is often subcategorized into microcytic, normocytic, and macrocytic based on mean corpuscular volume (MCV). As there are numerous types of anemia, this laboratory parameter allows clinicians to formulate a practical diagnostic approach.

Hemolytic anemia is classified as normocytic anemia with an MCV of 80 to 100 fL. It is a form of low hemoglobin due to the destruction of red blood cells, increased hemoglobin catabolism, decreased levels of hemoglobin, and an increase in efforts of bone marrow to regenerate products.

Hemolytic Anemias can be further subdivided into intrinsic and extrinsic causes.[1][2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

There are numerous causes of hemolytic anemia, which have several ways that can be broken down to include acute and chronic disease, immune vs. non-immune mediated, intravascular or extravascular, inherited or acquired, and intracorpuscular or extracorpuscular.

Intracorpuscular causes refer to abnormalities in the red blood cell itself. A red blood cell can be internally damaged when the solubility of hemoglobin is altered (hemoglobinopathy), the structure of the membrane or cytoskeleton is changed (membranopathy), or its metabolic abilities (enzymopathy) is decreased. Examples of hemoglobinopathies include sickle cell disease (SCD) and thalassemias. SCD is caused by a beta-globin gene mutation leading to polymerization of hemoglobin-S, sticking, and, therefore, hemolysis. Thalassemia is the most common cause of hereditary hemolytic anemia and is caused by partial or complete lack of synthesis of one of the major alpha or beta globin chains of hemoglobin A.[3]

Membranopathies include hereditary spherocytosis (HS) and hereditary elliptocytosis (HE). HS is often autosomal dominant; however, non-dominant and recessive traits have been seen. It has been seen in all racial groups. HS has been documented as a rare disease, however, due to limited knowledge as the onset and severity vary considerably, as well as, the lack of specific lab tests, make it a difficult disease to study. HE is a heterogeneous red cell membrane disordered where the autosomal dominant inheritance can lead to a spectrum of presentations from asymptomatic to life-threatening.[4][5]

Several RBC enzymopathies alter the shape of RBCs and cause nonspherocytic hemolytic anemias.[2] G6PD deficiency and pyruvate kinase deficiency (PKD) both fall into this category. PK is the rate-limiting enzyme in RBC energy production, whereas G6PD is involved in the processing of carbohydrates and plays a protective role from reactive oxygen species in RBCs.[6] G6PD deficiency is an X-linked inherited disorder, almost exclusively seen in males, that causes hemolysis often with certain medications or foods such as fava beans and aspirin.[3]

Alternatively, extracorpuscular causes refer to defects that were influenced by external factors, including mechanical, immune-mediated, or infectious. RBC transfusions can cause both acute and delayed hemolytic reactions. Mechanical trauma to RBCs is seen with microthrombi, fibrin, or valve shearing forces. Pathogens such as malaria and babesiosis are known to destroy RBCs as well as medications like dapsone, that can be used to treat these diseases, also have deleterious effects as it has oxidant potential.

Epidemiology

Two databases exist which provide a systematic exclusion of the population of people that are not “normal”: NHANES-III (the third U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) database and the Scripps-Kaiser database.

Through these databases, one can see there is no difference in hemoglobin values of men from 20 to 59 or women 20 to 49. This assists in studying patient populations whose values do fall out of the norm from these ranges.

African Americans are found to have a lower limit of normal hemoglobin concentration, lower serum transferrin saturation, higher serum ferritin levels, lower bilirubin levels, and lower leukocyte counts. This is thought to be due to the higher frequency of alpha-thalassemia and G6PD deficiency in the black population. G6PD deficiency is known to affect millions of people worldwide.[7][8][9]

Although it can be seen worldwide, HE is most predominantly seen in malaria-endemic regions of West Africa.[5] Several forms of anemia are seen in these regions, as it is often thought to be protective against malaria.

Overall hemolytic anemias cover a broad range of age groups, races, and both genders as several subcategories can be acquired or inherited.

Pathophysiology

Hemolytic anemia is the destruction of RBCs. Normally, red blood cells have a lifespan of 120 days. This process can be something chronic that has occurred over time or acute and life-threatening. It can be further subdivided as to where the hemolysis is taking place - intravascularly or extravascularly.

When a red blood cell is unable to change shape as it passes through the spleen, it will become sequestered and phagocytosis will occur. This is seen in hemoglobinopathies such as sickle cell disease.

Destruction can also occur with inherited protein deficits (membranopathies ie hereditary spherocytosis), fragmentation [microangiopathic hemolytic anemias ie. thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), HELLP], increased oxidative stress or decreased energy production (enzymopathies ie. G6PD Deficiency), antibodies binding with RBC’s resulting in phagocytosis (immune-mediated), drug-induced hemolysis, infections, or direct trauma (conga drums).[10]

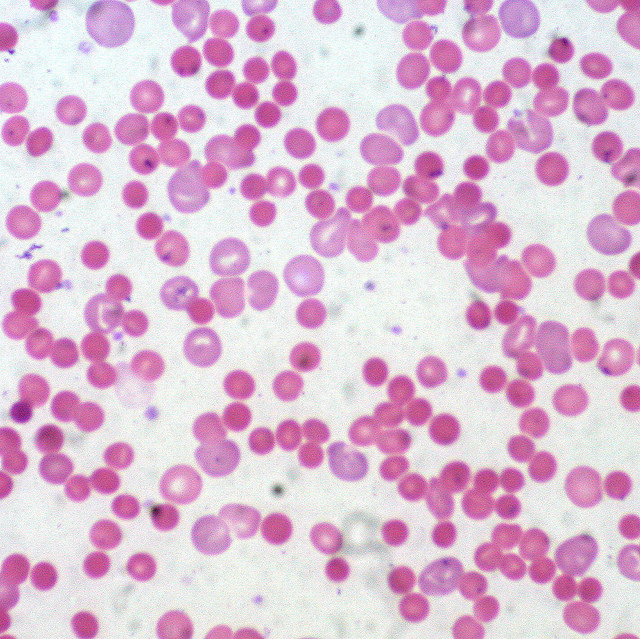

Histopathology

A peripheral blood smear should be studied when there is concern for hemolysis. One would look for abnormal red blood cells such as schistocytes, spherocytes, or bite cells.[10]

RBC shape is crucial in diagnosis. A distinctive blood smear may even be sufficient for the diagnosis of a type of hemolytic anemia. This can be seen in cases such as hereditary elliptocytosis or Southeast Asian ovalocytosis.

However, other hemolytic anemias may have similar features such as red cell fragmentation, as seen in microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA) and mechanical hemolytic anemia from leaking prosthetic valves.

Oxidant damage produces specific types of red blood cells, therefore, aiding in the diagnosis from a blood smear. Keratocytes or "bite" cells, "blister" cells, and irregularly contracted cells must be differentiated from spherocytes as it will alter one's diagnosis.[9]

History and Physical

A patient with anemia may present with shortness of breath, weakness, fatigue, arrhythmias such as tachycardia, or can present asymptomatic. Those with anemia caused by cell destruction or hemolysis may also present with jaundice or hematuria. If symptoms have been going on for longer periods, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, cholestasis may even be seen.

Specific physical exam findings may be able to lead a clinician to a suggested diagnosis. If a patient presents with diarrhea and hemolytic anemia, one may consider hemolytic uremic syndrome. Hematuria, in conjunction with labs supportive of hemolytic anemia, could be a sign of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH).[10]

A thorough history must be taken, and a physical exam performed as these clues can connect the information to form a diagnosis.

Evaluation

Although a patient may present with physical characteristics that may lead a clinician down the path to diagnosing hemolytic anemia, laboratory markers are key. Results that will help confirm hemolysis are an elevated reticulocyte count, increased lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), elevated unconjugated bilirubin, and decreased Haptoglobin.

LDH is found intracellularly, therefore when RBCs rupture, this value increases. Haptoglobin binds free hemoglobin. Therefore as this protein is fully bound with what little hemoglobin is left, it results in decreased levels of overall Haptoglobin. Unconjugated bilirubin is elevated as the body is unable to eliminate it as quickly as it is produced with the destruction of RBCs.

Warm and cold agglutinins can further differentiate whether the cause is immune-mediated. A direct antiglobulin test (DAT) must be performed.[10]

Hemoglobin concentration, or degree of anemia, can be used as an indicator of the extent of hemolysis that occurs in sickle cell disease (SCD). The inverse correlation of low hemoglobin concentration to a high degree of hemolysis has been supported by evidence of clinical measures such as LDH, reticulocyte count, and indirect bilirubin.[11]

Treatment / Management

Depending on the severity of illness, immediate interventions, including blood transfusions, plasmapheresis, or diuresis, may need to be performed depending on the cause of hemolytic anemia.

Blood transfusions are always the mainstay of treatment when there is severe anemia, especially when there is active bleeding. Once hemolysis is the known cause of anemia, or if no emergent intervention is required, more specific treatment modalities may be followed. However, the treatment will always vary depending on the cause.

If the cause is initially unclear, performing a direct antiglobulin (Coombs) test can be used to differentiate between an immune or non-immune cause of hemolysis.

For patients with SCD, blood transfusions, hydroxyurea, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, and bone marrow transplants are possible options with demonstrated effect.[11](A1)

A blood smear should be performed, especially when G6PD deficiency is being ruled out as it can be performed more rapidly than an assay. Additionally, there is the possibility of a false negative assay, while the smear is still suggestive of G6PD deficiency.[9] Once the diagnosis is known, patients must avoid medications and foods that will worsen the oxidative process.

As the most feared complication of PNH is a thromboembolic event, some recommend starting prophylactic anticoagulation; however, further studies must be performed to create a proper treatment regimen as well as define who would benefit most from this anticoagulation.[3](B3)

Splenectomy, steroids, monoclonal antibodies, or immunosuppressants have been used as late treatment options for certain diseases such as autoimmune hemolytic anemias, HS, and SCD.[10][12](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

One of the main laboratory values that aids in the diagnosis of hemolytic anemia is an elevated reticulocyte count, as the bone marrow is attempting to produce increased amounts of RBCs. This can be seen in other disease processes such as blood loss anemia; therefore, one must be cautious in taking a thorough history as well as evaluating other lab values that should also be altered, including LDH, haptoglobin, and indirect bilirubin.

Hemolysis can be seen in many rare conditions from paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria to blood transfusions or mechanical circulatory support; therefore, a wide differential must be ruled out.[3] However, to assist one in making this distinction, there have been case reports that help separate intravascular hemolysis from diseases such as PNH, from those like heart valves with mechanical prosthesis as kidney injury is less seen in the latter unless there is underlying kidney disease.[13]

Prognosis

Overall the development of anemia increases the risk for mortality in many clinical diseases such as chronic kidney disease, heart failure, and malignancy. This is seen in the publication of landmark trials such as TRICC, TRISS, and TRACS as their goals were to see what was the lowest level of anemia that could be tolerated without increasing mortality.

The prognosis for hemolytic anemias again varies on the cause of the illness as well as how early it is diagnosed and managed appropriately.

Studies have shown that patients with SCD had poorer outcomes. Specifically, hemoglobins of less than 8 g/dL are more likely to have complications during admissions, such as strokes, and increased mortality.[11]

Patients who are diagnosed with autoimmune hemolytic anemia with marked anemia at onset are at increased risk of multiple relapses as well as more often seen to be refractory to multiple lines of treatment.[12]

As the main treatment for G6PD deficiency is the avoidance of oxidative stressors, the disease is rarely fatal. However, these patients are more predisposed to sepsis and complications from infections.[14]

Complications

Hemolytic anemia can affect multiple organ systems throughout the body. As RBCs are destroyed, their products cause a chain of reactions that lead to further complications.

In SCD, the chronic hemolysis that occurs decreases the amount of oxygen that can be delivered, further leading to tissue hypoxia. As tissues are deprived of blood and, therefore, oxygen, patients can experience fatigue and muscle pain. The worse the degree of anemia has shown worse clinical outcomes in patients with SCD.[11]

The risk of ischemia and thrombotic complications can be seen in any case of hemolysis as there are more complications being studied from the toxic effects of circulating free hemoglobin and iron.

Thromboembolism is the most common cause of death in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH). 15% to 44% of these patients will have at least one thromboembolic event during their disease course. Thalassemia and SCD both are found to have a hypercoagulable state caused by an abnormal phospholipid membrane asymmetry, which has been linked to increased hemolysis and thrombosis.[3]

Excess hemoglobin and iron from hemolysis also are seen to cause complications in the kidneys. Iron and hemosiderin deposition in the kidneys with intravascular hemolysis, such as in PNH, have shown decreases in kidney function.[13]

Both liver disease and neurological deficits can be seen in Wilson disease if it is not diagnosed and treated early. Hemolysis is one of the most important presenting symptoms in a child or young adult with Wilson disease.[15]

Many people with HS are not diagnosed until adulthood when they begin to present with complications. They can often be seen to have recurrent cholelithiasis, and in the most severe cases, which are often found to be recessive, will need regular blood transfusions.[5]

Consultations

While initial labs and workup for hemolytic anemia can be performed by a primary care provider, hematology should be consulted for newly diagnosed hemolysis. These patients have the ability to decompensate acutely and may require urgent interventions with the coordination of multiple teams for medications and infusions.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Hemolytic anemia has many subsets within its disease process. Patients often require a full team of medical professionals and specialists to treat their class of hemolytic anemia. While many have medications that can be taken or simple deterrence from triggers to avoid any complications, others can have serious consequences. Patients must be educated on the symptoms of worsening clinical status or the beginnings of infections that can lead to further morbidity due to their disease process.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

While the initial workup for hemolytic anemia can begin with a general practitioner in a non-urgent setting or even an emergency physician, a thorough diagnosis and continued treatment can be difficult and challenging. An interprofessional team that incorporates a hematologist is often crucial. Once specific lab markers and blood smears are obtained and reviewed, the cause of hemolytic anemia can be determined. When a patient presents to the emergency department compromised and decompensated, blood transfusions may need to be given when the cause is unknown. However, if a thorough workup is able to be performed, it is crucial to systematically diagnose the cause of hemolytic anemia as the treatment for one category may be harmful in another. Furthermore, as the treatment is diverse among hemolytic anemias, the morbidity and mortality outcomes vary just as much.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Tefferi A. Anemia in adults: a contemporary approach to diagnosis. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2003 Oct:78(10):1274-80 [PubMed PMID: 14531486]

van Wijk R, van Solinge WW. The energy-less red blood cell is lost: erythrocyte enzyme abnormalities of glycolysis. Blood. 2005 Dec 15:106(13):4034-42 [PubMed PMID: 16051738]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceL'Acqua C, Hod E. New perspectives on the thrombotic complications of haemolysis. British journal of haematology. 2015 Jan:168(2):175-85. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13183. Epub 2014 Oct 13 [PubMed PMID: 25307023]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceXue J, He Q, Xie X, Su A, Cao S. Clinical utility of targeted gene enrichment and sequencing technique in the diagnosis of adult hereditary spherocytosis. Annals of translational medicine. 2019 Oct:7(20):527. doi: 10.21037/atm.2019.09.163. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31807509]

Narla J, Mohandas N. Red cell membrane disorders. International journal of laboratory hematology. 2017 May:39 Suppl 1():47-52. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12657. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28447420]

. . :(): [PubMed PMID: 32165483]

Beutler E, Waalen J. The definition of anemia: what is the lower limit of normal of the blood hemoglobin concentration? Blood. 2006 Mar 1:107(5):1747-50 [PubMed PMID: 16189263]

Beutler E, West C. Hematologic differences between African-Americans and whites: the roles of iron deficiency and alpha-thalassemia on hemoglobin levels and mean corpuscular volume. Blood. 2005 Jul 15:106(2):740-5 [PubMed PMID: 15790781]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBain BJ. Diagnosis from the blood smear. The New England journal of medicine. 2005 Aug 4:353(5):498-507 [PubMed PMID: 16079373]

Phillips J, Henderson AC. Hemolytic Anemia: Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis. American family physician. 2018 Sep 15:98(6):354-361 [PubMed PMID: 30215915]

Ataga KI, Gordeuk VR, Agodoa I, Colby JA, Gittings K, Allen IE. Low hemoglobin increases risk for cerebrovascular disease, kidney disease, pulmonary vasculopathy, and mortality in sickle cell disease: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2020:15(4):e0229959. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229959. Epub 2020 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 32243480]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJäger U, Barcellini W, Broome CM, Gertz MA, Hill A, Hill QA, Jilma B, Kuter DJ, Michel M, Montillo M, Röth A, Zeerleder SS, Berentsen S. Diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune hemolytic anemia in adults: Recommendations from the First International Consensus Meeting. Blood reviews. 2020 May:41():100648. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2019.100648. Epub 2019 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 31839434]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceQian Q, Nath KA, Wu Y, Daoud TM, Sethi S. Hemolysis and acute kidney failure. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2010 Oct:56(4):780-4. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.03.025. Epub 2010 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 20605299]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFrank JE. Diagnosis and management of G6PD deficiency. American family physician. 2005 Oct 1:72(7):1277-82 [PubMed PMID: 16225031]

Walshe JM. The acute haemolytic syndrome in Wilson's disease--a review of 22 patients. QJM : monthly journal of the Association of Physicians. 2013 Nov:106(11):1003-8. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hct137. Epub 2013 Jul 9 [PubMed PMID: 23842488]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence