Introduction

Hemothorax is a frequent consequence of traumatic thoracic injuries. It is a collection of blood in the pleural space, a potential space between the visceral and parietal pleura. The most common mechanism of trauma is a blunt or penetrating injury to intrathoracic or extrathoracic structures that result in bleeding into the thorax. Bleeding may arise from the chest wall, intercostal or internal mammary arteries, great vessels, mediastinum, myocardium, lung parenchyma, diaphragm, or abdomen.

CT scan is the preferred method of evaluation for intrathoracic injuries; however, it may not be feasible in the unstable trauma patient. Furthermore, smaller centers may not have CT scan readily available. Chest radiography has been used traditionally as a screening tool to evaluate for immediate life-threatening injuries. Recent literature suggests point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) can be useful as an adjunct to traditional imaging modalities. POCUS is rapid, reliable, repeatable, and most importantly, portable. It is usable at the bedside for triage and identification of life-threatening injuries. Pulmonary windows have been included in the Extended-Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (eFAST) protocol since the mid-2000s. In addition to the traditional right and left upper quadrant views of the FAST, the operator can slide the probe cephalad to evaluate quickly for the presence of fluid above the diaphragm. Multiple studies have shown that chest ultrasonography is a valuable tool in the diagnostic approach of patients with blunt chest trauma.[1][2][3][4][5] Lung ultrasound (US) in the evaluation for hemothorax has demonstrated accuracy, with higher sensitivity than chest radiography.[2][5][6][7]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Hemothorax is a frequent manifestation of traumatic injury (blunt or penetrating) to thoracic structures. Most cases of hemothorax arise from blunt mechanism with an overall mortality of 9.4%.[8] Non-traumatic causes are less common. Examples include iatrogenic, lung sequestration, vascular, neoplasia, coagulopathies, and infectious processes.[9]

Epidemiology

Traumatic injuries are a major health concern in the United States, contributing to 140000 deaths annually.[10] Thoracic injuries occur in approximately 60% of multi-trauma cases and are responsible for 20 to 25% of trauma mortalities.[6] Furthermore, trauma is the leading cause of mortality in the fourth decade of life.[7] In the United States, motor vehicle accidents account for 70 to 80% of blunt chest trauma.[11] Injury to thoracic structures might arise from direct impact or rapid deceleration forces. Recent studies show thoracic skeletal fractures, lung contusion, and diaphragmatic injuries are common findings in blunt chest trauma.[12] Thirty to fifty percent of patients with severe blunt chest injury had a concomitant pulmonary contusion, pneumothorax, and hemothorax.[11][13] Pneumothorax, hemothorax, or hemopneumothorax were found in 72.3% of the cases of traumatic rib fractures, in a series by Sirmali et al.[12]

Pathophysiology

Bleeding into the hemithorax may arise from diaphragmatic, mediastinal, pulmonary, pleural, chest wall and abdominal injuries. Each hemithorax can hold 40% of a patient's circulating blood volume. Studies have shown that injury to intercostal vessels (e.g., internal mammary arteries and pulmonary vessels) lead to significant bleeding requiring invasive management.[13] Early physiologic response of a hemothorax has hemodynamic and respiratory components. The severity of the pathophysiologic response depends on the location of the injury, the patient's functional reserve, the volume of blood, and the rate of accumulation in the hemithorax.[14][15][16] In the early response, acute hypovolemia leads to a decrease in preload, left ventricular dysfunction and a decrease in cardiac output. Blood in the pleural space affects the functional vital capacity of the lung by creating alveolar hypoventilation, V/Q mismatch, and anatomic shunting. A large hemothorax can lead to an increase in hydrostatic pressure which exerts pressure in the vena cava and pulmonary parenchyma causing impairment in preload and increase pulmonary vascular resistance. These mechanisms result in tension hemothorax physiology and cause hemodynamic instability, cardiovascular collapse, and death.

History and Physical

Thorough and accurate gathering of history from the patient, witnesses, or prehospital providers helps determine those patients that are at low vs. high risk of intrathoracic injury. Important history components include chest pain, dyspnea, mechanism of injury (fall, direction, and speed), drug/alcohol use, comorbidities, surgical history, and anticoagulation/antiplatelet therapies. The mechanisms of action that were predictive of significant thoracic injury are motor vehicle accident greater than 35 mph, fall from more than 15 feet, pedestrian ejection of more than 10 feet, and trauma with depressed level of consciousness.[14]

Clinical findings of hemothorax are broad and may overlap with pneumothorax; these include respiratory distress, tachypnea, decreased or absent breath sounds, dullness to percussion, chest wall asymmetry, tracheal deviation, hypoxia, narrow pulse pressure, and hypotension. Inspect the chest wall for signs of contusion, abrasions, "seat belt sign," penetrating injury, paradoxical movement ("flail chest”), ecchymosis, deformities, crepitus, and point tenderness. Distended neck veins are concerning for pneumothorax or pericardial tamponade but might be absent in the setting of hypovolemia. Increased respiratory rate, effort, and use of accessory muscles may be signs of impending respiratory failure.

The following physical findings should prompt the clinician to consider these conditions:

- Distended neck veins → pericardial tamponade, tension pneumothorax, cardiogenic failure, air embolism

- "Seat belt sign" → deceleration or vascular injury; chest wall contusion/abrasion

- Paradoxical chest wall movement → flail chest

- Facial/neck swelling or cyanosis → superior mediastinum injury with occlusion or compression of superior vena cava (SVC)

- Subcutaneous emphysema → torn bronchus or lung parenchyma laceration

- Scaphoid abdomen → diaphragmatic injury with herniation of abdominal content into the chest

- Excessive abdominal movement with breathing → chest wall injury

Evaluation

Rapid evaluation, recognition, and intervention of potential chest injuries are essential. The American College of Surgeons established the American Traumatic Life Support (ATLS) protocol which implements a standardized and methodical approach of evaluation for every trauma patient.[17] In the setting of traumatic chest injuries, cardiopulmonary assessment should take priority since they have the highest mortality index if missed.[18] Injuries to other thoracic structures must merit consideration; ribs, clavicle, trachea, bronchi, esophagus, and vessels.

Diagnostics: The dawn of POCUS

Imaging plays a very critical role in the management of traumatic injuries. First described by Rozycki et al., the Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (FAST) exam evaluates the pericardium, perihepatic, perisplenic, and pelvis for pathologic fluid or air collection.[19]

It has shown to provide rapid and accurate evaluation of the traumatic patient with growing evidence to supporting its use to diagnose hemothorax, pneumothorax and lung contusion.[1][20] Lung ultrasound has inclusion in multiple undifferentiated dyspnea protocols: FALLS, BLUE.[21][22]

Point-of-care ultrasound in trauma has significantly impacted the evaluation and disposition of trauma patients.[23] It is portable, reproducible, non-invasive, reproducible, and employs no radiation or contrast agents.[7]

In addition to the four conventional views, the eFAST includes oblique views of both hemidiaphragm to evaluate for dependent fluid (hemothorax) and anterior views to evaluate for pneumothorax. In B mode, the transducer (5-1 MHz curvilinear or 5-1 MHz phased array) is placed mid-axillary in the fifth or sixth intercostal space, with the marker directed toward the patient's head. In a well-aerated, healthy lung, air prevents direct visualization of structures deep to the interface of the diaphragm and the visceral pleura of the lung. A hemothorax will appear as an anechoic (black) or echo-poor space in between the diaphragm and the parietal pleura within the costophrenic recess.[24] Fluid may also contain heterogeneous echoes from clotted blood or portion of lacerated lung tissue. The presence of pleural fluid allows visualization of the thoracic spine beyond the costophrenic angle, known as the "spine sign." This phenomenon is due to the loss of mirroring artifact of the diaphragm[5]

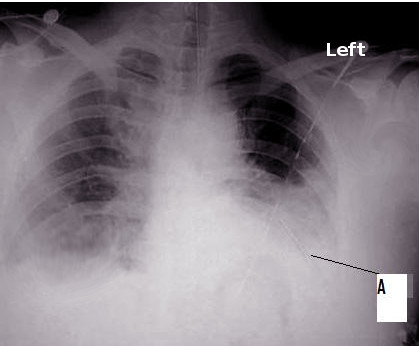

Chest x-ray continues to be the initial diagnostic tool in the screening of traumatic thoracic injuries. When compared to ultrasonography, studies show that ultrasound is a superior diagnostic tool in detection of traumatic thoracic injuries (e.g., pneumothorax and hemothorax).[5][6][7][20] A systemic review reported that ultrasound has a higher sensitivity (67%) compared to chest x-ray (54%).[6] Sensitivity was even higher, at 70%, when an emergency physician performed the eFAST. In a prospective study, sensitivity and specificity of thoracic ultrasonography in the detection of hemothorax were 92% and specificity of 100% respectively.[1] Furthermore, ultrasound can detect as little as 20 ml of pleural fluid compared to 175 ml with radiography,[6] and is 100% sensitive for detecting effusions greater than 100 mL.[24]

Another feature of the ultrasound is its ability to quantify effusion volume. Four different sonographic formulas have been elaborated and studied for volume prediction. Two of the four formulas are while the patient is supine. The transducer is placement is perpendicular to the chest wall, and measurements taken at maximum inspiration, with the patients holding their breath. "X" is the maximum perpendicular (interpleural) distance in mm between the posterior surface of the lung (visceral pleura) and the posterior chest wall (parietal pleura) get measured.[25]

The formulas are the following

- Estimated Volume (EV) = 47.6X - 837 (Eibenberger)

- EV = 20X (Balik)

The other two formulas are performed with the patient sitting up (erect) which are beyond this discussion.

The recommended work-up of hemothorax includes CBC (baseline hemoglobin), CMP (creatinine), troponin, coagulation profile, and type and screen.[14] Multiple studies report serum lactate as a predictor of mortality in the setting of trauma. Data is mostly from retrospective studies, and none were performed in the setting of blunt chest trauma. Serum lactate level above 4mg/dL correlates with higher mortality. Serial troponins should be obtained in adjunct with EKG for evaluation of cardiac contusion.

Treatment / Management

Perform initial resuscitation and management of a trauma patient according to the ATLS protocol. Every patient should have two large bore IVs access, be placed on a cardiac and oxygen monitor, and have a 12-lead EKG. Immediate life-threatening injuries require prompt intervention, such as decompression needle thoracostomy, and/or emergent tube thoracostomy for large pneumothoraces, and initial management of hemothorax.[26]

Minimal collection of blood (defined as less than 300 ml) in the pleural cavity generally requires no treatment; blood usually reabsorbs throughout the course of several weeks. If the patient is stable and has minimal respiratory distress, operative intervention is not typically required. This group of patients can be treated by analgesia as needed and observed with repeated imaging at 4 to 6 hours and 24 hours.

When possible, consultation with cardiothoracic or trauma surgery should be performed for placement of tube thoracostomy. Traditionally, 36 - 40 French chest tubes have been used for evacuation of hemothoraces, but this practice has come under scrutiny. Recent studies show that most surgeons use 32 - 36 French tubes. Prospective studies demonstrate no difference in outcomes when 28 to 32 French tubes were used in level I trauma centers for hemothorax evacuation.[17]

With an aseptic approach, the tube is placed posteriorly towards gravity-dependent fluid, in the fourth or fifth intercostal space between the anterior and mid-axillary line. The thoracostomy tube is then connected to a water seal and suction to facilitate rapid drainage and prevent air leakage. Furthermore, tube insertion provides for blood quantification to determine if surgical intervention is needed.

According to the literature, indications for surgical intervention (urgent anterior thoracotomy) include:

- 1500 ml of blood drainage in 24 hours through the chest tube

- 300-500 ml/hour for 2 to 4 consecutive hours after chest tube insertion

- Great vessel or chest wall injury

- Pericardial tamponade

Thoracotomy allows for rapid assessment of intrathoracic injuries and hemostasis.

Drainage of hemothorax in case of coagulopathy should be performed carefully with consideration of the underlying disease. Correction of coagulation function before surgical intervention should be performed if permitted by clinical patient status.

Improper hemothorax evacuation may lead to complications like empyema and fibrothorax. Multiple studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of video-assisted thoracoscopy for management of retained hemothorax. It has had a positive impact on the length of stay in the hospital and survival of patients. VATS provides clear visualization of the pleural cavity, correct chest tube placement for accurate bleeding control, removal of the retained clot, evacuation and decortication of posttraumatic empyemas. Furthermore, it provides an evaluation of suspected diaphragmatic injuries, treatment of persistent air leaks, and evaluation of mediastinal injuries.[27]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of blunt chest trauma can be divided into three categories[14]:

Visceral injuries

- Ruptured diaphragm

- Pulmonary contusion

- Pneumothorax

- Hemothorax

- Tracheobronchial injuries

- Esophageal injury

- Pneumomediastinum

Skeletal Injuries

- Flail chest

- Rib fracture

- Sternoclavicular fractures or dislocations

- Scapular fracture

- Clavicular fracture or dislocation

- Vertebral or spinal injury

Cardiovascular injuries

- Aortic rupture

- Caval injury

- Pericardial effusion/tamponade

- Subclavian artery injury

- Intercostal artery injury

- Commotio cordis

- Cardiac laceration

Prognosis

Morbidity and mortality of traumatic hemothorax correlate with the severity of the injury and those at risk of late complications, namely empyema and fibrothorax/trapped lung. Patients with retained hemothorax are at risk of developing empyema resulting in a prolonged ICU/hospital stay.[27]

Complications

Thoracic ultrasound complications

- Minimal

- Point tenderness at the site of probe placement

Massive hemothorax may lead to

- Hemodynamic instability

- Shock

- Hypoxia

- Death

Improper chest tube placement may lead to

- Solid organ injury

Inadequate placement of chest tube may lead to insufficient hemothorax drainage which promotes empyema formation. Studies show a 26.8% incidence of empyema in patients with post-traumatic retained hemothorax. Fibrothorax results from fibrin deposition within the pleural space. Improper hemothorax drainage causes an inflammatory coating within the pleural space which impedes proper lung expansion. This phenomenon is known as lung entrapment.[28]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Studies show that lack of restraints and driver impairment are major factors contributing to severe injury in motor vehicle accidents.[29][30] Healthcare providers should encourage the adoption of safety measures such as wearing safety belts, avoidance of impaired driving, and alternative transportation strategies.[31][32][33]

Pearls and Other Issues

Point of care ultrasound has been accepted globally as a bedside examination in the emergency department. It also has been introduced to formal residency training. It allows a rapid and reproducible assessment of traumatic injuries without the risk of harmful radiation. Various studies have aimed to evaluate the diagnostic value of thoracic ultrasound in the setting of traumatic hemothorax. A systematic review and meta-analysis reported that the sensitivity of ultrasound was influenced by the operator and the frequency of the transducer.[6] A prospective cross-sectional study demonstrated that ultrasound is a superior modality than radiography, but when compared to CT scan it showed a lower sensitivity.[7]

A systematic review to determine the overall accuracy of ultrasound in traumatic thoracic injury has several limitations. Heterogeneous characteristics of ultrasound findings, with different machines, probes, and expertise levels affect the overall methodological quality of these studies.[5]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Point of care ultrasound in the evaluation of traumatic thoracic injury is a valuable adjunct tool. Its application in the setting of trauma has been studied and analyzed in multiple systematic reviews. Future randomized trials should be performed to assess relevant outcomes such as mortality, length of hospital stay and costs.[5][34] Nurses should monitor the chest tube output every hour during the initial admission; if the output is significant and continuous, the thoracic surgeon should be notified. While most cases resolve with a chest tube, if the hemothorax is not evacuated, it can lead to an empyema, which often requires surgery. The outcomes for most patients with isolated hemothorax are good.[35] (level V)

Media

(Click Video to Play)

(Click Video to Play)

References

Brooks A, Davies B, Smethhurst M, Connolly J. Emergency ultrasound in the acute assessment of haemothorax. Emergency medicine journal : EMJ. 2004 Jan:21(1):44-6 [PubMed PMID: 14734374]

Stengel D, Leisterer J, Ferrada P, Ekkernkamp A, Mutze S, Hoenning A. Point-of-care ultrasonography for diagnosing thoracoabdominal injuries in patients with blunt trauma. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2018 Dec 12:12(12):CD012669. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012669.pub2. Epub 2018 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 30548249]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAbboud PA, Kendall J. Emergency department ultrasound for hemothorax after blunt traumatic injury. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2003 Aug:25(2):181-4 [PubMed PMID: 12902006]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMcEwan K, Thompson P. Ultrasound to detect haemothorax after chest injury. Emergency medicine journal : EMJ. 2007 Aug:24(8):581-2 [PubMed PMID: 17652688]

Staub LJ, Biscaro RRM, Kaszubowski E, Maurici R. Chest ultrasonography for the emergency diagnosis of traumatic pneumothorax and haemothorax: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury. 2018 Mar:49(3):457-466. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2018.01.033. Epub 2018 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 29433802]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRahimi-Movaghar V, Yousefifard M, Ghelichkhani P, Baikpour M, Tafakhori A, Asady H, Faridaalaee G, Hosseini M, Safari S. Application of Ultrasonography and Radiography in Detection of Hemothorax; a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Emergency (Tehran, Iran). 2016 Summer:4(3):116-26 [PubMed PMID: 27299139]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVafaei A, Hatamabadi HR, Heidary K, Alimohammadi H, Tarbiyat M. Diagnostic Accuracy of Ultrasonography and Radiography in Initial Evaluation of Chest Trauma Patients. Emergency (Tehran, Iran). 2016 Winter:4(1):29-33 [PubMed PMID: 26862547]

Broderick SR. Hemothorax: Etiology, diagnosis, and management. Thoracic surgery clinics. 2013 Feb:23(1):89-96, vi-vii. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2012.10.003. Epub 2012 Nov 3 [PubMed PMID: 23206720]

Boersma WG, Stigt JA, Smit HJ. Treatment of haemothorax. Respiratory medicine. 2010 Nov:104(11):1583-7. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.08.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20817498]

Goodman M, Lewis J, Guitron J, Reed M, Pritts T, Starnes S. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for acute thoracic trauma. Journal of emergencies, trauma, and shock. 2013 Apr:6(2):106-9. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.110757. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23723618]

Özdil A, Kavurmacı Ö, Akçam Tİ, Ergönül AG, Uz İ, Şahutoğlu C, Yüzkan S, Çakan A, Çağırıcı U. A pathology not be overlooked in blunt chest trauma: Analysis of 181 patients with bilateral pneumothorax. Ulusal travma ve acil cerrahi dergisi = Turkish journal of trauma & emergency surgery : TJTES. 2018 Nov:24(6):521-527. doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2018.76435. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30516250]

Sirmali M, Türüt H, Topçu S, Gülhan E, Yazici U, Kaya S, Taştepe I. A comprehensive analysis of traumatic rib fractures: morbidity, mortality and management. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2003 Jul:24(1):133-8 [PubMed PMID: 12853057]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOta K, Fumimoto S, Iida R, Kataoka T, Ota K, Taniguchi K, Hanaoka N, Takasu A. Massive hemothorax due to two bleeding sources with minor injury mechanism: a case report. Journal of medical case reports. 2018 Oct 7:12(1):291. doi: 10.1186/s13256-018-1813-x. Epub 2018 Oct 7 [PubMed PMID: 30292243]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMorley EJ, Johnson S, Leibner E, Shahid J. Emergency department evaluation and management of blunt chest and lung trauma (Trauma CME). Emergency medicine practice. 2016 Jun:18(6):1-20 [PubMed PMID: 27177417]

Chou YP, Lin HL, Wu TC. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for retained hemothorax in blunt chest trauma. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine. 2015 Jul:21(4):393-8. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000173. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25978625]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceScott MF, Khodaverdian RA, Shaheen JL, Ney AL, Nygaard RM. Predictors of retained hemothorax after trauma and impact on patient outcomes. European journal of trauma and emergency surgery : official publication of the European Trauma Society. 2017 Apr:43(2):179-184. doi: 10.1007/s00068-015-0604-y. Epub 2015 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 26619854]

Edgecombe L, Sigmon DF, Galuska MA, Angus LD. Thoracic Trauma. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30521264]

Jain A, Sekusky AL, Burns B. Penetrating Chest Trauma. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30571065]

Richards JR, McGahan JP. Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (FAST) in 2017: What Radiologists Can Learn. Radiology. 2017 Apr:283(1):30-48. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017160107. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28318439]

Hyacinthe AC, Broux C, Francony G, Genty C, Bouzat P, Jacquot C, Albaladejo P, Ferretti GR, Bosson JL, Payen JF. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography in the acute assessment of common thoracic lesions after trauma. Chest. 2012 May:141(5):1177-1183. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0208. Epub 2011 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 22016490]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLichtenstein D. Novel approaches to ultrasonography of the lung and pleural space: where are we now? Breathe (Sheffield, England). 2017 Jun:13(2):100-111. doi: 10.1183/20734735.004717. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28620429]

Lichtenstein DA. BLUE-protocol and FALLS-protocol: two applications of lung ultrasound in the critically ill. Chest. 2015 Jun:147(6):1659-1670. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1313. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26033127]

Zieleskiewicz L, Fresco R, Duclos G, Antonini F, Mathieu C, Medam S, Vigne C, Poirier M, Roche PH, Bouzat P, Kerbaul F, Scemama U, Bège T, Thomas PA, Flecher X, Hammad E, Leone M. Integrating extended focused assessment with sonography for trauma (eFAST) in the initial assessment of severe trauma: Impact on the management of 756 patients. Injury. 2018 Oct:49(10):1774-1780. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2018.07.002. Epub 2018 Jul 8 [PubMed PMID: 30017184]

Soni NJ, Franco R, Velez MI, Schnobrich D, Dancel R, Restrepo MI, Mayo PH. Ultrasound in the diagnosis and management of pleural effusions. Journal of hospital medicine. 2015 Dec:10(12):811-6. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2434. Epub 2015 Jul 28 [PubMed PMID: 26218493]

Ibitoye BO, Idowu BM, Ogunrombi AB, Afolabi BI. Ultrasonographic quantification of pleural effusion: comparison of four formulae. Ultrasonography (Seoul, Korea). 2018 Jul:37(3):254-260. doi: 10.14366/usg.17050. Epub 2017 Oct 18 [PubMed PMID: 29228764]

Dennis BM, Gondek SP, Guyer RA, Hamblin SE, Gunter OL, Guillamondegui OD. Use of an evidence-based algorithm for patients with traumatic hemothorax reduces need for additional interventions. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2017 Apr:82(4):728-732. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001370. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28099387]

Gleeson T, Blehar D. Point-of-Care Ultrasound in Trauma. Seminars in ultrasound, CT, and MR. 2018 Aug:39(4):374-383. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2018.03.007. Epub 2018 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 30070230]

Tian Y, Zheng W, Zha N, Wang Y, Huang S, Guo Z. Thoracoscopic decortication for the management of trapped lung caused by 14-year pneumothorax: A case report. Thoracic cancer. 2018 Aug:9(8):1074-1077. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12770. Epub 2018 May 26 [PubMed PMID: 29802756]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBunn T, Singleton M, Chen IC. Use of multiple data sources to identify specific drugs and other factors associated with drug and alcohol screening of fatally injured motor vehicle drivers. Accident; analysis and prevention. 2019 Jan:122():287-294. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2018.10.012. Epub 2018 Nov 2 [PubMed PMID: 30396030]

Zhu M, Li Y, Wang Y. Design and experiment verification of a novel analysis framework for recognition of driver injury patterns: From a multi-class classification perspective. Accident; analysis and prevention. 2018 Nov:120():152-164. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2018.08.011. Epub 2018 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 30138770]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMorgan E. Driving Dilemmas: A Guide to Driving Assessment in Primary Care. Clinics in geriatric medicine. 2018 Feb:34(1):107-115. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2017.09.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29129210]

Ecola L, Popper SW, Silberglitt R, Fraade-Blanar L. The Road to Zero: A Vision for Achieving Zero Roadway Deaths by 2050. Rand health quarterly. 2018 Oct:8(2):11 [PubMed PMID: 30323994]

Han GM, Newmyer A, Qu M. Seatbelt use to save money: Impact on hospital costs of occupants who are involved in motor vehicle crashes. International emergency nursing. 2017 Mar:31():2-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2016.04.004. Epub 2016 May 10 [PubMed PMID: 27177737]

Chung MH, Hsiao CY, Nian NS, Chen YC, Wang CY, Wen YS, Shih HC, Yen DH. The Benefit of Ultrasound in Deciding Between Tube Thoracostomy and Observative Management in Hemothorax Resulting from Blunt Chest Trauma. World journal of surgery. 2018 Jul:42(7):2054-2060. doi: 10.1007/s00268-017-4417-5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29305713]

Carver DA, Bressan AK, Schieman C, Grondin SC, Kirkpatrick AW, Lall R, McBeth PB, Dunham MB, Ball CG. Management of haemothoraces in blunt thoracic trauma: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ open. 2018 Mar 3:8(3):e020378. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020378. Epub 2018 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 29502092]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence