Introduction

Alcohol enjoys widespread popularity in Western societies, with a prevalent belief that moderate consumption may confer cardioprotective benefits. Nevertheless, the adverse effects of excessive alcohol intake on cardiovascular health are well-documented [1].

The term "holiday heart syndrome" (HHS) is used to describe the manifestation of cardiac arrhythmias following a period of binge drinking, often observed during weekends and holidays.[1] This association between cardiac arrhythmias and binge drinking was originally introduced by Ettinger et al., who observed 24 patients getting hospitalized with atrial fibrillation after engaging in a weekend binge of alcohol consumption.[2] Subsequent research has demonstrated that HHS can also occur in individuals who rarely or never consume alcohol but occasionally engage in binge drinking.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Forty years ago, Ettinger et al. described the association between binge alcohol use and atrial fibrillation. These events occurred in close proximity to weekends and holidays when alcohol consumption increased [2]. Subsequently, several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have investigated the association between alcohol consumption and atrial fibrillation.[4][5]

As the majority of studies included in these systematic reviews and meta-analyses are retrospective, relying on self-reported alcohol consumption data obtained via questionnaires, there exists a potential for confounding due to recall bias. To address this confounding factor, Marcus et al. did a prospective study that utilized wearable monitors to capture alcohol consumption events in real time and demonstrated a causal association between acute alcohol intake and the incidence of atrial fibrillation in individuals with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation.[6]

In their study, they included 100 participants. 56% of them experienced an episode of atrial fibrillation. When monitored over four hours, participants who consumed two or more drinks had an odds ratio (OR, 3.58 [95% CI, 1.63 to 7.89]) of experiencing an atrial fibrillation episode. Participants who consumed a single drink had an odds ratio of (OR, 2.02 [95% CI, 1.38 to 3.17]). Additionally, analysis of the transdermal alcohol sensor measurements of blood alcohol concentration during the 12 hours preceding the AF episode revealed a 38% greater odds of AF per 0.1% increase in peak blood alcohol concentration.[6]

Epidemiology

Alcohol consumption is pervasive in Western nations, with a reported 53% of Americans consuming alcohol on a regular basis and 44% of drinkers (equivalent to 61 million individuals) engaging in binge drinking, defined as consuming five or more standard drinks during a single occasion.[1] Approximately one-quarter of annual sales of distilled spirits are believed to take place during the holiday season between Thanksgiving and New Year's Day (https://alcohol.org/statistics-information/holiday-binge-drinking/).

Holiday heart syndrome continues to be a prevalent occurrence in emergency department settings, with alcohol serving as a precipitating factor for atrial fibrillation in 35% to 62% of cases, especially 12 to 36 hours after cessation of binge drinking.[7][8] There is an observed trend for increased binge alcohol use in younger adults, which may be associated with a greater incidence of atrial fibrillation in this demographic.[9]

Pathophysiology

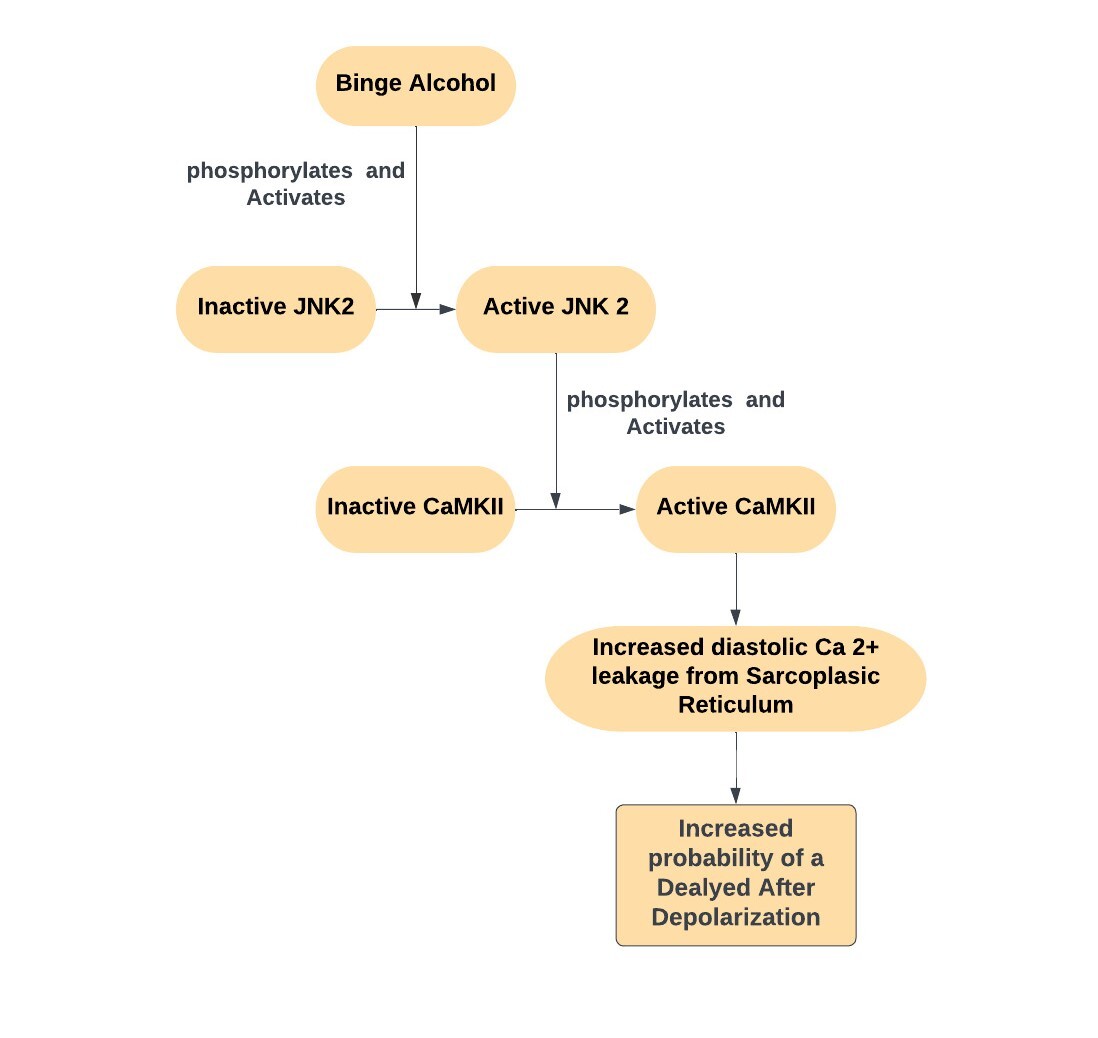

Previous literature has well established the relationship between heavy alcohol use and atrial fibrillation, although the underlying pathophysiology had relied mainly on loosely connected theories. In 2018, Yan et al. presented experimental evidence of the crucial involvement of JNK2/CaMKII pathway activation and its impact on diastolic calcium handling by cardiac myocytes in the development of paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation induced by binge alcohol consumption.[10]

Electrophysiological Effect of Alcohol

Yan et al. used animal models (mouse and rabbit atria) and human atrial tissue (from donor's hearts with and without histories of alcohol exposure) for their study. Animal models were exposed to well-controlled alcohol concentration and artificially paced to trigger atrial fibrillation. The ease of induction and duration of atrial fibrillation in alcohol-exposed animals and human atrial tissue exceeded that of sham and non–alcohol-exposed human tissue. Using optical mapping techniques and immunoblotting experiments, the authors proceeded to establish a connection between alcohol-induced increased cardiac myocyte JNK2 signaling and cardiac myocyte calcium dysregulation.[10]

Abnormal sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release during the repolarization phase of the action potential (diastolic phase of myocyte contraction cycle) increases the likelihood of a delayed afterdepolarization (DAD). Diastolic increase in calcium levels stimulates the sarcolemmal Na+/Ca+ exchanger. This generates a net inward positive depolarizing current (3 Na+ inward/1 Ca2+ outward). This current can prompt an action potential, which triggers atrial fibrillation in atrial myocytes.[11][12]

Autonomic Effect of Alcohol

"Hangover," which is often observed after binge alcohol, is believed to be a mild alcohol withdrawal state, which is characterized by sympathetic hyperactivity and a decrease in the atrial refractory period. One study demonstrated a 17% increase in resting heart rate in healthy nonalcoholics 12 hours post-binge.[13] In their double-blinded randomized control trial, Marcus et al. observed that alcohol exposure significantly decreased the refractory period of the pulmonary veins myocytes which are often the foci of ectopic atrial activity.[14]

Electrolyte Disturbances and Direct Toxic Effect of Alcohol

Alcohol is well known to have a diuretic effect. Heavy alcohol use may cause loss of intracellular and extracellular electrolytes, which are essential to maintain the membrane resting potential and therefore increase cardiac myocyte automaticity.[15] The accumulation of ethanol metabolites in myocardial tissue may cause oxidative stress and mitochondrial injury.[16]

History and Physical

History

Holiday heart syndrome typically refers to atrial fibrillation induced by binge alcohol consumption, frequently observed during long weekends, vacations, and holidays. The most common symptom that patients present with is palpitations.[1] Symptoms of palpitations can be transient or persistent. This depends on the presence or absence of sustained arrhythmia, as well as the ventricular response to atrial fibrillation. Patients with rapid ventricular responses may present with symptoms such as fatigue, generalized weakness, angina, shortness of breath, or near syncope.

Long-term alcohol use is often associated with multiple medical problems like chronic liver disease and alcohol-related cardiomyopathy. If co-existing, these conditions can have important prognostic implications.

Physical Examination

On presentation, patients may have signs of alcohol intoxication. They may have impaired mental status. Depending on their clinical manifestation, they may have elevated heart rates and low blood pressure. Pulses are thready and irregular. Cardiac auscultation may show irregularly irregular heart sounds. Chronic alcohol misusers with dilated cardiomyopathy may show clinical signs of congestive heart failure like elevated jugular venous pressure, extra heart sound (S3), crackles on lung auscultation, and lower extremity edema. Patients may have hepatomegaly on abdominal examination.[17]

Evaluation

Laboratory Tests

It is recommended to evaluate serum electrolyte levels, particularly potassium and magnesium. Hypomagnesemia and hypokalemia are frequently observed in individuals with alcoholism, particularly during initial hospital assessment.[18] Troponin levels and brain natriuretic peptides should be checked to rule out evidence of cardiac ischemia or cardiomyopathy, respectively. A complete blood count should be obtained as alcoholics are usually anemic and thrombocytopenic.[19]

Patients with atrial fibrillation may require systemic anticoagulation for stroke prophylaxis. The decision about indication and type of anticoagulation may depend on the patient's hemoglobin level and platelet count. A complete metabolic panel, including renal function and liver function, should be obtained as well. Many drugs used for managing atrial fibrillation need dose adjustment according to renal and hepatic clearance.

12 Lead Electrocardiogram and Telemetry Monitoring

Electrocardiogram is essential to rule out important differentials like acute coronary syndrome and pulmonary embolism. It is needed to identify the mechanism of tachycardia and the type of cardiac arrhythmia. These patients should be placed on a cardiac telemetry monitor to monitor heart rate trends and identify any initiation or termination events of arrhythmia.[17]

Chest X-ray

Chest X-ray is important in patients who have symptoms of shortness of breath and clinical signs of congestive heart failure. Chronic alcoholic patients presenting with rapid atrial fibrillation may have pulmonary vascular congestion and may show signs of cardiomegaly.[17]

Echocardiography

An echocardiogram should be performed to assess the left ventricular size, any wall motion abnormality, and systolic and diastolic function. It is important to look for any valvular pathology, left atrial size, right ventricular size, and systolic function.[17]

Treatment / Management

Patients presenting with alcohol intoxication or with symptoms of alcohol withdrawal should be given supportive treatment. This may include but is not limited to intravenous hydration, electrolytes replacement, vitamin replacement (especially thiamine and B-complex), and suppression of withdrawal signs and symptoms using clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol (CIWA) protocol.[20][21](B3)

Patients presenting to the emergency department with sustained tachyarrythmias should be observed using continuous telemetry monitoring. In most cases, observation and monitoring are sufficient.

If there are signs of clinical instability due to sustained tachyarrhythmias, synchronized cardioversion should be considered. These clinical signs include hypotension, altered mental status, clinical signs of shock, ischemic chest discomfort, or acute heart failure. Moderate sedation should be provided before performing synchronized cardioversion.[22]

In stable patients with diagnosed atrial fibrillation, treatment is focused on symptom control either by rate control strategy or rhythm control strategy and systemic thromboembolism prophylaxis.[17] In more than 90% of cases, alcohol-induced atrial fibrillation seems to terminate spontaneously 12 to 24 hours after presentation.[1][23](A1)

Therefore if not clinically unstable, the atrial fibrillation treatment strategy should be focused on achieving adequate rate control without causing hypotension. While there is no definitive consensus on the optimal heart rate to target, setting a goal based on symptoms is deemed appropriate. For example, in a symptomatic patient, a heart rate of less than 85 beats per minute may be considered reasonable, whereas a more flexible heart rate target may be appropriate for an asymptomatic patient.

Atrioventricular (AV) nodal blocking agents like cardioselective beta-blockers (carvedilol, metoprolol, bisoprolol) and non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (CCBs) can be used. Digoxin is a third-line option and is rarely used.

Long-term anticoagulation is indicated in atrial fibrillation for thromboembolism prophylaxis. It is important to exercise caution regarding anticoagulation use in alcoholic patients as they may have nutritional anemia or thrombocytopenia. They may also have acute or chronic trauma on presentation. Unless the patient has high-risk features like a prior stroke or any other indication for systemic anticoagulation, it may be appropriate to defer anticoagulation therapy until the patient has recovered from the acute presentation.[23](B2)

Though it is believed that alcohol alcohol-induced atrial fibrillation self-terminates, it is also seen that approximately 20% to 30% will recur within 12 months.[23] Further, it should be noted that the most recent guidelines from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) do not recognize "reversible" causes as sufficient reasons to forego anticoagulation for stroke risk reduction.[24] Guidelines recommend initiating systemic anticoagulation after shared decision-making between the patient and the physician. The decision should be guided by using the CHA2DS2VASc score and HAS-BLED score.[17](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

- Alcohol use disorder

- Arrhythmia

- Pulmonary embolism

- Community-acquired Pneumonia

- Acute Coronary Syndrome

- Dilated cardiomyopathy

- Thyrotoxicosis

- Substance abuse/drug abuse (cocaine, amphetamines)

Prognosis

The prognosis of holiday heart syndrome varies depending on the presence of any underlying cardiac disease. Chronic alcohol use raises the risk of arrhythmia, cardiomyopathy, and chronic liver disease. It should be noted that although the majority (>90%) of alcohol-related atrial fibrillation cases resolve spontaneously, approximately 20% to 30% may recur within 12 months.[23] When considering the atrial fibrillation subtype, moderate to heavy alcohol consumption is the most robust predictor of progression from paroxysmal atrial fibrillation to persistent atrial fibrillation.[25]

Complications

Complications of holiday heart syndrome include:

- Life-threatening arrhythmias

- Development of persistent and chronic atrial fibrillation

- Development of Dilated cardiomyopathy and congestive heart failure

- Embolic stroke and systemic thromboembolism

- Community-acquired pneumonia

- Death

Consultations

It is recommended that the patient undergo an initial consultation with a cardiologist. Subsequently, the patient may require the clinical expertise of an electrophysiologist if the patient has persistent and symptomatic arrhythmias, which may require ablative therapies.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients avoid significant physical exertion after an episode of alcohol-related arrhythmia. Excessive catecholamine release can trigger recurrent episodes in some cases. Most patients without underlying heart disease (normal electrocardiogram and echocardiogram) can gradually resume their normal physical activity within a few days.

Patients should be counseled that there is no recommended "safe" dosage of alcohol to prevent the occurrence of atrial fibrillation. In general, it is advisable to avoid alcohol consumption, particularly in light of the increased risk of atrial fibrillation.

Patients finding it difficult to quit alcohol should be provided with pharmacological and nonpharmacological resources. Referrals can be provided to deaddiction clinics and local support groups (alcoholic anonyms).

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing holiday heart syndrome requires an interprofessional team of healthcare professionals that includes a nurse, laboratory technologist, pharmacist, and a number of physicians in different specialties, including psychiatry and cardiology. Without proper management, the morbidity and mortality from holiday heart syndrome are high. The moment the triage nurse has admitted a patient with an arrhythmia and excessive alcohol use, the emergency department clinician is responsible for coordinating the care, which includes the following:

- Ordering alcohol levels in blood and urine, or other metabolites

- Monitor the patient for signs and symptoms of respiratory depression, suicidal ideations, signs and symptoms of heart failure, and alcohol withdrawal

- Monitor and replete thiamine before giving glucose in patients with alcohol use disorder to avoid neurologic deficits

- Consult with the pharmacist about the initiation of CIWA protocol in at-risk individuals

- Consult with a pharmacist about starting a benzodiazepine if a tremor or seizure history is present

- Consult with a nutritionist if the patient appears malnourished

- Consult with a toxicologist and nephrologist on further management, which may include dialysis

- Consult with the cardiologist regarding arrhythmia management

- Consult with the intensivist about ICU care and monitoring while in the hospital

- Review medication reconciliation, as many drugs interact with alcohol

The management of holiday heart syndrome does not stop in the emergency department. Once the patient is stabilized, one has to determine how and why the patient ingested large amounts of alcohol. Consult with a mental health counselor if this was intentional and assess risk factors for self-harm. [Level 1] Further, the possibility of addiction and withdrawal symptoms is a consideration. Only by working as an interprofessional team can the morbidity of alcohol ingestion be decreased. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Voskoboinik A, Prabhu S, Ling LH, Kalman JM, Kistler PM. Alcohol and Atrial Fibrillation: A Sobering Review. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2016 Dec 13:68(23):2567-2576. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.074. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27931615]

Ettinger PO, Wu CF, De La Cruz C Jr, Weisse AB, Ahmed SS, Regan TJ. Arrhythmias and the "Holiday Heart": alcohol-associated cardiac rhythm disorders. American heart journal. 1978 May:95(5):555-62 [PubMed PMID: 636996]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceThornton JR. Atrial fibrillation in healthy non-alcoholic people after an alcoholic binge. Lancet (London, England). 1984 Nov 3:2(8410):1013-5 [PubMed PMID: 6149396]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGallagher C, Hendriks JML, Elliott AD, Wong CX, Rangnekar G, Middeldorp ME, Mahajan R, Lau DH, Sanders P. Alcohol and incident atrial fibrillation - A systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of cardiology. 2017 Nov 1:246():46-52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.05.133. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28867013]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKodama S, Saito K, Tanaka S, Horikawa C, Saito A, Heianza Y, Anasako Y, Nishigaki Y, Yachi Y, Iida KT, Ohashi Y, Yamada N, Sone H. Alcohol consumption and risk of atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011 Jan 25:57(4):427-36. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.08.641. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21251583]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMarcus GM, Vittinghoff E, Whitman IR, Joyce S, Yang V, Nah G, Gerstenfeld EP, Moss JD, Lee RJ, Lee BK, Tseng ZH, Vedantham V, Olgin JE, Scheinman MM, Hsia H, Gladstone R, Fan S, Lee E, Fang C, Ogomori K, Fatch R, Hahn JA. Acute Consumption of Alcohol and Discrete Atrial Fibrillation Events. Annals of internal medicine. 2021 Nov:174(11):1503-1509. doi: 10.7326/M21-0228. Epub 2021 Aug 31 [PubMed PMID: 34461028]

Lowenstein SR, Gabow PA, Cramer J, Oliva PB, Ratner K. The role of alcohol in new-onset atrial fibrillation. Archives of internal medicine. 1983 Oct:143(10):1882-5 [PubMed PMID: 6625772]

Hansson A, Madsen-Härdig B, Olsson SB. Arrhythmia-provoking factors and symptoms at the onset of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: a study based on interviews with 100 patients seeking hospital assistance. BMC cardiovascular disorders. 2004 Aug 3:4():13 [PubMed PMID: 15291967]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNoessler N, Schweintzger S, Kurath-Koller S. Holiday heart syndrome: an upcoming tachyarrhythmia in today's youth? Cardiology in the young. 2021 Jun:31(6):1054-1056. doi: 10.1017/S1047951121000329. Epub 2021 Feb 9 [PubMed PMID: 33557971]

Yan J, Thomson JK, Zhao W, Gao X, Huang F, Chen B, Liang Q, Song LS, Fill M, Ai X. Role of Stress Kinase JNK in Binge Alcohol-Evoked Atrial Arrhythmia. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018 Apr 3:71(13):1459-1470. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.01.060. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29598867]

Staerk L, Sherer JA, Ko D, Benjamin EJ, Helm RH. Atrial Fibrillation: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Outcomes. Circulation research. 2017 Apr 28:120(9):1501-1517. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.309732. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28450367]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAndrade J, Khairy P, Dobrev D, Nattel S. The clinical profile and pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation: relationships among clinical features, epidemiology, and mechanisms. Circulation research. 2014 Apr 25:114(9):1453-68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303211. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24763464]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKupari M. Drunkenness, hangover, and the heart. Acta medica Scandinavica. 1983:213(2):84-90 [PubMed PMID: 6837336]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMarcus GM, Dukes JW, Vittinghoff E, Nah G, Badhwar N, Moss JD, Lee RJ, Lee BK, Tseng ZH, Walters TE, Vedantham V, Gladstone R, Fan S, Lee E, Fang C, Ogomori K, Hue T, Olgin JE, Scheinman MM, Hsia H, Ramchandani VA, Gerstenfeld EP. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Intravenous Alcohol to Assess Changes in Atrial Electrophysiology. JACC. Clinical electrophysiology. 2021 May:7(5):662-670. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2020.11.026. Epub 2021 Jan 27 [PubMed PMID: 33516710]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRagland G. Electrolyte abnormalities in the alcoholic patient. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 1990 Nov:8(4):761-73 [PubMed PMID: 2226285]

Tonelo D, Providência R, Gonçalves L. Holiday heart syndrome revisited after 34 years. Arquivos brasileiros de cardiologia. 2013 Aug:101(2):183-9. doi: 10.5935/abc.20130153. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24030078]

January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, Chen LY, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC Jr, Ellinor PT, Ezekowitz MD, Field ME, Furie KL, Heidenreich PA, Murray KT, Shea JB, Tracy CM, Yancy CW. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society in Collaboration With the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2019 Jul 9:140(2):e125-e151. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000665. Epub 2019 Jan 28 [PubMed PMID: 30686041]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceElisaf M, Merkouropoulos M, Tsianos EV, Siamopoulos KC. Pathogenetic mechanisms of hypomagnesemia in alcoholic patients. Journal of trace elements in medicine and biology : organ of the Society for Minerals and Trace Elements (GMS). 1995 Dec:9(4):210-4 [PubMed PMID: 8808192]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBallard HS. The hematological complications of alcoholism. Alcohol health and research world. 1997:21(1):42-52 [PubMed PMID: 15706762]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePiccioni A, Tarli C, Cardone S, Brigida M, D'Addio S, Covino M, Zanza C, Merra G, Ojetti V, Gasbarrini A, Addolorato G, Franceschi F. Role of first aid in the management of acute alcohol intoxication: a narrative review. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences. 2020 Sep:24(17):9121-9128. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202009_22859. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32965003]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKnight E, Lappalainen L. Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol-Revised might be an unreliable tool in the management of alcohol withdrawal. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien. 2017 Sep:63(9):691-695 [PubMed PMID: 28904034]

Craig-Brangan KJ, Day MP. Update: 2017/2018 AHA BLS, ACLS, and PALS guidelines. Nursing. 2019 Feb:49(2):46-49. doi: 10.1097/01.NURSE.0000552705.65749.a0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30676559]

Krishnamoorthy S, Lip GY, Lane DA. Alcohol and illicit drug use as precipitants of atrial fibrillation in young adults: a case series and literature review. The American journal of medicine. 2009 Sep:122(9):851-856.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.02.012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19699381]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJanuary CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, Calkins H, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC Jr, Conti JB, Ellinor PT, Ezekowitz MD, Field ME, Murray KT, Sacco RL, Stevenson WG, Tchou PJ, Tracy CM, Yancy CW, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014 Dec 2:64(21):e1-76. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.022. Epub 2014 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 24685669]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRuigómez A, Johansson S, Wallander MA, García Rodríguez LA. Predictors and prognosis of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in general practice in the UK. BMC cardiovascular disorders. 2005 Jul 11:5():20 [PubMed PMID: 16008832]