Introduction

Hydatiform mole (also known as molar pregnancy) is a subcategory of diseases under gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD), which originates from the placenta and can metastasize. It is unique because the tumor originates from gestational tissue rather than from maternal tissue. Other forms of gestational trophoblastic disease include gestational choriocarcinoma (which can be extremely malignant and invasive) and placental site trophoblastic tumors. Hydatiform mole (HM) is categorized as a complete and partial mole and is usually considered the noninvasive form of gestational trophoblastic disease. Although hydatiform moles are usually considered benign, they are premalignant and do have the potential to become malignant and invasive.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

As described previously, hydatiform moles are divided into complete and partial moles. Complete mole is the most common type and does not contain fetal parts, whereas in a partial mole there might be identifiable fetal residues. Complete moles are typically diploid, whereas partial moles are triploid. Complete moles tend to cause higher levels of the human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which is one of the main clinical features of this process. In complete moles, the karyotype is 46,XX 90% of the time and 46,XY 10% of the time. It arises when an enucleated egg is fertilized either by two sperms or by a haploid sperm that then duplicates and therefore, only paternal DNA is expressed. On the other hand, in partial moles, the karyotype is 90% of the time triploid and either 69,XXX or 69,XXY. This karyotype arises when a normal sperm subsequently fertilizes haploid ovum duplicates and or when two sperms fertilize a haploid ovum. In partial moles, both maternal and paternal DNA is expressed.[4][5][6]

Epidemiology

There is a very low frequency of hydatiform moles. In North America and Europe, the frequency has been described as 60 to 120/100,000 pregnancies for hydatiform moles. The frequency has been shown to be higher in other countries of the world. Certain risk factors increase the prevalence of molar pregnancies:

-

Extremes of maternal age:

-

Greater than 35 years old carries a five to ten-fold increased risk risk

-

Early teenage years, usually less than 20 years old

-

-

Previous molar pregnancy increases the risk 1% to 2% for future pregnancies

- Women with previous spontaneous abortions or infertilities

-

Dietary factors including patients that have diets deficient in carotene (vitamin A precursor) and animal fats

-

Smoking

Pathophysiology

As described previously, hydatiform moles arise from gestational tissue. In complete hydatidiform mole, there is no fetal tissue present; in partial hydatiform moles, there is some residual fetal tissue. Both are due to the over-proliferation of chorionic villi. It is still unclear if the trophoblastic transformation causes vascular obliteration and fetal death or, in another theory, a spontaneous stillbirth causes villous dysmorphism and trophoblastic proliferation. Several studies [7][8][9][10][11] reveal a severe vasculogenic deficit in trophoblastic diseases, with significantly retarded angiogenesis in early complete mole, progressive accumulation of fluids, and subsequent formation of cystic spaces ("cistern"). In complete moles an enucleated egg is fertilized either by two sperm or, more commonly, monospermic arising from a haploid sperm which endoreduplicates, resulting in only paternal DNA being expressed; this aberration lacks mitochondria, as mitochondrial DNA is maternally derived. Conversely, in a partial hydatiform mole, a haploid ovum either duplicates and fertilized by normal sperm, or a haploid ovum is fertilized by two sperm, resulting in both the expression of both maternal and paternal DNA.[12] In brief, complete moles are diploid (46,XX; 46,XY) while most partial moles are triploid (69,XXY; XXX; XYY). Triploid or tetraploid complete moles are androgenetic (since they lack maternal chromosomes) while tetraploid partial moles have maternal contributions. Hydatiform mole is characterized by chromosomal abnormalities, which allow for malignant transformation in choriocarcinoma. The most common alteration leading to malignant transformation are the activation of oncogenes, inactivation of tumor suppressors, and the alteration of telomerase regulation.

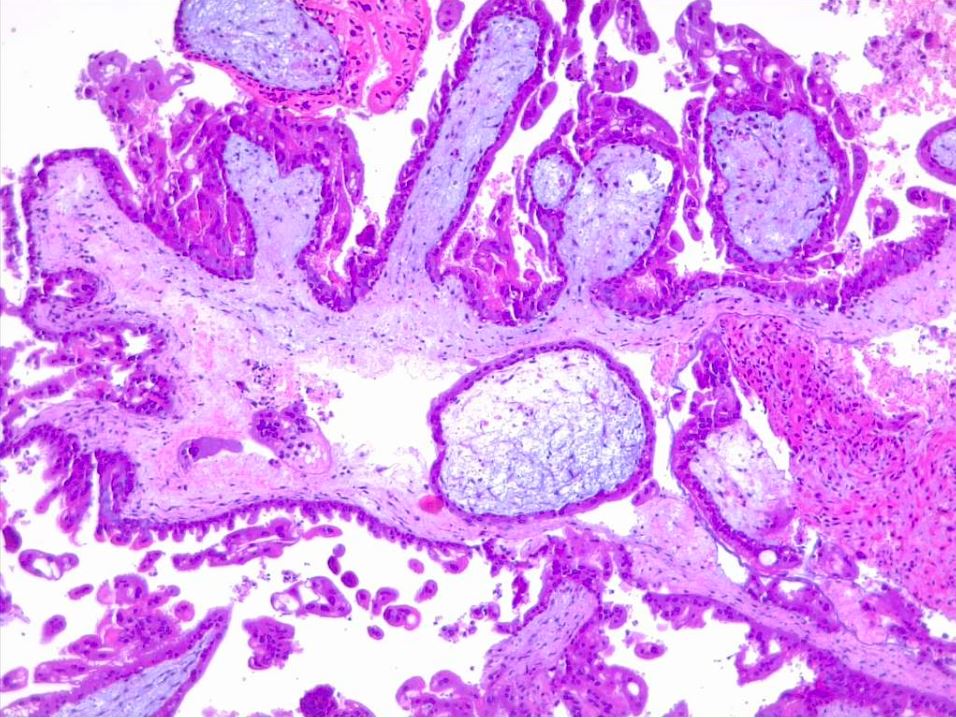

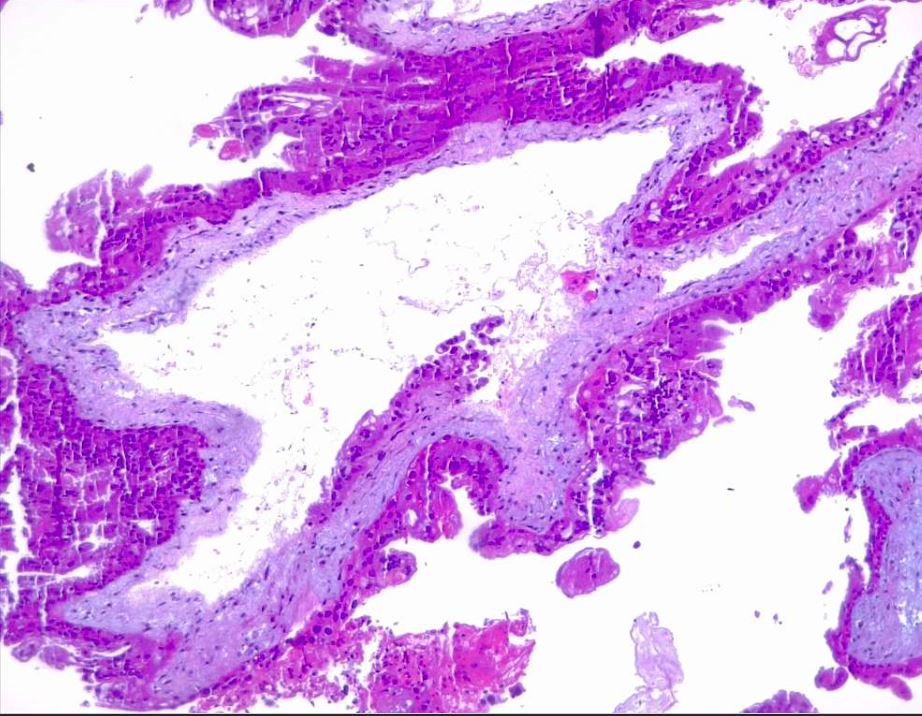

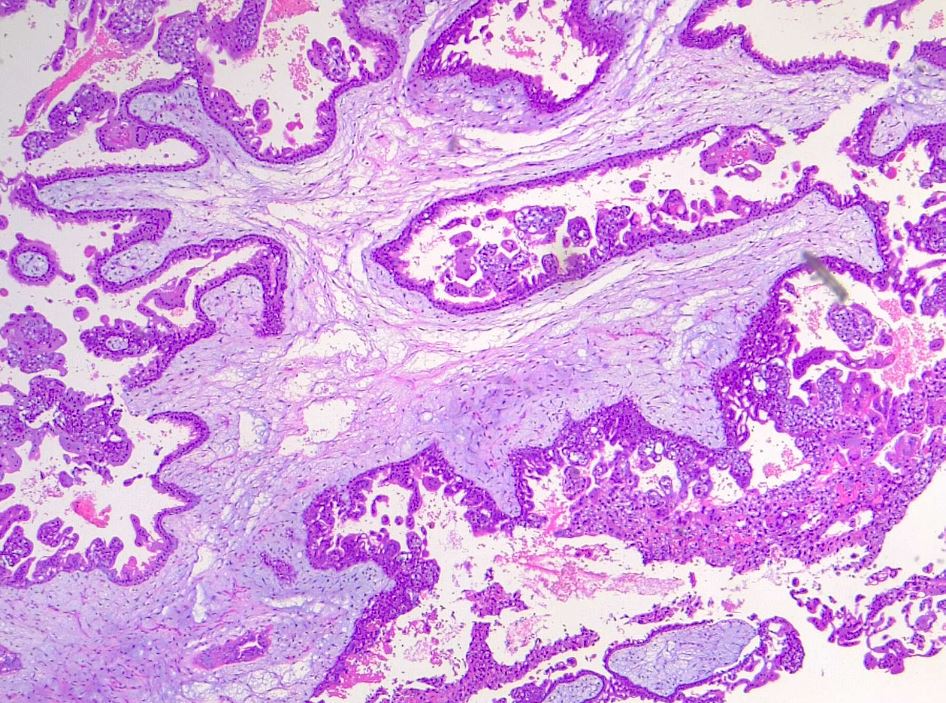

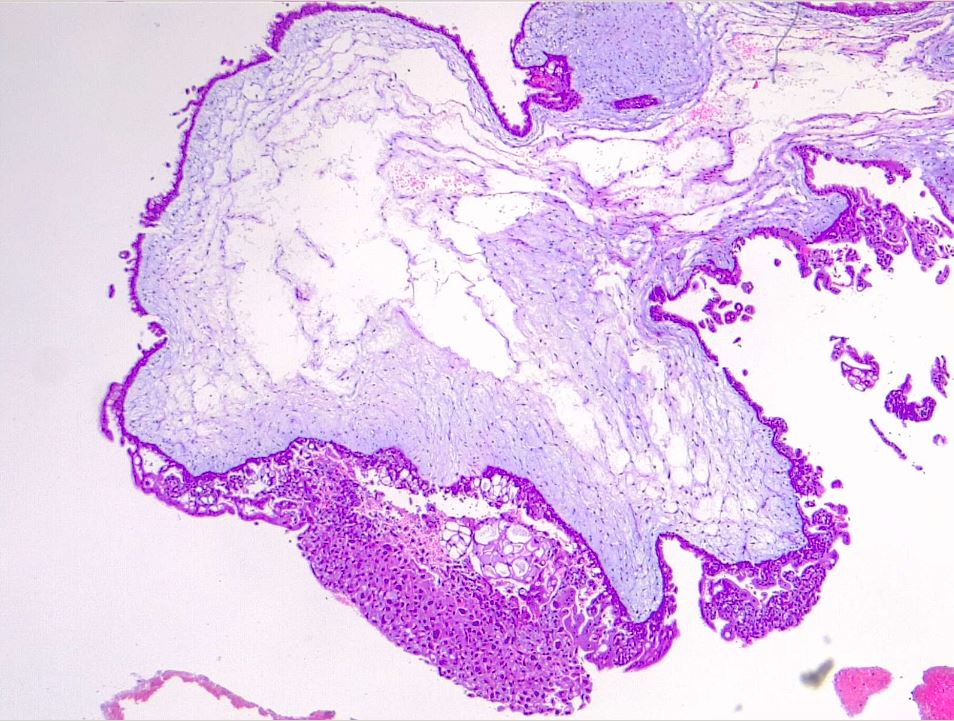

Histopathology

Hydatiform mole is characterized by an overgrown villous trophoblast with cystic "swollen" villi. Macroscopically can be visible, the second trimester, as clusters of vesicles (similar to small grapes) developed from the transformation of chorionic villi. Complete mole differs from partial mole, in cytogenetic and microscopical appearance. Important is a complete lack of embryonic/fetal tissue in complete moles and the presence of-of embryonic tissue in partial moles.

Microscopically, a complete mole has markedly hydropic and deformed chorionic villi with the formation of "cisterns" containing stromal fluid; there is a peripheral proliferation of both cytotrophoblast and syncytiotrophoblast, arranged in lace-like structures, papillary formation, or circumferential. In normal early placenta the cytotrophoblast and syncytiotrophoblast are polarized. There is the absence of fetal stromal blood vessels. An immature vascular network is otherwise present, positive for CD31, with dysmorphic features such as a complete lack of lumen. In partial mole there are hydropic chorionic villi surrounded by hyperplastic trophoblasts with variable degrees of central cistern formation, with an irregular maze-like pattern; also, there are normal chorionic villi and embryonic or fetal tissue mixed with hydropic villi. There are recognizable fetal blood vessels containing fetal red blood cells. The curettage material should be examined carefully, especially in first trimester pregnancies, and if a partial mole is suspected the whole specimen should be examined. The main differential diagnosis is with a hydropic abortion, where the main clue is the presence of villous edema only with microscopical evaluation and lacks cistern formation or trophoblastic proliferation. A pitfall in hydropic abortion is the presence of polar stratification of anchoring trophoblast in a first-trimester placenta. The villous size in hydropic abortion ranges from small, to medium and large.

An important marker that aids in the diagnosis of the complete mole is the presence or absence of p57 in immunohistochemistry. This marker is a paternal-imprint inhibitor gene so its expression implies the maternal contribution; in brief, the absence of p57 expression supports the diagnosis of androgenetic gestational disease with complete mole [13][14][15]. Moles also express p53, p21, cyclin E, and MCM7.

History and Physical

The presentation of the hydatiform mole is somewhat different in a complete mole versus a partial mole. In fact, most partial moles are diagnosed as spontaneous abortions that are later discovered after a pathology report is obtained from the fetal tissue.

Since the advent of ultrasonography, the diagnosis of complete molar pregnancies has increased in the early stages of pregnancy, mainly during the first trimester. The most common symptom (in one study as high as 84% of patients) of a complete mole is vaginal bleeding in the first trimester, which is normally due to the molar tissue separating from the decidua, resulting in bleeding. The typical buzzword appearance of vaginal bleeding is described as a "prune juice" appearance. This is secondary to the accumulated blood products in the uterine cavity and resultant oxidation and liquefaction of that blood. Another symptom of a complete molar pregnancy is hyperemesis (severe nausea and vomiting), which is due to the high level of the hCG hormone circulating in the bloodstream. Some patients also endorse passage of vaginal tissue described as grape-like clusters or vesicles. Late findings of the disease (after the first trimester around 14 to 16 weeks of pregnancy) including signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism, including tachycardia and tremors, again caused by the high levels of circulating hCG. Other late sequelae are pre-eclampsia, which is pregnancy-induced hypertension and proteinuria and/or end-organ dysfunction occurring typically after 34 weeks of pregnancy. When a patient less than 20 weeks pregnant presents with signs and symptoms of pre-eclampsia, a complete molar pregnancy should highly be suspected. In very advanced cases, patients present with severe respiratory distress possible from embolism of the trophoblastic tissue into the lungs.

The presentation of a partial hydatiform mole is usually less dramatic than that of a complete mole. These patients typically present as described before with symptoms similar to a threatened or spontaneous abortion, including vaginal bleeding. Since partial hydatiform moles have fetal tissue, on examination, these patients may have fetal heart tones evident on Doppler.

On physical exam, in more than 50% of cases, uterine size discrepancy and date discrepancy usually takes place. In a complete mole, the uterus is usually larger than the expected gestational date of the pregnancy, whereas, in partial moles, the uterus can be smaller than the suggested date.

Evaluation

In a pregnant patient with vaginal bleeding, one should always obtain a serum quantitative hCG level and the patient's blood type. In hydatiform moles, the serum hCG levels are typically much higher than patients of the same gestational date in a normal pregnancy or ectopic pregnancy. Complete moles tend to have very high levels of serum hCG, typically greater than 100,000, whereas partial moles may be within the normal range for gestational age or even lower than expected. Blood type is important because most patients with complete or partial hydatiform moles present with vaginal bleeding. Therefore, Rh antibody screening needs to be performed to determine whether anti-D immunoglobulin needs to be administered if the patient is Rh(D) negative. Other laboratory tests include:

Complete blood count (CBC) (to evaluate for anemia and thrombocytopenia)

BMP (to evaluate for electrolyte imbalance and renal insufficiency)

Thyroid panel (if signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism present)

Liver function tests and urinalysis (if pre-eclampsia is suspected to evaluate for transaminitis and proteinuria)

Coagulation profile including PT/INR to evaluate for disseminated intravascular coagulation in severe cases.

The imaging of choice in a suspected hydatiform mole is a pelvic ultrasound. In a complete mole, the ultrasound findings include a heterogeneous mass in the uterine cavity with multiple anechoic spaces, most commonly referred to as a "snowstorm" appearance. These small cystic areas are typically the hydropic villi described previously in the histopathology section. Furthermore, there is the absence of an embryo or fetus, and no amniotic fluid is present. In a partial mole, there typically is the finding of a fetus which may be viable, the presence of amniotic fluid, and the placenta appears to have enlarged, cystic spaces (often described as "Swiss cheese" appearance). In one study, it was noted that partial moles were diagnosed as a missed or incomplete abortion in 15% to 60% of cases.

If a molar pregnancy is diagnosed, the next step is typically a CT scan and PET scan to stage the disease. Furthermore, a chest x-ray should be obtained if the patient's initial symptoms included any signs of respiratory distress or increased breathing to evaluate for pulmonary edema.[16][17][18]

Treatment / Management

In the emergency department, the priority is clinical stabilization. If there is any evidence of respiratory distress and pulmonary edema, non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (such as BiPAP) or mechanical ventilation should be started. Furthermore, if there are signs of symptoms of eclampsia (late stage of pre-eclampsia), including seizures, one should initiate appropriate management, including benzodiazepines and magnesium sulfate administration. If the patient has signs of pre-eclampsia, urgent blood pressure control is necessary with medications such as hydralazine and labetalol. If there are signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism, practitioners should initiate proper treatment, including beta-blockers, and monitor for thyroid storm. If severe anemia is present, the clinician should consider a blood transfusion. As discussed earlier, if a patient is Rh(D) negative, the physician should administer the anti-D immunoglobulin.

Once the patient is stabilized, an emergent obstetrics consultation is necessary for the likely need for dilation and curettage (D and C). In patients with advanced maternal age typically greater than 40 years old and those who have completed childbearing, hysterectomy is often performed instead of a D and C. Hysterectomy, however, does not completely eliminate the risk of metastatic disease. After the evacuation of the molar pregnancy, the hCG levels should be monitored; if remain elevated, there is evidence of persistent or invasive disease requiring at times chemotherapy. A gynecological oncologist consultation is usually necessary in these cases to guide therapy.

Differential Diagnosis

- Androgenetic/biparental mosaic conceptions

- Abnormal villous morphology

- Early abortus with trophoblastic hyperplasia

- Hydropic abortus

- Hyperemesis gravidarum

- Hypertension

- Hyperthyroidism

- Malignant hypertension

- Placental mesenchymal dysplasia

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A molar pregnancy is best managed with an interprofessional team. Once molar pregnancy is diagnosed and an obstetric/gynecology consultation is obtained, patients are typically admitted to the hospital for surgery. Weekly serum hCG levels are obtained after surgery until an undetectable level of hCG is reached (usually done in an outpatient setting). Patients with previous molar pregnancy are advised to use reliable contraception to avoid a new pregnancy. It could conflict with weekly serum hCG level testing and make it impossible to determine the occurrence of invasive molar disease. The risk of invasive disease in a complete molar pregnancy is around 15% to 20%, and in a partial molar pregnancy is 1% to 5%.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Mittal S, Menon S. Interstitial pregnancy mimicking an invasive hydatidiform mole. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2019 May:220(5):501. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.10.024. Epub 2018 Oct 25 [PubMed PMID: 31079718]

Sarmadi S, Izadi-Mood N, Sanii S, Motevalli D. Inter-observer variability in the histologic criteria of diagnosis of hydatidiform moles. The Malaysian journal of pathology. 2019 Apr:41(1):15-24 [PubMed PMID: 31025633]

Ning F, Hou H, Morse AN, Lash GE. Understanding and management of gestational trophoblastic disease. F1000Research. 2019:8():. pii: F1000 Faculty Rev-428. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.14953.1. Epub 2019 Apr 10 [PubMed PMID: 31001418]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBraga A, Mora P, de Melo AC, Nogueira-Rodrigues A, Amim-Junior J, Rezende-Filho J, Seckl MJ. Challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia worldwide. World journal of clinical oncology. 2019 Feb 24:10(2):28-37. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v10.i2.28. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30815369]

Yuk JS, Baek JC, Park JE, Jo HC, Park JK, Cho IA. Incidence of gestational trophoblastic disease in South Korea: a longitudinal, population-based study. PeerJ. 2019:7():e6490. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6490. Epub 2019 Feb 20 [PubMed PMID: 30809458]

Li X, Xu Y, Liu Y, Cheng X, Wang X, Lu W, Xie X. The management of hydatidiform mole with lung nodule: a retrospective analysis in 53 patients. Journal of gynecologic oncology. 2019 Mar:30(2):e16. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2019.30.e16. Epub 2018 Nov 23 [PubMed PMID: 30740949]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKim MJ, Kim KR, Ro JY, Lage JM, Lee HI. Diagnostic and pathogenetic significance of increased stromal apoptosis and incomplete vasculogenesis in complete hydatidiform moles in very early pregnancy periods. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2006 Mar:30(3):362-9 [PubMed PMID: 16538057]

Lisman BA, Boer K, Bleker OP, van Wely M, Exalto N. Vasculogenesis in complete and partial hydatidiform mole pregnancies studied with CD34 immunohistochemistry. Human reproduction (Oxford, England). 2005 Aug:20(8):2334-9 [PubMed PMID: 15878926]

Kim KR, Park BH, Hong YO, Kwon HC, Robboy SJ. The villous stromal constituents of complete hydatidiform mole differ histologically in very early pregnancy from the normally developing placenta. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2009 Feb:33(2):176-85. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31817fada1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18936691]

Novac L, Niculescu M, Manolea MM, Iliescu D, Georgescu CV, Comănescu A, Cernea N, Enache A. The vasculogenesis--a possible histological identification criterion for the molar pregnancy. Romanian journal of morphology and embryology = Revue roumaine de morphologie et embryologie. 2011:52(1):61-7 [PubMed PMID: 21424033]

Hussein MR. Analysis of the vascular profile and CD99 protein expression in the partial and complete hydatidiform moles using quantitative CD34 immunohistochemistry. Experimental and molecular pathology. 2010 Dec:89(3):343-50. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2010.07.002. Epub 2010 Jul 12 [PubMed PMID: 20630481]

Kar A, Mishra C, Biswal P, Kar T, Panda S, Naik S. Differential expression of cyclin E, p63, and Ki-67 in gestational trophoblastic disease and its role in diagnosis and management: A prospective case-control study. Indian journal of pathology & microbiology. 2019 Jan-Mar:62(1):54-60. doi: 10.4103/IJPM.IJPM_82_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30706860]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGiacometti C, Bellan E, Ambrosi A, Dei Tos AP, Cassaro M, Ludwig K. "While there is p57, there is hope." The past and the present of diagnosis in first trimester abortions: Diagnostic dilemmas and algorithmic approaches. A review. Placenta. 2021 Dec:116():31-37. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2021.02.010. Epub 2021 Feb 25 [PubMed PMID: 33714612]

Xing D, Adams E, Huang J, Ronnett BM. Refined diagnosis of hydatidiform moles with p57 immunohistochemistry and molecular genotyping: updated analysis of a prospective series of 2217 cases. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2021 May:34(5):961-982. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-00691-9. Epub 2020 Oct 6 [PubMed PMID: 33024305]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTakahashi S, Okae H, Kobayashi N, Kitamura A, Kumada K, Yaegashi N, Arima T. Loss of p57(KIP2) expression confers resistance to contact inhibition in human androgenetic trophoblast stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2019 Dec 26:116(52):26606-26613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1916019116. Epub 2019 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 31792181]

Ross JA, Unipan A, Clarke J, Magee C, Johns J. Ultrasound diagnosis of molar pregnancy. Ultrasound (Leeds, England). 2018 Aug:26(3):153-159. doi: 10.1177/1742271X17748514. Epub 2018 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 30147739]

Heller DS. Update on the pathology of gestational trophoblastic disease. APMIS : acta pathologica, microbiologica, et immunologica Scandinavica. 2018 Jul:126(7):647-654. doi: 10.1111/apm.12786. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30129126]

Ling C, Zhao J, Qi X. Partial molar pregnancy in the cesarean scar: A case report and literature review. Medicine. 2018 Jun:97(26):e11312. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011312. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29953018]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence