Introduction

Hyperammonemia is a metabolic condition characterized by the raised levels of ammonia, a nitrogen-containing compound. Normal levels of ammonia in the body vary according to age. Hyperammonemia can result from various congenital and acquired conditions in which it may be the principal toxin. Hyperammonemia may also occur as a part of other disorders that involve various other metabolic abnormalities. Normally, ammonia is produced in the colon and small intestine from where it is transported to the liver to be converted to urea via the urea cycle. Urea, a water-soluble compound, can then be excreted via the kidneys. Ammonia levels rise if the liver is unable to metabolize this toxic compound as a result of an enzymatic defect or hepatocellular damage. The levels may also rise if portal blood is diverted to the systemic circulation, bypassing the liver, or there is increased production of ammonia due to an infection with certain microorganisms.[1][2] Hyperammonemia in adults is most commonly related to cirrhotic liver disease in 90% of the cases. This metabolic abnormality, however, can be seen in numerous other disorders that need to be understood. Ammonia is a potent neurotoxin, and elevated levels in the blood can cause neurological signs and symptoms that may be acute or chronic, depending on the underlying abnormality. Hyperammonemia should be recognized early and treated immediately to prevent the development of life-threatening complications such as cerebral edema and brain herniation. Treatment strategies vary according to etiology.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of hyperammonemia is vast. It is a part of numerous disorders that can be classified as congenital or acquired. The acquired disorders can further be classified as hyperammonemia due to hepatic causes and non-hepatic causes (causes other than a liver disease). Congenital disorders involving enzymatic defects include urea cycle defects, organic acidemias, congenital lactic acidosis, fatty acid oxidation defect, and dibasic amino acid deficiencies. Other disorders include transient hyperammonemia of the newborn, neonatal Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, and severe perinatal asphyxia.

Urea Cycle Enzyme Defects

The urea cycle is an energy-dependent process responsible for the conversion of toxic ammonia into urea, which can then be excreted. Five major steps are involved, each requiring a different enzyme. These include N-acetyl-glutamate synthase, carbamoyl phosphate synthetase (CPS), ornithine transcarbamylase, argininosuccinate synthetase (AS), argininosuccinic acid lyase (AL), and arginase.[3] A defect in any of these enzymes results in impaired function of the urea cycle, leading to the accumulation of ammonia. All of the defects are autosomal recessive, except for ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency, which is X-linked recessive. This is also the most common type of urea cycle disorder, and its prevalence is estimated to be 1:140000.[4] Females who are heterozygous for this defect, and males with some residual function of the enzyme can present later in life. Argininosuccinic acid lyase deficiency is the second most common defect and sometimes is linked to trichorrhexis nodosa. Defects in carbamoyl phosphate synthetase (CPS) and argininosuccinate synthetase (ASS) result in hyperammonemia that presents in the first 24 to 48 hours of life. Hyperammonemia is mild in arginase deficiency, and the associated neuronal damage is due to elevated levels of arginine.

Other enzymatic defects causing hyperammonemia are associated with additional metabolic abnormalities. Ketosis and acidosis are associated with organic acidemias such as isovaleric acidemia. Elevated pyruvate and lactate levels in congenital lactic acidosis and severe hypoglycemia in acyl CoA dehydrogenase deficiency are seen along with hyperammonemia.

Transient hyperammonemia of infancy is possibly due to the slow maturation of the urea cycle function seen in premature infants. It usually presents with signs and symptoms of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy and intracranial hypertension within the first 24 to 48 hours of life. Severe perinatal asphyxia or neonatal HSV infection may also result in elevated ammonia levels.

An acquired disease-causing hyperammonemia in children is Reye syndrome, a childhood disorder that occurs most commonly after influenza or varicella infection and ingestion of aspirin. Hyperammonemia is coupled with elevated liver enzymes and lactic acidosis. Hepatomegaly is usually seen on examination. Liver Disease

Hepatic encephalopathy is a syndrome of neuropsychiatric manifestations in patients with liver disease, and one of the mechanisms of its development is hypothesized to be hyperammonemia. 10% of the patients with hepatic encephalopathy, however, do not have raised levels of ammonia. Hepatic encephalopathy can be categorized into three main types depending on the underlying cause. They are:

- Type A hepatic encephalopathy: acute liver failure due to viral hepatitis, ischemic hepatitis, and ingestion of hepatotoxins. This usually presents with features of acute hepatic encephalopathy along with hepatic synthetic dysfunction.

- Type B encephalopathy: portosystemic shunts in patients with no underlying cirrhosis or liver disease. It may be congenital (a rare disorder) or artificially created (for portal vein thrombosis) and can result in hyperammonemia as the blood bypasses the liver.[5] These conditions can also give rise to features of encephalopathy.

- Type C hepatic encephalopathy: cirrhosis and portal hypertension due to chronic Hepatitis B or C virus, biliary atresia, alpha 1 antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson disease, and cystic fibrosis.

Encephalopathy can be acutely precipitated by renal failure, gastrointestinal bleed, or infection.

Causes of noncirrhotic hyperammonemia in adults include:

- Hematological disorders: multiple myeloma (plasma cells have increased amino acid metabolism) and acute leukemia.

- Infections: infections with urease-producing organisms such as Proteus mirabilis, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella may result in severe hyperammonemia in children with congenital defects of the urinary tract and the elderly with urinary tract infections leading to urinary retention.[6] These bacteria utilize the enzyme urease to hydrolyze urea to ammonium ions (NH), thus causing an elevation in the urinary pH. Ammonium ions change into lipophilic ammonia (NH) in the alkaline urine, and this compound is easily transferred to the venous plexus around the bladder. This can lead to hyperammonemia that may be severe enough to lead to encephalopathy or coma.[6]

- Unmasked urea cycle defects: As mentioned previously, females who are heterozygous for ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency and males with some residual function of the enzyme can present later in life. They can develop clinical features of hyperammonemia in stressful situations such as increased muscle catabolism due to seizures and starvation, increased protein load delivered in total parenteral nutrition, gastrointestinal bleeding, and infections.[7][8][7] Late presentations are fairly common in this defect.

- Drugs: Several drugs may give rise to hyperammonemia. Valproic acid is thought to cause hyperammonemia by inhibiting glutamate uptake by astrocytes.[9] This effect is more likely to be seen in patients with masked urea cycle defects. Some cases of topiramate/valproate-induced hyperammonemic encephalopathy have been reported.[10] Other drugs associated include carbamazepine, salicylates, and sulfadiazine.

Liver disease is not present in some patients with portosystemic shunts, as described above. The term ‘Type B hepatic encephalopathy,’ however, is used to describe the neuropsychiatric features seen in the patients with this abnormality.

Epidemiology

Hyperammonemia occurs as a result of multiple disorders, hence accurate data on its incidence is difficult to obtain. A gross estimate on the incidence of urea cycle disorders is 1 in 250,000 live births in the United States and 1 in 440,000 live births internationally.[11]

Pathophysiology

Ammonia is produced in various organs of the body by different mechanisms:

- Colon: Bacterial metabolism of protein and urea

- Small intestine: Glutamate degradation by bacteria

- Skeletal muscle: Amino acid transamination and the purine-nucleotide cycle

Abnormalities in the urea cycle or liver disorders may lead to increased levels of ammonia, which is then transported to the brain, skeletal muscle, and kidneys for elimination.

Role of Ammonia in Neurotoxicity

The exact mechanism by which ammonia results in CNS damage has not been established. It has been hypothesized that various alterations in the neurotransmitter system are responsible for the neuronal damage seen in both acute and chronic hyperammonemia. Animal studies have shown that acute ammonia intoxication in vitro results in elevated extracellular levels of glutamate in the brain. This results in activation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, which causes decreased phosphorylation of protein kinase C that results in the activation of Na/K-ATPase. The resultant ATP depletion is responsible for ammonia toxicity and is the most probable cause of seizures in acute hyperammonemia.[12]

Another consequence of acute hyperammonemia is cerebral edema. This occurs primarily due to the swelling of astrocytes, which are the only cells involved in ammonia detoxification in the brain. Proposed mechanisms for astrocyte swelling include altered water and K+ metabolism in the astrocytes, activation of tumor suppressor protein p53, increased uptake of certain compounds including pyruvate, lactate, and glutamine and decreased uptake of ketone bodies, glutamate, and free glucose. Cerebral edema leads to raised intracranial pressure, which may result in brain herniation.[13]

Chronic hyperammonemia results in two major pathological changes, both of which result in increased inhibitory neurotransmission.

- Increased extra-synaptic glutamate accumulation leading to the downregulation of glutamate receptors. Changes in the glutamate-nitric oxide-cGMP pathway resulting in impaired signal transmission in the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. This contributes to the cognitive dysfunction seen in hepatic encephalopathy.[12]

- Benzodiazepine receptor overstimulation from endogenous benzodiazepines and neurosteroids, resulting in an increased GABAergic tone

Ammonia increases the transport of tryptophan, an aromatic amino acid, across the blood-brain barrier. The resultant increased serotonin levels in the brain are responsible for anorexia commonly seen in chronic hyperammonemia.

History and Physical

History

Hyperammonemia mainly presents with neurological signs and symptoms due to its neurotoxic effects. Early-onset hyperammonemia is seen in neonates at 24-72 hours of life. The neonate becomes symptomatic as ammonia levels rise above 100-150 micromol/L. The family usually gives a history of non-specific symptoms, including lethargy, irritability, and vomiting. As the levels rise, the child may develop hyperventilation and grunting as the ammonium ion stimulates the medullary center of the brain responsible for controlling respiration.

Late-onset hyperammonemia presents later in life and occurs as a result of multiple congenital and acquired disorders, as described above. Symptoms include irritability, headache, vomiting, ataxia, and gait abnormalities in the milder cases. Seizures, encephalopathy, coma, and even death can occur in cases with ammonia levels greater than 200 micromol/L.[14] Patients with partial defects in urea cycle enzymes develop symptoms only during stressful periods e.g., starvation, pregnancy, surgery, etc. Symptoms may also be precipitated due to an increase in protein intake, constipation, aggressive diuresis, use of opioids, or infections like spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Patients may develop intellectual disability, behavioral and psychiatric symptoms in chronic hyperammonemia. This has been linked to glutamine levels in the brain.[15]

Physical Exam

Physical exam findings are usually non-specific, including increased respiratory rate and dehydration due to vomiting. Neurological examination may reveal impaired concentration and coordination, slurred speech, disorientation, and hand tremors. Examination findings specific to the underlying disorder may also be seen. An odor of ‘sweaty feet’ may be present in isovaleric acidemia, and fragile hair may be observed in argininosuccinic acid lyase deficiency.

Five grades of hepatic encephalopathy have been used to describe both acute and chronic clinical manifestations:

- Grade 0: subclinical or minimal hepatic encephalopathy categorized by minimal changes in concentration, memory, and intellectual function

- Grade 1: changes in sleep pattern, lack of awareness, and shortened attention span

- Grade 2: lethargy, apathy, changes in personality, asterixis, and slurred speech

- Grade 3: Somnolent but can be aroused, marked confusion, and disorientation of time and space

- Grade 4: Coma. The patient may or may not respond to painful stimuli.

In patients with hepatic encephalopathy due to cirrhosis, several physical examination findings due to hepatic dysfunction and portal hypertension, including jaundice, abdominal distension with shifting dullness, hepatomegaly, pedal edema, spider nevi, gynecomastia, and caput-medusae can also be appreciated.

Evaluation

Normal levels of ammonia vary according to age, being higher in newborns compared to older children or adults. In newborns, gestational and postnatal ages also affect the levels of ammonia.

Healthy term infants: 45±9 micromol/L; 80 to 90 micromol/L is considered to be the upper limit of normal.

Preterm infants: 71±26 micromol/L, decreasing to term levels in approximately seven days

Children older than 1 month: less than 50 micromol/L

Adults: less than 30 micromol/L

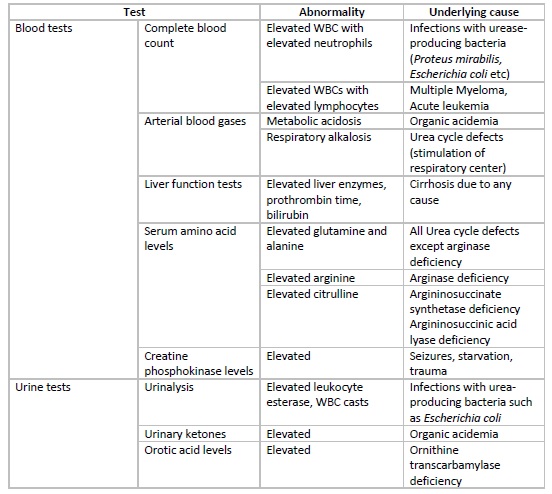

In the neonatal period, hyperammonemia presents with non-specific signs and symptoms, and thus important tests to rule out sepsis, meningitis, intracranial hemorrhage, and GI bleed should be considered. Raised levels of ammonia should prompt specific investigations including arterial blood gases, blood glucose, lactate and citrulline levels, plasma and urinary amino acids, urinary ketones, etc. Some additional tests that can be done for diagnosing urea cycle defects include specific enzyme assays on liver biopsy specimens or red blood cells and DNA mutation.

In patients with hepatic encephalopathy, liver function tests, including levels of liver enzymes and bilirubin and prothrombin time, are helpful to gauge the synthetic function of the liver. Specific tests to diagnose the underlying etiology of non-cirrhotic hyperammonemia should be considered if reasonable clinical suspicion is present.

Neuroimaging with CT scan or MRI can be helpful for diagnosis, although it will only show the effects ammonia has on the brain. In hyperammonemic encephalopathy, MRI shows diffusion restriction in the insular cortex and cingulate gyrus.[16] These changes may be reversible but may also lead to atrophy. In patients with chronic liver disease, cerebral atrophy with symmetric hyperintensities of the globus pallidus is seen. Asymmetric involvement of the thalami, parietal, occipital, temporal, and frontal cortices can also be seen.[17] The affected areas of the brain in neonates with congenital defects leading to hyperammonemia include the insular sulci and the lentiform nuclei. One reason for the different patterns of involvement in neonates could be that these areas are more metabolically active.[18] Some studies have shown that an increased severity or duration of hyperammonemic insult leads to a greater extent of abnormalities that can be witnessed on neuroimaging.[18]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of acute hyperammonemia focuses on decreasing the level of ammonia and controlling specific complications, including cerebral edema and intracranial hypertension. Inborn errors of metabolism may lead to neonatal-onset hyperammonemia or may present as intercurrent episodes of hyperammonemia. These require continual treatments targeted at the specific etiology. The treatment of hepatic encephalopathy differs from that of inborn errors of metabolism.

Treatment to Lower Ammonia

Neonates with inborn errors of metabolism may present with hyperammonemic coma, a serious condition requiring immediate intervention. All protein intake should be stopped, and calories should be provided using glucose solutions. Hemodialysis is preferred over peritoneal dialysis for the rapid removal of ammonia.[19][20] Continuous arteriovenous or venovenous hemofiltration can also be considered.[21] As the levels of ammonia fall, compounds that convert nitrogenous waste into products other than urea are used. These include sodium benzoate and phenylacetate in the intravenous forms.[20] Intravenous arginine should also be provided.(B2)

Patients with masked urea cycle defects develop hyperammonemia in conditions of increased stress and should be treated when levels rise greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal. Calories should be provided intravenously by glucose solutions, and all nitrogen intake should be stopped. Intravenous sodium benzoate and phenylacetate should be started. Dialysis should be considered only when ammonia levels do not fall after 8 hours of continual treatment.

Medical treatment for hepatic encephalopathy is targeted towards decreasing the production of ammonia in the gut. The established first-line therapy for encephalopathy is oral non-absorbable disaccharides, including lactulose and lactitol. These sugars work by decreasing the production and absorption of ammonia in the intestine.[22] They, however, do not affect mortality. The non-absorbable antibiotic, rifaximin, is also used as first-line therapy and is usually given along with the non-absorbable disaccharides.[23] (A1)

Management of Complications

Hypertonic saline is preferred over mannitol for the management of increased intracranial pressure due to cerebral edema.[24][25] Sedation with propofol and the use of hyperosmolar agents are considered effective for the management of hyperammonemia due to fulminant hepatic failure resulting in cerebral edema and raised intracranial pressure.[26] Corticosteroids induce a negative nitrogen balance and thus should be avoided in the treatment of raised intracranial pressure in neonatal-onset hyperammonemia. Valproic acid should not be used to treat seizures seen in hyperammonemia.[9](B3)

Dietary Management

It is logical to assume protein intake needs to be restricted in patients with hyperammonemia. Protein restriction is not recommended, specifically in patients with chronic liver disease as they are already malnourished, and the general consensus is to continue a normal intake of proteins. Some compounds may play a role in lowering ammonia and can be supplemented in the diet. L-carnitine can be used to decrease the frequency of attacks in patients with urea cycle defects.[9] L-ornithine-L-aspartate may be of use in hepatic encephalopathy as it increases ammonia metabolism in the muscle.[27] Arginine should be supplemented in the diet of patients with urea cycle defects as it becomes an essential amino acid.(A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Hyperammonemia is itself a condition that may result from a multitude of disorders, as described above. Laboratory and radiological investigations should be done to rule out CNS diseases with clinical findings resembling those seen in hyperammonemia. Examples include meningitis and sepsis in neonates and meningitis, encephalitis, brain tumors, and pseudotumor cerebri in adults.

Multiple disorders can present with hyperammonemia like picture but with ammonia levels within a normal range. Disorders of carbohydrate metabolism present with hypoglycemia and hyperuricemia. Ataxia, with genetic and biochemical defects, is caused by various hereditary defects affecting the CNS at multiple levels. Developmental delay and neuronal regression are frequently seen. Methylmalonic acidemia, an inherited disorder of amino acid metabolism with encephalopathy and stroke as a common presentation. Stroke is not seen in patients of hyperammonemia. Homocystinuria is a disorder of methionine metabolism that presents with features of stroke, ectopia lentis, and marfanoid habitus. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, diffuse hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, and seizure disorders may present with neuroimaging findings similar to that of hyperammonemia but occur due to other causes and usually do not have raised levels of ammonia.[17]

Prognosis

Prognosis depends on the underlying condition responsible for raised ammonia levels. For urea cycle defects, the 11-year-survival rate was reported to be 35% and 87% for patients with early-onset and late-onset hyperammonemia, respectively, in a study in the United States.[11] In patients of severe hepatic encephalopathy, survival probability at 1 and 3 years of follow-up has been reported to be 42% and 23%, respectively.[28]

Complications

Elevated levels of ammonia, a potent neurotoxin, can result in life-threatening complications due to CNS damage, which includes cerebral edema, raised intracranial pressure, brain herniation, and coma. Osmotic demyelination syndrome is a potential complication of the treatment of hyperammonemia in patients with ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency.[29]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be educated regarding the signs and symptoms of hyperammonemia, which include lethargy, confusion, gait abnormalities, and vomiting. Education regarding medication compliance is vital. This is especially important for patients of cirrhosis. Diet plans should be provided individually to patients, and emphasis should be placed on important dietary restrictions at each visit. Information regarding specific dietary supplements should be provided. Patients should be informed that exercise is not completely restricted, and caloric intake should be increased to avoid protein breakdown in patients who wish to follow an active lifestyle. In children with urea cycle defects, growth and development should be monitored on each visit, and parents should be guided accordingly. Families with an infant diagnosed with urea cycle disorder should be informed of the availability of antenatal tests for diagnosis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Hyperammonemia is a metabolic abnormality that can occur in multiple disorders and can result in serious complications that need to be recognized and treated early. More than 90% of the patients develop hyperammonemia as a result of liver dysfunction, but various other diseases, that can lead to life-threatening complications fairly early in the disease course, need to be kept in mind. Health-care providers need to be well aware of the causes, pathophysiology, clinical signs and symptoms, and treatment strategies for managing hyperammonemia and the underlying defect contributing to the condition. An approach with effective interprofessional communication is required to ensure patient care. The interprofessional team includes internists, gastroenterologists, pediatricians, neonatologists, neurologists, general surgeons, urologists, hematologists, nurses, and pharmacists. Consultations with nephrologists for hemodialysis, dieticians, and geneticists for genetic counseling are needed in most cases. Emphasis should be placed on enhancing patient-centered care and safety, and all efforts should be targeted towards enhancing patient outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Upadhyay R, Bleck TP, Busl KM. Hyperammonemia: What Urea-lly Need to Know: Case Report of Severe Noncirrhotic Hyperammonemic Encephalopathy and Review of the Literature. Case reports in medicine. 2016:2016():8512721 [PubMed PMID: 27738433]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOlde Damink SW, Jalan R, Dejong CH. Interorgan ammonia trafficking in liver disease. Metabolic brain disease. 2009 Mar:24(1):169-81. doi: 10.1007/s11011-008-9122-5. Epub 2008 Dec 9 [PubMed PMID: 19067143]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBarmore W, Azad F, Stone WL. Physiology, Urea Cycle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020695]

Arranz JA, Riudor E, Marco-Marín C, Rubio V. Estimation of the total number of disease-causing mutations in ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) deficiency. Value of the OTC structure in predicting a mutation pathogenic potential. Journal of inherited metabolic disease. 2007 Apr:30(2):217-26 [PubMed PMID: 17334707]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYadav SK, Srivastava A, Srivastava A, Thomas MA, Agarwal J, Pandey CM, Lal R, Yachha SK, Saraswat VA, Gupta RK. Encephalopathy assessment in children with extra-hepatic portal vein obstruction with MR, psychometry and critical flicker frequency. Journal of hepatology. 2010 Mar:52(3):348-54. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.12.012. Epub 2010 Jan 6 [PubMed PMID: 20137823]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDe Jonghe B, Janier V, Abderrahim N, Hillion D, Lacherade JC, Outin H. Urinary tract infection and coma. Lancet (London, England). 2002 Sep 28:360(9338):996 [PubMed PMID: 12383670]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFelig DM, Brusilow SW, Boyer JL. Hyperammonemic coma due to parenteral nutrition in a woman with heterozygous ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Gastroenterology. 1995 Jul:109(1):282-4 [PubMed PMID: 7797025]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTrivedi M, Zafar S, Spalding MJ, Jonnalagadda S. Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency unmasked because of gastrointestinal bleeding. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2001 Apr:32(4):340-3 [PubMed PMID: 11276280]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShah S, Wang R, Vieux U. Valproate-induced hyperammonemic encephalopathy: a case report. Journal of medical case reports. 2020 Jan 25:14(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s13256-020-2343-x. Epub 2020 Jan 25 [PubMed PMID: 31980035]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCheung E, Wong V, Fung CW. Topiramate-valproate-induced hyperammonemic encephalopathy syndrome: case report. Journal of child neurology. 2005 Feb:20(2):157-60 [PubMed PMID: 15794187]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSummar ML, Dobbelaere D, Brusilow S, Lee B. Diagnosis, symptoms, frequency and mortality of 260 patients with urea cycle disorders from a 21-year, multicentre study of acute hyperammonaemic episodes. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992). 2008 Oct:97(10):1420-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00952.x. Epub 2008 Jul 17 [PubMed PMID: 18647279]

Llansola M, Rodrigo R, Monfort P, Montoliu C, Kosenko E, Cauli O, Piedrafita B, El Mlili N, Felipo V. NMDA receptors in hyperammonemia and hepatic encephalopathy. Metabolic brain disease. 2007 Dec:22(3-4):321-35 [PubMed PMID: 17701332]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSepehrinezhad A, Zarifkar A, Namvar G, Shahbazi A, Williams R. Astrocyte swelling in hepatic encephalopathy: molecular perspective of cytotoxic edema. Metabolic brain disease. 2020 Apr:35(4):559-578. doi: 10.1007/s11011-020-00549-8. Epub 2020 Mar 7 [PubMed PMID: 32146658]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVaquero J, Chung C, Cahill ME, Blei AT. Pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy in acute liver failure. Seminars in liver disease. 2003 Aug:23(3):259-69 [PubMed PMID: 14523679]

Clay AS, Hainline BE. Hyperammonemia in the ICU. Chest. 2007 Oct:132(4):1368-78 [PubMed PMID: 17934124]

Rosario M, McMahon K, Finelli PF. Diffusion-weighted imaging in acute hyperammonemic encephalopathy. The Neurohospitalist. 2013 Jul:3(3):125-30. doi: 10.1177/1941874412467806. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24167645]

U-King-Im JM, Yu E, Bartlett E, Soobrah R, Kucharczyk W. Acute hyperammonemic encephalopathy in adults: imaging findings. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2011 Feb:32(2):413-8. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2290. Epub 2010 Nov 18 [PubMed PMID: 21087942]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTakanashi J, Barkovich AJ, Cheng SF, Weisiger K, Zlatunich CO, Mudge C, Rosenthal P, Tuchman M, Packman S. Brain MR imaging in neonatal hyperammonemic encephalopathy resulting from proximal urea cycle disorders. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2003 Jun-Jul:24(6):1184-7 [PubMed PMID: 12812952]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAmes EG, Luckritz KE, Ahmad A. A retrospective review of outcomes in the treatment of hyperammonemia with renal replacement therapy due to inborn errors of metabolism. Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, Germany). 2020 Sep:35(9):1761-1769. doi: 10.1007/s00467-020-04533-3. Epub 2020 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 32232638]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAdam MP, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, Amemiya A, Camacho J, Rioseco-Camacho N. Hyperornithinemia-Hyperammonemia-Homocitrullinuria Syndrome. GeneReviews(®). 1993:(): [PubMed PMID: 22649802]

Arbeiter AK, Kranz B, Wingen AM, Bonzel KE, Dohna-Schwake C, Hanssler L, Neudorf U, Hoyer PF, Büscher R. Continuous venovenous haemodialysis (CVVHD) and continuous peritoneal dialysis (CPD) in the acute management of 21 children with inborn errors of metabolism. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2010 Apr:25(4):1257-65. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp595. Epub 2009 Nov 23 [PubMed PMID: 19934086]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAls-Nielsen B, Gluud LL, Gluud C. Nonabsorbable disaccharides for hepatic encephalopathy. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2004:(2):CD003044 [PubMed PMID: 15106187]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBass NM, Mullen KD, Sanyal A, Poordad F, Neff G, Leevy CB, Sigal S, Sheikh MY, Beavers K, Frederick T, Teperman L, Hillebrand D, Huang S, Merchant K, Shaw A, Bortey E, Forbes WP. Rifaximin treatment in hepatic encephalopathy. The New England journal of medicine. 2010 Mar 25:362(12):1071-81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907893. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20335583]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSaraswat VA, Saksena S, Nath K, Mandal P, Singh J, Thomas MA, Rathore RS, Gupta RK. Evaluation of mannitol effect in patients with acute hepatic failure and acute-on-chronic liver failure using conventional MRI, diffusion tensor imaging and in-vivo proton MR spectroscopy. World journal of gastroenterology. 2008 Jul 14:14(26):4168-78 [PubMed PMID: 18636662]

Liotta EM, Lizza BD, Romanova AL, Guth JC, Berman MD, Carroll TJ, Francis B, Ganger D, Ladner DP, Maas MB, Naidech AM. 23.4% Saline Decreases Brain Tissue Volume in Severe Hepatic Encephalopathy as Assessed by a Quantitative CT Marker. Critical care medicine. 2016 Jan:44(1):171-9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001276. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26308431]

Mohsenin V. Assessment and management of cerebral edema and intracranial hypertension in acute liver failure. Journal of critical care. 2013 Oct:28(5):783-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.04.002. Epub 2013 May 15 [PubMed PMID: 23683564]

Jiang Q, Jiang XH, Zheng MH, Chen YP. L-Ornithine-l-aspartate in the management of hepatic encephalopathy: a meta-analysis. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2009 Jan:24(1):9-14. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05582.x. Epub 2008 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 18823442]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBustamante J, Rimola A, Ventura PJ, Navasa M, Cirera I, Reggiardo V, Rodés J. Prognostic significance of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis. Journal of hepatology. 1999 May:30(5):890-5 [PubMed PMID: 10365817]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCardenas JF, Bodensteiner JB. Osmotic demyelination syndrome as a consequence of treating hyperammonemia in a patient with ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Journal of child neurology. 2009 Jul:24(7):884-6. doi: 10.1177/0883073808331349. Epub 2009 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 19225137]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence