Introduction

Interstitial lung disease (ILD), sometimes called diffused parenchymal diseases, describes a heterogeneous collection of distinctive lung disorders classified on the grounds of shared clinical, radiographic, physiologic or pathologic factors. What makes it difficult to understand this group of diseases is the confusing terminology. The pathogenetic sequence in actuality involves a series of inflammation and fibrosis that extends beyond disrupting the interstitial bed (as the name implies) to changing the parenchyma (alveoli, alveolar ducts, and bronchioles). The list of causes of infiltrative diseases is never-ending. Many are extremely rare. The pattern of disease spread varies among the groups; for that reason establishing the correct diagnosis is vital.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The classification system used to describe interstitial lung disease categorizes conditions based on clinical, histopathological or radiologic parameters.[1] Clinical classification groups ILD by its causes to help differentiate exogenous or endogenous factors.[2] Interstitial lung disease diseases without identifiable causes get grouped under idiopathic/primary which uses the histopathological and radiological approach as its infrastructure.

Known causes.

- Environmental and occupational exposure

Long-term exposure to occupational or environmental agents can have a toxic effect on the lungs. Common agents are mineral dust, organic dust, and toxic gases.[3] Many different types of mineral dust have correlations, but the ones frequently cited with the disease are silica, asbestos, coal mine dust, beryllium, and hard metal. Organic dust includes mold spores and aerosolized bird droppings. Inhaled toxic gases (methane, cyanide) affect the airways either by direct injury or through reactive oxygen molecules. Epidemiologically, the magnitude of exposure-related injuries is hard to measure. It probably occurs even more commonly than estimated. That is why it is invaluable to thoroughly review a patient’s entire employment history and home to look for any evidence of potential agent-disease relationships.[3]

- Auto-Immune diseases

Connective tissue diseases and vasculitides affect all areas of the lungs (bronchioles, parenchyma, alveoles) which is why interstitial lung disease is a common feature of rheumatology diseases.[4][5]

- Drug-induced ILD: More than 350 drugs have been identified to cause pulmonary complications whether through reactive metabolites or as a component of a general response.[6][7] A diagnosis is possible with appropriate clinical findings and in most cases should be established after excluding other causes. Radiological findings may be unpredictable, but because drug reactions usually affect the parenchyma, an interstitial pattern is what is most observed. The histopathology is also variable. The common patterns seen are eosinophilic pneumonia or hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

- Idiopathic disease

This variant is the most common type. This main category is called idiopathic interstitial pneumonia which is a combination of inflammation and fibrosis as opposed to infectious pneumonia.[8] There are seven distinct types, differentiated by histopathological features with clear clinical distinctions. Most cases are sporadic, but genetics can play a role.

Epidemiology

Interstitial lung disease incidence rates in the United States have been difficult to determine. Many speculate that the prevalence is far more substantial than formerly described. The reason that the reported prevalence may be so low is because of failure to recognize the disease. ILD is a diagnosis of exclusion that requires extensive investigation.[9] Now, newer guidelines/classification have made it easier. The estimated incidence is 30 per 100000 per year. The overall prevalence is 80.9 per 100000 per year in males and 67.2 per 100000 per year in females.[10] These statistics derived from one of the most important epidemiologic studies, undertaken in Bernalillo County in New Mexico.

Pathophysiology

Many of the subsets of the disease are of unknown etiology. Regardless, they all ultimately share the same manner of development. The morphological changes seen histologically result from a sequence of inflammation within the parenchyma, which is the portion of the lung involved in gas exchange (the alveoli, the alveolar ducts, and the bronchioles). This compartment is the habitat to various proteins and pro-fibrotic elements. These proteins, after repeated cycles of activation, give rise to accumulation of connective tissue.[11] The trigger can be a known agent that deposited within the lung tissues. In some cases, the fibrosis arises spontaneously.

History and Physical

The most frequently reported symptom is a gradual onset of dyspnea, but sometimes it may simply be a cough. For example, in patients with bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia, an unrelenting cough is usually the presenting symptom.[12] Pleuritic chest pain is uncommon overall but does occur in some subtypes such as sarcoidosis. Hemoptysis may present from diffuse alveolar hemorrhages. On the other hand, a patient can be completely asymptomatic but have abnormal imaging.

The history should include details regarding potential environmental or occupational exposures, current and past medications lists, history of any radiation exposures, fumes, dust, toxic inhalation. Family history is essential as genetics can play a role. Symptoms of rheumatologic diseases should be considered, but always keep in mind that dyspnea may be the only presenting symptom for rheumatological-associated interstitial lung disease.

On physical exam, bibasilar crackles are characteristics but not necessarily a consistent finding. Patients with advanced disease may have digital clubbing or physical signs of pulmonary hypertension such as increased intensity of P2 of the second heart sound.

Evaluation

Determining the cause and severity of interstitial lung disease can be difficult. A clinician may be able to reach a diagnosis with a detailed history and supporting laboratory but might need to involve an interprofessional team for a higher diagnostic yield.[13] Interstitial lung disease deals with a diversified collection of disorders with different management approach and prognosis, which is why arriving at a final diagnosis, is paramount. It starts with a detailed patient history and physical exam coupled with laboratory testing, imaging, physiologic testing and possibly a biopsy.

Initial routine laboratory evaluation consists of complete blood count to check for evidence of hemolytic anemia for example, as can be seen in SLE, or eosinophilia, as can be seen in drug-induced. Laboratory testing should also include hepatic function, renal function, and serologic studies. In some cases may, infectious studies may be appropriate (HIV, hepatitis).

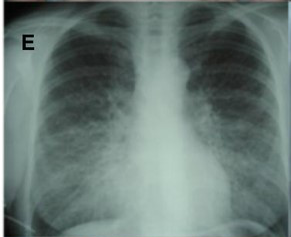

Imaging workup starts with a routine chest radiograph. The most common radiographic feature observed is a reticular pattern, however nodular or mixed patterns can be seen.[14] Occasionally some of these patterns can help you narrow down the possibilities. The presence of mediastinal lymphadenopathy on an XRay might signify the presence of lymphoma or sarcoidosis. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) can offer a better characterization of the disease and even aid in diagnosis in case of a negative CXR; the HRCT needs to be done in a supine position.

In some cases, it may show a classic radiological pattern of some disease like usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP). The classic radiological pattern of UIP on HRCT is subpleural and basilar predominant changes, reticular patterns, honeycomb changes with or without traction bronchiectasis. If the diagnosis remains unclear after combining history, laboratory results and radiological findings, invasive workup may be helpful. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) gives nonspecific results, meaning there are no findings in a BAL that is proven pathognomonic for a particular type of ILD. BAL, however, can be helpful when it comes to narrowing down the options. For example, in patients suspected of hypersensitivity pneumonitis, BAL will show marked lymphocytosis. The decision to pursue a lung biopsy should be individualized. Not all cases require a lung biopsy. It is most helpful in diagnosing sarcoidosis and idiopathic interstitial pneumonia.

Complete lung functions and oxymetry are necessary for all patients with ILD for prognostication and monitoring of the disease.

Treatment / Management

For those interstitial lung disorders with known causes, avoidance of irritant is essential. General supportive measures will include smoking cessation, pulmonary rehabilitation which can help improve functionality, and good pulmonary hygiene. Supplemental oxygen is necessary for those who demonstrate hypoxemia (SaO2 less than 88). With progressive disease despite the elimination of offending agent, corticosteroids are desirable. Patients with bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP) or hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) have rapid, dramatic improvement with corticosteroids. For cases that do not respond to corticosteroids, immunosuppressant therapy is an investigational therapy.

The mainstay therapy for treatment of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia is corticosteroids and immunosuppressive therapies to intercept the inflammatory process within the lungs.[15] Right now, nintedanib and pirfenidone are immunosuppressant drugs that have been approved but only in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.[16] Some studies have provided indirect evidence that early therapy within the course of the disease might correlate with therapeutic responsiveness because the lung architecture has not suffered significant derangement. Once fibrosis initiates, there has not been any treatment to reverse that process, but nintedanib can slow disease progression.[13] Transplant is the sole treatment modality that can reinstate physiological function in patients.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential includes pulmonary edema, ARDS, bacterial, fungal or viral pneumonia.

Prognosis

Prognosis varies amongst the subgroups of interstitial lung diseases.[17] Typical treatment responsive sub-classes are the following: acute eosinophilic pneumonia, cellular interstitial pneumonia, BOOP, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis, pulmonary capillaritis, granulomatous interstitial pneumonitis and finally, alveolar proteinosis. But in any case, prognosis still correlates with the extent of the disease on presentation. The subclasses that are notoriously resistant to therapy are advanced conditions such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Complications

Complications include worsening hypoxia, cardiovascular diseases, pulmonary HTN, infections.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of interstitial lung disease are complex and requires an interprofessional team that includes the primary physician, nurse practitioner, pulmonologist, thoracic surgeon, pathologist, and radiologist. Once the diagnosis is made, asymptomatic patients may be placed under observation, but all symptomatic patients need treatment. The condition is known to progress to fibrosis and end-stage lung disease, hence long term monitoring is essential. Educating patients about the importance of smoking cessation is critical. The quality of life of most patients is poor, marked by significant respiratory distress with minimal physical activity.[16][18]

Interstitial lung disease is best addressed by an interprofessional team that includes the patient's primary care doctor, a pulmonologist, nursing staff, and pharmacists, as well as pulmonary function techs and respiratory therapists, to provide optimal patient diagnosis and care. [Level V]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Rivera-Ortega P, Molina-Molina M. Interstitial Lung Diseases in Developing Countries. Annals of global health. 2019 Jan 22:85(1):. pii: 4. doi: 10.5334/aogh.2414. Epub 2019 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 30741505]

Mikolasch TA, Garthwaite HS, Porter JC. Update in diagnosis and management of interstitial lung disease . Clinical medicine (London, England). 2017 Apr:17(2):146-153. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.17-2-146. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28365626]

Luckhardt TR, Müller-Quernheim J, Thannickal VJ. Update in diffuse parenchymal lung disease 2011. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2012 Jul 1:186(1):24-9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0509UP. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22753686]

Mira-Avendano I, Abril A, Burger CD, Dellaripa PF, Fischer A, Gotway MB, Lee AS, Lee JS, Matteson EL, Yi ES, Ryu JH. Interstitial Lung Disease and Other Pulmonary Manifestations in Connective Tissue Diseases. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2019 Feb:94(2):309-325. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.09.002. Epub 2018 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 30558827]

Kalchiem-Dekel O, Galvin JR, Burke AP, Atamas SP, Todd NW. Interstitial Lung Disease and Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Practical Approach for General Medicine Physicians with Focus on the Medical History. Journal of clinical medicine. 2018 Nov 24:7(12):. doi: 10.3390/jcm7120476. Epub 2018 Nov 24 [PubMed PMID: 30477216]

Schwaiblmair M, Behr W, Haeckel T, Märkl B, Foerg W, Berghaus T. Drug induced interstitial lung disease. The open respiratory medicine journal. 2012:6():63-74. doi: 10.2174/1874306401206010063. Epub 2012 Jul 27 [PubMed PMID: 22896776]

Skeoch S, Weatherley N, Swift AJ, Oldroyd A, Johns C, Hayton C, Giollo A, Wild JM, Waterton JC, Buch M, Linton K, Bruce IN, Leonard C, Bianchi S, Chaudhuri N. Drug-Induced Interstitial Lung Disease: A Systematic Review. Journal of clinical medicine. 2018 Oct 15:7(10):. doi: 10.3390/jcm7100356. Epub 2018 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 30326612]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCapron F. [New classification of interstitial lung disease]. Revue de pneumologie clinique. 2005 Jun:61(3):133-40 [PubMed PMID: 16142185]

Raghu G, Nyberg F, Morgan G. The epidemiology of interstitial lung disease and its association with lung cancer. British journal of cancer. 2004 Aug:91 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S3-10 [PubMed PMID: 15340372]

Coultas DB, Zumwalt RE, Black WC, Sobonya RE. The epidemiology of interstitial lung diseases. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1994 Oct:150(4):967-72 [PubMed PMID: 7921471]

Suki B, Stamenović D, Hubmayr R. Lung parenchymal mechanics. Comprehensive Physiology. 2011 Jul:1(3):1317-51. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c100033. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23733644]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRyu JH, Olson EJ, Midthun DE, Swensen SJ. Diagnostic approach to the patient with diffuse lung disease. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2002 Nov:77(11):1221-7; quiz 1227 [PubMed PMID: 12440558]

Jakubczyc A, Neurohr C. [Diagnosis and Treatment of Interstitial Lung Diseases]. Deutsche medizinische Wochenschrift (1946). 2018 Dec:143(24):1774-1777. doi: 10.1055/a-0622-9299. Epub 2018 Dec 3 [PubMed PMID: 30508858]

Raghu G, Brown KK. Interstitial lung disease: clinical evaluation and keys to an accurate diagnosis. Clinics in chest medicine. 2004 Sep:25(3):409-19, v [PubMed PMID: 15331183]

Kondoh Y, Taniguchi H, Yokoi T, Nishiyama O, Ohishi T, Kato T, Suzuki K, Suzuki R. Cyclophosphamide and low-dose prednisolone in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and fibrosing nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. The European respiratory journal. 2005 Mar:25(3):528-33 [PubMed PMID: 15738299]

Cottin V, Wollin L, Fischer A, Quaresma M, Stowasser S, Harari S. Fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: knowns and unknowns. European respiratory review : an official journal of the European Respiratory Society. 2019 Mar 31:28(151):. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0100-2018. Epub 2019 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 30814139]

Kolb M, Vašáková M. The natural history of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Respiratory research. 2019 Mar 14:20(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s12931-019-1022-1. Epub 2019 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 30871560]

Sciriha A, Lungaro-Mifsud S, Fsadni P, Scerri J, Montefort S. Pulmonary Rehabilitation in patients with Interstitial Lung Disease: The effects of a 12-week programme. Respiratory medicine. 2019 Jan:146():49-56. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2018.11.007. Epub 2018 Nov 23 [PubMed PMID: 30665518]