Introduction

An intracardiac abscess carries a high level of morbidity and mortality. The location of the abscess can be within the myocardium, endocardium, or valves (native, prosthetic, or mechanical). Infective endocarditis is an infection of the heart valves, which, if not promptly treated, can progress to a cardiac abscess in 20% to 30% of cases.[1]

An abscess anywhere in the myocardium can present as an interventricular abscess in rare cases. The interventricular septum is a thick, muscular wall that separates the ventricles. However, the proximal portion of the septum is thin and membranous, and the distal part is thick and muscular. The proximity of interventricular septum to the valves makes it highly vulnerable to developing an abscess.[2][3] An interventricular abscess usually occurs as an extension of infective endocarditis from cardiac valves, most commonly aortic valve endocarditis. [4] Due to the progression of endocarditis into a paravalvular abscess, it can present as conduction blocks, and/or congestive heart failure. Even with optimal treatment, the inpatient mortality of aortic valve endocarditis has been reported as high as 40% to 79%, depending on patient age, comorbidity, and the type of organism.[5]

There are several risk factors for developing infective endocarditis. These include rheumatic, congenital, and degenerative valve lesions, intracardiac prosthetic devices, intravenous drug use, and use of access devices (e.g., indwelling catheters, hemodialysis, pacemakers, etc.).[6] Staphylococcus aureus is the most common cause of infective endocarditis. Data from greater than 70 million hospitalizations in the United States from 1999 to 2008 suggest an increase in the incidence of Staphylococcus aureus rate of infection relative to other microorganisms. In another study on endocarditis, Staphylococci were implicated in 57.5% of all cases, followed by streptococci and enterococci at 33.3%.[7] Bacterial presence leads to colonization and systemic infection as a consequence of intravascular catheters, surgical wounds, prosthetic devices, hemodialysis, etc.[8][9]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

An interventricular septal abscess most commonly arises from the progression of infective endocarditis in a native or prosthetic valve to the interventricular septum. A perivalvular abscess due to infective endocarditis can also extend and become an interventricular abscess.[10]

The primary etiology of the interventricular septal abscess is disseminated bacteremia, an extension of infective source or local infection.[11][12] The factors leading to an interventricular abscess are similar to infective endocarditis, including degenerative valves, mechanical valves, prosthetic valves, and intravenous illicit drug use. Other predisposing factors known to lead to the formation of the abscess in the literature are:

- Trauma

- Deep penetrating wounds of the cardiac tissue

- Infected coronary stents

- Infected sternal incisions

- Infected transplanted hearts

- Deep burns

- Immunocompromised patients

- HIV

- Parasitic infections

- Pseudoaneurysms

- Suppurative pericarditis

Epidemiology

An interventricular abscess is a rare complication of infective endocarditis. It is more prevalent in developing countries where patients may not have access to antibiotics for simple bacteremic infections that seed the cardiac structures and later lead to infective endocarditis. In the U.S. and Europe, patients often have predisposing medical conditions or devices that increase the chance of developing an infection. Among microbiological etiologies, Staphylococci are the leading cause of infective endocarditis, producing a septal abscess. The incidence of infective endocarditis between 2000 and 2011 in the United States increased from 11 per 100,000 to 15 per 100,000 individuals.[13] It is challenging to state a precise incidence of interventricular abscess because the criteria for diagnosing infective endocarditis continue to evolve. The variability of risk factors, predisposing medical conditions, microbiological agents, valvular pathologies, the use of intravenous illicit drug use, and socioeconomic factors are also possible causes of an increasing incidence of the interventricular abscess with infective endocarditis.

The most common infectious organisms causing interventricular abscess include:

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Haemophilus species

- Enterococci

- Escherichia coli

- Beta-hemolytic streptococci

- Streptococcus pneumoniae

- Bacteroides species

- Parasitic organisms

- Hydatid cysts

- Listeria monocytogenes

- HIV

- Immunocompromised states

- Miscellaneous

Pathophysiology

The damaged cardiac endothelium in the diseased valve harbors the nidus for bacterial colonization either by direct trauma or inflammation. The exposed subendothelial tissue accounts for the production of extracellular matrix proteins and tissue factor along with the deposition of fibrin and platelets. It leads to the formation of sterile vegetations that become colonized by bacteria, thus resulting in infective endocarditis.[6] Staphylococcus aureus, with the help of its cell-wall adherence proteins, attaches to the extracellular matrix proteins, fibrin, and platelets. This series of events culminates in the subsequent invasion of the endothelial cell and ongoing inflammation.[14] Other organisms associated with infective endocarditis (streptococci, enterococci, Candida species, and pseudomonas) produce biofilms that embed in the extracellular matrix with cell-to-cell communications and gene expression leading to their proliferation. These biofilms serve to protect the bacteria from the host immune response and prevent the entry of antimicrobial agents inside the bacteria.[15] Complicated infective endocarditis can spread to the surrounding tissues leading to the formation of an interventricular septal abscess.

Histopathology

The biopsy and histological assessments are usually not done for the diagnostic workup of the septal abscesses. However, gross and microscopic findings can be obtained from surgically removed diseased valves or tissue obtained during an autopsy. In the setting of native or prosthetic valves, infective endocarditis can lead to a myocardial abscess. It is caused by the spread of infection beyond the extent of the valve ring into the annulus, peri-annular tissue, chordae tendinae, and the fibrous tissue surrounding the mitral and aortic valves. Invasion into the ring and septum can lead to the dehiscence of the prosthetic valve and hemodynamically significant paravalvular regurgitation. Histological inspection of a myocardial abscess will often show a polymorphonuclear predominance with damaged cardiac tissue and collagen degradation.[16]

History and Physical

The history and the physical examination findings of the interventricular abscess will vary depending on the acuity of presentation, the extent of involvement of the myocardium, damage to the conduction pathways, and patency of the cardiac valves. There should be a high index of suspicion for an interventricular abscess in patients with arrhythmias, heart block, and extension of the abscess into the annulus.[16]

HISTORY: In the setting of an acute infection, a classical presentation of acute hemodynamic distress is more likely.[17][16][18] The history should revolve around the area affected by an interventricular abscess, risk factors, degree of conduction block, and degree of contraction/anatomical abnormality. An interventricular abscess can present with the following symptoms in history:

- Dizziness

- Dyspnea

- Chest pain likely myocardial infarction, or angina symptoms

- Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea

- Cyanosis

- Orthopnea

- Syncope or near syncope

- Joint pain

- Cough

- Skin rashes

- Recent surgery or trauma to the heart

- Travel to endemic areas

- Exposure to an animal

- Exposure to infection risk factor

PHYSICAL EXAM: The signs and symptoms of an interventricular septal abscess may reflect the presence of infective endocarditis.[17][16][18] The clinical features can persist depending on the antibiotic response on bacteria. No pertinent physical examination can mark the diagnosis of an interventricular abscess, but helpful examination findings include:

- Bradycardia

- Heart failure signs and symptoms including S3, inspiratory basal crackles in lungs, jugular venous distention, and bilateral leg edema, abdominal ascites

- Aortic regurgitation (AR) or dilated aortic root findings including decrescendo murmur (AR), soft mid-diastolic rumble heard at the apical area (Austin Flint murmur), Corrigan's pulse, De Musset's sign, Quincke's sign, Muller's sign, Hill's sign, and Duroziez's sign.

- A ventricular septal defect may present as a systolic murmur at the left lower sternal border, cyanosis, and heart failure.

- Pulmonary hypertension signs that include a loud P2 component of the second heart sound.

- Mitral regurgitation findings that include a holosystolic murmur at the apex, and pulmonary edema.

- Diffuse multiorgan involvement feature due to systemic emboli from an abscess.

- Back tenderness due to osteomyelitis

- Petechia

- Sublingual or splinter hemorrhages

- Osler nodes

- Janeway lesions

- Roth spots

- Splenomegaly

Evaluation

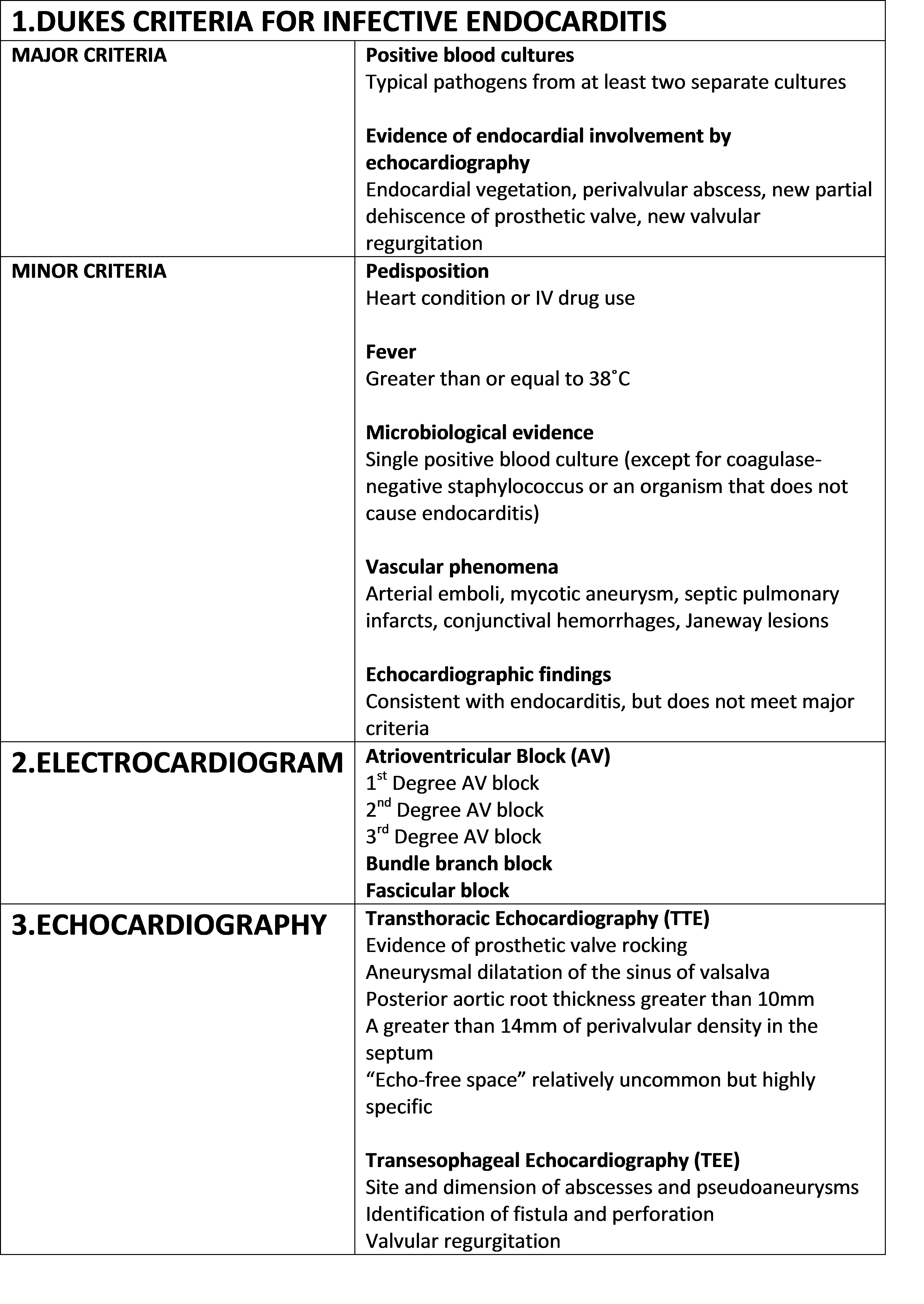

The Duke's criteria were initially proposed in 1994 to help establish the diagnosis of infective endocarditis.[19] The determination of infective endocarditis is important in the establishment of the diagnosis of an interventricular septal abscess. It is a set of clinical criteria comprising of major and minor criteria. It requires two major and one minor, one major and three minor or five minor criteria for the diagnosis. The diagnosis of infective endocarditis appears in table 1.

A simplified version of the diagnosis of the interventricular abscess includes the diagnosis of infective endocarditis, conduction block, and imaging showing visible interventricular abscess.[16] Furthermore, diagnostic evaluation of the interventricular abscess includes routine blood work, inflammatory testing, electrocardiogram, and imaging for both infective endocarditis and interventricular abscess.[20]

Routine Blood Tests: In acute cases, regular blood work includes a complete blood profile, which may reveal an elevated white blood cell count with a left shift, normocytic anemia, and thrombocytopenia. In the subacute case, white blood cell count can be normal.[20]

Infectious/ inflammatory tests: Tests such as acute phase reactants and inflammatory markers can aid in the diagnosis of infective endocarditis and interventricular abscess. These tests include erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), ferritin, and other inflammatory markers. An absence of elevated ESR and CRP holds the significance of ruling out an active acute or chronic infection.[20]

Blood Cultures: Three blood cultures from different sites are a cornerstone of the diagnosis of infective endocarditis and interventricular abscess. Three blood cultures can detect up to 98% of bacteremia.[20] Although valve culture can be useful for cases that meet the Duke's criteria, many patients have negative blood cultures.[21] Valvular cultures should be avoided if a patient does not meet Duke's criteria, as it can lead to false-positive findings. In a study by Munoz et al., 1030 valves were cultured after surgical removal of valves in infective endocarditis; the results showed a positive valvular culture in 39% of cases that met Duke's criteria and 28% positive culture rate without meeting Duke's criteria.[21]

Urinalysis: Urine workup may show proteinuria and microscopic hematuria. Urine findings can be due to immune complex deposits due to infection, or due to septic emboli to the kidney from an interventricular abscess or infective endocarditis.[20]

Electrocardiogram: This is a beneficial test for the interventricular abscess. EKG may show a variety of conduction blocks.[22] The conduction blocks can present as first-degree atrioventricular block, second-degree atrioventricular block, third-degree atrioventricular block, or bundle branch and fascicular blocks.[17][23][24] The development of heart block in infective endocarditis is a good indicator of an extension of infective endocarditis to the myocardial/interventricular septum.[25] The appearance of a new AV block on EKG has a positive predictive value of 88% but a low sensitivity of 45% for abscess formation.[26]

Imaging: Echocardiography is the primary imaging modality for infective endocarditis and interventricular abscess. Other helpful imaging studies may include cardiac computed tomography (cardiac CT), magnetic Resonance Imaging, scintigraphy, and angiography.

Echocardiography: Transthoracic echocardiography and transesophageal echocardiography aid in the early diagnosis of the interventricular abscess and infective endocarditis. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is the first echocardiography imaging to use for diagnosis and guide management. TTE has a low sensitivity of 23% and a very high specificity of 98.6% for diagnosing the myocardial abscess. According to a study by Ellis et al., the specific criteria of echocardiography for detection of the myocardial abscess include the following:[27]

-

Evidence of the prosthetic valve rocking

- Aneurysmal dilatation of the Valsalva sinus

-

Posterior aortic root thickness exceeding 10 mm

-

A higher than 14 mm of perivalvular density in the septum

- A relatively uncommon but highly specific finding of "echo-free space."

M-mode echocardiography and two-dimensional (2D) echocardiography can play a significant role in the diagnosis of a ventricular septal abscess.[4] Real-time 3D transthoracic echocardiography, as compared to 2-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography, is more applicable in confirming the diagnosis of a myocardial abscess. It also delineates its boundaries and helps in identifying extension into adjacent structures.[28]

Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) holds a high sensitivity for the detection of the myocardial /interventricular abscess than TTE.[29] In a study by Daniel et al., 43 patients had a documented perivalvular abscess at surgery or autopsy with a TTE sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values (NPV) of 87, 95, 91, and 92 percent respectively.[30]

Computed Tomography: It has a low sensitivity as compared to other imaging modalities.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging: MRI is an excellent imaging modality in providing functional, morphologic, and prognostic value in a single examination.[31] But as compared to echocardiography, it has proven to be less portable and has a limited resolution.

Scintigraphy: Those areas where transthoracic echocardiography use is limited to assess the visualization of the myocardial abscess, indium-111 leukocyte scintigraphy is employed. It is used mainly in cases of prosthetic valve endocarditis and may allow identification of myocardial abscess formation earlier than other imaging modalities.[32] The technique involves the use of a few milliliters of venous blood mixed with an anticoagulant solution. After centrifugation, the white blood cells are separated and labeled with a radioactive isotope; the cells are resuspended in isotonic sodium chloride solution and reinjected into the patient. Then with the help of a gamma-ray camera, images are obtained within 16 to 24 hours. The viable radioactive leukocytes accumulate in the areas of inflammation or abscess. If transesophageal echocardiography is available, indium-111 scintigraphy is seldom needed.

Treatment / Management

The goal of the management is to identify and treat the root cause of infection, lower risk factors, eradicate infection by medical therapy, and surgery, which is often necessary. Management decisions will depend on the presence of complications of interventricular abscess or infective endocarditis, including hemodynamic instability, conduction block, and heart failure.[33] Initial management includes stabilizing vital signs with IV fluids if needed, pacing to manage heart block, and treating the heart failure with the usual cocktail of medications. An infectious disease specialist will also help select an appropriate antibiotic regimen and help in the follow-up. Treatment may last as long as two to six months and may require multiple rounds of oral or intravenous antibiotics. Initially, empirical antimicrobial therapy is administered until the results of blood cultures are available. Then the antibiotic treatment will undergo revision according to the defined pathogen and susceptibility. Staphylococcus aureus is the presumed primary causative pathogen, and it most frequently warrants coverage by combination antimicrobial therapy.[33][34] The administration of a combination of an aminoglycoside with vancomycin or penicillin is the standard approach. This regimen has demonstrated in vitro bactericidal activity against Staphylococcus aureus.[35] The unique characteristics of this infection can pose serious challenges. The antibiotics may fail to eradicate the disease; therefore, at least 6 to 8 weeks of prolonged parenteral, bactericidal therapy is necessary.[35][33](B2)

Open surgical incision and drainage or needle drainage is often a component of the management of the interventricular abscess.[36] In the presence of a severe complication such as a ruptured interventricular abscess, causing a ventricular septal defect, surgery is often required.[36][16] Open-heart surgery may involve aortic root replacement and abscess evacuation. The timing of surgical intervention depends on patient stability and response to antibiotics.(B3)

Differential Diagnosis

The interventricular septal abscess is a rare and uncommon complication of infective endocarditis.[16] It generally presents with vague signs and symptoms and can mimic many other medical disorders which include:

- Acute rheumatic fever

- Congenital septal hypertrophy

- Septal cardiac tumor

- Aortic or mitral regurgitation

- Ventricular septal defect

- Atrioventricular or bundle branch block

- Acute myocardial infarction

- Myocardial rupture

- Cardiac tumor

- Congestive heart failure

Prognosis

The morbidity and mortality rates of patients with complicated infective endocarditis are high. The severity of the disease varies according to the origin of infection and preexisting comorbidities. The biomarkers of acute infection and indicators of the severity of the illness (scores and multiple organ failure) are independent risk factors for mortality. Surgical intervention for abscesses is an independent predictor at 30 days of poorer outcomes.[37] Although patients who require surgical management have a high mortality rate, patients who do recover often will an excellent long-term outcome with a low rate of reinfection.[38] In young and otherwise healthy individuals, the prognosis is generally favorable. Other significant prognostic factors affecting the mortality rate include Charlson score of less than 3, the diagnosis of endocarditis before ICU admission, the use of aminoglycosides, and septic pulmonary embolism.[39]

Complications

The interventricular septal abscess is associated with severe morbidity and mortality. Following complications can occur in a patient during the disease course[16]:

- Myocardial wall perforation

- New-onset congestive heart failure

- The onset of new murmurs

- New-onset valvular regurgitation

- Poor response to antibiotics

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- Multiorgan failure

- Stroke

- Development of conduction defects or progression to bundle-branch block and atrioventricular block

- Miscellaneous (severe recurrent ventricular arrhythmias, pericarditis, etc.)

- Significant rapid clinical deterioration leading to death

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

A successful treatment outcome depends on the patient's initial underlying health, prompt diagnosis and treatment, and rehabilitation care. Medical treatment for these patients often requires 6 to 8 weeks of parenteral antibiotic therapy with close monitoring of hemodynamics. Serial echos need to be done to ensure that healing is occurring. The patient must be on a cardiac monitor to detect the presence of an arrhythmia or heart block. Even after surgery, complications are common, and close follow up is required. A patient who has had surgical intervention is still susceptible to develop postoperative complications, including pneumonia, urinary tract infection, and deep vein thrombosis. Adequate nutrition, attention to deep venous thrombosis, and stress ulcer prophylaxis are essential. Physiotherapy to prevent muscle atrophy, and an individualized rehabilitation plan for each patient potentially impacts both morbidity and mortality.

Consultations

The management of interventricular abscess requires an interprofessional team of consultants, including general medicine, cardiologist, cardiac surgeon, intensive care, pulmonologist, pathologist, infectious disease specialist, and cardiac rehabilitation.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Awareness and education about the prevention of infective endocarditis are pivotal in decreasing its incidence in the general population. The NICE guidelines for the prevention of infective endocarditis recommend such an approach. These guidelines recommend identifying patients with cardiac risk factors and providing additional education to patients about prevention, putting emphasis on maintaining good oral hygiene, outlining the benefits and risks associated with the antibiotic prophylaxis for procedures, and understanding when to seek medical advice. Also, additional information explaining the infectious risks of skin piercing or tattooing for patients already at elevated risk for infective endocarditis.[40]

Pearls and Other Issues

The prevention of infective endocarditis and interventricular septal abscess poses various challenges in the healthcare setting, due to its heterogeneous etiology, clinical features, and course of the disease.[41] The differing steps for its diagnosis and management are due to the lack of high-quality randomized control studies. As infective endocarditis is the most common reason for developing an interventricular septal abscess, it is possible to argue that efforts directed at prevention will have a much more significant impact.

Thomas Horder, in 1909, recognized the mouth as a significant source of bacteremia.[42] Dental procedures are the leading cause of infective endocarditis due to a high frequency of bacteremia produced by various oral procedures such as deep cleaning and tooth extraction. At present, the emphasis has shifted from antibiotic prophylaxis before dental procedures to better maintenance of oral hygiene. Toothbrushing has also been studied as a source of bacteremia, leading to the revision of prophylaxis guidelines in the United States and Europe. The use of antibiotic prophylaxis has been restricted to high-risk patients and increased the focus on educating the general population about proper oral hygiene.[43]

The risks associated with prolonged parenteral antibiotic therapy include nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity, and vestibular effects. A team of clinicians dedicated to the management of infective endocarditis team can play a vital role in monitoring and managing the complications. Unfortunately, such services are not readily available everywhere.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Interventricular septal abscess secondary to infective endocarditis remains a major clinical challenge — the involvement of an interprofessional team-based approach is essential to reducing the morbidity and mortality. Presenting patients also tend to have multiple co-morbidities, including depression, hepatitis C, and HIV infections. A structured approach for early diagnosis and treatment is needed. Contemporary management involving both pharmacologic and non-pharmacological therapy for mental illness is imperative.[44]

The interprofessional health-care team involved in its management includes physicians and health-care professionals from various fields working in harmony for better patient outcomes. A cardiologist needs to have a major role in aiding diagnosis and initiating treatment along with monitoring for associated complications like heart block, congestive heart failure, stroke, etc. A cardiothoracic surgeon is almost always involved in deciding the appropriate timing and necessity of surgery. Other physician involvements include an infectious disease specialist for ensuring appropriate antibiotics, an intensivist and pulmonologist for monitoring critically ill patients and nephrologists for managing renal dysfunction. The pathologist or laboratory technician has a role in determining the type of organism present in the blood cultures. The nursing responsibility centers on monitoring bodily functions and providing education to the patient and family; the nurses will be administering the IV antibiotics and monitoring for adverse reactions and therapeutic effectiveness; a cardiovascular specialty nurse is even better equipped to follow up these patients, and report any concerns promptly to the treating physician. Prompt pharmaceutical monitoring of drugs being administered by a cardiac or infectious disease specialty pharmacist to fine-tune antimicrobial therapy, adjust dosing, and prevent adverse reactions is necessary; this is especially true with kinetic dosing of aminoglycosides and vancomycin.

A dietician, physical therapist, and psychiatrist working in an integrated manner for the rehabilitation of these patients has proved to be beneficial in the perioperative period and keeping the team informed regarding progress or lack thereof.[45] All these disciplines coordinating as an interprofessional team are necessary for early diagnosis and treatment of interventricular septum abscesses and improve patient outcomes. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Toyoda N, Chikwe J, Itagaki S, Gelijns AC, Adams DH, Egorova NN. Trends in Infective Endocarditis in California and New York State, 1998-2013. JAMA. 2017 Apr 25:317(16):1652-1660. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.4287. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28444279]

Becher H, Hanrath P, Bleifeld W, Bleese N. Correlation of echocardiographic and surgical findings in acute bacterial endocarditis. European heart journal. 1984 Oct:5 Suppl C():67-70 [PubMed PMID: 6519089]

Arnett EN, Roberts WC. Prosthetic valve endocarditis: clinicopathologic analysis of 22 necropsy patients with comparison observations in 74 necropsy patients with active infective endocarditis involving natural left-sided cardiac valves. The American journal of cardiology. 1976 Sep:38(3):281-92 [PubMed PMID: 989258]

Incarvito J, Yang SS, Papa L, Fernandez J, Chang KS. Fungal endocarditis complicated by mycotic aneurysm of sinus of Valsalva, interventricular septal abscess, and infectious pericarditis: unique M-mode and two-dimensional echocardiographic findings. Clinical cardiology. 1981 Jan:4(1):34-8 [PubMed PMID: 6894413]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHabib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, Bongiorni MG, Casalta JP, Del Zotti F, Dulgheru R, El Khoury G, Erba PA, Iung B, Miro JM, Mulder BJ, Plonska-Gosciniak E, Price S, Roos-Hesselink J, Snygg-Martin U, Thuny F, Tornos Mas P, Vilacosta I, Zamorano JL, ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). European heart journal. 2015 Nov 21:36(44):3075-3128. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319. Epub 2015 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 26320109]

Moreillon P, Que YA. Infective endocarditis. Lancet (London, England). 2004 Jan 10:363(9403):139-49 [PubMed PMID: 14726169]

Federspiel JJ, Stearns SC, Peppercorn AF, Chu VH, Fowler VG Jr. Increasing US rates of endocarditis with Staphylococcus aureus: 1999-2008. Archives of internal medicine. 2012 Feb 27:172(4):363-5. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1027. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22371926]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMurdoch DR, Corey GR, Hoen B, Miró JM, Fowler VG Jr, Bayer AS, Karchmer AW, Olaison L, Pappas PA, Moreillon P, Chambers ST, Chu VH, Falcó V, Holland DJ, Jones P, Klein JL, Raymond NJ, Read KM, Tripodi MF, Utili R, Wang A, Woods CW, Cabell CH, International Collaboration on Endocarditis-Prospective Cohort Study (ICE-PCS) Investigators. Clinical presentation, etiology, and outcome of infective endocarditis in the 21st century: the International Collaboration on Endocarditis-Prospective Cohort Study. Archives of internal medicine. 2009 Mar 9:169(5):463-73. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.603. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19273776]

Benito N, Miró JM, de Lazzari E, Cabell CH, del Río A, Altclas J, Commerford P, Delahaye F, Dragulescu S, Giamarellou H, Habib G, Kamarulzaman A, Kumar AS, Nacinovich FM, Suter F, Tribouilloy C, Venugopal K, Moreno A, Fowler VG Jr, ICE-PCS (International Collaboration on Endocarditis Prospective Cohort Study) Investigators. Health care-associated native valve endocarditis: importance of non-nosocomial acquisition. Annals of internal medicine. 2009 May 5:150(9):586-94 [PubMed PMID: 19414837]

González Vílchez FJ, Martín Durán R, Delgado Ramis C, Vázquez de Prada Tiffe JA, Ochoteco Azcárate A, Zarauza Navarro J, Sánchez González A. [Active infective endocarditis complicated by paravalvular abscess. Review of 40 cases]. Revista espanola de cardiologia. 1991 May:44(5):306-12 [PubMed PMID: 1852959]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNand N, Singla SK, Magu S. Cardiac Abscess with Ventricular Aneurysm Secondary to Old Myocardial Infarction. The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 2017 May:65(5):95-96 [PubMed PMID: 28598059]

Gnann JW, Dismukes WE. Prosthetic valve endocarditis: an overview. Herz. 1983 Dec:8(6):320-31 [PubMed PMID: 6363238]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePant S, Patel NJ, Deshmukh A, Golwala H, Patel N, Badheka A, Hirsch GA, Mehta JL. Trends in infective endocarditis incidence, microbiology, and valve replacement in the United States from 2000 to 2011. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2015 May 19:65(19):2070-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.518. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25975469]

Que YA, Haefliger JA, Piroth L, François P, Widmer E, Entenza JM, Sinha B, Herrmann M, Francioli P, Vaudaux P, Moreillon P. Fibrinogen and fibronectin binding cooperate for valve infection and invasion in Staphylococcus aureus experimental endocarditis. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005 May 16:201(10):1627-35 [PubMed PMID: 15897276]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceElgharably H, Hussain ST, Shrestha NK, Blackstone EH, Pettersson GB. Current Hypotheses in Cardiac Surgery: Biofilm in Infective Endocarditis. Seminars in thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2016 Spring:28(1):56-9. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2015.12.005. Epub 2015 Dec 11 [PubMed PMID: 27568136]

Mildvan D, Goldberg E, Berger M, Altchek MR, Lukban SB. Diagnosis and successful management of septal myocardial abscess: a complication of bacterial endocarditis. The American journal of the medical sciences. 1977 Nov-Dec:274(3):311-6 [PubMed PMID: 610417]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceArnett EN, Roberts WC. Valve ring abscess in active infective endocarditis. Frequency, location, and clues to clinical diagnosis from the study of 95 necropsy patients. Circulation. 1976 Jul:54(1):140-5 [PubMed PMID: 1277418]

Atik FA,Campos VG,da Cunha CR,de Oliveira FB,Otto ME,Monte GU, Unusual mechanism of myocardial infarction in prosthetic valve endocarditis. International medical case reports journal. 2015; [PubMed PMID: 26045678]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDurack DT, Lukes AS, Bright DK. New criteria for diagnosis of infective endocarditis: utilization of specific echocardiographic findings. Duke Endocarditis Service. The American journal of medicine. 1994 Mar:96(3):200-9 [PubMed PMID: 8154507]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCahill TJ, Prendergast BD. Infective endocarditis. Lancet (London, England). 2016 Feb 27:387(10021):882-93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00067-7. Epub 2015 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 26341945]

Muñoz P, Bouza E, Marín M, Alcalá L, Rodríguez Créixems M, Valerio M, Pinto A, Group for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the Gregorio Marañón Hospital. Heart valves should not be routinely cultured. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2008 Sep:46(9):2897-901. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02173-07. Epub 2008 Jul 16 [PubMed PMID: 18632908]

Meine TJ,Nettles RE,Anderson DJ,Cabell CH,Corey GR,Sexton DJ,Wang A, Cardiac conduction abnormalities in endocarditis defined by the Duke criteria. American heart journal. 2001 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 11479467]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDaniell JE, Nelson BS, Ferry D. ED identification of cardiac septal abscess using conduction block on ECG. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2000 Oct:18(6):730-4 [PubMed PMID: 11043631]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFouchard J, Ponsonaille J, Mujica J, Paraiso N, Guerinon J, Iris L, Vial F. [Atrio-ventricular block due to septal abscess]. Coeur et medecine interne. 1973 Oct:12(4):679-87 [PubMed PMID: 4802091]

Brown RE, Chiaco JM, Dillon JL, Catherwood E, Ornvold K. Infective Endocarditis Presenting as Complete Heart Block With an Unexpected Finding of a Cardiac Abscess and Purulent Pericarditis. Journal of clinical medicine research. 2015 Nov:7(11):890-5. doi: 10.14740/jocmr2228w. Epub 2015 Sep 25 [PubMed PMID: 26491503]

Blumberg EA, Karalis DA, Chandrasekaran K, Wahl JM, Vilaro J, Covalesky VA, Mintz GS. Endocarditis-associated paravalvular abscesses. Do clinical parameters predict the presence of abscess? Chest. 1995 Apr:107(4):898-903 [PubMed PMID: 7705150]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceEllis SG, Goldstein J, Popp RL. Detection of endocarditis-associated perivalvular abscesses by two-dimensional echocardiography. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1985 Mar:5(3):647-53 [PubMed PMID: 3973262]

Jariwala P,Punjani A,Mirza S,Harikishan B,Madhawar DB, Myocardial abscess secondary to staphylococcal septicemia: diagnosis with 3D echocardiography. Indian heart journal. 2013 Jan-Feb; [PubMed PMID: 23438629]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBaddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, Fowler VG Jr, Tleyjeh IM, Rybak MJ, Barsic B, Lockhart PB, Gewitz MH, Levison ME, Bolger AF, Steckelberg JM, Baltimore RS, Fink AM, O'Gara P, Taubert KA, American Heart Association Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and Stroke Council. Infective Endocarditis in Adults: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015 Oct 13:132(15):1435-86. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000296. Epub 2015 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 26373316]

Daniel WG, Mügge A, Martin RP, Lindert O, Hausmann D, Nonnast-Daniel B, Laas J, Lichtlen PR. Improvement in the diagnosis of abscesses associated with endocarditis by transesophageal echocardiography. The New England journal of medicine. 1991 Mar 21:324(12):795-800 [PubMed PMID: 1997851]

Murillo H, Restrepo CS, Marmol-Velez JA, Vargas D, Ocazionez D, Martinez-Jimenez S, Reddick RL, Baxi AJ. Infectious Diseases of the Heart: Pathophysiology, Clinical and Imaging Overview. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2016 Jul-Aug:36(4):963-83. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016150225. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27399236]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCerqueira MD, Jacobson AF. Indium-111 leukocyte scintigraphic detection of myocardial abscess formation in patients with endocarditis. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 1989 May:30(5):703-6 [PubMed PMID: 2715834]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShackcloth MJ, Dihmis WC. Contained rupture of a myocardial abscess in the free wall of the left ventricle. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2001 Aug:72(2):617-9 [PubMed PMID: 11515915]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYamamoto S, Hosokawa N, Sogi M, Inakaku M, Imoto K, Ohji G, Doi A, Iwabuchi S, Iwata K. Impact of infectious diseases service consultation on diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Scandinavian journal of infectious diseases. 2012 Apr:44(4):270-5. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2011.638317. Epub 2011 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 22176644]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSande MA, Courtney KB. Nafcillin-gentamicin synergism in experimental staphylococcal endocarditis. The Journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 1976 Jul:88(1):118-24 [PubMed PMID: 1047088]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceArita M, Kusuyama Y, Takatsuji M, Kawazoe K, Masuyama Y. Septal myocardial abscess and infectious pericarditis in a case of bacterial endocarditis. Japanese circulation journal. 1985 Apr:49(4):451-5 [PubMed PMID: 4009931]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSamol A, Kaese S, Bloch J, Görlich D, Peters G, Waltenberger J, Baumgartner H, Reinecke H, Lebiedz P. Infective endocarditis on ICU: risk factors, outcome and long-term follow-up. Infection. 2015 Jun:43(3):287-95. doi: 10.1007/s15010-014-0715-0. Epub 2015 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 25575463]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMullany CJ, Chua YL, Schaff HV, Steckelberg JM, Ilstrup DM, Orszulak TA, Danielson GK, Puga FJ. Early and late survival after surgical treatment of culture-positive active endocarditis. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 1995 Jun:70(6):517-25 [PubMed PMID: 7776709]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGeorges H, Leroy O, Airapetian N, Lamblin N, Zogheib E, Devos P, Preau S, Hauts de France endocarditis study group. Outcome and prognostic factors of patients with right-sided infective endocarditis requiring intensive care unit admission. BMC infectious diseases. 2018 Feb 21:18(1):85. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-2989-9. Epub 2018 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 29466956]

Richey R, Wray D, Stokes T, Guideline Development Group. Prophylaxis against infective endocarditis: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2008 Apr 5:336(7647):770-1. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39510.423148.AD. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18390528]

Cahill TJ, Baddour LM, Habib G, Hoen B, Salaun E, Pettersson GB, Schäfers HJ, Prendergast BD. Challenges in Infective Endocarditis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2017 Jan 24:69(3):325-344. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.066. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28104075]

Bayliss R, Clarke C, Oakley C, Somerville W, Whitfield AG. The teeth and infective endocarditis. British heart journal. 1983 Dec:50(6):506-12 [PubMed PMID: 6360190]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, Lockhart PB, Baddour LM, Levison M, Bolger A, Cabell CH, Takahashi M, Baltimore RS, Newburger JW, Strom BL, Tani LY, Gerber M, Bonow RO, Pallasch T, Shulman ST, Rowley AH, Burns JC, Ferrieri P, Gardner T, Goff D, Durack DT, American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2007 Oct 9:116(15):1736-54 [PubMed PMID: 17446442]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYanagawa B, Bahji A, Lamba W, Tan DH, Cheema A, Syed I, Verma S. Endocarditis in the setting of IDU: multidisciplinary management. Current opinion in cardiology. 2018 Mar:33(2):140-147. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000493. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29232248]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSmith MA, Smith TL, Davidson BT. Managing the infected heart. Critical care nursing clinics of North America. 2007 Mar:19(1):99-106 [PubMed PMID: 17338955]