Introduction

Eyelid lacerations are managed differently depending on the injury's depth, width, and location. Surgical management is broken down into these categories: laceration without eyelid margin involvement, laceration with eyelid margin involvement, and laceration with nasolacrimal system involvement.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

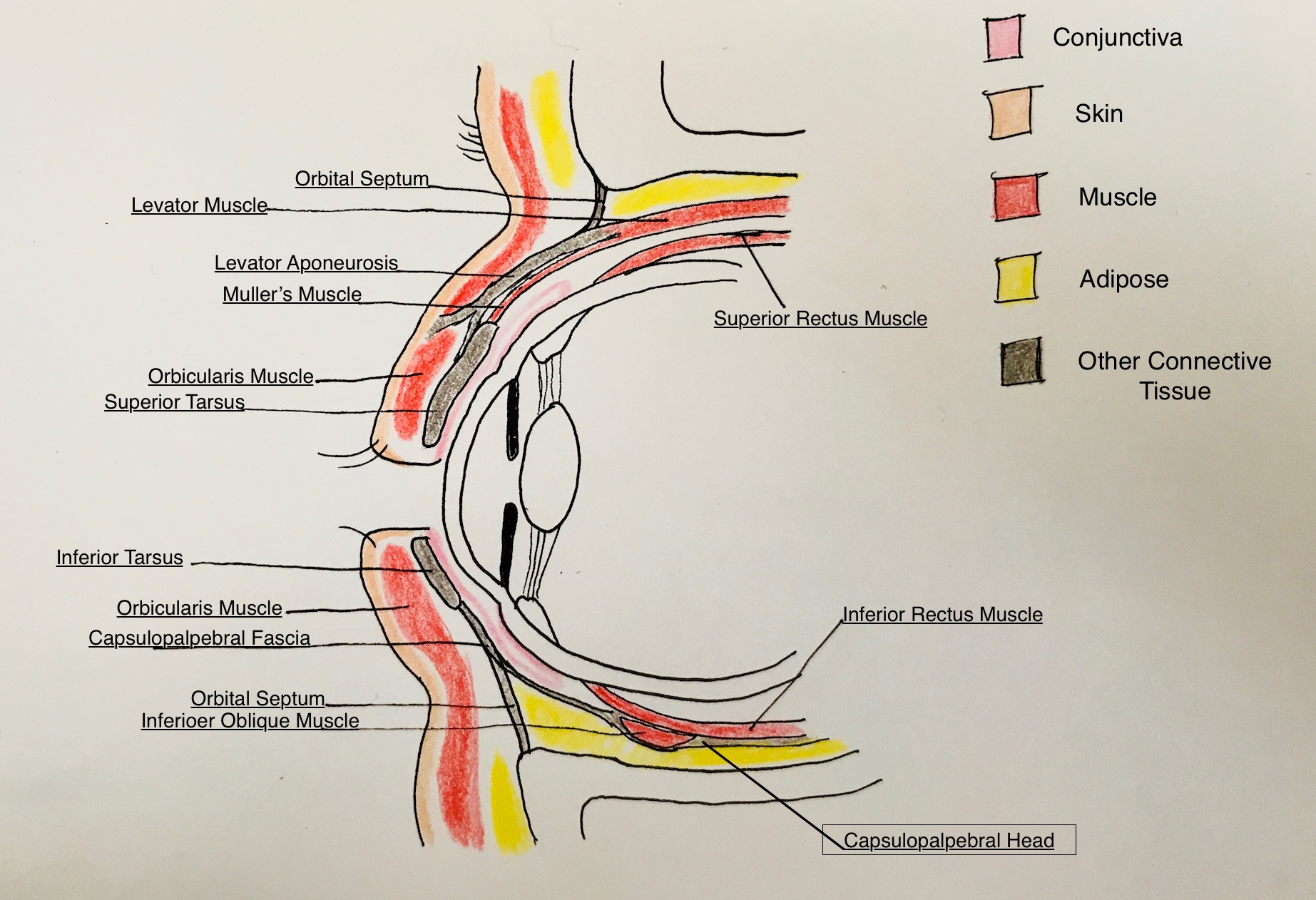

It is important to be proficient in eyelid anatomy when addressing an eyelid laceration (see Image. Eyelid Anatomy). The eyelid has multiple layers that serve different functions, as described below. Please see the eyelid anatomy illustration for correlation.

Skin/Subcutaneous Tissue

The eyelid skin is unique because it has no subcutaneous fat and is thus the thinnest layer of the body's skin. The skin overlying the tarsus tends to be firmly attached to the underlying tissue. In contrast, the skin above the tarsal plate over the orbital septum is loosely attached to underlying tissue, giving rise to a potential space for fluid to collect in trauma/edema. Because eyelid skin is very thin, a smaller diameter suture is required, and smaller bites are taken when approximating lacerations that only involve eyelid skin.

Protractors

Directly under the upper and lower eyelid skin is the orbicularis oculi muscle. This is the main protractor muscle of the eyelid (eyelid closure). The orbicularis oculi muscle is a large, thin, circular muscle divided into pretarsal, pre-septal, and orbital parts. The pretarsal and pre-septal parts are responsible for involuntary eyelid closure (blinking). The orbital portion is primarily responsible for voluntary/forced eyelid closure.

Orbital Septum

A thin, fibrous connective tissue layer separates anterior eyelid structures from intra-orbital structures. The upper orbital septum connects the periosteum of the superior orbital rim to the levator aponeurosis above the superior tarsal border (though this has racial variance). The lower orbital septum connects the periosteum of the inferior orbital rim to the capsulopalpebral fascia just below the inferior tarsal border.

Orbital Fat

This is located immediately posterior to the orbital septum and anterior to the levator aponeurosis in the upper lid and capsulopalpebral fascia of the lower lid. In the upper lid, there are discrete nasal and central fat pads. The lower eyelid has 3 fat pads: nasal, central, and temporal. Thin fibrous capsules surround the pads. The central orbital fat pad is an important landmark in lid laceration repair due to its locations directly posterior to the orbital septum and anterior to the levator aponeurosis.

Retractors

Upper Eyelid

The levator muscle originates in the orbit apex, travels forward over the eyeball, and splits into 2 different structures: the levator aponeurosis anteriorly and the superior tarsal muscle (Muller's muscle) posteriorly. The split occurs superiorly at the Whitnall ligament and inferiorly at the Lockwood ligament.

The levator aponeurosis continues inferiorly and splits into an anterior and posterior portion near the upper tarsal border. The anterior portion of the levator aponeurosis inserts into the pretarsal orbicularis and skin to form the upper eyelid crease. The posterior portion of the aponeurosis inserts into the upper anterior surface of the tarsal plate.

Muller's muscle extends from the undersurface of the levator aponeurosis at the level of the Whitnall ligament and inserts along the upper eyelid superior tarsal margin. It is a sympathetically innervated retractor muscle of the upper eyelid.

Lower Eyelid

The capsulopalpebral fascia is analogous to the levator aponeurosis in the upper eyelid. Its fibers originate from attachments to the inferior rectus muscle. It extends forward, envelops the inferior oblique muscle, forms the Lockwood ligament, and continues anteriorly, attaching to the orbital septum and inferior conjunctival fornix before finally inserting at the inferior tarsal border. The inferior tarsal muscle is analogous to the Muller's muscle in the upper eyelid. This muscle is poorly developed and runs posterior to the capsulopalpebral fascia of the lower eyelid.

Tarsus

The tarsal plates serve as the main structural components of the eyelids. They are made of dense connective tissue and contain the Meibomian glands and eyelash follicles. The tarsal plate of the upper eyelid is 10 mm to 12 mm vertically in the center of the eyelid, and the tarsal plate of the lower eyelid is up to 4 mm vertically in the central eyelid. Both tarsal plates have rigid attachments to the periosteum via the medial and lateral canthal tendons.

Conjunctiva

This non-keratinizing squamous epithelium lines the inner surface of the eyelids and continues to cover the anterior surface of the eyeball, where it terminates at the edge of the cornea. It contains mucin-secreting goblet cells and accessory lacrimal glands that assist in keeping ocular tissues lubricated.

In the nasolacrimal system (not represented in the illustration), both the upper and lower eyelids have small openings on the surface of the eyelid margin near the medial canthus. These are called puncta. The puncta leads to a drainage tube called the canaliculus, which eventually drains into the lacrimal sac and out of the nose via the nasolacrimal duct. Within the eyelid, the canaliculus travels 2 mm inferiorly from the punctum, then turns 90 degrees medially and travels 8 mm to 10 mm before reaching the common canaliculus (where both upper and lower canaliculi meet). The common canaliculus drains tears into the lacrimal sac and inferiorly into the nasolacrimal duct. The fluid can then exit underneath the inferior turbinate in the nose.[1][2][3][4]

Indications

Any injury that disrupts the structure or function of the eyelids can cause the condition. Generally, an eyelid skin laceration greater or equal to 2 linear millimeters requires repair.

Contraindications

There are no absolute contraindications to eyelid laceration repair; however, in patients with concurrent globe rupture, the globe should be evaluated and repaired before any lid procedure. Lacerations secondary to heavy contamination or human/animal bites may need minimal necrotic tissue debridement, but a primary repair is often still performed. Nonetheless, contaminated wounds may be left open for delayed repair. Using local with epinephrine is relatively contraindicated in patients with Raynaud phenomenon, sickle cell disease, arteritis, or severe microvascular disease. However, necrosis of the eyelid following lidocaine with epinephrine administration is rare.

Equipment

Equipment needed for eyelid laceration repairs include:

- Castroviejo needle driver

- Castroviejo 0.5 mm forceps

- Suture (6-0 silk, 6-0 plain gut, 6-0 polyglactin)

- Cautery

- Stents (if needed)

- Standard prep materials for the sterile procedure

Personnel

The emergency room clinician, general plastic surgery, or primary care providers can repair non-marginal and non-canalicular system-involving lacerations involving eyelid skin. An ophthalmologist or oculofacial plastic surgeon should perform complex lacerations involving the eyelid margin, canalicular system, or canthal tendons.

Preparation

Consider tetanus prophylaxis. Obtain appropriate radiologic studies. Determine the appropriate setting for repair, such as operating room (OR) versus bedside. Indications for OR repair include nasolacrimal system involvement, levator aponeurosis/superior rectus involvement, violation of orbital septum/visible orbital fat, canthal tendon avulsion, extensive tissue loss (more than one-third of the eyelid).

- Position the patient in the supine position.

- Instill topical anesthetic in each eye. Place a protective scleral shell over the affected eye. Irrigate the surrounding skin and clean it with a full-strength povidone-iodine solution. Ensure any foreign body or particulate matter is evacuated from the wound. Isolate the area with sterile drapes.

- Pack the nasal cavity with oxymetazoline and 4% lidocaine-soaked neuro sponges if the canalicular system is involved.

- Administer local subcutaneous anesthetic (2% lidocaine with 1 in 100,000 epinephrine) using the minimal amount necessary for adequate anesthesia.

Technique or Treatment

Simple, Superficial Eyelid Laceration Repair

Reapproximate skin edges with simple interrupted sutures using 6-0 silk or 6-0 plain gut sutures. Be sure to evert the skin edges. Take small bites (approximately 1 mm from the skin edge) and space sutures 2 mm to 3 mm apart. Avoid tightly tying sutures to the skin. Tight sutures can strangulate delicate tissue. The silk suture needs to be removed. The plain gut suture is absorbable and is preferred if the patient is unreliable to follow-up for suture removal.

Eyelid Margin Involving Laceration

Many techniques are commonly employed to approximate the edges of an eyelid margin laceration.

- Using a 6-0 Silk suture, re-approximate the edges of the eyelid margin by placing 1 simple interrupted suture from gray line to gray line. Do not tie the suture. See Image 2a.

- Then, place partial-thickness simple interrupted sutures using 6-0 Vicryl to approximate the edges of the tarsal plate. Tie these sutures and cut the ends short. This is important for the structural integrity of the eyelid.

- Place an additional marginal 6-0 silk suture parallel to the first but closer to the lash line.

- Suture skin as described above.

Eyelid Laceration with Canalicular Involvement

Dilate both upper and lower puncta. If there is an un-involved punctum, probe it to the sac and irrigate to ensure no underlying blockages. Then, identify the medial and lateral ends of the lacerated canaliculus. A miniaturized stent can be used if only 1 canaliculus is involved. Silicone tubing or a Crawford stent can be used if both are involved. See below for stenting techniques for miniature and Crawford Stent. Suture skin as described above in simple laceration repair.

Miniature stent: Advance a stent through the punctum of the lacerated canaliculus and out the distal end. Then, insert a stent into the canaliculus opening of the lacerated lateral edge. Ensure the stent is seated in the punctum. Place several 6-0 polyglactin sutures using a curved needle to anastomose the cut edges of the canaliculus and re-approximate the surrounding tissue. Leave these untied. Then, interrupted buried 5-0 polyglactin sutures were added to reinforce the medial canthal tendon. After all deep sutures are placed, tie and trim all sutures.

Crawford Stent: Place the stent's first end through the lacerated canaliculus's punctum and out the distal end. Then, pass the same end through the previously identified proximal end and advance through the lacrimal and nasal lacrimal duct. Retrieve the end of the stent from the nasal cavity. Pass the other end of the stent similarly through the intact canaliculus. Tie and trim ends in the nose just before skin closure.[5][6][7][2][8][9]

Complications

Complications of eyelid lacerations that do not involve the canalicular system include missed injury, infection, eyelid notching, irregular eyelid contour, lagophthalmos, exposure keratopathy, septal perforation, prolapse of orbital fat, corneal injury, shortening of eyelid fornices, wound dehiscence, entropion, trichiasis, and hemorrhage. Additional complications include lacerations involving the canalicular system, such as epiphora, stent migration, and epistaxis.[10]

Clinical Significance

Maintaining the proper position and structure of the eyelid is extremely important for adequate tear film, tear drainage, protection of ocular surfaces, and cosmesis. Eyelid lacerations disrupt the normal eyelid anatomy and require careful repair to prevent ocular surface decompensation and unnatural cosmesis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with eyelid lacerations often visit the emergency department or the urgent clinic. The emergency department physician may manage a simple eyelid laceration, but all other lacerations should be referred to the ophthalmologist or plastic surgeon. Before any repair, the ophthalmic nurse should assess the patient's visual acuity. Complex eyelid lacerations are often associated with other eye injuries requiring a full evaluation before repair. The outlook for simple eyelid lacerations is excellent. All interprofessional team members, including clinicians, specialists, mid-level providers, pharmacists, and nursing staff, must work as a cohesive unit to optimize patient outcomes in these procedures.

Media

References

Ko AC, Satterfield KR, Korn BS, Kikkawa DO. Eyelid and Periorbital Soft Tissue Trauma. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2017 Nov:25(4):605-616. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2017.06.011. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28941512]

Shah SM, Shah MA, Shah PD, Patel KB. Successful repair of injury to the eyelid, lacrimal passage, and extraocular muscle. GMS ophthalmology cases. 2016:6():Doc04. doi: 10.3205/oc000041. Epub 2016 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 27625963]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChoi SH, Gu JH, Kang DH. Analysis of Traffic Accident-Related Facial Trauma. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2016 Oct:27(7):1682-1685 [PubMed PMID: 27438456]

Sadiq MA, Corkin F, Mantagos IS. Eyelid Lacerations Due to Dog Bite in Children. Journal of pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. 2015 Nov-Dec:52(6):360-3. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20150901-02. Epub 2015 Sep 9 [PubMed PMID: 26371465]

Anneberg M, Heje JM, Akram J. [Treatment of traumatic facial injuries]. Ugeskrift for laeger. 2014 Sep 22:176(39):. pii: V05140308. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25294326]

Pargament JM, Armenia J, Nerad JA. Physical and chemical injuries to eyes and eyelids. Clinics in dermatology. 2015 Mar-Apr:33(2):234-7. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2014.10.015. Epub 2015 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 25704943]

Örge FH, Dar SA. Canalicular laceration repair using a viscoelastic injection to locate and dilate the proximal torn edge. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2015 Jun:19(3):217-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2015.02.013. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26059664]

Batur M, Seven E, Aycan A, Çinal A, Yaşar T. Posttraumatic Oculorrhea From the Eyelid. Pediatric emergency care. 2018 Aug:34(8):e150-e151. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001040. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28121972]

Mishra K, Mathai M, Della Rocca RC, Reddy HS. Improving Resident Performance in Oculoplastic Surgery: A New Curriculum Using Surgical Wet Laboratory Videos. Journal of surgical education. 2017 Sep-Oct:74(5):837-842. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.02.009. Epub 2017 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 28284655]

Chiang E, Bee C, Harris GJ, Wells TS. Does delayed repair of eyelid lacerations compromise outcome? The American journal of emergency medicine. 2017 Nov:35(11):1766-1767. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.04.062. Epub 2017 Apr 26 [PubMed PMID: 28473278]