Introduction

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is the most common histiocytic disorder where langerin-positive cells coalesce as granulomatous lesions and deposit in various tissues throughout the body as inflammatory infiltrates. Affected organs include but are not limited to the skin, liver, gastrointestinal tract, and central nervous system (CNS) structures, such as the skull and pituitary gland. Arriving at a diagnosis of LCH requires a coordinated effort amongst an interprofessional team, beginning with a comprehensive review by a trained pathologist to perform a review of the morphologic immunohistochemical and molecular data on a sample for each individual patient with suspected LCH. Once LCh is established, providers must be aware of the differences in management between children and adults and (in adults) the difference between pulmonary and non-pulmonary LCH. Referral and long-term follow-up with an experienced hematologist are essential for the successful management of LCH.[1][2][3][4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

There are numerous theories as to the precise origin of LCH. One of the working theories is that a clonal expansion of CD1a and CD207-positive myeloid-committed hematopoietic progenitors in the bone marrow compartment results in the differentiation into monocytes, which then circulate as Langerhans cells.[5] An even deeper investigation into this process has led to the proposition of an interplay between clonal hematopoiesis (specifically with TET2 mutations) and, upon monocyte differentiation, the secondary acquisition of a BRAF (or other MAP Kinase pathway) mutation. This essentially amounts to a clonal monocytosis and, upon monocyte release into the circulation, circulating LCH.[6]

Epidemiology

LCH remains a rare diagnosis, occurring only in up to 8.9 per million children under the age of 15 with a median age of 3 years when diagnosed. LCH is even less common in adults, occurring in only approximately 0.07 per million annually.[5]

Pathophysiology

LCH begins with a clonal proliferation of mature dendritic cells, most commonly expressing CD1a, CD207, and S100. Once formed, these cells recruit other cell types involved in inflammatory signaling, including T lymphocytes, eosinophils, neutrophils, and macrophages, manifesting as granulomas in various tissues throughout the body; the precise pathophysiology then varies depending on the affected organ.[5] When present in the skin (identified in 5-10% of adults with LCH), it's characterized by an erythematous, scaly rash. On the other hand, Lytic osseous disease is visualized in up to 50% of patients and is regularly identified in the skull and dental structures. Pulmonary LCH (PLCH) is then felt to be a distinct clinic entity and presents in most patients as a single-system disease. While initially considered a reactive smoking-related condition, MAP kinase mutations are now reported in up to 85% of patients, suggesting that this, too, is a clonal neoplastic process.[7]

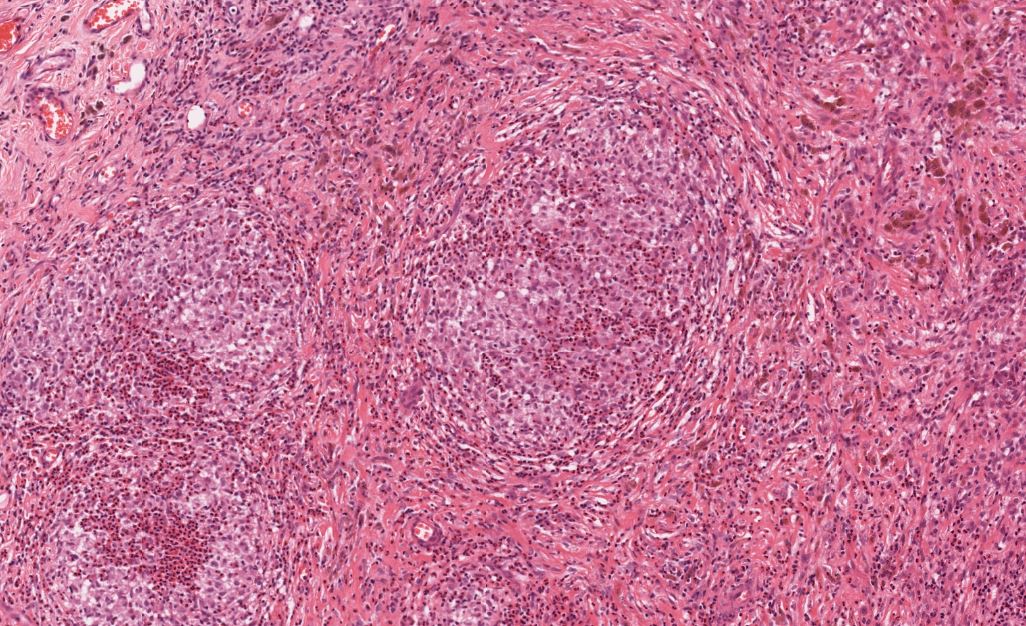

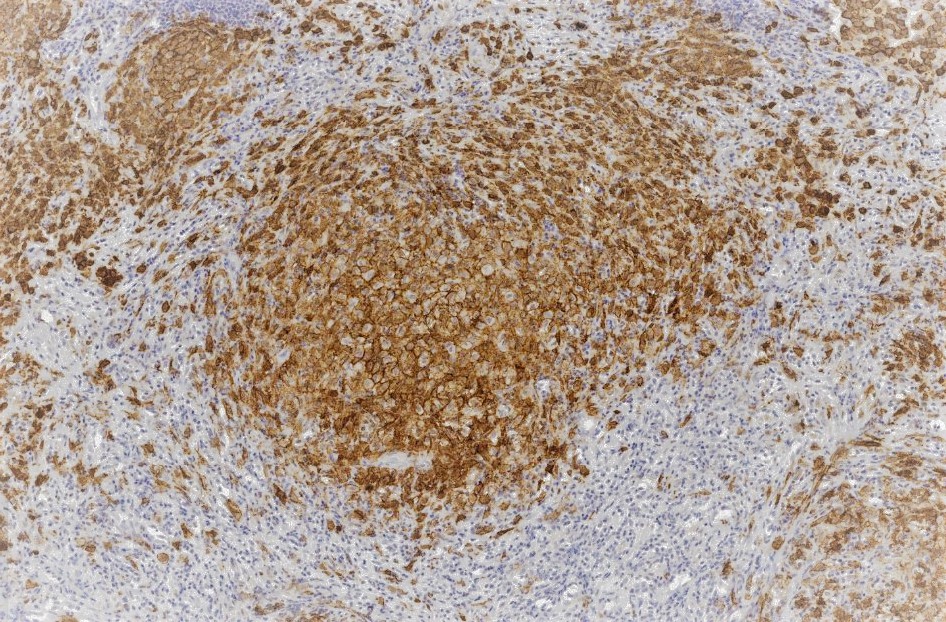

Histopathology

The histological features of LCH are variable and influenced by the age of lesions and their location. Generally speaking, on microscopy, cells are oval or round with a nuclear groove resembling a coffee bean. Characteristic findings by electron microscopy are rod-shaped inclusions in the cytoplasm known as Birbeck granules. LCH coalesces as an eosinophilic granuloma, owing to the influx of eosinophils, macrophages, T cells, and multinucleated cells. Immunostaining highlights the expression of CD1a, Langerin (CD207), and S100. [5]

History and Physical

LCH can impact various organ systems, making clinical presentation variable based on the affected tissue(s), which may include the skin, osseous structures, lymph node(s), or visceral organs such as the lung, liver, and spleen. Presentation also varies by age. Rash, for instance, is common as a presenting symptom in children and may be misdiagnosed as seborrhea or atopic dermatitis that is poorly responsive to traditionally utilized topical therapy. The rash of LCH ranges from a single lesion to widespread involvement. Characteristics include scaly papules, nodules, or plaques and can resemble seborrheic dermatitis. One may distinguish LCH by the presence of petechiae, bloody crusting, or firmly indurated nodules.

Adults generally present after age 40, most of whom have multisystemic disease on presentation. Other myeloproliferative and histiocytic diseases, such as the non-Langerhan cell histiocytosis, may also concur in this population. Pulmonary LCH (PLCH) is a distinct identity that is nearly exclusive to patients with a tobacco use history (present in 90% of patients) and presently with fairly non-specific symptoms in dyspnea on exertion and cough.

Precise definitions for LCH involvement of the liver, spleen, and hematopoietic system were even provided in a 2020 Blood article by Rodriguez-Galindo and Allen. Liver and spleen involvement, for instance, could be diagnosed by enlargement of the organs to >3 and >2 cm below the right and left costal margins, respectively. Hematopoietic involvement, alternatively, required the presence of at least 2 cytopenias.[5] Establishing disease extent at diagnosis in LCH is critical to guiding subsequent management. Providers must, at minimum, determine whether or not single or multi-system disease is present.

The histological and radiographic characteristics of the central nervous system LCH are diverse and vary in their precise location in the brain. For instance, lesions in the cerebral gray and white matter are nodular and present with T2 hyperintensity with T1 hypo- or iso-intensity, while lesions in the cerebellar dentate nuclei display bilateral T1 hyperintensity. An MRI is the gold standard for neural axis imaging, and neuroradiologists are integral to diagnosis.[5][8]

Evaluation

Consensus recommendations set forth by international experts on adult LCH were published in Blood in 2022 and graded categorical recommendations for evaluating patients with suspected and established diagnoses.[7]

Tissue leisonal biopsy is required as a category A recommendation to confirm a diagnosis of LCH. The microscopic features of LCH are described earlier in this chapter, but providers must establish the molecular profiling of disease for every patient, specifically with regard to BRAF/MAPK/ERK mutational status. This is best accomplished through whole exome or integrated genomic-transcriptomic sequencing, which permits the accompanying evaluation for subclonal alterations. Lesions will characteristically stain positive for S-100, CD207 CD1a. Electron microscopy, while not required in light of the advances in immunostaining, will reveal cytoplasmic Birbeck granules. Biopsy is also recommended in PLCH.

Once a tissue diagnosis is confirmed, organ-specific imaging with CT or MRI, at minimum, is recommended (Category A), but whole-body FDG-PET with distal extremity inclusion is useful in providing a full picture of disease (Category B), especially in cases of Langerhans Cell/Erdheim Chester Disease overlap. A brain MRI is also advised in any case of suspected hypothalamic/pituitary involvement (A). Further specialized testing involving invasive or endoscopic procedures is conducted on an individualized basis with regard to the patient's presentation.

Treatment / Management

Management in LCH varies by the initial disease classification, which is summarized as follows:

| LCH Systemic Extent | Definition |

| Single-system unifocal | Single lesion involving one organ |

| Single-system pulmonary | Isolated involvement of the lung(s) |

| Single-system multifocal | >1 lesion involving one organ |

| Multisystemic | ≥2 involved organs |

Please note that the information in this table is adapted from the international expert consensus recommendations for adult LCH diagnosis and treatment.[7](B3)

In single-system unifocal LCH, surgery should be performed with the goal of completion resection, and there is no role for adjuvant systemic therapy. Other options, particularly in the setting of cutaneous disease, include a short course of targeted radiation or intralesional corticosteroids; triamcinolone is commonly employed.

Moving down the chart into single-systemic PLCH, smoking cessation is paramount, including the use of any smoke-generating devices, such as electronic cigarettes and marijuana. Given the causality between tobacco use and LCH, this invention alone can induce complete remission. Single-agent cladribine is also an option. Beyond this, management is mainly supportive and consists of therapies directed at supporting lung functioning, including beta-2 agonists and inhaled corticosteroids.

Lastly, multifocal or multisystemic disease has its own array of options, many of which have been adapted from the pediatric literature for use in adults. The aforementioned International Consensus Guidelines contain a useful summary of these various regimens, specifically those studied in at least 10 patients by name, dosage, and specific disease setting. Among these are vinblastine and methotrexate-containing regimens and (again) single-agent cytarabine. Providers are encouraged to evaluate patients' performance status and, accordingly, anticipate tolerance of such therapies when making a selection.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses of LCH include the following:

- Acrodermatitis enteriropathica

- Acropustulosis of infants

- Congenital candidiasis

- Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis

- Incontinentia pigmenti

- Leukaemia

- Lymphoma

- Mastocytosis

- Myeloma

- Neonatal pustular melanosis

Surgical Oncology

Surgical oncologists should be involved as early as possible in the setting of limited, unifocal single-system disease. This should be approached with the goal of total macroscopic resection, meaning an R1 if possible.

Radiation Oncology

Radiation oncologists should also be involved early in the care/assessment of localized (specifically) cutaneous disease, as a short course of radiation may be offered. Painful or symptomatic lesions in the setting of multisystem LCH may also be radiated.

Medical Oncology

Medical Hematologists should be involved early in the workup of LCH, even in unifocal/limited disease, so that patients' disease may be fully characterized histologically and from a molecular perspective. Medical Hematologists are also essential in guiding disease extent imaging and developing coordinated treatment plans amongst interprofessional teams prior to and throughout the duration of management.

Staging

There is no formal staging system in LCH. A biopsy of the anatomic site suspected to be involved with LCH leading to the most prominent disease extent is heavily advised, even if that means multiple tissue assessments. To provide an example, a patient with confirmed cutaneous LCH but PET-avid or MRI evidence of liver disease should undergo a confirmatory liver biopsy.

Building on this concept and to provide a framework for providers, while LCH cannot be formally staged, it is classifiable by organ system presence by the definitions/subtypes set forth by the aforementioned international expert consensus recommendations for adult LCH diagnosis and treatment described earlier.

Prognosis

The reported prognosis of LCH in the literature varies, owing to differences in baseline disease extent assessment and phenotypic heterogeneity.

Unfortunately, nearly 50% of patients with LCH are prone to various complications which include the following:

-

Musculoskeletal disability

-

Skin scarring

-

Diabetes insipidus

-

Hearing impairment

-

Neuropsychiatric problems like depression, anxiety, and intellectual impairment

-

Pulmonary impairment

-

Secondary malignancies like lymphoblastic leukemia and sodi tumors

-

Growth retardation

-

Liver cirrhosis

Long-term prognosis in both children and adults ultimately depends on the extent of the disease. In one retrospective study, single-system LCH (abbreviated by authors as LCH-SS) was reported to have a favorable prognosis nearing 100% with a <20% rate of recurrence at 5 years. However, multisystem LCH (LCH-MS), specifically involving at-risk organs, such as the spleen, bone marrow, and liver, carries a 5-year overall survival rate ≤77%. Again, this is from retrospective data but does capture a real-world picture of the impact of LCH on patients.[9]

Pearls and Other Issues

The prognosis depends on whether the initial presentation was a low-risk disease (isolated to the skin, lymph nodes, or pituitary gland) or a high-risk disease (involving the spleen, liver, bone marrow, lung, or skeleton). Mortality may be low for isolated lesions (<5%) and as high as 50% for the more widespread disease.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

LCH is a rare disorder characterized by the abnormal proliferation of Langerhans cells, immune cells found in various tissues. This condition can affect individuals of any age, presenting with a spectrum of symptoms ranging from localized bone lesions to multiorgan involvement. Clinicians should be vigilant in recognizing potential manifestations, such as bone pain, skin rash, and organ dysfunction. Diagnosis involves biopsy and immunohistochemistry. Treatment varies based on the extent of involvement, encompassing observation, chemotherapy, and targeted therapies.

Interprofessional collaboration is crucial for optimal patient management. The key is to make an early diagnosis. Healthcare workers must be aware that the rash is the most common presentation. In children, the rash may be misdiagnosed as seborrhea or atopic dermatitis but will not respond to typical treatment for these disorders. The rash of LCH ranges from a single lesion to widespread involvement. Characteristics include scaly papules, nodules, or plaques and can resemble seborrheic dermatitis. One may distinguish LCH by the presence of petechiae, bloody crusting, or firmly indurated nodules.

Regular monitoring and follow-up are essential to assess disease progression and adjust therapeutic strategies accordingly. Despite its rarity, clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for LCH, ensuring prompt intervention for improved outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Wang YC, Li ZZ, Yin CY, Jiang LJ, Wang L. [Langerhans cell histiocytosis involving the oral and maxillofacial region: an analysis of 12 cases]. Zhongguo dang dai er ke za zhi = Chinese journal of contemporary pediatrics. 2019 May:21(5):415-420 [PubMed PMID: 31104654]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRao J, Rao Y, Wang C, Cai Y, Cao G. Cervical langerhans cell histiocytosis mimicking cervical tuberculosis: A Case report. Medicine. 2019 May:98(20):e15690. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015690. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31096509]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAllen A, Matrova E, Ozgen B, Redleaf M, Emmadi R, Saran N. Langerhans' cell histiocytosis of the temporal bone in an adult with central diabetes insipidus. Radiology case reports. 2019 Jul:14(7):847-850. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2019.03.040. Epub 2019 May 2 [PubMed PMID: 31080537]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAllen CE, Merad M, McClain KL. Langerhans-Cell Histiocytosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2018 Aug 30:379(9):856-868. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1607548. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30157397]

Rodriguez-Galindo C, Allen CE. Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2020 Apr 16:135(16):1319-1331. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019000934. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32106306]

Papo M, Diamond EL, Cohen-Aubart F, Emile JF, Roos-Weil D, Gupta N, Durham BH, Ozkaya N, Dogan A, Ulaner GA, Rampal R, Kahn JE, Sené T, Charlotte F, Hervier B, Besnard C, Bernard OA, Settegrana C, Droin N, Hélias-Rodzewicz Z, Amoura Z, Abdel-Wahab O, Haroche J. High prevalence of myeloid neoplasms in adults with non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2017 Aug 24:130(8):1007-1013. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-01-761718. Epub 2017 Jul 5 [PubMed PMID: 28679734]

Goyal G, Tazi A, Go RS, Rech KL, Picarsic JL, Vassallo R, Young JR, Cox CW, Van Laar J, Hermiston ML, Cao XX, Makras P, Kaltsas G, Haroche J, Collin M, McClain KL, Diamond EL, Girschikofsky M. International expert consensus recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults. Blood. 2022 Apr 28:139(17):2601-2621. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021014343. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35271698]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYeh EA, Greenberg J, Abla O, Longoni G, Diamond E, Hermiston M, Tran B, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Allen CE, McClain KL, North American Consortium for Histiocytosis. Evaluation and treatment of Langerhans cell histiocytosis patients with central nervous system abnormalities: Current views and new vistas. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2018 Jan:65(1):. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26784. Epub 2017 Sep 25 [PubMed PMID: 28944988]

Hashimoto K, Nishimura S, Sakata N, Inoue M, Sawada A, Akagi M. Treatment Outcomes of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis: A Retrospective Study. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania). 2021 Apr 7:57(4):. doi: 10.3390/medicina57040356. Epub 2021 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 33917120]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence