Introduction

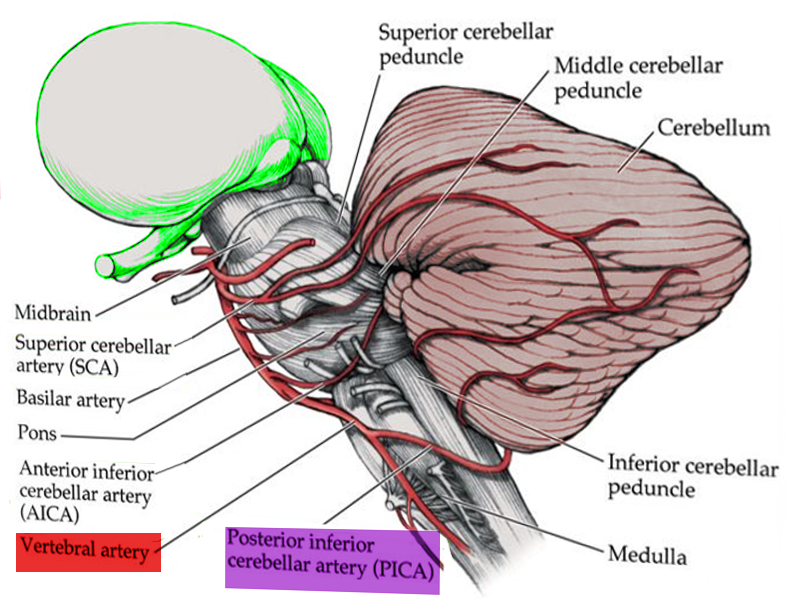

Lateral medullary syndrome (LMS), also called Wallenberg syndrome or posterior inferior cerebellar artery syndrome results from a vascular event in the lateral part of the medulla oblongata. It was named after Adolf Wallenberg (1862-1949), who was a renowned Jewish neurologist and neuroanatomist who practiced in Germany. He first reported the case of LMS. The arteries commonly involved in LMS are the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) or the vertebral artery. Lateral medullary syndrome characteristically has varied neurologic manifestations. The damage is to the inferior cerebellar peduncle and dorsolateral medulla, descending spinal tract, the nucleus of the trigeminal nerve, nuclei, and fibers of the vagus nerves and glossopharyngeal, descending sympathetic tract fibers, spinothalamic tract, and vestibular nuclei.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Etiology of the lateral medullary syndrome include:

- Atherosclerotic disease: can result in thromboembolism, or rarely, hemodynamic failure leading to ischemia.

- Hypertension

- Dissection of vertebral arteries: In a young patient presenting with migraine and signs and symptoms of the LMS, vertebral artery dissection and aneurysm merit consideration.[4]

- Cardiogenic embolism: Cardiac diseases with risk for embolism include atrial fibrillation, mechanical prosthetic valves, left atrial or ventricular thrombus, dilated cardiomyopathy, myocardial infarction, and infective endocarditis. Embolism can also occur in cocaine misuse, neck manipulation, medullary neoplasms, radionecrosis, and hematoma.

- Small vessel disease

- Hypoplastic Vertebral artery: It may rarely contribute to stroke if additional risk factors are present in young patients.[5]

- Moya-moya disease

- Vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia: Patients may present with vertebrobasilar territory ischemia. Risk factors for vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia include male gender, hypertension, smoking, and previous myocardial infarction. It has correlations with aortic dilations, ectatic coronary arteries, Marfan syndrome, late-onset Pompe disease, and the autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.

- Other less common causes of ischemia with a predisposition for the posterior circulation include subclavian steal syndrome, Fabry disease, mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and migraines, and maybe the etiology of the LMS.[6][7][8]

Epidemiology

Posterior circulation strokes represent about 20% of all ischemic strokes. Lateral medullary infarcts occur more frequently in those who consume alcohol.[9] Moreover, in a study, angiograms show that it is more common with vertebral artery disease (67%) as compared to posterior inferior cerebellar artery disease (10%). Also, PICA disease was seen to be more frequently related to cardiogenic embolism as compared to other causes.[6] Between 51% and 94% of the patients with lateral medullary syndrome experience some degree of swallowing difficulty.[1][3]

Pathophysiology

Pathological processes for the development of lateral medullary syndrome include large-vessel infarction (50%), arterial dissection (15%), small vessel infarct (13%), and cardioembolism (5%).

Dysphagia in LMS involves a lack of coordination in pharyngeal and esophageal phases of swallowing. Dysphagia is due to the involvement of swallowing centers in the dorsolateral medulla oblongata. These include the nucleus ambiguous and nucleus tractus solitarius and the reticular formation.

Hiccups are also a clinical feature of the lateral medullary syndrome. The neural structures related to hiccups are unknown, but nucleus ambiguus or adjacent areas that are involved in regulating respiration may have involvement in the generation of the hiccup.

Hyponatremia after a brain injury occurs due to the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) and cerebral salt wasting syndrome. Reports exist of SIADH in patients with lateral medullary infarction. The proposed pathophysiology includes the failure of propagation of non-osmotic stimuli from the carotid sinus through vagal nerve due to the nucleus tractus solitarius lesion in the medulla. This results in the disinhibition of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) secretion by the pituitary gland causing SIADH.[10]

Vertigo, nausea and vomiting, and symptoms like skew deviation, diplopia, and severe gait ataxia could be due to the pathology of the vestibular nuclei or vestibular–cerebellar connections.[1][3][6]

Spinothalamic tract - Contralateral impairment of pain and temperature in trunk and limbs

Trigeminal nerve (V) - Ipsilateral loss of pain and temperature on the face

Vestibular nucleus - Ipsilateral nystagmus, vertigo, nausea, and vomiting

Nucleus ambiguus - Ipsilateral dysphagia, dysarthria, and dysphonia[6][11]

Descending Sympathetic - Ipsilateral Horner syndrome

Cerebellum - Ipsilateral gait ataxia

Glossopharyngeal (IX) - Ipsilateral absent gag reflex and hoarseness

Vagus nerve (X) - Ipsilateral/ deficit of reflex cough test[3]

Trigeminal nerve (V) - Trismus due to masseter and temporalis hyper contraction

History and Physical

The usual symptoms of lateral medullary infarction include vertigo, dizziness, nystagmus, ataxia, nausea and vomiting, dysphagia, and hiccups. Dysphagia is more profound in lateral medullary syndrome patients. Nevertheless, the manifestation is broad and includes dysphonia, facial pain, visual disturbance, and headaches. There is:

- Impairment of pain and thermal sensation over the contralateral side of the trunk and limbs

- Impairment of pain and thermal sensation over the ipsilateral face

- Ipsilateral Horner syndrome

- Ipsilateral limb ataxia

- Dysphagia

- Nystagmus (horizontal or horizontal–rotational, opposite to the side of the lesions, usually more prominent on looking downward)

- Hiccups (can easily be overlooked)

- ipsilateral hyperalgesia

Study shows that the onset of the lateral medullary syndrome is sudden in 75% of patients and gradual in 25% of patients. Sensory signs and symptoms are the most frequent manifestations (96%). Less common clinical presentation includes facial paresis, dysarthria, and eye pathologies such as skew deviation, diplopia, and gaze deviation. Among those with gradual onset, patients usually first have headaches, vertigo, dizziness, or gait ataxia, while sensory clinical features, dysphagia, hoarseness, and hiccups usually occur later.[1][2][6][7][10]

Patients with lateral medullary syndrome show conjugate deviation of eyes towards the side of the lateral medullary infarct. Various types of eye problems correlate with LMS. These are nystagmus, gaze-evoked nystagmus, skew deviation, and ipsipulsion. Among these, ipsipulsion is more specific to LMS.[12]

Evaluation

Evaluation should include a detailed clinical history, physical exam, and appropriate testing, including:

- Evaluation of risk factors: Record risk factors for stroke such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking history, and heart disease. History of neck pain, trauma, or headache, particularly in younger patients, may suggest vertebral dissection.[6][8]

- Complete neurological examination: LMS remains a clinical diagnosis based upon a characteristic history and constellation of physical findings.

- Routine blood investigations, including blood glucose, and serum electrolytes, etc

- Electrocardiogram (EKG) to rule out atrial fibrillation

- Echocardiography (ECHO) and carotid Doppler

- Swallowing evaluation: Clinical and instrumental swallowing evaluations carried out by videofluoroscopy and fiber-endoscopic examination.[3]

- Diagnostic Imaging tests:

Computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain: Brain CT is typically the initial imaging test for lateral medullary syndrome patients. CT gives suboptimal visualization of the posterior fossa structures due to obscuration by artifacts (bony structures), and early ischemic changes may not be visible.[8]

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): MRI provides better visualization of the soft tissue structures as compared to CT scan. MRI aids in diagnosis by improved visualization of the medullary infarction. For example, by the use of imaging protocol fluid attenuation inversion recovery sequences (FLAIR) in the evaluation of infarction.[6][7]

Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DWI): can detect infarct early.

- Neurovascular Studies:

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) examination are advanced imaging studies. They identify the exact location of the lesion.

Treatment / Management

Management includes resuscitation and intensive care unit monitoring. Respiratory failure should remain in mind, and patients followed in the intensive care unit.[9](B3)

Patients should have clinically monitoring for signs of increased intracranial pressure. These include disorientation, lethargy, headache, vomiting. Look for bradycardia, hypertension, or irregular respiratory pattern. Management includes head elevation to 30 degrees, blood-pressure management to maintain cerebral perfusion, hyperventilation, osmotherapy, and sedation. Surgery may be a consideration.

Reperfusion/Thrombolytic therapy: Intravenous thrombolysis with IV recombinant tissue-plasminogen activator (IV-rt-PA), and endovascular thrombectomy may be an option.

Secondary stroke prevention: With antiplatelets, antihypertensives, and statins. Treatment of the cause and vascular risk factors.[8]

Evaluation of enteral nutrition: Patients may require a nasogastric tube.

Dysphagia management: Dietary and/or postural modifications are required. If severe dysphagia is prolonged, conversion to percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) may be required. Swallowing treatment: Active exercises to strengthen swallowing musculature. Botulinum toxin type-A injections have been used to treat severe dysphagia associated with trismus.[1][3](B3)

Low-molecular-weight heparin prophylaxis of deep vein thrombosis.

Speech therapy assessment

Hiccups: There are reports of the use of gabapentin in the treatment of persistent hiccups in cases of LMS.[2](B3)

Medullary infarction can cause autonomic abnormalities leading to acute heart failure. A pacemaker may be required.[13](B3)

Keratitis in LMS can occur due to loss of corneal sensitivity caused by trigeminal neuropathy leading to epithelial erosions. These patients need multidisciplinary management, artificial tears, night creams, autologous serum, and rarely surgical procedures.[11](B3)

The lateral medullary syndrome may cause chronic disabling facial pain. Gabapentin is an option for these patients.

Periodic follow up of the patient to evaluate speech and motor activity.[7]

Differential Diagnosis

- Headache: migraine, cluster headache

- Intracranial hemorrhage

- Malignancy

- Psychiatric conversion disorders

- Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome[8]

- Vasculitis of the large and medium-sized vessels (e.g., giant cell arteritis)

- Vertebral artery dissection

Prognosis

The lateral medullary syndrome has a good prognosis. With improved respiratory care, patients recover and often resume their previous activities. Dysphagia in LMS also has a good prognosis.[1][6]

Complications

- SIADH (rare in lateral medullary syndrome as compared to other stroke patients)

- Neurotrophic keratopathy (corneal damage and infection)[11][14]

- Severe dysphagia

- Trigeminal neuralgia

- Rarely cardiac complications (Nucleus tractus solitarii is involved in cardiovascular regulation)[13]

- Obstructive hydrocephalus

- Respiratory complications (e.g., aspiration pneumonia, respiratory failure, hypoventilation syndrome (Ondine's curse)). Respiratory failure due to autonomic dysfunction can be observed rarely. This can cause apnea and death.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Lateral medullary syndrome patients require physical and occupational therapy until they gradually develop their physical strength. Patients should be aware of secondary stroke prevention strategies. Those with dysphagia should go through dysphagia rehabilitation. Severe dysphagia cases may require a gastrostomy tube. Regular follow up is necessary for a speech evaluation.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Lateral medullary syndrome management requires an interprofessional therapeutic approach. Healthcare professionals should focus on stroke prevention. These include control of risk factors such as smoking and hypertension. Additionally, blood pressure-lowering medication, antithrombotic therapy, and statins are required. Physiotherapy is an essential cornerstone in the management of LMS patients. Inpatient rehabilitation is also necessary. Speech and occupational therapy are crucial for daily living activities. Patients who are not able to swallow my need to see a dietitian. Some patients may need a temporary feeding tube. Long term follow-up is necessary by a neurology nurse to ensure that the patient is recovering. The social worker should be consulted to ensure that the patient's home environment is safe, and there are support services available. Some patients may have had a severe stroke, and the end of life committee should speak to the caregiver about future decisions regarding care. Patients should be followed up by the interprofessional team after hospital discharge until they improve functionally.

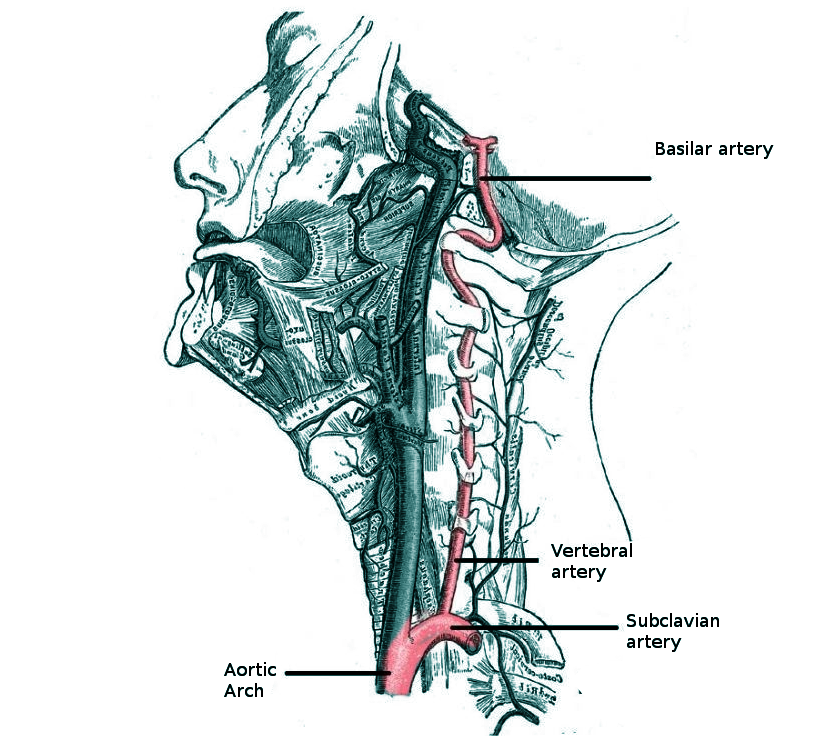

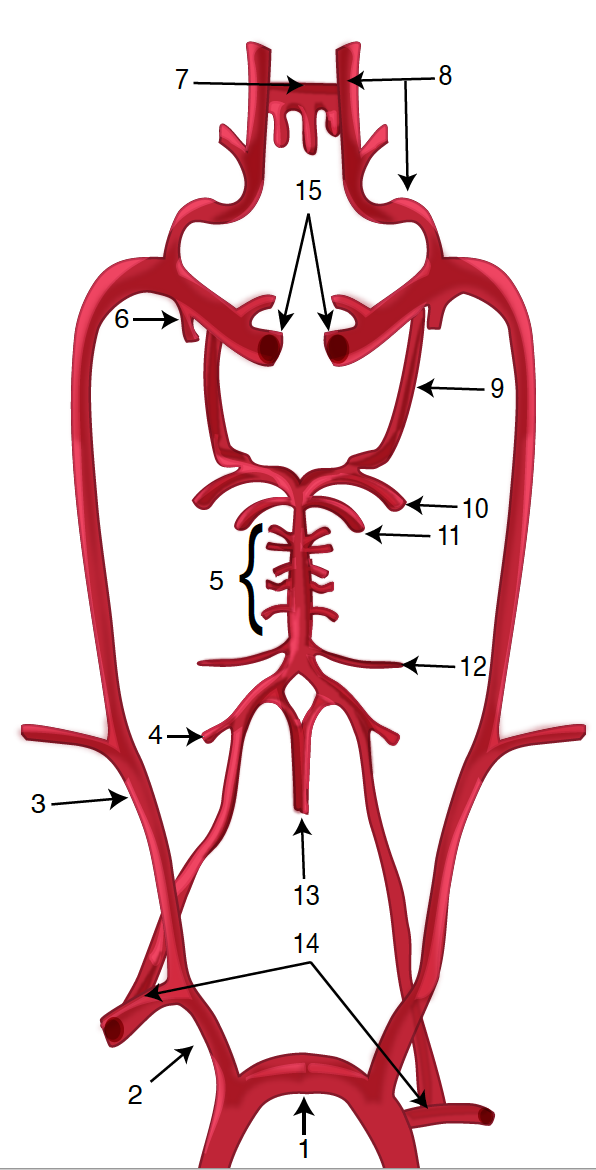

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Diagram of the Brain Blood Circulation. Each number corresponds to the following neuroanatomy: 1) aortic arch; 2) brachiocephalic artery; 3) common carotid artery; 4) posterior inferior cerebellar artery; 5) pontine arteries; 6) anterior choroidal artery; 7) anterior communicating artery; 8) anterior cerebral artery; 9) posterior communicating artery; 10) posterior cerebral artery; 11) superior cerebellar artery; 12) anterior inferior cerebellar artery; 13) anterior spinal artery; 14) arches of vertebral arteries; and 15) internal carotid arteries.

Contributed by O Kuybu, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

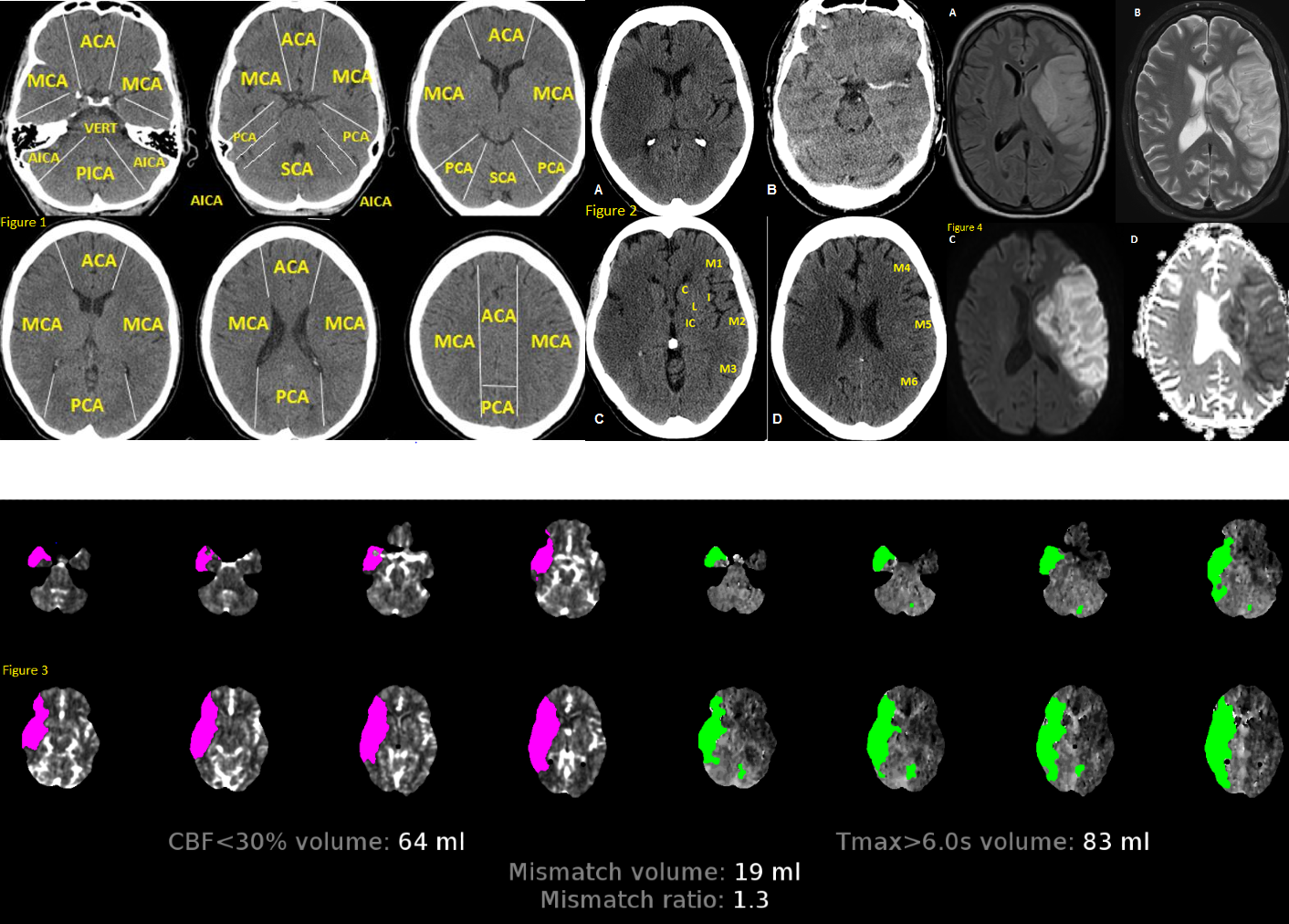

Fig 1. Anatomy of brain vascular territories. ACA: anterior cerebral artery; MCA: middle cerebral artery; PCA: posterior cerebral artery; AICA: anterior inferior cerebellar artery; PICA: posterior inferior cerebellar artery; SCA: superior cerebellar artery. Fig 2. Non-contrast CT shows loss of gray-white matter diffraction in the right MCA territory consistent with acute large right MCA infarction Fig 3. CTP in stroke imaging. The areas of increased MTT, TTP or Tmax and decreased CBV or CBF are considered as infarct core Fig 4. MRI in stroke. There is a large left MCA infarction. Infarction is hypersignal on FLAIR (A) and T2 (B) sequences. Also, there is a mass effect in favour of subacute infarction. The infarction shows “true” diffusion restriction: hyper signal on DWI (C) and hypo signal on ADC map (D). Contributed by Omid Shafaat, M.D.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Kim H, Lee HJ, Park JW. Clinical course and outcome in patients with severe dysphagia after lateral medullary syndrome. Therapeutic advances in neurological disorders. 2018:11():1756286418759864. doi: 10.1177/1756286418759864. Epub 2018 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 29511384]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSampath V, Gowda MR, Vinay HR, Preethi S. Persistent hiccups (singultus) as the presenting symptom of lateral medullary syndrome. Indian journal of psychological medicine. 2014 Jul:36(3):341-3. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.135397. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25035568]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBattel I, Koch I, Biddau F, Carollo C, Piccione F, Meneghello F, Merico A, Palmer K, Marchese Ragona R. Efficacy of botulinum toxin type-A and swallowing treatment for oropharyngeal dysphagia recovery in a patient with lateral medullary syndrome. European journal of physical and rehabilitation medicine. 2017 Oct:53(5):798-801. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.17.04499-9. Epub 2017 Mar 6 [PubMed PMID: 28264544]

Kumar N, Garg RK, Malhotra HS, Lal V, Uniyal R, Pandey S, Rizvi I. Spontaneous Vertebral Artery Dissection and Thrombosis Presenting as Lateral Medullary Syndrome. Journal of neurosciences in rural practice. 2019 Jul:10(3):502-503. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1697243. Epub 2019 Oct 7 [PubMed PMID: 31595124]

Giannopoulos S, Markoula S, Kosmidou M, Pelidou SH, Kyritsis AP. Lateral medullary ischaemic events in young adults with hypoplastic vertebral artery. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2007 Sep:78(9):987-9 [PubMed PMID: 17702781]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKim JS. Pure lateral medullary infarction: clinical-radiological correlation of 130 acute, consecutive patients. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2003 Aug:126(Pt 8):1864-72 [PubMed PMID: 12805095]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceShetty SR, Anusha R, Thomas PS, Babu SG. Wallenberg's syndrome. Journal of neurosciences in rural practice. 2012 Jan:3(1):100-2. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.91980. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22346215]

Nouh A, Remke J, Ruland S. Ischemic posterior circulation stroke: a review of anatomy, clinical presentations, diagnosis, and current management. Frontiers in neurology. 2014:5():30. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00030. Epub 2014 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 24778625]

Aynaci O, Gok F, Yosunkaya A. Management of a patient with Opalski's syndrome in intensive care unit. Clinical case reports. 2017 Sep:5(9):1518-1522. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.1111. Epub 2017 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 28878917]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKim JM, Park KY, Kim DH, Bae JH, Shin DW, Youn YC, Kwon OS. Symptomatic hyponatremia following lateral medullary infarction: a case report. BMC neurology. 2014 May 22:14():111. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-14-111. Epub 2014 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 24886592]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCidad P, Boto A, Del Hierro A, Capote M, Noval S, Garcia A, Santiago S. Unilateral punctate keratitis secondary to Wallenberg Syndrome. Korean journal of ophthalmology : KJO. 2014 Jun:28(3):278-83. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2014.28.3.278. Epub 2014 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 24882965]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePaliwal VK, Kumar S, Gupta DK, Neyaz Z. Ipsipulsion: A forgotten sign of lateral medullary syndrome. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology. 2015 Jul-Sep:18(3):284-5. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.150621. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26425003]

von Heinemann P, Grauer O, Schuierer G, Ritzka M, Bogdahn U, Kaiser B, Schlachetzki F. Recurrent cardiac arrest caused by lateral medulla oblongata infarction. BMJ case reports. 2009:2009():. pii: bcr02.2009.1625. doi: 10.1136/bcr.02.2009.1625. Epub 2009 Oct 12 [PubMed PMID: 21991295]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWu S,Li N,Xia F,Sidlauskas K,Lin X,Qian Y,Gao W,Zhang Q, Neurotrophic keratopathy due to dorsolateral medullary infarction (Wallenberg syndrome): case report and literature review. BMC neurology. 2014 Dec 4; [PubMed PMID: 25472780]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence