Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Arteries

Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Arteries

Introduction

The bony pelvis and lower limbs receive their vascular supply from the distal continuations of the right and left common iliac arteries. The primary blood supply to the bony pelvis is from the divisions of iliac arteries; the lower limbs receive supply via the obturator artery and divisions of the common femoral artery.

The blood supply to the lower limbs and pelvis has several significant medical, musculoskeletal, and surgical considerations that make a thorough understanding of the anatomy vital to patient care. The goal of this article is to provide a review of the arterial supply of the bony pelvis and lower limb to improve practitioner knowledge and medical care.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The Bony Pelvis

The bony pelvis is formed from the ilium, ischium, and pubis, with the sacrum completing the pelvic ring. The arterial supply of the bony pelvis is derived from the distal bifurcation of the aorta, which forms the right and left common iliac arteries. These arteries further subdivide to create the internal and external iliac arteries.

The external iliac artery courses along the pelvic brim, producing the circumflex iliac artery and the pubic branch. The circumflex iliac artery supplies the iliac crest, while the pubic branch supplies the superior pubic ramus. The external iliac artery passes beneath the inguinal ligament and continues as the femoral artery.

The internal iliac artery courses along the posteromedial ischium, bifurcating into the anterior and posterior divisions.[1]

The posterior division of the internal iliac artery gives rise to the iliolumbar artery, superior gluteal artery, and lateral sacral arteries. The iliolumbar artery courses retrograde along the medial aspect of the ilium and lateral aspect of the lumbar vertebrae to supply the superior aspect of the ilium and the lower lumbar vertebrae. The superior gluteal artery exits the pelvis via the superior sciatic foramen superior to the piriformis muscle, producing a nutrient branch to the ilium. The lateral sacral artery courses along the lateral sacrum, supplying the sacrum and forming an anastomotic arterial plexus with the median sacral artery (a branch from the bifurcation of the abdominal aorta).

The anterior division of the internal iliac artery gives rise to the obturator artery and the inferior gluteal artery. The obturator artery traverses the pelvis, exiting through the obturator foramen. Before exiting the pelvis, there may be an anastomotic connection between the obturator artery and the external iliac circulation, known as the accessory obturator artery or corona mortis. The clinical significance of this variant is discussed below.[2] The inferior gluteal artery exits the pelvis via the greater sciatic foramen between the piriformis and ischiococcygeus muscles.

The Femur

The arterial supply to the femur can be divided into thirds. The proximal third of the femur includes the femoral head, neck, the greater and lesser trochanters, and the metaphysis. The medial femoral circumflex artery provides the primary supply to this region; the secondary blood supply is from the lateral femoral circumflex artery and an anastomosis of the inferior gluteal artery and flow through the foveal artery via the ligamentum teres femoris.[3]

There are several important anastomoses near the head and neck of the femur, known as the cruciate anastomosis. This anastomosis involves a confluence of arteries at the level of the lesser trochanter. The cruciate anastomosis is composed of the following vessels: the medial femoral circumflex artery, the lateral femoral circumflex artery, the inferior gluteal artery, and the first perforating artery of the profunda femoris artery.[4] The profunda femoris artery supplies the middle third of the femur.[5]

The distal third of the femur includes the medial and lateral femoral condyles. The medial femoral condyle receives its blood supply from descending genicular artery, a branch of the femoral artery proximal to the adductor hiatus. The superior lateral genicular artery supplies the lateral femoral condyle. These arteries create an anastomosis around the distal femur.[6]

The Gluteal Region

The superior and inferior gluteal arteries provide blood to the gluteal region.

The superior gluteal artery is a branch of the posterior division of the internal iliac artery. It exits the pelvis via the greater sciatic foramen, superior to the piriformis muscle. The artery passes between the gluteus minimus muscle and the gluteus medius muscle. The superior gluteal artery supplies the gluteus minimus, gluteus medius, gluteus maximus, and tensor fascia latae muscles.

The inferior gluteal artery is a branch of the anterior division of the internal iliac artery. It exits the pelvis via the greater sciatic foramen inferior to the piriformis muscle and superior to ischiococcygeus muscle. The artery courses deep to the gluteus maximus muscle and superficial to the muscular external (lateral) rotators of the hip: the superior gemellus, the tendon of the obturator internus, the inferior gemellus, and the quadratus femoris. The inferior gluteal artery supplies the gluteus maximus, the piriformis, the superior gemellus, the obturator internus tendon, the inferior gemellus, and the quadratus femoris muscles, as well as contributing to the vascular supply of the greater trochanter of the femur and sciatic nerve.[7]

The Medial Compartment of the Thigh

The obturator artery exits the pelvis via the obturator canal, a passage in the obturator foramen formed by the obturator membrane. The obturator artery supplies the majority of the contents of the medial compartment of the thigh, including the obturator externus, the pectineus, the adductor magnus, the adductor brevis, the adductor longus, and the gracilis muscles.[8]

The Anterior Compartment of the Thigh

The external iliac artery exits the pelvis deep to the inguinal ligament, becoming the common femoral artery. The common femoral artery lies lateral to the femoral vein and medial to the femoral nerve; it is located within the femoral sheath along with the femoral vein. A useful anatomical mnemonic is NAVEL; from lateral to medial, the femoral nerve, the femoral artery, and the femoral vein (NAV). The EL stands for empty space with lymphatics (i.e., the femoral canal) which contains the lymph node of Cloquet.

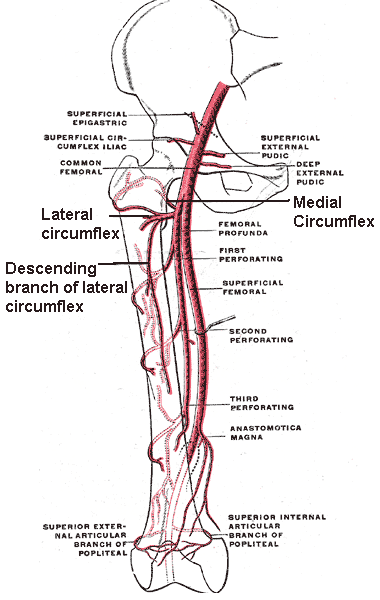

The femoral vein is located halfway between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle. Upon passing beneath the inguinal ligament, the common femoral artery gives rise to the superficial circumflex iliac artery and the superficial epigastric artery. The common femoral artery then gives rise to the profunda femoris artery. The profunda femoris artery gives rise to the medial and lateral femoral circumflex arteries.

The medial femoral circumflex artery supplies the distal iliopsoas muscle, while the iliolumbar artery supplies the proximal portion of this muscle. The lateral femoral circumflex artery supplies the vastus lateralis and rectus femoris muscles. The remainder of the musculature in the anterior compartment of the thigh, including the vastus intermedius, the vastus medialis, and the sartorius muscles, receive their blood supply from the femoral artery.[9]

The Posterior Compartment of the Thigh

The profunda femoris artery gives rise to four perforating arterial branches, which perforate the adductor magnus to supply the posterior compartment of the thigh. Thus, the blood supply to the biceps femoris, the semimembranosus, and the semitendinosus muscles arises primarily from these perforating branches. The semimembranosus and semitendinosus muscles receive an additional blood supply from the inferior gluteal artery.[10] As a historical note, the surgeon John Hunter described the anatomy of the profunda femoris artery, the femoral artery, and the adductor (subsartorial) canal of Hunter. Understanding the anatomy of this region made it possible to amputate the leg at the knee rather than the thigh (as amputation was previously performed). Amputation at the thigh required the use of a crutch to walk. Amputation at the knee made it possible to use a peg leg, making ambulation much easier.

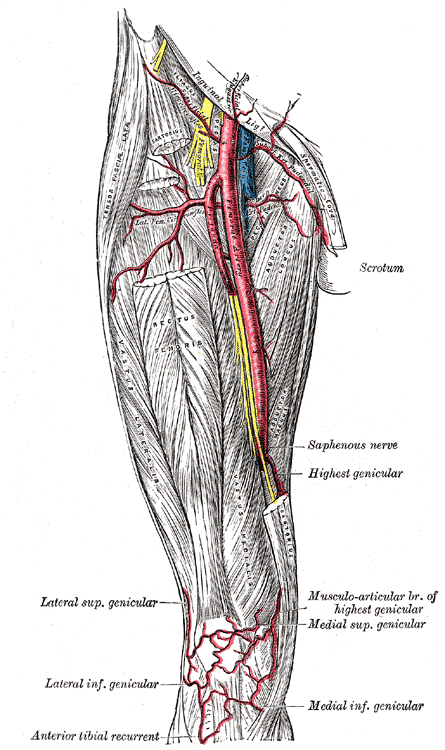

The Popliteal Region and the Knee

In the distal thigh, the femoral artery passes through the adductor hiatus of the adductor magnus muscle to become the popliteal artery. Immediately before passing through the adductor canal, the femoral artery also gives rise to the descending genicular artery, which bifurcates to form the articular and saphenous branches supplying the knee. At the level of the femoral epicondyles, the popliteal artery gives rise to the superior lateral and superior medial genicular arteries. The superior lateral genicular artery forms an anastomosis with the descending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery.

On reaching the level of the tibial plateau, the popliteal artery gives rise to the inferior lateral and inferior medial geniculate arteries. A patellar anastomosis forms from the superior lateral, superior medial, inferior lateral, and inferior medial geniculate arteries, with an additional contribution from the articular branch of the descending genicular artery.

Distal to the lateral and medial inferior genicular arteries, the popliteal artery bifurcates to form the anterior and posterior tibial arteries. The anterior and posterior tibial recurrent arteries arise from the anterior tibial artery. The posterior tibial recurrent artery branches from the anterior tibial artery before it passes through the interosseous membrane. It forms an anastomosis with inferior genicular arteries to supply the tibiofibular joint. The anterior tibial recurrent artery branches from the anterior tibial artery after it passes through the interosseous membrane and contributes to the patellar plexus.[11]

The Tibia

The arterial supply to the tibia can be divided into the branches supplying the proximal fifth, proximal diaphysis, distal diaphysis, and distal fifth. The proximal fifth of the tibia receives its vascular supply from the anterior and posterior tibial arteries and the medial inferior geniculate artery. The proximal diaphysis of the tibia is supplied by anterior and posterior tibial arteries, while the distal diaphysis is supplied almost exclusively by semicircular periosteal branches of the anterior tibial artery. The vascular supply to the distal fifth of the tibia differs between populations. In approximately two-thirds of people, the fibular and anterior tibial arteries combine to supply this region. In the other one-third, only the anterior tibial artery supplies this region.[12]

The Fibula

The primary arterial supply to the fibula is from the fibular (peroneal) artery, although the anterior tibial artery makes proximal contributions.[13]

The Lateral Compartment of the Leg

The peroneus (fibularis) longus and peroneus (fibularis) brevis constitute the muscular content of the lateral compartment of the leg. The fibular artery supplies both muscles. The fibular artery is a tributary of the posterior tibial artery, arising just distal to the interosseous membrane. It courses deep to the fibula and gives rise to perforating branches, which supply the muscles of the lateral compartment of the leg.[14]

The Anterior Compartment of the Leg

The anterior tibial artery gives rise to most of the arterial supply of the anterior compartment of the leg. After passing through the interosseous membrane, the anterior tibial artery courses along the interosseous membrane lateral to the tibialis anterior and medial to the extensor digitorum longus and the extensor hallucis longus muscles. The anterior tibial artery supplies the tibialis anterior, the extensor digitorum longus, the extensor hallucis longus, and the peroneus (fibularis) tertius muscles.[15]

The Superficial Posterior Compartment of the Leg

The plantaris, the gastrocnemius, and the soleus comprise the muscular content of the superficial posterior compartment of the leg. The plantaris and gastrocnemius muscles are supplied by sural arteries, a group of short arteries arising from the popliteal artery. The soleus receives blood from the posterior tibial artery, the popliteal artery, and the peroneal (fibular) artery. The posterior tibial artery courses deep to the soleus and superficial to the deep posterior compartment of the leg.[16]

The Deep Posterior Compartment of the Leg

The popliteus, the flexor hallucis longus, the tibialis posterior, and the flexor digitorum longus muscles form the deep posterior compartment of the leg. The popliteus muscle lies deep to the popliteal artery from which it receives its vascular supply. The posterior tibial artery lies lateral to flexor digitorum longus and medial to tibialis posterior and supplies both of these muscles. The flexor hallucis longus is supplied by the peroneal (fibular) artery, which lies deep to it.[16]

The Tarsal Bones, Metatarsals, and Phalanges

The tarsal, metatarsal, and phalangeal bones receive their blood supply from the dorsalis pedis, the fibular, the posterior tibial, the medial plantar, and the lateral plantar arteries. The blood supply of the periosteal and endosteal tissues often differ, receiving blood from separate anastomotic plexuses.

The talar vascular supply is from the artery of the tarsal sinus (a branch of the fibular artery), branches of the dorsalis pedis artery, the artery of the tarsal canal, and the deltoid branch from the posterior tibial artery.[17] The calcaneus is supplied by the calcaneal anastomosis, which is formed from branches derived from the fibular and posterior tibial arteries.[18] The navicular bone receives blood from branches of the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial arteries.[19] The lateral plantar artery supplies the cuboid.[20]. The cuneiform bones receive their plantar blood supply from the medial plantar artery, and the dorsalis pedis artery supplies the extraosseous tissues.[21]

The dorsal and plantar metatarsal arteries supply the metatarsal bones. The dorsal metatarsal arteries are branches of dorsalis pedis artery, while the plantar metatarsal arteries are branches of the posterior tibial artery.[22] The fifth metatarsal bone receives its blood supply from the fibular artery, the lateral plantar artery, and the dorsalis pedis artery.

Fractures involving the proximal base of the fifth metatarsal are prone to malunion or nonunion, causing avascular necrosis. This tendency is due to a watershed area between the branches supplying this portion of the fifth metatarsal. This topic will have further coverage in the clinical significance section.[23][24]

Phalanges of the foot receive their blood supply from the dorsalis pedis artery and the plantar metatarsal arteries.[25]

The Dorsal Compartment of the Foot

The anterior tibial artery emerges lateral to the tibialis anterior tendon and the extensor hallucis longus tendon and medial to the extensor digitorum tendon in the foot to become the dorsalis pedis artery. The dorsalis pedis artery supplies the extensor digitorum brevis and the extensor hallucis brevis muscles.[26] Assessment of the dorsalis pedis pulse is useful when evaluating the integrity of the blood supply of the foot.

The Interosseous Compartment of the Foot

The dorsalis pedis artery enters the foot on its dorsal surface, producing the arcuate artery at the level of the bases of the metatarsal bones. The dorsal metatarsal arteries arise from the arcuate artery. The dorsal metatarsal arteries supply the second, third, and fourth dorsal interosseus muscles. The first dorsal interosseous muscle receives its blood supply from the distal continuation of dorsalis pedis artery. The plantar metatarsal arteries contribute to the vascular supply of the dorsal interossei, comprising the majority of the blood supply to the plantar interosseus muscles. These plantar metatarsal arteries are branches of the deep plantar arterial arch, an anastomotic arch formed by the lateral and deep plantar arteries. The deep plantar artery is a tributary of the dorsalis pedis artery that dives between the heads of the first dorsal interosseous muscle to join the deep plantar arch.[27]

The Lateral Compartment of the Sole of the Foot

The posterior tibial artery bifurcates distal to the tibial tunnel to form the lateral and medial plantar arteries. The lateral compartment of the sole receives its arterial supply from the lateral plantar artery. This compartment includes the abductor digiti minimi, the flexor digiti minimi, and the opponens digiti minimi muscles.[28]

The Central Compartment of the Sole of the Foot

The lateral plantar artery supplies the adductor hallucis and quadratus plantae muscles. Both the lateral and medial plantar arteries supply the lumbrical muscles. The medial plantar artery supplies the flexor digitorum brevis.[29]

The Medial Compartment of the Sole of the Foot

The medial compartment of the sole of the foot contains the abductor hallucis and the flexor hallucis brevis muscles. These are both supplied by the medial plantar artery.[29]

Embryology

In all mammals, the vascular supply of a limb develops from branches of the dorsal root of the umbilical artery, which forms a primitive axial artery, the ischiadic artery. This artery is present early in limb development. A second developmental artery arises later in development, traversing the pelvis and proximal thigh. This later artery will form the external iliac artery, the femoral artery, and the inferior epigastric artery.[30]

Physiologic Variants

There is a high level of variability in arterial branch points and the dominance of the circulation. This variability carries clinical significance. Some of the most predominant examples of physiologic variance include the inconsistent presence of the corona mortis, the incongruity in the arterial dominance of the proximal femoral artery, the trifurcation of the tibial artery to form the anterior tibial, the posterior tibial, and the fibular arteries, as well as the inconsistent presence of a superficial plantar arterial arch of the foot. There is a plethora of anatomic variations of each of the vessels. These variations differ in their clinical importance.[8][31][32][33][34]

Physiologic variation also occurs with varying ages. One example exists in the femoral head, where a significant blood supply exists within the ligamentum teres before adulthood; this supply degenerates with age, resulting in a predominate vascular supply from the medial femoral circumflex artery.[35]

Surgical Considerations

The iliac arteries and the arterial supply of the lower extremity are highly variable in their anatomy. Providing an individualized surgical treatment plan based on anatomical variations in surgical candidates is essential.[36]

Vascularized Bone Grafting

In instances of significant bone loss, bone grafting may be beneficial. The fibular bone graft relies on the supply from the peroneal (fibular) artery. This arterial supply conveys better viability than nonvascularized bone grafts and synthetic alternatives. Fibular bone grafts are the most common vascularized bone grafts, although the iliac crest, pubis, rib, radius, ulna, scapula, femur, humerus, and metatarsal grafts are also options.[37]

The Meniscal Blood Supply

The blood supply to the meniscus has three zones: red, pink, and white. These zones decrease in vascularity from the periphery to the interior. These differences are significant because many meniscal injuries occur in the interior zone with limited vascular supply and thus have limited ability to heal.[38]

Soft Tissue Flaps

Many variations of soft tissue flaps derive from the lower extremities. These have widespread relevance. For example, they are important in treating traumatic injuries and ulcers due to diabetes mellitus. Choosing the appropriate flap can have a dramatic impact on the outcome of the procedure.[7][39][40]

Clinical Significance

There are various important considerations for clinical practice concerning the arterial supply of the lower extremity. The following conditions are essential for the clinician to understand and incorporate into differential diagnoses when evaluating conditions affecting the pelvis and lower extremities.

The Corona Mortis

A meta-analysis of 21 studies demonstrated the presence of the corona mortis in nearly half of the hemipelves analyzed.[2] A corona mortis is a critical surgical consideration because its presence increases the probability of hemorrhage after pelvic injury. This anatomical constellation is important in planning for surgery in the retropubic region.

Legg-Calvé-Perthes Disease

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease highlights the tenuous blood supply to the femoral head and neck. This is an idiopathic disorder of the hip that results in avascular necrosis of the femoral head. This condition develops in children, typically between 5 and 8 years of age. The etiology remains a source of debate, although some researchers have identified genetic links and coagulopathies that may play a causal role in this condition. Children with this condition present with mild hip pain, a limp, and limited range of motion. When these symptoms present under six years of age, nonoperative management with physical therapy has equal outcomes compared to surgery. Patients six years and older seem to benefit from surgical intervention.[41]

Avascular Necrosis of the Femoral Head

In addition to Legg-Calvés-Perthes disease, there are many other causes of avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Etiologies include but are not limited to fracture, dislocation, coagulopathy, and sickle cell disease. However, the true etiology of the necrosis is often unknown. Risk factors such as smoking, hyperlipidemia, glucocorticoid usage, genetic predisposition, and autoimmune disease may be present. Surgical procedures that spare the head of the femur are generally preferred in younger patients, although arthroplasty is often necessary.[42]

Popliteal Artery Laceration (Knee Dislocation)

Knee dislocations are considered surgical emergencies because of the risk of neurovascular complications. Popliteal artery injury is reported to occur in 7.8 to 11.1% of patients with knee dislocations. Patients with vascular injuries also demonstrate an increased risk of other medical and surgical morbidities. There is significant variability in the reported rates of vascular injury in knee dislocations. Still, assessing patients for these complications remains important, especially in the context of high-energy trauma.[43]

Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD)

Peripheral arterial disease is a significant cause of morbidity and a predictor of mortality, especially in diabetic patients. The atherosclerotic process due to diabetes mellitus results in decreased ability to walk secondary to pain (intermittent claudication) and sensory deficits. Early medical and surgical intervention can help patients have better outcomes.[44]

Compartment Syndromes

The lower leg is the most prevalent site of compartment syndrome, especially in the context of tibial shaft fractures. This condition may occur in any of the four compartments of the lower leg; it most commonly occurs in the anterior compartment. Timely identification of the development of compartment syndrome is vital to prevent the destruction of tissues.[45]

The terminology of compartment syndrome is complex. Anterior compartment syndrome most commonly involves the distal leg and not the thigh. Despite the common use of anterior compartment syndrome, the terminology should be anterior compartment syndrome of the leg. A variant is the anterior crural compartment syndrome.

Physical findings of compartment syndrome may be remembered by the mnemonic of the five Ps: pulselessness, pain, pallor, paresthesias, and paralysis. Because the deep fibular nerve innervates the anterior compartment and supplies sensation only to the area between the big toe and the second toe, if other paresthesias are present, alternative diagnoses should be considered.

Manometric measurement of pressure within the anterior compartment can help to identify the presence of an anterior compartment syndrome.[46] Any intracompartmental pressure measurement over 30 mm Hg should be investigated, especially in trauma. The increased pressure can result in decreased tissue perfusion, often resulting in tissue necrosis.

Measuring the pulse of the dorsalis pedis artery can help identify the presence of an anterior crural compartment syndrome of the leg. However, this is not an infallible test; in 5% of patients, the dorsalis pedis artery is a branch of the fibular artery. Surgical treatment of anterior crural compartment syndrome consists of making vertical slits in the fascia that attaches to the anterior aspect of the tibia and fibula and should be performed within six hours of injury. After 36 hours, the loss of vascular function and resultant necrosis indicate that fasciotomy may not be helpful.[47]

Fractures of the tibia are the most common cause of acute anterior compartment syndrome. Other causes commonly involve soft tissue injury, including burns, crush injuries, thrombosis, bleeding disorders, intense athletic activities and injuries, and penetrating trauma.[47]

A milder variant of anterior compartment syndrome is chronic exertional anterior compartment syndrome.[48][49] This condition is commonly termed "shin splints," in which runners develop pain due to the presence of a tight anterior compartment. Mild cases can be treated with analgesics and rest. For more severe cases, surgical slits can be made in the fascia covering the anterior compartment to permit increased muscle swelling with exercise for patients who refuse to cease running.[48]

Talus Fracture

Approximately 80% of the talus is covered with articular cartilage and has no true muscle or tendinous attachment. It receives blood in a retrograde fashion. Blood supply is often disrupted with talar neck fractures, with a higher risk of delayed union and nonunion. Displaced talar neck fractures are better treated with surgical fixation to minimize these risks.

The Jones Fractures

Fractures of the base of the fifth metatarsal have a propensity towards nonunion secondary to avascular necrosis. This result occurs because there is an avascular watershed zone between the most proximal aspect of the base, known as the proximal tubercle, and the diaphysis.[24] The proximal fifth metatarsal can be divided into three zones: zone 1 is the proximal tubercle, zone 2 is the metaphyseal-diaphyseal junction, and zone 3 is the proximal metaphysis. Fractures are usually through the second zone. These fractures carry an increased risk of avascular necrosis. This necrosis is why it may be advisable to consider surgical fixation of these fractures; fixation decreases the rate of non-union.[50]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Branches of the Femoral Artery. This illustration shows the following structures: common femoral artery, deep femoral artery (femoral profunda), superficial femoral artery, perforating arteries, lateral circumflex artery, medial circumflex artery, descending branch of the lateral circumflex artery, anastomotica magna, and superior external and internal articular branches of the popliteal artery.

Contributed by Mikael Haggstrom (Public Domain)

References

Selçuk İ, Yassa M, Tatar İ, Huri E. Anatomic structure of the internal iliac artery and its educative dissection for peripartum and pelvic hemorrhage. Turkish journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2018 Jun:15(2):126-129. doi: 10.4274/tjod.23245. Epub 2018 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 29971190]

Sanna B, Henry BM, Vikse J, Skinningsrud B, Pękala JR, Walocha JA, Cirocchi R, Tomaszewski KA. The prevalence and morphology of the corona mortis (Crown of death): A meta-analysis with implications in abdominal wall and pelvic surgery. Injury. 2018 Feb:49(2):302-308. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2017.12.007. Epub 2017 Dec 9 [PubMed PMID: 29241998]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHARTY M. Blood supply of the femoral head. British medical journal. 1953 Dec 5:2(4848):1236-7 [PubMed PMID: 13106393]

Gautier E, Ganz K, Krügel N, Gill T, Ganz R. Anatomy of the medial femoral circumflex artery and its surgical implications. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 2000 Jul:82(5):679-83 [PubMed PMID: 10963165]

LAING PG. The blood supply of the femoral shaft; an anatomical study. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 1953 Aug:35-B(3):462-6 [PubMed PMID: 13084697]

Reddy AS, Frederick RW. Evaluation of the intraosseous and extraosseous blood supply to the distal femoral condyles. The American journal of sports medicine. 1998 May-Jun:26(3):415-9 [PubMed PMID: 9617405]

Mu LH, Yan YP, Luan J, Fan F, Li SK. [Anatomy study of superior and inferior gluteal artery perforator flap]. Zhonghua zheng xing wai ke za zhi = Zhonghua zhengxing waike zazhi = Chinese journal of plastic surgery. 2005 Jul:21(4):278-80 [PubMed PMID: 16248524]

Rajive AV, Pillay M. A Study of Variations in the Origin of Obturator Artery and its Clinical Significance. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2015 Aug:9(8):AC12-5. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/14453.6387. Epub 2015 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 26435935]

Schwartz JT Jr, Brumback RJ, Lakatos R, Poka A, Bathon GH, Burgess AR. Acute compartment syndrome of the thigh. A spectrum of injury. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1989 Mar:71(3):392-400 [PubMed PMID: 2925712]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTomaszewski KA, Henry BM, Vikse J, Pękala P, Roy J, Svensen M, Guay D, Hsieh WC, Loukas M, Walocha JA. Variations in the origin of the deep femoral artery: A meta-analysis. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2017 Jan:30(1):106-113. doi: 10.1002/ca.22691. Epub 2016 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 26780216]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLazaro LE, Cross MB, Lorich DG. Vascular anatomy of the patella: implications for total knee arthroplasty surgical approaches. The Knee. 2014 Jun:21(3):655-60. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2014.03.005. Epub 2014 Apr 2 [PubMed PMID: 24767718]

Menck J, Bertram C, Lierse W, Wolter D. [The arterial blood supply of the tibial and practical consequences]. Langenbecks Archiv fur Chirurgie. 1992:377(4):229-34 [PubMed PMID: 1508012]

Menck J, Sander A. [Periosteal and endosteal blood supply of the human fibula and its clinical importance]. Acta anatomica. 1992:145(4):400-5 [PubMed PMID: 10457784]

Basit H, Eovaldi BJ, Sharma S. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Peroneal Artery. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30855864]

Jang Y, Nguyen K, Rocky S. The Aberrant Anterior Tibial Artery and its Surgical Risk. American journal of orthopedics (Belle Mead, N.J.). 2018 Jul:47(7):. doi: 10.12788/ajo.2018.0057. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30075042]

Chmielewski P, Warchoł Ł, Gala-Błądzińska A, Mróz I, Walocha J, Malczak M, Jaworek J, Mizia E, Walocha E, Depukat P, Bachul P, Bereza T, Kurzydło W, Gach-Kuniewicz B, Mazur M, Tomaszewski K. Blood vessels of the shin - posterior tibial artery - anatomy - own studies and review of the literature. Folia medica Cracoviensia. 2016:56(3):5-9 [PubMed PMID: 28275266]

Mulfinger GL, Trueta J. The blood supply of the talus. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 1970 Feb:52(1):160-7 [PubMed PMID: 5436202]

Gupton M, Özdemir M, Terreberry RR. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Calcaneus. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30137829]

McKeon KE, McCormick JJ, Johnson JE, Klein SE. Intraosseous and extraosseous arterial anatomy of the adult navicular. Foot & ankle international. 2012 Oct:33(10):857-61. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2012.0857. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23050710]

Pountos I, Panteli M, Giannoudis PV. Cuboid Injuries. Indian journal of orthopaedics. 2018 May-Jun:52(3):297-303. doi: 10.4103/ortho.IJOrtho_610_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29887632]

Kraus JC, McKeon KE, Johnson JE, McCormick JJ, Klein SE. Intraosseous and extraosseous blood supply to the medial cuneiform: implications for dorsal opening wedge plantarflexion osteotomy. Foot & ankle international. 2014 Apr:35(4):394-400. doi: 10.1177/1071100713518505. Epub 2013 Dec 27 [PubMed PMID: 24375672]

Petersen WJ, Lankes JM, Paulsen F, Hassenpflug J. The arterial supply of the lesser metatarsal heads: a vascular injection study in human cadavers. Foot & ankle international. 2002 Jun:23(6):491-5 [PubMed PMID: 12095116]

McKeon KE, Johnson JE, McCormick JJ, Klein SE. The intraosseous and extraosseous vascular supply of the fifth metatarsal: implications for fifth metatarsal osteotomy. Foot & ankle international. 2013 Jan:34(1):117-23. doi: 10.1177/1071100712460227. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23386771]

Smith JW, Arnoczky SP, Hersh A. The intraosseous blood supply of the fifth metatarsal: implications for proximal fracture healing. Foot & ankle. 1992 Mar-Apr:13(3):143-52 [PubMed PMID: 1601342]

Hootnick DR, Packard DS Jr, Levinsohn EM, Factor DA. The anatomy of a human foot with missing toes and reduplication of the hallux. Journal of anatomy. 1991 Feb:174():1-17 [PubMed PMID: 2032928]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRobinson SA, Carlin R. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Foot Dorsalis Pedis Artery. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30570993]

Papon X, Brillu C, Fournier HD, Hentati N, Mercier P. Anatomic study of the deep plantar artery: potential by-pass receptor site. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 1998:20(4):263-6 [PubMed PMID: 9787393]

Wang T, Lin J, Song D, Zheng H, Hou C, Li L, Wu Z. Anatomical basis and design of the distally based lateral dorsal cutaneous neuro-lateral plantar venofasciocutaneous flap pedicled with the lateral plantar artery perforator of the fifth metatarsal bone: a cadaveric dissection. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2017 Feb:39(2):141-147. doi: 10.1007/s00276-016-1712-z. Epub 2016 Jun 13 [PubMed PMID: 27294973]

Rodriguez-Vegas M. Medialis pedis flap in the reconstruction of palmar skin defects of the digits: clarifying the anatomy of the medial plantar artery. Annals of plastic surgery. 2014 May:72(5):542-52. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e318268a901. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23486116]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSenior HD. An Interpretation of the Recorded Arterial Anomalies of the Human Leg and Foot. Journal of anatomy. 1919 Apr:53(Pt 2-3):130-71 [PubMed PMID: 17103859]

Hopkins JW, Warkentine F, Gracely E, Kim IK. The anatomic relationship between the common femoral artery and common femoral vein in frog leg position versus straight leg position in pediatric patients. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2009 Jul:16(7):579-84. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00430.x. Epub 2009 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 19519804]

Kawasaki Y, Kinose S, Kato K, Sakai T, Ichimura K. Anatomic characterization of the femoral nutrient artery: Application to fracture and surgery of the femur. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2020 May:33(4):479-487. doi: 10.1002/ca.23390. Epub 2019 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 31008535]

Tomaszewski KA, Popieluszko P, Graves MJ, Pękala PA, Henry BM, Roy J, Hsieh WC, Walocha JA. The evidence-based surgical anatomy of the popliteal artery and the variations in its branching patterns. Journal of vascular surgery. 2017 Feb:65(2):521-529.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.01.043. Epub 2016 Mar 16 [PubMed PMID: 26994952]

Zlotorowicz M, Czubak-Wrzosek M, Wrzosek P, Czubak J. The origin of the medial femoral circumflex artery, lateral femoral circumflex artery and obturator artery. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2018 May:40(5):515-520. doi: 10.1007/s00276-018-2012-6. Epub 2018 Apr 12 [PubMed PMID: 29651567]

Seeley MA, Georgiadis AG, Sankar WN. Hip Vascularity: A Review of the Anatomy and Clinical Implications. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2016 Aug:24(8):515-26. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00237. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27428883]

Rusu MC, Ilie AC, Brezean I. Human anatomic variations: common, external iliac, origin of the obturator, inferior epigastric and medial circumflex femoral arteries, and deep femoral artery course on the medial side of the femoral vessels. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2017 Nov:39(11):1285-1288. doi: 10.1007/s00276-017-1863-6. Epub 2017 Apr 27 [PubMed PMID: 28451829]

Bumbasirevic M, Stevanovic M, Bumbasirevic V, Lesic A, Atkinson HD. Free vascularised fibular grafts in orthopaedics. International orthopaedics. 2014 Jun:38(6):1277-82. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2281-6. Epub 2014 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 24562850]

Henning CE, Lynch MA, Clark JR. Vascularity for healing of meniscus repairs. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 1987:3(1):13-8 [PubMed PMID: 3566890]

Claes KE, Roche NA, Opsomer D, De Wolf EJ, Sommeling CE, Van Landuyt K. Free flaps for lower limb soft tissue reconstruction in children: Systematic review. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2019 May:72(5):711-728. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2019.02.028. Epub 2019 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 30898501]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRamanujam CL, Zgonis T. Use of Local Flaps for Soft-Tissue Closure in Diabetic Foot Wounds: A Systematic Review. Foot & ankle specialist. 2019 Jun:12(3):286-293. doi: 10.1177/1938640018803745. Epub 2018 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 30328715]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKim HK. Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2010 Nov:18(11):676-86 [PubMed PMID: 21041802]

Zalavras CG, Lieberman JR. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head: evaluation and treatment. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2014 Jul:22(7):455-64. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-22-07-455. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24966252]

Naziri Q, Beyer GA, Shah NV, Solow M, Hayden AJ, Nadarajah V, Ho D, Newman JM, Boylan MR, Basu NN, Zikria BA, Urban WP. Knee dislocation with popliteal artery disruption: A nationwide analysis from 2005 to 2013. Journal of orthopaedics. 2018 Sep:15(3):837-841. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2018.08.006. Epub 2018 Aug 16 [PubMed PMID: 30140130]

Mascarenhas JV, Albayati MA, Shearman CP, Jude EB. Peripheral arterial disease. Endocrinology and metabolism clinics of North America. 2014 Mar:43(1):149-66. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2013.09.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24582096]

Gordon WT, Talbot M, Shero JC, Osier CJ, Johnson AE, Balsamo LH, Stockinger ZT. Acute Extremity Compartment Syndrome and the Role of Fasciotomy in Extremity War Wounds. Military medicine. 2018 Sep 1:183(suppl_2):108-111. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usy084. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30189076]

Vogels S, Ritchie ED, de Vries D, Kleinrensink GJ, Verhofstad MHJ, Hoencamp R. Applicability of devices available for the measurement of intracompartmental pressures: a cadaver study. Journal of experimental orthopaedics. 2022 Sep 27:9(1):98. doi: 10.1186/s40634-022-00529-0. Epub 2022 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 36166161]

Torlincasi AM, Lopez RA, Waseem M. Acute Compartment Syndrome. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28846257]

Wilder RP, Magrum E. Exertional compartment syndrome. Clinics in sports medicine. 2010 Jul:29(3):429-35. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2010.03.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20610031]

Palese A, Gonella S, Grassetti L, Mansutti I, Brugnolli A, Saiani L, Terzoni S, Zannini L, Destrebecq A, Dimonte V, SVIAT TEAM. Multi-level analysis of national nursing students' disclosure of patient safety concerns. Medical education. 2018 Nov:52(11):1156-1166. doi: 10.1111/medu.13716. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30345687]

Portland G, Kelikian A, Kodros S. Acute surgical management of Jones' fractures. Foot & ankle international. 2003 Nov:24(11):829-33 [PubMed PMID: 14655886]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence