Introduction

Lichen simplex chronicus is defined as a common form of chronic neurodermatitis that presents as dry, patchy areas of skin that are scaly and thick. The hypertrophic epidermis generally seen is typically the result of habitual scratching or rubbing of a specific area of the skin. The root of the disorder may be both a primary symptom, reflective of perhaps a psychological component or secondary to other cutaneous issues such as eczema or psoriasis. The development of such plaques is the result of the pruritic dermatoses that typically result from the psychological stressors. [1][2][3]It typically affects specific areas of the body as described below. Although lichen simplex chronicus is most often a non-life-threatening skin disorder, the frequent itching can lead to infection, changes to how keratinocytes divide and grow, and subsequent, although rarely observed, malignant transformation of the epithelial tissues affected.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Several studies have linked lichen simplex chronicus to emotional factors, which often result in repeated and cyclic itching as a means to quell emotional disturbances or as a result of an intense need to scratch an area that studies show are subsequent to an emotional disturbance. The plaques form as a result of constant and repeated scratching of specific areas.[4][5][6] The most common areas are on self-accessible areas of the body such as the scalp, head, neck, hands, arms, and genitals.

The emotional stress causing the irritation and the urge to scratch at the skin is often cyclic, with the resultant plaques causing more stress and chronic itching, pigmentation changes of the affected skin, and a possible spread to larger areas. This is a largely pruritic disorder, though it can result from disorders of the skin barrier it also can be secondary to other dermatoses including xerosis, psoriasis, atopy, or others.

Epidemiology

Lichen simplex chronicus has been estimated to occur in approximately 12% of the population. The highest prevalence is typically from middle to late adulthood and often peaks at 30 to 50 years of age, likely due to the significant increase in stress at this point in one’s life. The disorder is more prevalent in females than in males at a ratio of 2:1.

Pathophysiology

Lichen simplex chronicus located in areas of the skin that are accessible to scratching. Localized areas of the skin itch spontaneously, leading to an itch and scratch cycle. Itching provokes the rubbing that produces lesions, but its underlying pathophysiology is not known. Skin with atopic dermatitis or atopic diathesis is most likely to develop lichenification. A potential relationship may exist between central and peripheral neural tissue and inflammatory mediators in the perception of itch and developing changes seen in lichen simplex chronicus. Anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder or other emotional stressors may lead to scratching. One study of lichen simplex chronicus with P-phenylenediamine (PPD)–containing hair dye showed improvement in symptoms when PPD exposure was stopped which gave a basis for sensitization and contact dermatitis leading to lichen simplex chronicus.

Histopathology

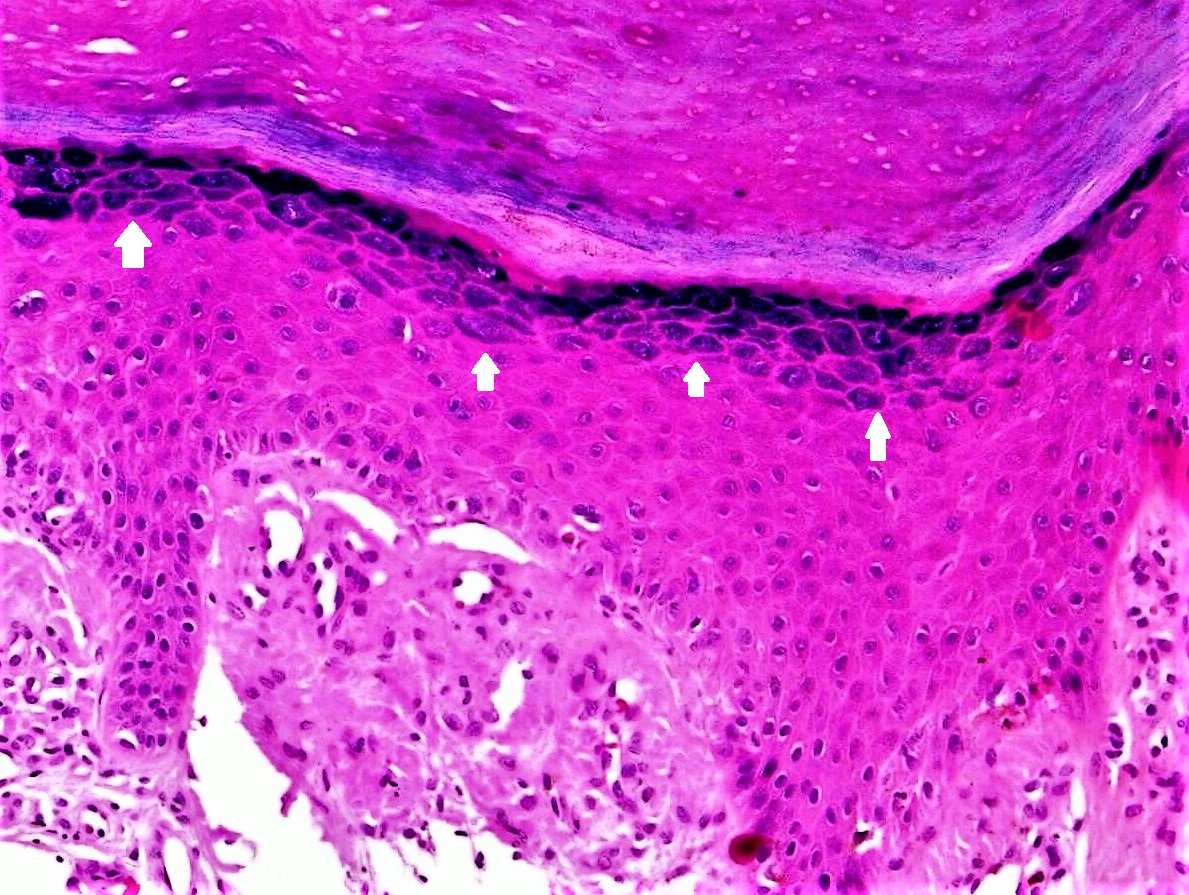

Pathology of lichen simplex chronicus shows a hyperkeratotic plaque with foci of parakeratosis, prominent granular cell layer, elongated and irregularly thickened epidermal rete, acanthosis, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, papillary dermal fibrosis, mild spongiosis, and perivascular as well as interstitial inflammation with histiocytes, lymphocytes, and occasional eosinophils in the superficial dermis. Electron microscopy shows collagen fibers attached to and above the lamina basalis.

History and Physical

Lichen simplex chronicus can present as single or multiple lesions, and while they may occur anywhere, they almost always appear in easy to reach areas including the head, neck, arms, scalp, and genitals. The most common symptom is itching. Plaques and thickened, potentially discolored lesions may develop as a result of repeated scratching of the affected area. The color of such lesions can vary with varying degrees of erythema. The overall color of the lesions ranges between different shades of yellow or a deep reddish brown, which is most commonly present in the center portion of the lesion. However, with the respective age of the lesion, this color may transform into a leucodermic center with a darker zone surrounding the lesion. These plaques can vary in size between 3 by 6-centimeter to 6 by 10-centimeter areas.

Evaluation

Diagnosis of lichen simplex chronicus includes a physical exam, a complete medical history, dermoscopy, and self-reported symptoms. Patch testing can eliminate possible allergic reactions due to contact dermatitis as a cause of the lesions. If the lichen simplex chronicus is in the genital area, then a potassium hydroxide examination and fungal cultures are helpful to exclude tinea cruris or candidiasis. Skin biopsies can be performed to exclude disorders such as psoriasis or mycosis fungoides. Blood tests may be performed as well; for example, elevated serum immunoglobulin E levels support the diagnosis of an underlying atopic diathesis.[7][8]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of lichen simplex chronicus may include the following: occlusion of the area; topical anti-inflammatory therapies such as corticosteroids (high-potency versions may be used for 3 weeks at a time for thicker plaques/lesions); topical emollients; antibiotics if infection is highly likely or present, especially if immunosuppressant drug therapy is being utilized; and antihistamines can be used to prevent exacerbation by allergic mediators. [9][10][11]Doxepin and capsaicin also can be used. A small size controlled clinical trial suggest that a topical mix of aspirin/dichloromethane may be effective for patients who are not responding to other topical agents. Other studies cite the efficacy of immunomodulators tacrolimus and pimecrolimus for those unresponsive patients as well. Phototherapy with UVA and/or UVB exposure therapy, as well as photochemotherapy, may be used for severe cases, except in case of genital involvement. Psychological treatment, such as psychotherapy as well as respective drug therapies, such as anti-anxiety medications, also can assist due to the etiological nature of the disorder. Recent studies suggest that for those patients for whom conventional treatments have failed, local injections of botulinum toxin may be useful. Surgical measures may include cryosurgery, and for those cases that persist in spite of all other treatment options, surgical excision of small, localized lesions may be justified.(B2)

Differential Diagnosis

The following conditions should be excluded: psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, lichen planus, contact dermatitis, mycosis fungoides, fungal infections, and squamous cell carcinoma.

Prognosis

Lichen simplex chronicus usually improves with treatment, but some cases may become persistent, especially when on the genitals.

Pearls and Other Issues

In recent studies, patients with lichen simplex chronicus exhibited the following personality traits: poor social skills, a lack of flexibility, a greater tendency to pain-avoidance, greater dependency on other peoples' desires, and a more dutiful nature as compared to control groups. Some cases of malignant transformation of lichen simplex chronicus lesions into squamous cell carcinoma or verrucous carcinoma. This may be due to the fact that repeated scratching and rubbing of the lesions contribute to excess inflammatory mediators, which can, in turn, alter the manner in which keratinocytes grow and develop and, in such a chronic case, may lead, to the transformation of these cells into malignancy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

When healthcare providers, including the nurse practitioner, encounter patients with chronically dry and itchy skin lesions, they should refer these patients to a dermatologist. The differential is broad and the diagnosis of chronic lichen simplex requires elimination of many disorders. Besides symptomatic treatment of the skin lesions, many of these patients may benefit from psychological assesment. Some of these patients may benefit from antidepressants.

The outcomes of the chronic lichen simplex depend on the primary cause; if the mental health disorder is not managed, the disorder is chronic and can lead to a poor quality of life.[12]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Figure 1. Histological demonstration of keratohyalin granules in a biopsy specimen obtained from the skin and stained with hematoxylin & eosin. The granules (highlighted by white arrows) appear blue owing to their basophilic nature. This section was taken from a lesion of lichen simplex chronicus, and therefore displays epidermal changes including hypergranulosis apart from hyperkeratosis (thickened stratum corneum), and irregular acanthosis (thickening of stratum spinosum). [hematoxylin & eosin, 400X] Contributed by Sidharth Sonthalia, MD, DNB, MNAMS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Aboobacker S, Harris BW, Limaiem F. Lichenification. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30726017]

Borghi A, Virgili A, Corazza M. Dermoscopy of Inflammatory Genital Diseases: Practical Insights. Dermatologic clinics. 2018 Oct:36(4):451-461. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2018.05.013. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30201154]

Boozalis E, Grossberg AL, Püttgen KB, Cohen BA, Kwatra SG. Itching at night: A review on reducing nocturnal pruritus in children. Pediatric dermatology. 2018 Sep:35(5):560-565. doi: 10.1111/pde.13562. Epub 2018 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 29943835]

Savas JA, Pichardo RO. Female Genital Itch. Dermatologic clinics. 2018 Jul:36(3):225-243. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2018.02.006. Epub 2018 Apr 26 [PubMed PMID: 29929595]

Muylaert BPB, Borges MT, Michalany AO, Scuotto CRC. Lichen simplex chronicus on the scalp: exuberant clinical, dermoscopic, and histopathological findings. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2018 Jan-Feb:93(1):108-110. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20186493. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29641708]

Voicu C, Tebeica T, Zanardelli M, Mangarov H, Lotti T, Wollina U, Lotti J, França K, Batashki A, Tchernev G. Lichen Simplex Chronicus as an Essential Part of the Dermatologic Masquerade. Open access Macedonian journal of medical sciences. 2017 Jul 25:5(4):556-557. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2017.133. Epub 2017 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 28785363]

Sand FL, Thomsen SF. Skin diseases of the vulva: eczematous diseases and contact urticaria. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology : the journal of the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2018 Apr:38(3):295-300. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2017.1329283. Epub 2017 Aug 7 [PubMed PMID: 28780897]

Chibnall R. Vulvar Pruritus and Lichen Simplex Chronicus. Obstetrics and gynecology clinics of North America. 2017 Sep:44(3):379-388. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2017.04.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28778638]

Fruchter R, Melnick L, Pomeranz MK. Lichenoid vulvar disease: A review. International journal of women's dermatology. 2017 Mar:3(1):58-64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.02.017. Epub 2017 Mar 27 [PubMed PMID: 28492056]

Day T, Bohl TG, Scurry J. Perianal lichen dermatoses: A review of 60 cases. The Australasian journal of dermatology. 2016 Aug:57(3):210-5. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12308. Epub 2015 Mar 6 [PubMed PMID: 25752318]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBoyd K, Shea SM, Patterson JW. The role of capsaicin in dermatology. Progress in drug research. Fortschritte der Arzneimittelforschung. Progres des recherches pharmaceutiques. 2014:68():293-306 [PubMed PMID: 24941674]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLiao YH, Lin CC, Tsai PP, Shen WC, Sung FC, Kao CH. Increased risk of lichen simplex chronicus in people with anxiety disorder: a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. The British journal of dermatology. 2014 Apr:170(4):890-4. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12811. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24372057]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence