Introduction

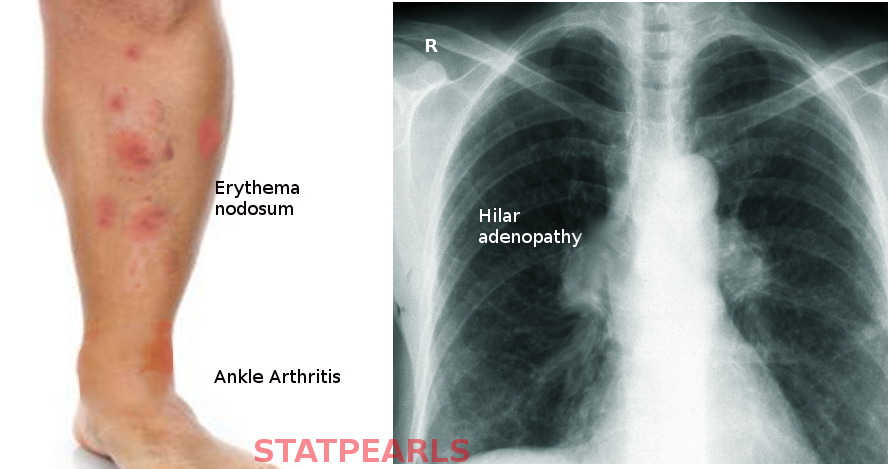

Lofgren syndrome is a clinically distinct phenotype of sarcoidosis, first described in 1946 by Swedish pulmonologist Sven Lofgren. Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disorder of unknown etiology that commonly involves the lungs with the second most commonly affected organ being the skin.[1] Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis are seen in up to 33% of patients and may be the first clinical sign of the disease.[2] In contrast to the often-insidious onset, slow disease progression and chronic disease course typical of sarcoidosis, Lofgren’s syndrome presents acutely. It typically presents in younger patients with acute onset erythema nodosum (EN), bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, fever, and migratory polyarthritis, and without granulomatous skin involvement. Lofgren’s syndrome portends a favorable prognosis.[3][4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Etiology and pathophysiology of cutaneous sarcoidosis are poorly understood and attributable to both genetic and environmental factors. Though acute sarcoidosis is not infectious, there is some thought that selected cases may be due to abnormal host reaction to exposure to one or more infective agents, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Propionibacterium or environmental exposures, such as beryllium, dust, or other occupational agents.[5][6][7]

Epidemiology

Sarcoidosis affects patients of all ages and races. The incidence and clinical presentation of sarcoidosis differ depending on gender, ethnicity, geographic location, and genetic background. In the United States, women are affected more often than men with an overall African American predominance.[8] Worldwide, the incidence of sarcoidosis is highest in Scandinavians (Sweden and the United Kingdon) and lowest in Spain and Japan.[8]

Lofgren syndrome consistently appears to be more common in females. It occurs most commonly in European Caucasians, especially patients with Scandinavian descent. Young to middle age adults are more likely to present with this disease with a median age of 37 years old. Specific manifestations of the components of Lofgren syndrome differ based on gender, whereas erythema nodosum is found predominantly in women and arthropathy/arthritis is seen more commonly in men. It classically occurs in the spring months.

Pathophysiology

In general, sarcoidosis is thought to be a polygenic disorder. The impact of HLA alleles on the pathogenesis of sarcoidosis varies significantly, depending upon disease subtype and racial group. In the case of Lofgren syndrome, HLA-B8/DR3 has a strong association with the disease and also with overall disease resolution.[9]

Despite a rigorous investigation, research has not unveiled a cause or proven pathophysiologic mechanism. The hypothesis is that hosts may have a genetic predisposition but still require exposure to a specific antigen whether it be exogenous or endogenous. This trigger then activates macrophages and ultimately leads to an exaggerated cellular immune response leading to granuloma formation. The pathogenesis is very complex and not yet well understood. At the core of the process, T cells play a dominant role in this immune reaction. Studies have shown that granulomas and bronchioloalveolar lavage samples from patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis shown mixed infiltrate with prominent lymphocytosis.[10]

The majority of lymphocytes within sarcoidal granulomas are CD4+T helper 1 (Th1) lymphocytes, contributing to an overall elevated CD4/CD8 ratio. CD4+T cells secrete interleukin (IL)-2, IL-12, IL-18, and interferon (IFN)-gamma, which in combination with the release of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha by macrophages and some CD8+T cells, leads to persistent Th1 activity, persistent IFN-gamma elevation and macrophage accumulation within the tissue. Compartmentalization of granuloma-forming CD4+ T lymphocytes and monocytes/macrophages within peripheral tissues leads to systemic lymphopenia and decreased systemic CD4/CD8 ratio.

Despite this understanding, the evidence is emerging noting bronchioloalveolar lavage samples may have CD4 to CD8 ratio is of less importance because it can increase, be normal, and even decrease.[10] Studies have also noted patients with active sarcoidosis with elevated Th17 to Treg ratio in the peripheral blood and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.[11]

Histopathology

Lofgren syndrome typically does not require a histologic diagnosis. On pathology, it similar to other forms of sarcoidosis in that it characteristically presents with non-caseating epithelioid granulomas, usually with a sparse or absent surrounding lymphocytic inflammation, also known as “naked” granulomas, seen on biopsy.[12]

History and Physical

Lofgren syndrome is a constellation of the following findings: erythema nodosum, bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, fever, and migratory polyarthritis.[3] It occasionally also presents with uveitis.[3]

The arthritis of Lofgren syndrome occurs more often in men, and with periarticular inflammation involving soft tissue and tenosynovitis rather than true arthritis. It typically involves ankles symmetrically but can also involve knees, wrists, and elbow.

Erythema nodosum presents as painful, bright red, subcutaneous nodules that are typically symmetric on the anterior shins, in contrast to macular/papular sarcoidosis which has a predilection for sites of repetitive trauma. These lesions along with the fever typically remit spontaneously within 6 weeks and may resolve with post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation but without scarring or atrophy. Resolution of lymphadenopathy may delay, taking up to one year, but does resolve completely in 90% of cases.

Evaluation

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is complex with no definitive test exists. It requires clinical-radiographic correlation, exclusion of alternative disease that can induce granuloma formation, such as tuberculosis, and histologic detection of noncaseating granulomas. There are several specific clinical situations where a presumptive diagnosis can be made based on clinic radiographic findings alone, and biopsy is not considered necessary.[13][14] Bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, migratory polyarthralgia, erythema nodosum, and fevers of Lofgren syndrome is one such example.[15]

Chest radiography is still necessary to make this diagnosis though may see a variety of alternative pathology other than classic bilateral hilar adenopathy, including unilateral hilar adenopathy or right paratracheal lymphadenopathy with or without pulmonary involvement.

Should disease deviate from the classic course or fail to resolve within expected time definitive histologic diagnosis may be necessary. The first step in diagnosis should be to determine the most appropriate site for biopsy. Of note, lesions of erythema nodosum will not show sarcoidal granulomas and are therefore not useful biopsy sites to establishing the diagnosis. A comprehensive physical examination should be performed with extra caution taken to examine periorificial sites, including parotid glands, lacrimal glands, and conjunctiva, extremities, sites of previous trauma or tattoos, and full lymph node assessment. Without an easily accessible superficial biopsy site, patients may require a more invasive biopsy method. Alternatively, minimally invasive methods have emerged including flexible bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), endobronchial biopsy, and transbronchial biopsy to assist in the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Several studies have noted the increased amount of activated CD4+ Th1 cells, decreased CD8+ T cells, and an increase in IgG-secreting plasma cells. Consequently, a CD4/CD8 ratio greater than 3.5 has been shown to have a 94% specificity for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis.

Other lab tests are not typically required and remain quite non-specific. Findings may include systemic lymphopenia, elevated levels of calcium, alkaline phosphatase, C-reactive protein (CRP), angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), or gamma globulin (polyclonal). Tuberculin skin test or measurement of IFN-gamma in undiluted plasma should be performed in all patients to exclude the diagnosis of tuberculosis which can mimic both erythema nodosum and sarcoidosis.[16] There are reports of thyroid dysfunction in association with cutaneous disease, consider the evaluation of thyroid function following definitive diagnosis.[17]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of Lofgren syndrome is typically supportive with spontaneous resolution occurring over 1 to 2 years. Constitutional symptoms and arthralgias are treatable with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug or colchicine. In rare, severe cases may warrant corticosteroids use which can usually be tapered quickly over a few weeks to months.[18]

Differential Diagnosis

The reaction pattern of fever, arthralgia, and lesions of erythema nodosum, though suggestive are not specific for sarcoidosis. Reactions may be idiopathic or caused by several other triggers including:

- Medication-induced causes of penicillin, sulfa drugs, oral contraceptives, immunizations

- Infections such as Streptococcus, enteric bacteria, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis

- Other systemic inflammatory diseases like inflammatory bowel disease, lupus, Behcet disease

- Pregnancy

Approximately 10% to 22% of cases of erythema nodosum are attributable to sarcoidosis. A thorough medical history can help distinguish between many of the above causes of erythema nodosum. Tuberculosis should be ruled out with either Tuberculin skin test or QuantiFERON gold. Combination of classic radiographic pulmonary findings of bilateral hilar adenopathy can assist in confirming the diagnosis of Lofgren syndrome. As discussed above, if syndrome does not follow the classic timeline alternative diagnosis should be considered, and histologic confirmation of disease is necessary.

Prognosis

Lofgren syndrome portends an excellent prognosis is associated with a greater than 90% chance of spontaneous remission within 2 years.

Pearls and Other Issues

Lofgren syndrome is a specific acute clinical presentation of systemic sarcoidosis, consisting of a classic triad of fever, erythema nodosum, and bilateral hilar adenopathy; however, this characteristic triad is not always present and has also been associated with migratory polyarthritis, especially involving ankles in men. Must have a chest radiograph to confirm hilar adenopathy. Otherwise, no specific confirmatory tests are necessary. There is significant overlap among other known etiologies of erythema nodosum which can also contribute to systemic granuloma formation. Should presentation deviate from classic findings listed above further workup and, histopathologic correlation is required. Ultimately, sarcoidosis remains a diagnosis of exclusion.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disorder with no known etiology. The diagnosis and management of sarcoidosis, especially Lofgren syndrome, requires a multi-specialty and an interprofessional approach that including dermatology, pulmonology, radiology, and ophthalmology, with assistance from specialty-trained nursing staff and pharmacists who can assist in patient education and coordinating symptomatic management. This healthcare team approach can lead to better patient outcomes resulting from the delivery of optimal care. [Level V]

Media

References

Siltzbach LE, James DG, Neville E, Turiaf J, Battesti JP, Sharma OP, Hosoda Y, Mikami R, Odaka M. Course and prognosis of sarcoidosis around the world. The American journal of medicine. 1974 Dec:57(6):847-52 [PubMed PMID: 4432869]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWanat KA, Rosenbach M. Cutaneous Sarcoidosis. Clinics in chest medicine. 2015 Dec:36(4):685-702. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2015.08.010. Epub 2015 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 26593142]

Ponhold W. [The Löfgren syndrome: acute sarcoidosis (author's transl)]. Rontgen-Blatter; Zeitschrift fur Rontgen-Technik und medizinisch-wissenschaftliche Photographie. 1977 Jun:30(6):325-7 [PubMed PMID: 897518]

JAMES DG, THOMSON AD, WILLCOX A. Erythema nodosum as a manifestation of sarcoidosis. Lancet (London, England). 1956 Aug 4:271(6936):218-21 [PubMed PMID: 13347112]

Ferrara G, Valentini D, Rao M, Wahlström J, Grunewald J, Larsson LO, Brighenti S, Dodoo E, Zumla A, Maeurer M. Humoral immune profiling of mycobacterial antigen recognition in sarcoidosis and Löfgren's syndrome using high-content peptide microarrays. International journal of infectious diseases : IJID : official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases. 2017 Mar:56():167-175. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2017.01.021. Epub 2017 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 28159576]

Ishige I, Eishi Y, Takemura T, Kobayashi I, Nakata K, Tanaka I, Nagaoka S, Iwai K, Watanabe K, Takizawa T, Koike M. Propionibacterium acnes is the most common bacterium commensal in peripheral lung tissue and mediastinal lymph nodes from subjects without sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis, vasculitis, and diffuse lung diseases : official journal of WASOG. 2005 Mar:22(1):33-42 [PubMed PMID: 15881278]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNewman LS, Rose CS, Bresnitz EA, Rossman MD, Barnard J, Frederick M, Terrin ML, Weinberger SE, Moller DR, McLennan G, Hunninghake G, DePalo L, Baughman RP, Iannuzzi MC, Judson MA, Knatterud GL, Thompson BW, Teirstein AS, Yeager H Jr, Johns CJ, Rabin DL, Rybicki BA, Cherniack R, ACCESS Research Group. A case control etiologic study of sarcoidosis: environmental and occupational risk factors. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2004 Dec 15:170(12):1324-30 [PubMed PMID: 15347561]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNewman LS, Rose CS, Maier LA. Sarcoidosis. The New England journal of medicine. 1997 Apr 24:336(17):1224-34 [PubMed PMID: 9110911]

Spagnolo P, Sato H, Grunewald J, Brynedal B, Hillert J, Mañá J, Wells AU, Eklund A, Welsh KI, du Bois RM. A common haplotype of the C-C chemokine receptor 2 gene and HLA-DRB1*0301 are independent genetic risk factors for Löfgren's syndrome. Journal of internal medicine. 2008 Nov:264(5):433-41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.01984.x. Epub 2008 May 29 [PubMed PMID: 18513341]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDrent M, Mansour K, Linssen C. Bronchoalveolar lavage in sarcoidosis. Seminars in respiratory and critical care medicine. 2007 Oct:28(5):486-95 [PubMed PMID: 17975776]

Mortaz E, Rezayat F, Amani D, Kiani A, Garssen J, Adcock IM, Velayati A. The Roles of T Helper 1, T Helper 17 and Regulatory T Cells in the Pathogenesis of Sarcoidosis. Iranian journal of allergy, asthma, and immunology. 2016 Aug:15(4):334-339 [PubMed PMID: 27921415]

Cardoso JC, Cravo M, Reis JP, Tellechea O. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: a histopathological study. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2009 Jun:23(6):678-82. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03153.x. Epub 2009 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 19298487]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence. Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1999 Aug:160(2):736-55 [PubMed PMID: 10430755]

Mañá J, Gómez-Vaquero C, Montero A, Salazar A, Marcoval J, Valverde J, Manresa F, Pujol R. Löfgren's syndrome revisited: a study of 186 patients. The American journal of medicine. 1999 Sep:107(3):240-5 [PubMed PMID: 10492317]

MAYOCK RL, BERTRAND P, MORRISON CE, SCOTT JH. MANIFESTATIONS OF SARCOIDOSIS. ANALYSIS OF 145 PATIENTS, WITH A REVIEW OF NINE SERIES SELECTED FROM THE LITERATURE. The American journal of medicine. 1963 Jul:35():67-89 [PubMed PMID: 14046006]

LOFGREN S, LUNDBACK H. The bilateral hilar lymphoma syndrome; a study of the relation to tuberculosis and sarcoidosis in 212 cases. Acta medica Scandinavica. 1952 Mar 19:142(4):265-73 [PubMed PMID: 14932794]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAnolik RB, Schaffer A, Kim EJ, Rosenbach M. Thyroid dysfunction and cutaneous sarcoidosis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2012 Jan:66(1):167-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.04.026. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22177644]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZisman DA, Shorr AF, Lynch JP 3rd. Sarcoidosis involving the musculoskeletal system. Seminars in respiratory and critical care medicine. 2002 Dec:23(6):555-70 [PubMed PMID: 16088651]