Introduction

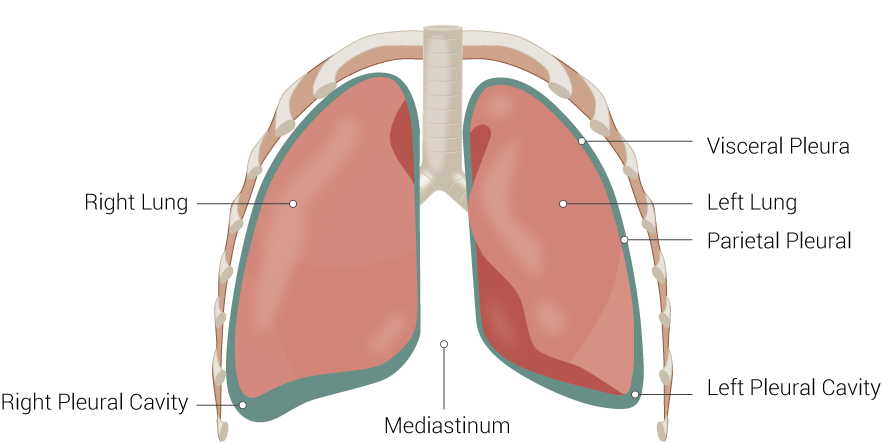

A pleura is a serous membrane that folds back on itself to form a two-layered membranous pleural sac. The outer layer is called the parietal pleura and attaches to the chest wall. The inner layer is called the visceral pleura and covers the lungs, blood vessels, nerves, and bronchi. There is no anatomical connection between the right and left pleural cavities.[1] See Image. Lung Anatomy. With the addition of pleural fluid, the lung pleura allows for easy movement of the lungs and inflation during breathing.

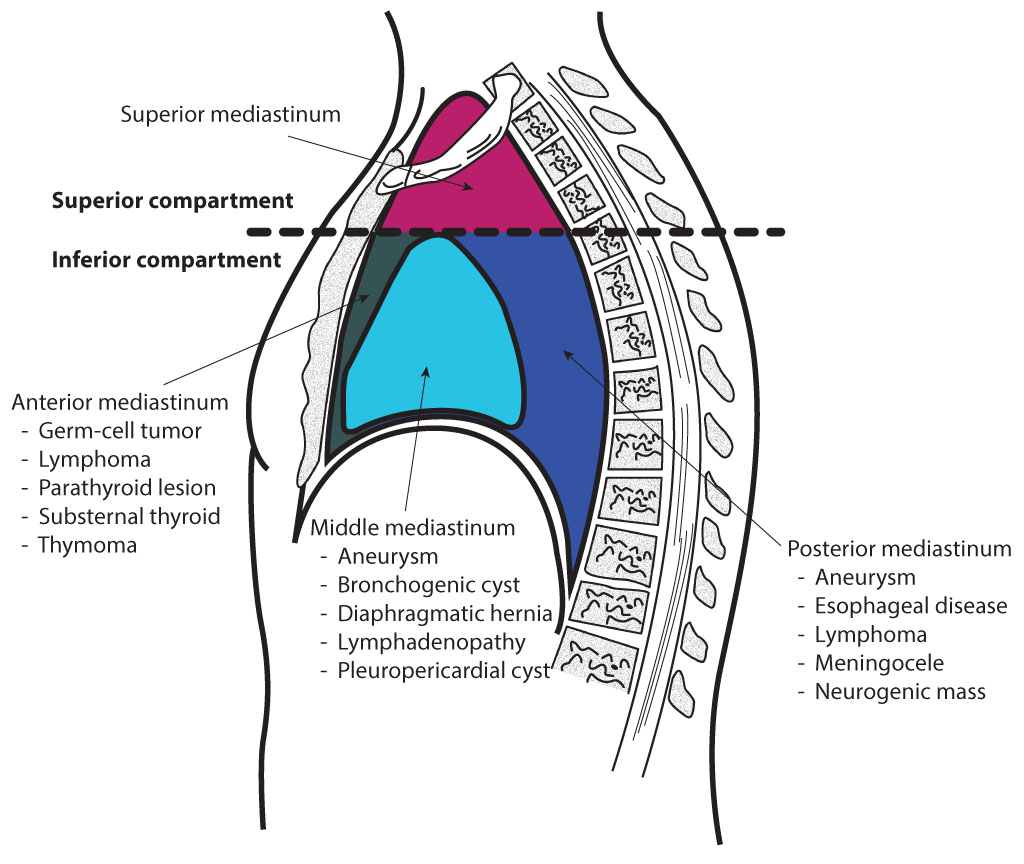

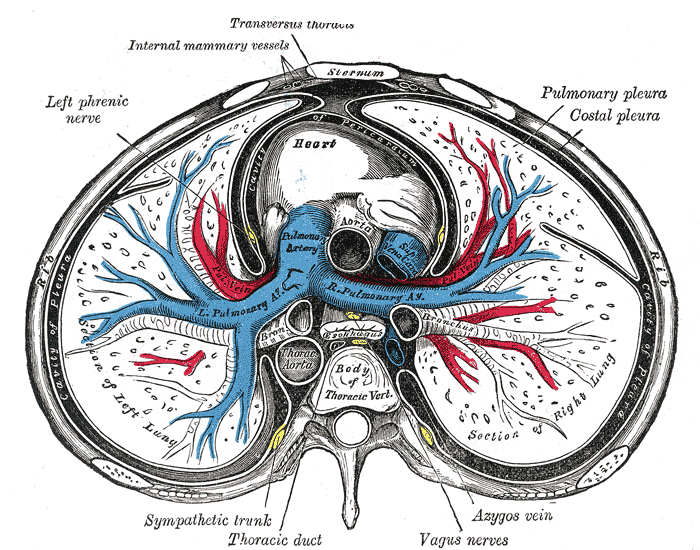

The mediastinum is a central compartment in the thoracic cavity between the pleural sacs of the lungs (see Image. The Mediastinum, Transverse Section of the Thorax). It is divided into two major parts, the superior and inferior portions. The inferior portion is then further divided into the anterior, middle, and posterior portions. Each region of the mediastinum contains specific groups of structures.[2] See Image. Mediastinal Divisions.

- Superior mediastinum: Organs: thymus, trachea, esophagus; Arteries: aortic arch, brachiocephalic trunk, left common carotid artery, left subclavian artery; Veins and lymphatics: superior vena cava, brachiocephalic vein, thoracic duct; Nerves: vagus nerve, left recurrent laryngeal nerve, cardiac nerve, phrenic nerve.

- Anterior mediastinum: Organs: thymus; Arteries: small arterial branches; Veins and lymphatics: small branches; Nerves: none.

- Middle mediastinum: Organs: heart, pericardium; Arteries: ascending aorta, pulmonary trunk, pericardiacophrenic arteries; Veins and lymphatics: superior vena cava, azygos vein, pulmonary vein, pericardiacophrenic vein; Nerve: phrenic

- Posterior mediastinum: Organs: esophagus; Arteries: thoracic aorta; Veins and lymphatics: Azygos vein, hemiazygos vein, thoracic duct; Nerve: the vagus nerve.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The pleural cavity is a space between the visceral and parietal pleura. The space contains a tiny amount of serous fluid, which has two key functions.

The serous fluid continuously lubricates the pleural surface and makes it easy for them to slide over each other during lung inflation and deflation. The serous fluid also generates surface tension, which pulls the visceral and parietal pleura adjacent to each other. This function will allow the thoracic cavity to expand during inspiration.

NB; when air enters the pleural space, the surface tension will disappear, and the resulting condition is known as a pneumothorax.

Pleural Recesses

Located posteriorly and anteriorly are spaces where the pleural cavity is not totally filled by the lung parenchyma. This space is known as the recess - an area where the adjacent surfaces of the parietal pleura come into contact. The two recesses in the pleural cavity include the following:

- The costomediastinal recess is one of these two spaces, which is found between the mediastinal and costal pleura. The space is located just posterior to the sternum.

- The costodiaphragmatic recess is the other, which is between the diaphragmatic and costal pleura.

The reason these recesses are important is that they provide a space for fluid to accumulate. Pleural effusions usually collect in the costodiaphragmatic recess.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The visceral pleura receives its blood supply from the bronchial circulation, while the parietal pleura receives its blood supply from the intercostal arteries.[3][4]

Nerves

The costal and cervical portions of the parietal pleura are innervated by the intercostal nerve, and the diaphragmatic portion is supplied by the phrenic nerve. The parietal pleura is the only portion of the pleura that can sense pain. The visceral pleura receives its nerve supply via the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and lacks sensory innervation.[5]

Surgical Considerations

Pneumothorax is a common clinical event, and it occurs when the pleural space is violated.[6][7] The patient can present with a variety of symptoms depending on the size of the pneumothorax. With a small pneumothorax, the patient may be asymptomatic. But if the pneumothorax is large, the following symptoms will be present:

- Chest pain

- Dyspnea

- Asymmetrical chest expansion

Percussion and auscultation will reveal a hyper-resonant chest with no breath sounds.

The two types of pneumothorax include:

Spontaneous: These pneumothoraces occur without any traumatic event. They are most common in young males who smoke. The most common cause of a spontaneous pneumothorax is the presence of small blebs on the superior surface of the upper lobes.[6]

Traumatic: Traumatic pneumothorax is very common and may occur as a result of a central line insertion, penetrating chest trauma, or rib fracture.[7]

The treatment of a pneumothorax again depends on the size and presence of symptoms. Most asymptomatic cases can be observed if the patient is reliable and agrees to follow up. Repeat chest X-rays are required to ensure that the pneumothorax is resolving. For patients with large and symptomatic pneumothorax, insertion of a chest tube is the most straightforward treatment. Unlike the past when large-sized chest tubes were inserted, today, several kits are available with small size 8-12 French tubes which can be inserted without causing too much pain.[8]

Clinical Significance

Normally, there is a small amount of pleural fluid found in the pleural cavity. When there is a pathological collection of pleural fluid, it is called a pleural effusion. Pleural effusion is classified as either exudative or transudative and can be caused by multiple mechanisms, including lymphatic obstruction, increased capillary permeability, decreased plasma colloid pressure, increased capillary, venous pressure, and increased negative intrapleural pressure.

The mediastinum is commonly a site for tumors, and specific regions of the mediastinum are prone to certain tumors. Pneumomediastinum can also develop when air is introduced into the mediastinum, most commonly seen in ruptures of the esophagus. A widened mediastinum is a worrisome clinical sign for possible aortic aneurysm or rupture.[9]

The mediastinum is also very important with respect to lung cancer—all lung cancers when in advanced stages, involve the mediastinal lymph nodes. The treatment for a patient with lung cancer without mediastinal lymph node involvement is surgery, and it has a high cure rate. However, surgery alone is not curative once the mediastinal nodes are involved, and patients will need chemotherapy. To determine if the mediastinal lymph nodes are involved, a CT scan of the chest is necessary. If the nodes are greater than 1 cm, then a biopsy is required. The lymph nodes are biopsied using mediastinoscopy. If they turn out to be negative, then lobectomy alone is sufficient.[10]

The status of the mediastinal lymph nodes is also important when dealing with patients with sarcoidosis, lymphoma, and tuberculosis. In each of these cases, a mediastinoscopy is necessary to assess the histology before treatment can be provided.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Mediastinum, Transverse Section of the Thorax. The Mediastinum, a transverse section of the thorax, showing the contents of the middle and the posterior mediastinum, left phrenic nerve, heart, lungs, pulmonary pleura, and costal pleura.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Adeyinka A, Pierre L. Air Leak. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020594]

Volpe JK, Makaryus AN. Anatomy, Thorax, Heart and Pericardial Cavity. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29494059]

Stauffer CM, Meshida K, Bernor RL, Granite GE, Boaz NT. Anatomy, Thorax, Pericardiacophrenic Vessels. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32644668]

Isaka T,Mitsuboshi S,Maeda H,Kikkawa T,Oyama K,Murasugi M,Kanzaki M,Onuki T, Anatomical analysis of the left upper lobe of lung on three-dimensional images with focusing the branching pattern of the subsegmental veins. Journal of cardiothoracic surgery. 2020 Sep 29; [PubMed PMID: 32993708]

Cho TH, Kim SH, O J, Kwon HJ, Kim KW, Yang HM. Anatomy of the thoracic paravertebral space: 3D micro-CT findings and their clinical implications for nerve blockade. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2021 Aug:46(8):699-703. doi: 10.1136/rapm-2021-102588. Epub 2021 May 14 [PubMed PMID: 33990438]

Gilday C, Odunayo A, Hespel AM. Spontaneous Pneumothorax: Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis. Topics in companion animal medicine. 2021 Nov:45():100563. doi: 10.1016/j.tcam.2021.100563. Epub 2021 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 34303864]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTran J, Haussner W, Shah K. Traumatic Pneumothorax: A Review of Current Diagnostic Practices And Evolving Management. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2021 Nov:61(5):517-528. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2021.07.006. Epub 2021 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 34470716]

Hu K,Chopra A,Kurman J,Huggins JT, Management of complex pleural disease in the critically ill patient. Journal of thoracic disease. 2021 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 34527360]

Ferreiro L, Toubes ME, San José ME, Suárez-Antelo J, Golpe A, Valdés L. Advances in pleural effusion diagnostics. Expert review of respiratory medicine. 2020 Jan:14(1):51-66. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2020.1684266. Epub 2019 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 31640432]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGhigna MR, Thomas de Montpreville V. Mediastinal tumours and pseudo-tumours: a comprehensive review with emphasis on multidisciplinary approach. European respiratory review : an official journal of the European Respiratory Society. 2021 Dec 31:30(162):. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0309-2020. Epub 2021 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 34615701]