Introduction

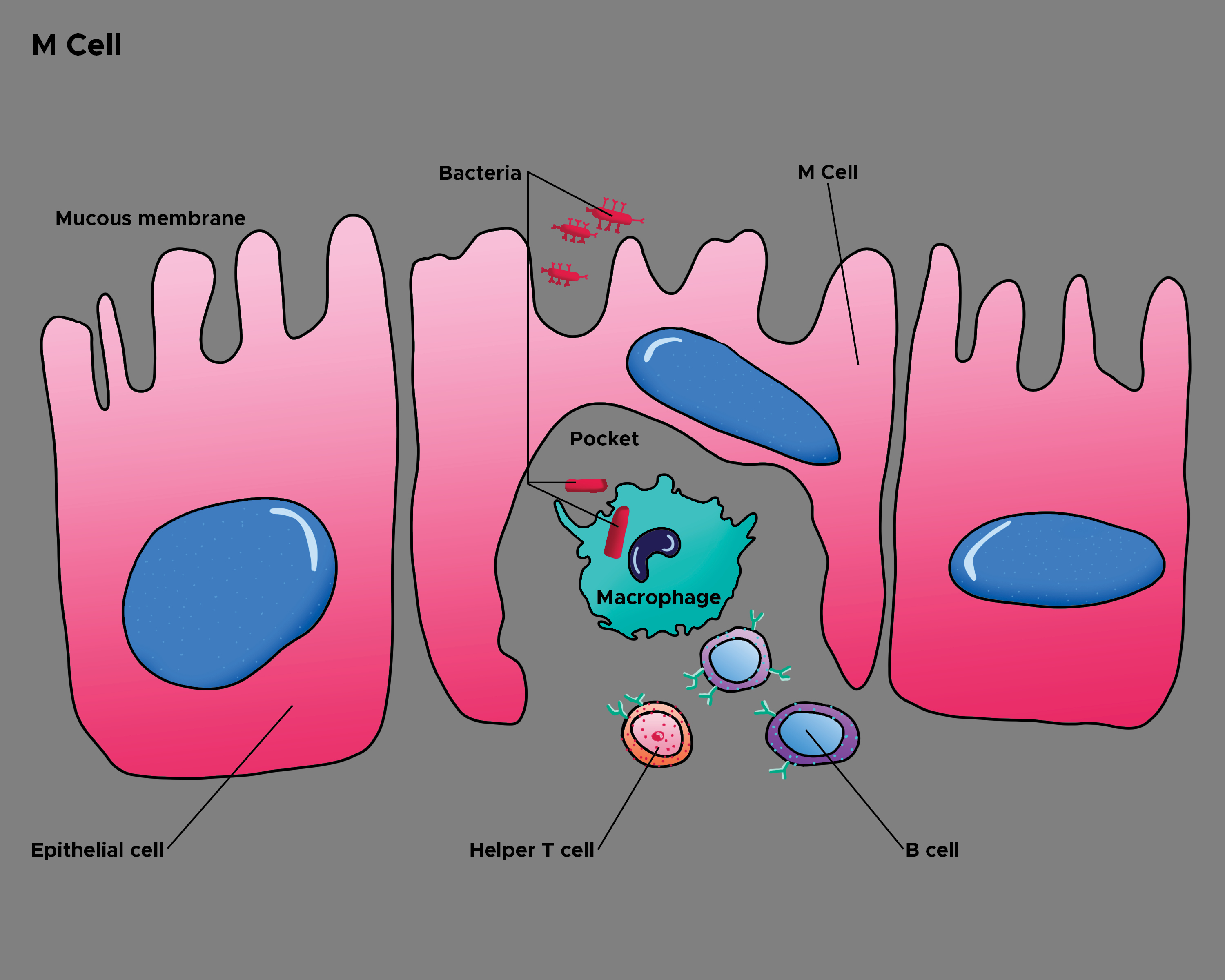

M cells (or microfold cells, a name given due to their unique structure) are specialized intestinal epithelial cells that are primarily found overlying gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) lymphoid follicles such as the Peyer’s patches in the ileum (see Image. Epithelial Cells and M Cells). These cells do not possess normal intestinal microvilli, in contrast to normal intestinal enterocytes (epithelial cells), and are specialized to sample macromolecules (antigens and pathogens). M cells function to sample and transport antigens/pathogens from the luminal surface to the sub-epithelium (a process also known as transcytosis), where macrophages and other immune cells process the antigen/pathogens. This is achieved by a unique cellular structure involving many basolateral membrane invaginations that allow for the macrophages and other immune cells to initiate an immune response.

M cells play a vital role in immunity, allowing immune responses to occur in response to intestinal pathogens/antigens. It is likely that many, if not all, intestinal antigens are initially processed by M cells. Some note that a decrease in M cells leads to failing immunity, such as in old age or chemotherapeutic states. It has been noted that many pathogens exploit this immune surveillance system, using the M cells as a method to gain access to the bloodstream/other parts of the body. Several intestinal pathogens also specifically target M cells to avoid immune processing. The unique method of M-cell, trans-epithelial transport is also being explored as an intestinal drug and vaccine delivery option. There is still much research being done involving M cells, and it is likely that in 5 years or less, this topic will be further expanded.

Structure

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure

M cells differ structurally from normal intestinal mucosal cells. M cells have apical microfolds, hence their alternate name, "microfold cells." These apical microfolds are poorly organized villi that have unique adhesion molecules to grab and sample luminal macromolecules. They have a thin glycocalyx, as opposed to the normally thick glycocalyx of other mucosal epithelial cells, that allows for adhesion but also does not impend the transport of molecules.[1][2] They have a unique intraepithelial invagination, or "pocket," on the basolateral surface that can also be seen via electron microscopy. These invaginations allow macrophages and other immune cells to process the engulfed macromolecules in a short time, decreasing the time from transport to processing.[1][3]

Function

M cells function as sentries against intestinal toxins and/or pathogens, transporting them (trans-epithelial) to awaiting immune cells. M cells specialize in transcytosis (ie, trans-epithelial transport). M cells uptake macromolecules (antigens, pathogens) from their apical surface (intestinal luminal surface) and transport these molecules, via vesicles, to the basolateral surface. This transport appears to be non-selective; however, some specialized adhesion and transport markers have been noted, such as in the case of Vibrio uptake. There also are several basolateral invaginations which house macrophages and other immune cells. These immune cells process the presented molecules and deliver them further onto intestinal lymphoid follicles to initiate an immune response.[4][5][6] This function has been known to be exploited as a method to gain entry into the body past the intestinal epithelial barrier.

Tissue Preparation

These cells lack typical enterocyte glycoproteins, mainly alkaline phosphatase and sucrase-isomaltase. These are used as negative markers for the identification of M cells. Due to their shortened, irregular microvilli, M cells also stain poorly for actin, villi, and other microvilli-associated proteins. This lack of villous staining can be further used to identify M cells.[1]

Histochemistry and Cytochemistry

Specific glycosylation patterns and lectins appear to vary among M cells, although some lectins have been used to characterize M cells. The ulex europaeus agglutinin-1 and winged bean basic agglutinin lectins have been used to stain specifically for M cells, though it is not clear how commonly these lectins are involved with M cells.[1] M cells arise from LGLgr5 stem cells found in the intestinal crypts. RANKL expression, among various tumor necrosis factors and other cytokines, is needed to signal the development of M cells from the stem cells mentioned above. Deletions or functional modifications of RANKL have been linked to M cell deficiency.[7][8][9]

Microscopy, Light

On light microscopy, M cells can be seen to have an absence of thick microvilli on their apical (luminal) surface and "pockets" of immune cells within their basolateral borders. Otherwise, electron microscopy and/or immunochemistry are used to identify these cells.[1]

Microscopy, Electron

M cells have apical microfolds on electron microscopy (hence their alternate name, "microfold cells"). These apical microfolds are poorly organized villi that have unique adhesion molecules to grab and sample luminal macromolecules. They have a unique intraepithelial invagination (or "pocket") on the basolateral surface can also be seen via electron microscopy. These invaginations allow for macrophages and other immune cells to process the engulfed macromolecules.[1]

Clinical Significance

M cells are important for maintaining mucosal immunity function, particularly in the intestines. The immunologic reaction to many common intestinal pathogens, such as various Vibrio species, depends on initial uptake by M cells.[1][10] It has been noted that in aged mice, there is a decrease in M cells along the intestinal epithelial border, possibly playing a role in age-related immune dysfunction.[7][11] M cell damage has also been implicated in intestinal inflammation, where damaged M cells allow for unregulated uptake of inflammatory molecules/pathogens into the sub-epithelial space, potentiating the inflammatory process.[12] M-cell deficiency, leading to immunodeficiencies, is noted in cases of RANKL deletion/modification due to its role in M cell development.[8]

Numerous intestinal pathogens also exploit the function of M cells to gain entry into the sub-epithelium, notable ones being Shigella and Listeria. Salmonella has been noted to target and destroy M cells to both gain further entry into sub-epithelial tissues and avoid immunologic processing. Yersinia intestinal infections appear to use M cells as their primary method of entry into lymphoid follicles. Human immunodeficiency virus appears to use M cells as a method to spread and infect T cells based in mucosal lymphoid tissues.[1][4][13] M cells are being explored as vaccine and drug routes. Mucosal administration of many drugs and vaccines is often cheaper and safer than other methods. This route of administration also has the added benefit of engaging both the mucosal and systemic immune responses. Several studies have shown an ability to use M cells specifically to administer vaccines/drugs; however, the exact role efficiency of this method is still being explored.[14][15][16]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Corr SC, Gahan CC, Hill C. M-cells: origin, morphology and role in mucosal immunity and microbial pathogenesis. FEMS immunology and medical microbiology. 2008 Jan:52(1):2-12 [PubMed PMID: 18081850]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKraehenbuhl JP, Corbett M. Immunology. Keeping the gut microflora at bay. Science (New York, N.Y.). 2004 Mar 12:303(5664):1624-5 [PubMed PMID: 15016988]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGebert A, Rothkötter HJ, Pabst R. M cells in Peyer's patches of the intestine. International review of cytology. 1996:167():91-159 [PubMed PMID: 8768493]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOwen RL. Uptake and transport of intestinal macromolecules and microorganisms by M cells in Peyer's patches--a personal and historical perspective. Seminars in immunology. 1999 Jun:11(3):157-63 [PubMed PMID: 10381861]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKucharzik T, Lügering N, Rautenberg K, Lügering A, Schmidt MA, Stoll R, Domschke W. Role of M cells in intestinal barrier function. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2000:915():171-83 [PubMed PMID: 11193574]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRosner AJ, Keren DF. Demonstration of M cells in the specialized follicle-associated epithelium overlying isolated lymphoid follicles in the gut. Journal of leukocyte biology. 1984 Apr:35(4):397-404 [PubMed PMID: 6200555]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMabbott NA, Kobayashi A, Sehgal A, Bradford BM, Pattison M, Donaldson DS. Aging and the mucosal immune system in the intestine. Biogerontology. 2015 Apr:16(2):133-45. doi: 10.1007/s10522-014-9498-z. Epub 2014 Apr 5 [PubMed PMID: 24705962]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSehgal A, Kobayashi A, Donaldson DS, Mabbott NA. c-Rel is dispensable for the differentiation and functional maturation of M cells in the follicle-associated epithelium. Immunobiology. 2017 Feb:222(2):316-326. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2016.09.008. Epub 2016 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 27663963]

Rouch JD, Scott A, Lei NY, Solorzano-Vargas RS, Wang J, Hanson EM, Kobayashi M, Lewis M, Stelzner MG, Dunn JC, Eckmann L, Martín MG. Development of Functional Microfold (M) Cells from Intestinal Stem Cells in Primary Human Enteroids. PloS one. 2016:11(1):e0148216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148216. Epub 2016 Jan 28 [PubMed PMID: 26820624]

Rios D, Wood MB, Li J, Chassaing B, Gewirtz AT, Williams IR. Antigen sampling by intestinal M cells is the principal pathway initiating mucosal IgA production to commensal enteric bacteria. Mucosal immunology. 2016 Jul:9(4):907-16. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.121. Epub 2015 Nov 25 [PubMed PMID: 26601902]

Schmucker DL, Thoreux K, Owen RL. Aging impairs intestinal immunity. Mechanisms of ageing and development. 2001 Sep 15:122(13):1397-411 [PubMed PMID: 11470129]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGullberg E, Söderholm JD. Peyer's patches and M cells as potential sites of the inflammatory onset in Crohn's disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006 Aug:1072():218-32 [PubMed PMID: 17057202]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOwen RL. M cells as portals of entry for HIV. Pathobiology : journal of immunopathology, molecular and cellular biology. 1998:66(3-4):141-4 [PubMed PMID: 9693315]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWang M, Gao Z, Zhang Z, Pan L, Zhang Y. Roles of M cells in infection and mucosal vaccines. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2014:10(12):3544-51. doi: 10.4161/hv.36174. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25483705]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTakahashi K, Yano A, Watanabe S, Langella P, Bermúdez-Humarán LG, Inoue N. M cell-targeting strategy enhances systemic and mucosal immune responses induced by oral administration of nuclease-producing L. lactis. Applied microbiology and biotechnology. 2018 Dec:102(24):10703-10711. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-9427-1. Epub 2018 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 30310964]

Azizi A, Kumar A, Diaz-Mitoma F, Mestecky J. Enhancing oral vaccine potency by targeting intestinal M cells. PLoS pathogens. 2010 Nov 11:6(11):e1001147. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001147. Epub 2010 Nov 11 [PubMed PMID: 21085599]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence