Introduction

Malassezia furfur is a member of a monophyletic genus of fungi normally found on human and animal skin. These lipid-dependent, commensal yeasts normally constitute greater than 80% of the total fungal population of human skin and are frequently isolated in both healthy and diseased hosts.[1] Malassezia spp. have been implicated in several common dermatologic disorders, including seborrheic dermatitis (SD), pityriasis versicolor (PV), and Malassezia folliculitis. Recently, emerging evidence suggests Malassezia may contribute to other conditions such as atopic dermatitis (AD) and psoriasis. However, their exact pathogenic role remains a subject of controversy.[2] Nevertheless, studies demonstrate that a reduction in the number of Malassezia with antifungal agents leads to the improvement of some skin conditions.[3] In immunocompromised patients, Malassezia can act opportunistically, causing severe cutaneous and systemic infections.[4]

Researchers discovered a yeast that correlated with PV as early as 1846, which was later named Malassezia furfur in 1853. First designated as a distinct genus in 1889, over the years, 17 species of Malassezia have since been isolated from both human and animal skin, which are classified by molecular biology, morphology, phenotype, and ultrastructure.[5] Among the species, M. globosa, M. restricta, and M. sympodialis are the most common types found on healthy and diseased human skin, but M. furfur is also prevalent, and reports exist specifically correlating it with multiple skin disorders, PV in particular.[6] This article will focus on the most common skin conditions related to M. furfur – SD, PV, and Malassezia folliculitis.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

M. furfur is unable to synthesize fatty acids independently and, therefore, depends on the oils produced in areas of the skin rich in sebaceous glands, especially the trunk, face, and scalp. Although it is a commensal microorganism that is a typical component present on the stratum corneum of human skin, infection results when the dimorphic yeast changes to its mycelial form.[7][8]

Epidemiology

M. furfur ubiquitously colonizes adults and even infants by age 3 to 6 months, and it does not have a predilection for any particular age or sex.[9]

SD affects 1 to 3% of the general population, and this rate would be even higher with the inclusion of milder cases of dandruff. Immunocompromised patients have the highest incidence of up to 33%. SD has a seasonal pattern as it occurs more commonly in the winter months. There is a slight male predominance and a bimodal incidence peaking in adolescence and again after age 50. It has an association with various diseases, including depression, HIV, Parkinson disease, and spinal injuries.[7][8][10][11]

In PV, adults age 20 to 50 are most commonly affected when sebaceous gland activity is at its peak. Incidence is higher in the summer months and tropical areas, as prevalence approaches 40% in these regions. PV may also represent up to 3% of dermatology visits in temperate areas.[7][8]

Malassezia folliculitis also more commonly occurs in hot and humid environments. It correlates with immunosuppression and often occurs concomitantly with acne and other Malassezia conditions, including SD and PV. This condition may comprise 1% to 1.5% of outpatient dermatology visits in China.[12]

Recently, studies have evaluated the effectiveness of culture-independent-based methods (e.g., molecular techniques such as PCR) as a modality to assess Malassezia population epidemiology as opposed to conventional culture-based methods. Both techniques have advantages and drawbacks. Whereas culture-based methods offer the ability to discern specific virulence factors, molecular procedures allow rapid, accurate identification and quantification of Malassezia spp. The latter has helped isolate M. furfur in deep-seated infections in immunocompromised patients and preterm infants in the neonatal intensive care unit who received lipid-laden nutrition via catheters. The use of these techniques in the future appears promising, but they are not currently available for clinical use.[12][13]

Pathophysiology

The exact pathogenic role of Malassezia spp. in skin disease is not entirely understood. Whereas PV is a superficial fungal infection that may involve high fungal load without significant inflammation, AD, Malassezia folliculitis, psoriasis, and SD are disorders inherently characterized by inflammation. The disease most likely occurs as a multifactorial process involving yeast enzymatic action on the skin, interaction with the host immune system, and environmental and genetic factors. Furthermore, Malassezia colonization can exacerbate existing dermatoses and act opportunistically in immunocompromised individuals.[4][14]

Histopathology

In PV, specimens should be obtained by scraping the periphery of a scaling lesion to optimize fungal yield for direct microscopy. Before staining, a 10% potassium hydroxide solution is then applied to dissolve keratin and debris. Under light microscopy, visualization of spores and hyphae are diagnostic and classically appear as "spaghetti and meatballs." Although direct microscopy is preferred, a biopsy is an option as well. After staining with periodic acid-Schiff or methenamine silver, short hyphae and round budding along with pigment incontinence may be visible in the stratum corneum and keratinocytes.[7][8] Inflammation is often less apparent than biopsies of tinea, and Malassezia is often more visible on routine H&E stain.

A biopsy taken of SD may show findings characteristic of one of two stages. Acutely, superficial perivascular and perifollicular inflammatory infiltrates, spongiosis, psoriasiform hyperplasia, and parakeratosis around follicular opening may appear. Chronic lesions may appear similar to psoriasis, displaying psoriasiform hyperplasia and parakeratosis with dilation of venules of the surface plexus.[11]

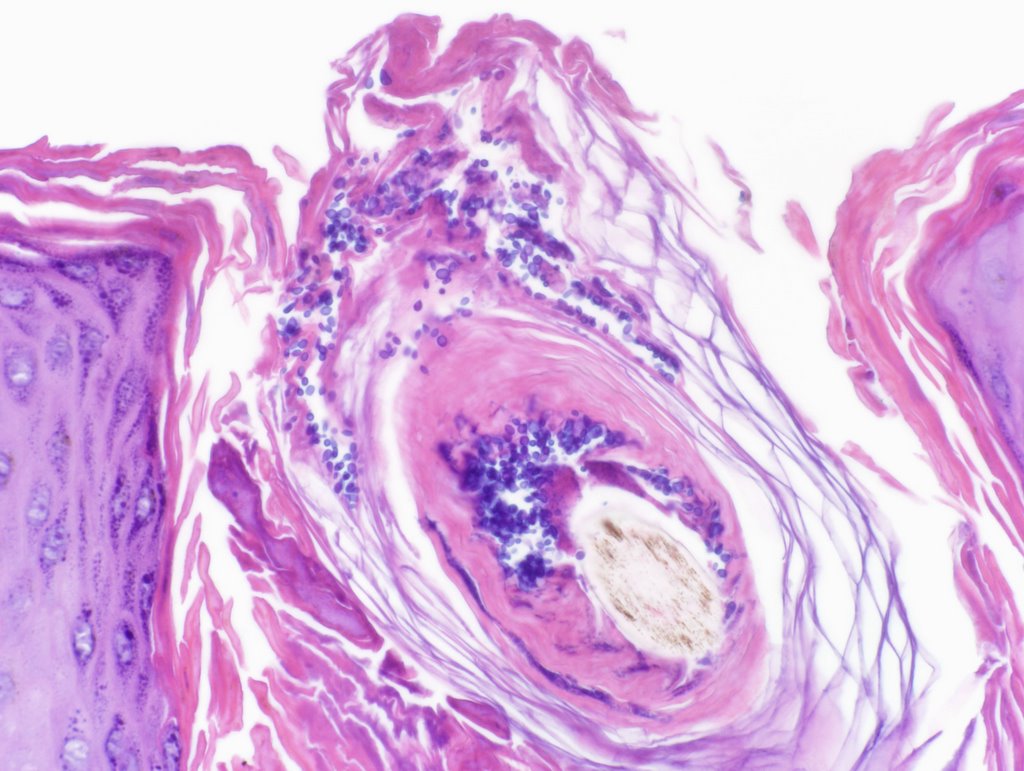

On biopsy, Malassezia folliculitis will show a follicle dilated by suppurative inflammation with a few small yeast forms. Sometimes budding and a few hyphae may present. Nonspecific findings occur seen in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis.[7]

History and Physical

SD presents as variable degrees of erythematous, greasy, flaking plaques that predominantly affects the scalp, nasolabial folds, eyebrows, and chest. Dandruff appears similarly but less severe as red, oily, scaly patches on the scalp that may be pruritic. SD is typically self-limited in children, and the most common presentation is scalp involvement, so-called "cradle cap."

PV characteristically demonstrates multiple round to oval macules, patches, or plaques that vary in color (hence the name, versicolor), ranging from hypopigmented to a hyperpigmented red, blue, pink, or grey. Lesions may have peripheral scaling and pruritis.

Malassezia folliculitis may appear clinically similar to acne as erythematous papules and pustules with or without pruritis. Some studies report the most common lesions are dome-shaped, comedopapules with a central "dell" not unlike molluscum contagiosum. Patients are often hospitalized in the intensive care unit or immunosuppressed on biologic agents or chemotherapy. [12]

In immunocompromised patients, the clinical manifestations of fungemia and sepsis are nonspecific. Patients are typically critically ill and suddenly develop fevers, chills, lethargy, and signs and symptoms of internal organ involvement. Yeasts may gain venous access through central venous catheters or parenteral lines.[4]

Evaluation

The diagnosis for most conditions associated with M. furfur is clinical. However, given the variability of clinical features and similar presentations to other diseases, microscopic examination with KOH preparation is preferred for cutaneous disorders. Biopsy of lesions such as Malassezia folliculitis and psoriasis may be necessary if refractory to treatment or certainty of diagnosis is in doubt. In PV, Wood's light may aid in diagnosis by inducing yellow-gold fluorescence of lesions colonized with M. furfur, although positive examination only results in about one-third of cases.[7] A high index of suspicion is needed to diagnose fungemia. Yeasts are readily detectable by microscopy utilizing Giemsa. Detection by culture-based methods, however, may be difficult and time-consuming. More recently, molecular diagnostic methods have been introduced but are not yet available for clinical use.[4]

Treatment / Management

Most of the current literature regarding the treatment of Malassezia includes diseases with which it is most closely associated, that is, SD, PV, and Malassezia folliculitis. In general, Malassezia spp. are susceptible to topical and oral agents with keratolytic and anti-inflammatory properties, as well as antifungal activity. Shampoos and creams with selenium and zinc salts, propylene glycol, and compounds with sulfur were among the first treatments introduced and are often effective. Topical treatment can also employ specific antifungals, including azoles and terbinafine. More severe, diffuse, or recalcitrant disease may require oral antifungal therapy. Oral terbinafine is less effective than topical for PV. Historically, topical and oral corticosteroids were therapeutic choices for SD, but antifungals and even topical tacrolimus and pimecrolimus have demonstrated promising results.[7][12]

The main goal in the treatment of SD is to reduce Malassezia proliferation and the resultant inflammatory response. First-line therapy includes topicals with fungistatic and fungicidal properties, topical antifungals, or corticosteroids. Zinc pyrithione, selenium sulfide, and ciclopirox olamine 1%, available in shampoos, cream, and gel, are commonly implemented due to their antifungal, keratolytic, and anti-inflammatory properties. Topic azoles, such as ketoconazole 2% and fluconazole 2% shampoos, are effective and well-tolerated. They are useable in conjunction with topical corticosteroids for additional anti-inflammatory effects. For extensive or recalcitrant SD, oral ketoconazole, 200 mg for four weeks or itraconazole, 200 mg daily for one week have proven effective. Similarly, topical antifungals are first-line against PV, including imidazoles, ciclopirox olamine, selenium sulfide, and zinc pyrithione shampoos, salicylic acid preparations, and benzoyl peroxide. Systemic antifungal therapy is an option in conjunction with topicals or alone in cases of more extensive involvement or resistant disease. Similar therapy may work for Malassezia folliculitis.[11][15][16](A1)

Invasive Malassezia infection warrants prompt removal of central venous catheters due to the yeast's ability to produce biofilms. This rare occurrence lacks effective evidence-based practices, but studies have demonstrated Malassezia susceptibility to antifungal triazoles, and amphotericin B. Intravenous therapy may transition to oral after a two-week course.[4]

Differential Diagnosis

Although the diagnosis of SD is usually clinical, clinicians should consider other skin conditions when the presentation is atypical or not responsive to treatment. SD can be challenging to distinguish from psoriasis. Cutaneous manifestations of psoriasis are typically more erythematous with prominent silvery scaling, and plaques are well demarcated. Psoriatic arthritis and nail changes may be present, and it is essential to determine a family history. Rosacea also causes facial erythema, but papules, pustules, and telangiectasis with no scaling occur on the nose and malar and perioral areas. Although atopic dermatitis should be a consideration when presumed SD is refractory to treatment, significant pruritis may be a distinguishing factor, and patch testing can confirm the diagnosis. Secondary syphilis, "the great imitator," may present as multiple psoriasiform lesions and should be tested for with serologic testing when the index of suspicion is high. The malar erythema seen in acute systemic lupus erythematosus may be mistaken for SD, although the former does not affect the nasolabial folds or cross the bridge of the nose. Pemphigus foliaceous presents with erythematous lesions on the head and scalp that extend to the trunk. Prominent features include scaling, crusting, erosions, and pain. Pathohistological and serologic testing secure the diagnosis. In children, tinea infections and diaper dermatitis merit consideration.[11]

Several dermatologic disorders may mimic PV. SD may occur on the trunk as PV does, but lesions are more erythematous with thicker scaling, and other locations, including the scalp, are usually involved. Pityriasis rosea may be differentiated from PV by the appearance of a herald patch before the onset of symptoms, "Christmas tree" distribution, and erythematous, scaling macules and patches. Whereas PV causes hypopigmented skin lesions, those seen in vitiligo are depigmented. The eczematous lesions of pityriasis alba also may appear as hypopigmented macules and patches; however, the face is primarily affected, and affected children typically have a history of atopy. Secondary syphilis must be ruled out in a patient with generalized hyperpigmented macules involving the palms and soles. Mycosis fungoides may present as hypopigmented lesions on the trunk and extremities, but scaling, erythema, and plaques are more characteristic.[17]

Folliculitis may result from other microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses. Vesicles on an erythematous base and umbilicated papules are characteristic of herpes simplex and papillomavirus folliculitis, respectively. Both bacterial and fungal folliculitis may present with painful, pruritic follicular papules and pustules, so taking a thorough history of risk factors and progression is critical. KOH preparation and cultures definitively confirm the diagnosis. The presence of open and closed comedones and the lack of pruritis suggests acne vulgaris over Malassezia folliculitis.

Prognosis

Skin disorders linked to M. furfur are chronic and relapsing for susceptible individuals. Immunosuppressed patients have higher rates of recurrence. Specific environmental exposures may worsen or improve symptoms, as cold weather aggravates SD, and PV is seen more commonly during summer months. PV generally responds to topical treatment, though the pigment alteration after infection can take months to resolve.

Complications

For the most part, dermatologic disorders caused by M. furfur are relatively benign. However, the cosmetic appearances are often accompanied by social stigmas, which may be significantly emotionally distressing to patients. Secondary bacterial and viral infections may complicate SD and atopic dermatitis. As discussed above, fungemia is a rare but serious complication occurring when normal skin flora gains parenteral access, and opportunistically causes systemic infection in immunosuppressed patients.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients require education that M. furfur is one of a group of common commensal yeasts that normally inhabit human skin but may cause a variety of common dermatologic disorders. These conditions, including SD, PV, and Malassezia folliculitis, are benign and not contagious.

The appearance and symptoms of diseases linked with M. furfur vary widely among patients. For example, PV may present with lesions that appear different colors on patients with lighter or darker skin types and typically worsen in hot and humid conditions. To confirm the diagnosis, a physician will examine a skin scraping specimen under a microscope.

Treatment consists of using topical agents, such as special shampoos or creams, or pills taken by mouth for more extensive involvement. Consistent use of the shampoo may mitigate future occurrences. Physicians may recommend over-the-counter or prescription medications if itching is a significant symptom.

Pearls and Other Issues

Patients receiving systemic therapy require follow-up examinations to evaluate clinical response to treatment as well as monitoring for adverse effects of medications. Antifungal drugs are known to interact with other drugs and affect hepatic, renal, and hematopoietic functioning. Periodic blood testing to monitor for toxicity is thus necessary.[16]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Due to its ubiquitous nature, myriad health care professionals encounter patients affected by M. furfur daily. Dermatologists, internists, mid-levels, nurses, and other specialists will commonly see patients with these dermatoses either as a chief complaint or incidental finding. The interprofessional team includes the pharmacist and nursing, in particular, dermatology specialty-trained nurses. It is thus essential for the clinician to have a solid working knowledge of commensal microorganisms such as M. furfur and their pathogenic role, methods of diagnosis, and treatment.

When the clinician or specialist addresses these conditions, they should enlist the assistance of the other members of the interprofessional healthcare team. Dermatology specialty nursing staff can answer patient questions, explain treatment options, assess therapeutic progress, and evaluate patient compliance. The pharmacist will verify agent selection and dosing, and check for any potential drug-drug interactions. Both the nurse and pharmacist must report any findings or concerns to the clinician/prescriber immediately, so intervention can occur if needed. These interprofessional team dynamics will result in better patient outcomes. [Level 5]

Since SD and PV are predominantly chronic, recurrent conditions, susceptible patients may require long-term collaboration with a clinician to achieve improvement in clinical manifestations and symptoms. After initial treatment, prophylactic and maintenance therapies, along with avoidance of precipitating factors (i.e., cold weather for SD and warm, humid conditions for PV), may lead to sustained remission.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Gao Z, Perez-Perez GI, Chen Y, Blaser MJ. Quantitation of major human cutaneous bacterial and fungal populations. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2010 Oct:48(10):3575-81. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00597-10. Epub 2010 Aug 11 [PubMed PMID: 20702672]

Difonzo EM, Faggi E. Skin diseases associated with Malassezia species in humans. Clinical features and diagnostic criteria. Parassitologia. 2008 Jun:50(1-2):69-71 [PubMed PMID: 18693561]

Prohic A, Jovovic Sadikovic T, Krupalija-Fazlic M, Kuskunovic-Vlahovljak S. Malassezia species in healthy skin and in dermatological conditions. International journal of dermatology. 2016 May:55(5):494-504. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13116. Epub 2015 Dec 29 [PubMed PMID: 26710919]

Tragiannidis A, Bisping G, Koehler G, Groll AH. Minireview: Malassezia infections in immunocompromised patients. Mycoses. 2010 May:53(3):187-95. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2009.01814.x. Epub 2009 Dec 17 [PubMed PMID: 20028460]

Cabañes FJ, Theelen B, Castellá G, Boekhout T. Two new lipid-dependent Malassezia species from domestic animals. FEMS yeast research. 2007 Sep:7(6):1064-76 [PubMed PMID: 17367513]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAshbee HR. Update on the genus Malassezia. Medical mycology. 2007 Jun:45(4):287-303 [PubMed PMID: 17510854]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGupta AK, Batra R, Bluhm R, Boekhout T, Dawson TL Jr. Skin diseases associated with Malassezia species. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2004 Nov:51(5):785-98 [PubMed PMID: 15523360]

Warner RR, Schwartz JR, Boissy Y, Dawson TL Jr. Dandruff has an altered stratum corneum ultrastructure that is improved with zinc pyrithione shampoo. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2001 Dec:45(6):897-903 [PubMed PMID: 11712036]

Ashbee HR, Leck AK, Puntis JW, Parsons WJ, Evans EG. Skin colonization by Malassezia in neonates and infants. Infection control and hospital epidemiology. 2002 Apr:23(4):212-6 [PubMed PMID: 12002236]

Farthing CF, Staughton RC, Rowland Payne CM. Skin disease in homosexual patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and lesser forms of human T cell leukaemia virus (HTLV III) disease. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 1985 Jan:10(1):3-12 [PubMed PMID: 4039236]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBorda LJ, Wikramanayake TC. Seborrheic Dermatitis and Dandruff: A Comprehensive Review. Journal of clinical and investigative dermatology. 2015 Dec:3(2):. doi: 10.13188/2373-1044.1000019. Epub 2015 Dec 15 [PubMed PMID: 27148560]

Gaitanis G, Magiatis P, Hantschke M, Bassukas ID, Velegraki A. The Malassezia genus in skin and systemic diseases. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2012 Jan:25(1):106-41. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00021-11. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22232373]

Theelen B, Cafarchia C, Gaitanis G, Bassukas ID, Boekhout T, Dawson TL Jr. Malassezia ecology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Medical mycology. 2018 Apr 1:56(suppl_1):S10-S25. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myx134. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29538738]

Saunders CW, Scheynius A, Heitman J. Malassezia fungi are specialized to live on skin and associated with dandruff, eczema, and other skin diseases. PLoS pathogens. 2012:8(6):e1002701. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002701. Epub 2012 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 22737067]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDessinioti C, Katsambas A. Seborrheic dermatitis: etiology, risk factors, and treatments: facts and controversies. Clinics in dermatology. 2013 Jul-Aug:31(4):343-351. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.01.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23806151]

Drake LA, Dinehart SM, Farmer ER, Goltz RW, Graham GF, Hordinsky MK, Lewis CW, Pariser DM, Skouge JW, Webster SB, Whitaker DC, Butler B, Lowery BJ, Elewski BE, Elgart ML, Jacobs PH, Lesher JL Jr, Scher RK. Guidelines of care for superficial mycotic infections of the skin: Pityriasis (tinea) versicolor. Guidelines/Outcomes Committee. American Academy of Dermatology. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1996 Feb:34(2 Pt 1):287-9 [PubMed PMID: 8642095]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMathur M, Acharya P, Karki A, Kc N, Shah J. Dermoscopic pattern of pityriasis versicolor. Clinical, cosmetic and investigational dermatology. 2019:12():303-309. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S195166. Epub 2019 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 31118732]