Introduction

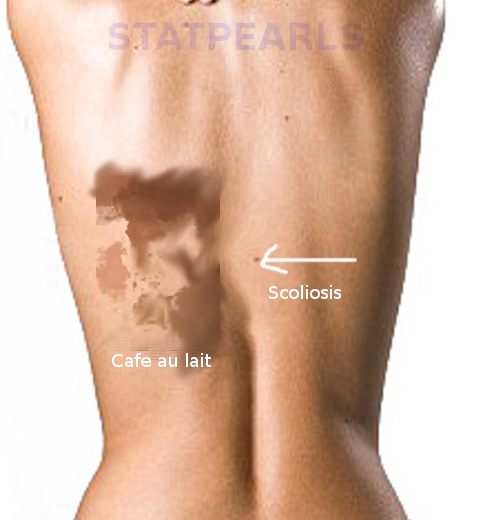

McCune-Albright syndrome is a rare genetic disordered originally recognized by the triad of polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, precocious puberty, and café-au-lait spots. A variety of endocrine disorders, including hyperthyroidism, acromegaly, phosphate wasting, and Cushing syndrome are now considered as part of the endocrinopathies seen in this disorder. The variable constellation of symptoms arises from a somatic activating mutation of the GNAS gene, which is present in many tissue types.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The cause of McCune-Albright syndrome is a spontaneous post zygotic missense mutation at ARG201 or Gln227 of the GNAS gene during embryogenesis. GNAS encodes the alpha subunit portion of a G-signaling complex that found in multiple tissue types, including bone, skin, and endocrine tissues. The mutation is distributed in a mosaic pattern and presenting signs and symptoms are dependent on the time frame the mutation occurs. Mutated GNAS results in a constitutively active alpha subunit, causing increased intracellular cAMP, and mediating the action of downstream hormones.[2]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of McCune-Albright syndrome is estimated to be between 1 in 100,000 to 1 in 1,000,000.[1]

Pathophysiology

An increase in intracellular cAMP signaling is responsible for the clinical manifestations of McCune-Albright syndrome. The phenotype is dependent on which tissue types the mutation occurs.[2] In bone, increased cAMP causes osteoblasts to differentiate into stromal cells while inhibiting further differentiation, resulting in fibrous dysplasia. These fibrous dysplastic lesions then exhibit increased secretion of phosphaturic hormone fibroblastic growth factor-23 (FGF23), causing renal phosphate wasting.[3] Increased cAMP signaling in the skin results in stimulation of melanin production via alpha-MSH, resulting in café-au-lait macules. Increased cAMP in endocrine tissue results in increased production and secretion of a specific hormone product. Affected endocrine tissues can include the gonads, thyroid, pituitary, parathyroid, and adrenal glands.[1]

Histopathology

Characteristics of fibrous dysplasia include an increased number of thin and irregular trabeculae. The marrow spaces get replaced by fibroblastic tissue. Lesions may be monostotic (involving one bone) or polyostotic (multiple bones involved). Commonly identified by radiograph, fibrodysplasia shows a hazy, radiolucent, ground-glass pattern due to defective mineralization.[3]

History and Physical

Initial clinical presentation is typically due to either precocious puberty or symptoms related to fibrous dysplasia. Females can present with vaginal bleeding and development of breast tissue. Males can present with testicular enlargement, appearance pubic and axillary hair, and increased body odor. Café-au-lait spots may be appreciated in retrospect unless they are prominent. These spots are typically midline and described as having “coast of Maine” jagged borders.[1]

Fibrous dysplastic lesions can present as a pathologic fracture or pain. Lesions of the calvarium and facial bones are common and can present as painless facial asymmetry. Radiographs reveal a characteristic lesion of thinning cortex and intramedullary “ground glass.”[4]

Symptoms of endocrinopathies are specific to the affected organ. Hyperthyroidism is common. Growth hormone and prolactin secretion present as acromegaly and disruption of normal gonadal function. Cushing syndrome is typically adrenal, presents in the neonatal period and is most commonly transient.[1]

Evaluation

McCune-Albright syndrome is largely a clinical diagnosis. Genetic testing for GNAS mutation is commercially available, however, due to the mosaicism, false negatives do occur, and a positive result contributes little to the clinical management.[2]

Evaluation includes radiographs or computed tomography (CT) to identify and characterize fibrodysplastic lesions. In early childhood, patients with McCune-Albright syndrome are more likely to experience stress fractures that may lead to permanent deformity if not stabilized. CT scan of the skull helps in the diagnosis of craniofacial bone lesions and pituitary lesions. Regular vision and hearing tests can monitor lesions affecting those systems. Baseline bone scan with 99Tc-methyl diphosphate is indicated in endocrinopathies that affect bone development.[5]

Precocious puberty in McCune-Albright syndrome is typically peripheral and due to activation of ovarian or testicular tissue. Evaluation includes serum estradiol and testosterone levels. Boys should have a testicular ultrasound to assess for hormonally active tumors. High levels of estradiol in girls may cause activation of hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, triggering evaluation for central precocious puberty. Additionally, GnRH stimulation testing and serum measurements of luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone may be warranted.[6]

Evaluation for growth hormone excess includes oral glucose tolerance test and serum growth hormone and prolactin measurements. Evaluation of hyperthyroidism includes measurement of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), free and bound thyroxine, and T3. Periodic ultrasound is recommended with an appropriate follow-up of any abnormal findings. Monitoring levels of serum phosphate and renal reabsorption of phosphate is also a recommendation.[7][8]

Treatment / Management

The mainstay treatment of gonadotropin-independent precocious puberty is aromatase inhibitors and more recently tamoxifen in females. In the case of the development of central precocious puberty, steady-state gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs are used to downregulate hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis.[9][10][11]

Treatment of hyperthyroidism is initially managed medically with antithyroid medications and radioablation. Growth hormone excess treatment is by somatostatin or direct GH receptor antagonists. Hyperprolactinemia management is with bromocriptine. In patients with demonstrated pituitary adenomas, surgical resection of the adenoma is an option. Treatment of hypophosphatemia with oral supplementation is under debate, but supplementation should be used in the setting of rickets.[7][8](B3)

No definitive guidelines for surgical intervention of fibrous dysplastic lesions exist. However, common indications for surgical stabilization include progression of pain, stress fracture, deformity, or loss of function. The data for prophylactic surgery are lacking. Studies investigating the use of high dose bisphosphonates show mixed results, and currently, the only indication for bisphosphonate therapy is pain relief. Surgical intervention due to cranial-facial lesions may be necessary when there is a potential for loss or sight or hearing.

Differential Diagnosis

Neurofibromatosis and McCune-Albright syndrome both can present with café-au-lait macules. The café-au-lait macules of neurofibromatosis typically have smooth borders, while the macules of McCune-Albright are midline and have a jagged or irregular appearance. Additionally, neurofibromatosis characteristically presents with neurofibromas, which are lacking in McCune-Albright syndrome.[1]

Fibrous dysplasia is common as an isolated finding of single or multiple lesions. While some lesions are caused by the same GNAS mutation as McCune-Albright, in the absence of endocrinopathy and café-au-lait macules, the diagnosis of isolated fibrous dysplasia is more likely.[2]

Precocious puberty may be central or peripheral and in females is often idiopathic. Hormonally active tumors and congenital adrenal hyperplasia are other diagnostic considerations in patients presenting with precocious puberty. Patients presenting with precocious puberty should undergo skeletal survey to rule out McCune-Albright syndrome.[6]

Prognosis

Prognosis may be challenging to ascertain due to the varying severity of the disease. Younger patients with renal phosphate wasting and polyostotic lesions have a higher risk of clinically relevant bone pain and fracture.[12]

The primary treatment goal of precocious puberty is the preservation of potential adult height. Without intervention, growth plates close prematurely resulting in short stature.[9]

While rare, there is potential for malignant transformation of fibrous dysplastic lesions.[3] There are also reports of increased breast cancer risk.[1]

Complications

Possible complications include pain and fracture at sites of fibrous dysplastic lesions. Because of phosphate wasting, there is an increased risk of developing rickets.

Decreased adult stature is the main complication of untreated precocious puberty.[6]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients and parents should receive counseling that the cause of McCune-Albright syndrome a spontaneous mutation and is not vertically transmittable to offspring.[1] Due to the wide variety of endocrinopathies, patients should receive close follow up with measurement of bone maturity and hormone levels.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Given the wide variety of manifestations, many key specialists may be involved in patient care, including but not limited to pediatric orthopedic surgery, pediatric endocrinology, and physical therapy. Personalized care coordination is vital between pediatricians and pediatric nursing who need to maintain a high index of suspicion in recognizing endocrinopathies and pathologic fractures in McCune-Albright syndrome.

Media

References

Dumitrescu CE, Collins MT. McCune-Albright syndrome. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2008 May 19:3():12. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-3-12. Epub 2008 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 18489744]

Turan S, Bastepe M. GNAS Spectrum of Disorders. Current osteoporosis reports. 2015 Jun:13(3):146-58. doi: 10.1007/s11914-015-0268-x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25851935]

Leet AI, Collins MT. Current approach to fibrous dysplasia of bone and McCune-Albright syndrome. Journal of children's orthopaedics. 2007 Mar:1(1):3-17. doi: 10.1007/s11832-007-0006-8. Epub 2007 Feb 23 [PubMed PMID: 19308500]

Belsuzarri TA, Araujo JF, Melro CA, Neves MW, Navarro JN, Brito LG, Pontelli LO, de Abreu Mattos LG, Gonçales TF, Zeviani WM. McCune-Albright syndrome with craniofacial dysplasia: Clinical review and surgical management. Surgical neurology international. 2016:7(Suppl 6):S165-9. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.178567. Epub 2016 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 27057395]

Leet AI, Chebli C, Kushner H, Chen CC, Kelly MH, Brillante BA, Robey PG, Bianco P, Wientroub S, Collins MT. Fracture incidence in polyostotic fibrous dysplasia and the McCune-Albright syndrome. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2004 Apr:19(4):571-7 [PubMed PMID: 15005844]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBercaw-Pratt JL, Moorjani TP, Santos XM, Karaviti L, Dietrich JE. Diagnosis and management of precocious puberty in atypical presentations of McCune-Albright syndrome: a case series review. Journal of pediatric and adolescent gynecology. 2012 Feb:25(1):e9-e13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2011.09.005. Epub 2011 Nov 3 [PubMed PMID: 22051789]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShetty S, Varghese RT, Shanthly N, Paul TV. Toxic Thyroid Adenoma in McCune-Albright Syndrome. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2014 Feb:8(2):281-2. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/6993.4083. Epub 2014 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 24701557]

Chakraborty D, Mittal BR, Kashyap R, Manohar K, Bhattacharya A, Bhansali A. Radioiodine treatment in McCune-Albright syndrome with hyperthyroidism. Indian journal of endocrinology and metabolism. 2012 Jul:16(4):654-6. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.98035. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22837937]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChen M, Eugster EA. Central Precocious Puberty: Update on Diagnosis and Treatment. Paediatric drugs. 2015 Aug:17(4):273-81. doi: 10.1007/s40272-015-0130-8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25911294]

Estrada A, Boyce AM, Brillante BA, Guthrie LC, Gafni RI, Collins MT. Long-term outcomes of letrozole treatment for precocious puberty in girls with McCune-Albright syndrome. European journal of endocrinology. 2016 Nov:175(5):477-483 [PubMed PMID: 27562402]

de G Buff Passone C, Kuperman H, Cabral de Menezes-Filho H, Spassapan Oliveira Esteves L, Lana Obata Giroto R, Damiani D. Tamoxifen Improves Final Height Prediction in Girls with McCune-Albright Syndrome: A Long Follow-Up. Hormone research in paediatrics. 2015:84(3):184-9. doi: 10.1159/000435881. Epub 2015 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 26227563]

Benhamou J, Gensburger D, Messiaen C, Chapurlat R. Prognostic Factors From an Epidemiologic Evaluation of Fibrous Dysplasia of Bone in a Modern Cohort: The FRANCEDYS Study. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2016 Dec:31(12):2167-2172. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2894. Epub 2016 Jul 13 [PubMed PMID: 27340799]