Introduction

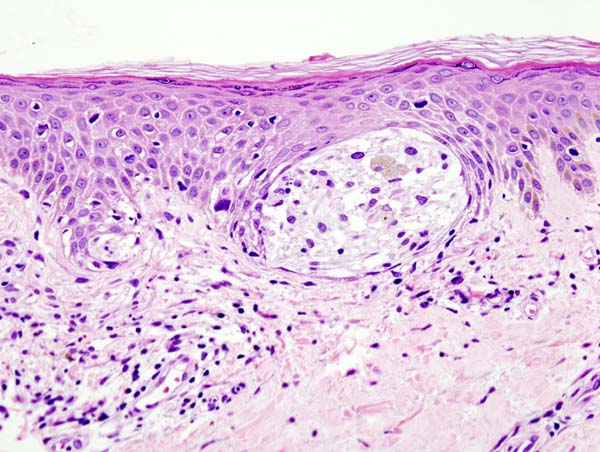

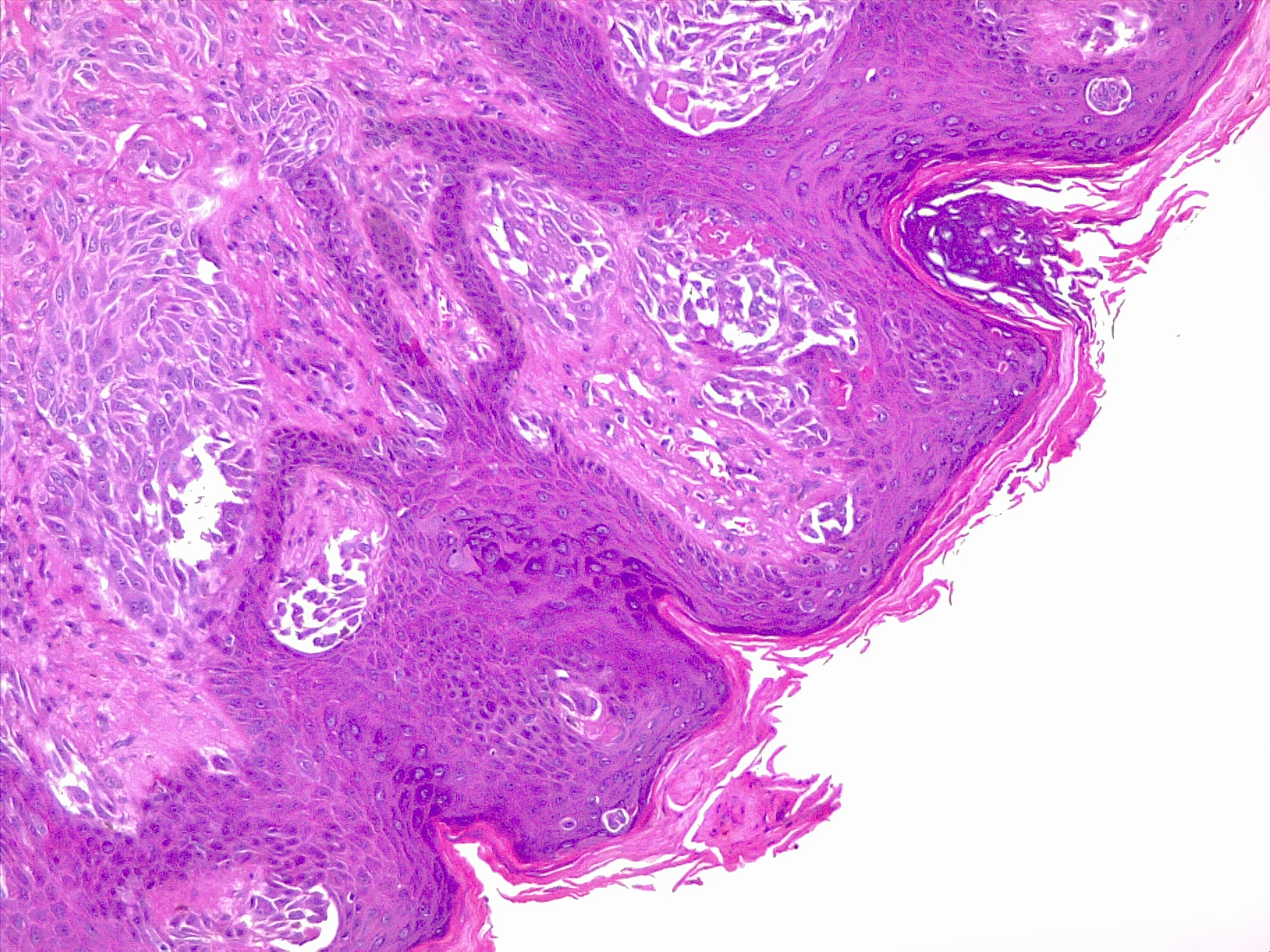

Melanoma is a type of skin cancer involving melanocytes—the pigment cells responsible for the skin's tan color that resurface to the topmost skin layer (see Image. Malignant Melanoma of the Skin). These cells provide an evolutionary benefit by protecting skin DNA from ultraviolet (UV) radiation and exposure. The accumulation of DNA mutations, most often secondary to UV light radiation from excessive sun exposure, contributes to the melanocyte's loss of division inhibition.[1] A thorough understanding of the histopathological features of melanoma is crucial for comprehending the biology of the tumor, thereby leading to a more precise treatment decision.

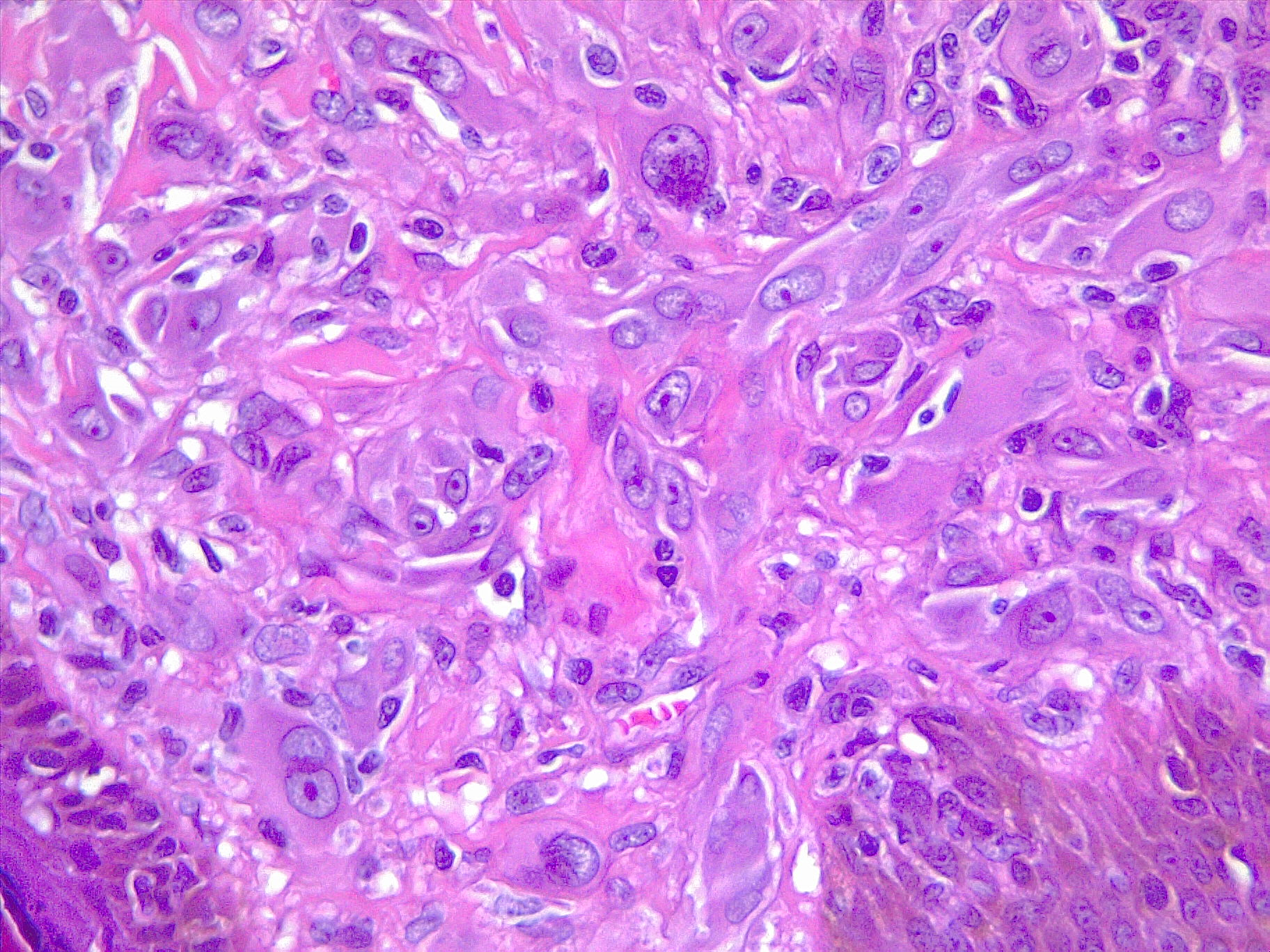

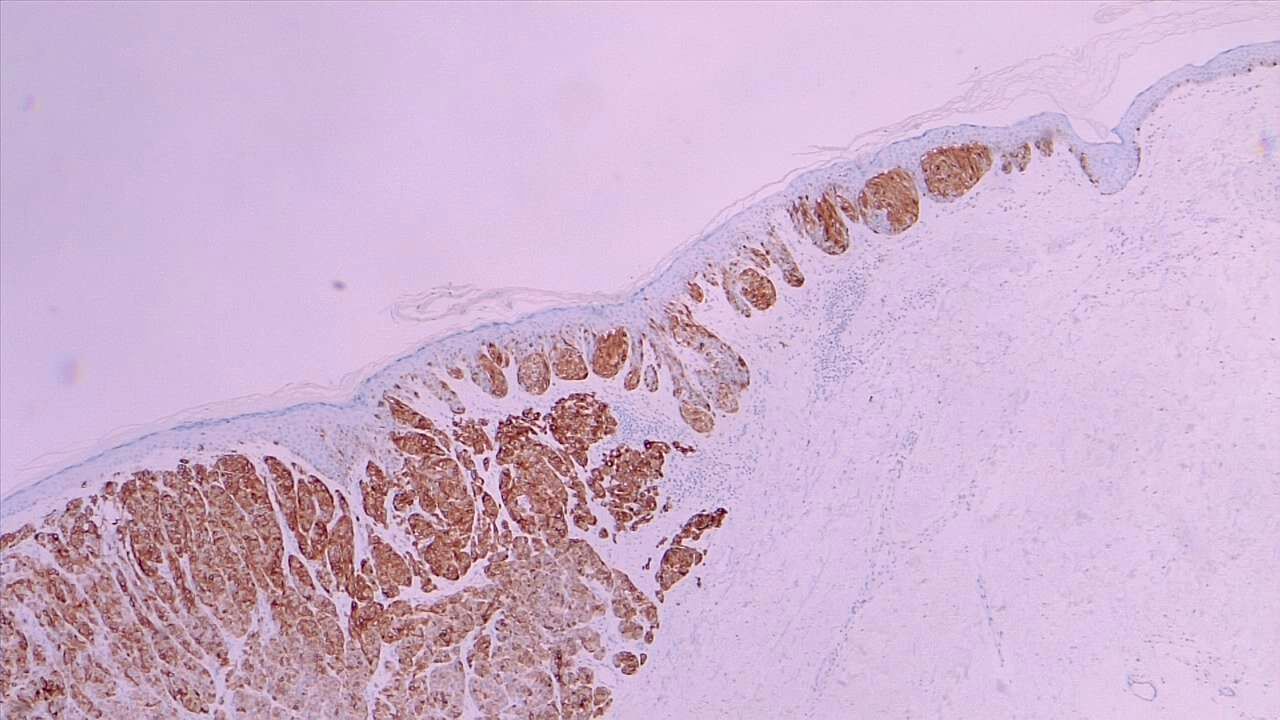

Histologically, melanoma lesions are characterized by their architectural and cytological features. Architectural features include asymmetry, irregular borders, and variable coloration. Cytological features include cellular pleomorphism, nuclear atypia, presence or absence of ulceration, and mitotic activity.[2] Immunohistochemical stains, such as S100, Melan-A, and human melanoma black-45 (HMB-45), aid in confirming melanocytic differentiation and distinguishing melanoma from other tumors.[3] Breslow depth and Clark level are crucial histological prognostic indicators for melanoma.

Melanoma exhibits molecular heterogeneity, resulting in various subtypes with distinct clinical behaviors and therapeutic responses. The main subtypes include superficial spreading melanoma, nodular melanoma, lentigo maligna melanoma, and acral lentiginous melanoma, each characterized by unique clinical and histopathological features[4]. See Image. Malignant Melanoma. Understanding these subtypes is essential for accurate diagnosis, prognostication, and treatment.

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

Frozen Section Analysis of Melanoma Pathology

Frozen section analysis is generally not recommended for evaluating melanoma margins due to several significant limitations. The histology of melanoma can be complex, and distinguishing it from normal cells is particularly challenging when using this technique. This method can create tissue artifacts and distort cellular details, leading to inaccuracies and a higher likelihood of false negatives or positives compared to traditional paraffin-embedded sections.[5]

Accurate margin assessment is crucial to ensure complete excision and reduce recurrence risk, necessitating more precise methods. In addition, definitive melanoma diagnosis often requires special stains and immunohistochemical techniques that are not feasible with frozen sections. Given the tumor's heterogeneity, a thorough examination of the entire surgical specimen is essential, best achieved through paraffin embedding.[6] Therefore, permanent sections from paraffin-embedded tissue provide a detailed and reliable assessment for effective melanoma treatment planning.

Mohs Surgery

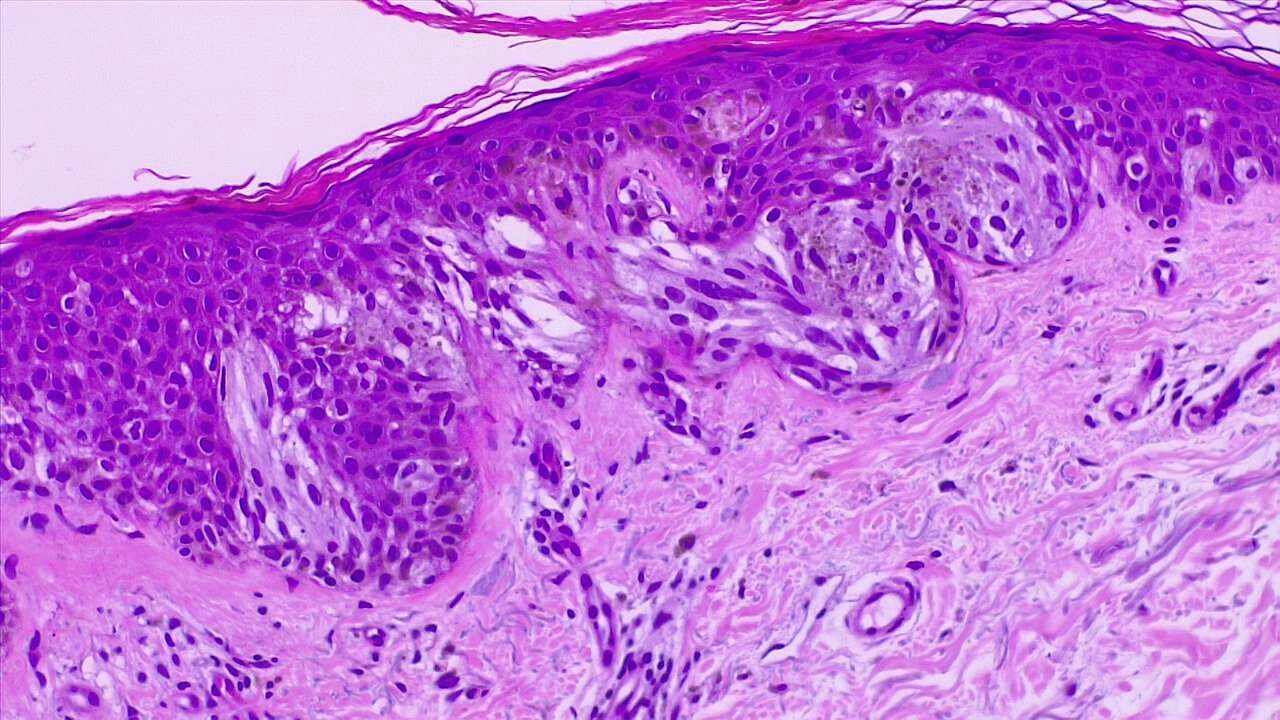

Mohs micrographic surgery is primarily used for basal and squamous cell carcinoma but can also be employed for melanoma under specific circumstances. This surgery is indicated for melanoma primarily when precision in margin control is crucial, such as in melanoma in situ, including lentigo maligna; superficial spreading melanoma; and desmoplastic melanoma. These types often present with irregular and widespread margins, making traditional excision challenging. See Image. Melanoma In Situ (Right Field) and Malignant Melanoma With Dermal Invasion.

Mohs surgery is particularly beneficial for melanoma tumors in cosmetically and functionally sensitive areas such as the face, ears, and genitals, where tissue conservation is critical. The technique may also be used for acral lentiginous melanoma on the palms, soles, and under the nails, and recurrent melanoma lesions to ensure complete removal and minimize healthy tissue loss.[7] The process includes detailed mapping, freezing, sectioning, and staining of the tissue to detect cancer cells accurately. However, Mohs surgery is generally less preferred for invasive melanoma due to the complex staining required to identify melanoma cells accurately. In such cases, traditional wide local excision is often recommended to ensure comprehensive removal of the cancerous tissue.[8]

Clinical Significance

Melanoma Diagnosis and Histopathological Examination

Various biopsy techniques are used to establish a pathological diagnosis of melanoma, each tailored to specific clinical scenarios and diagnostic requirements (see Image. Spitz Melanoma of the Skin). According to the 2024 National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines for Cutaneous Melanoma (NCCN Cutaneous Melanoma), the following considerations and techniques are recommended for optimal diagnosis and subsequent management:

- Excisional or complete biopsy: Excisional biopsy with 1- to 3-mm margins is preferred, using techniques such as saucerization or deep shave removal, punch biopsy for small-diameter lesions, or elliptical excision. Wider margins must be avoided for accurate subsequent lymphatic mapping.

- Orientation of biopsy: The orientation should be planned with definitive wide local excision in mind for elliptical or fusiform excisional biopsies. The incision may be oriented longitudinally (axially) and parallel to the underlying lymphatics on the extremities.

- Incisional or punch biopsy: Full-thickness incisional or punch biopsy of the clinically thickest or most atypical portion of the lesion is acceptable, especially in certain anatomical areas, such as palm, sole, digit, face, and ear, or for extensive lesions. Multiple scouting biopsies can assist in managing extensive lesions.[9]

- Shave biopsy: A superficial or tangential shave biopsy may compromise pathological diagnosis and complete assessment of Breslow thickness but is acceptable when the index of suspicion is low. However, a broad shave biopsy may be optimal for histologically evaluating melanoma in situ, particularly for lentigo maligna-type melanoma.

- Additional biopsy considerations: If a shave removal or tangential shave biopsy shows a residual tumor or pigment at the base, a deeper biopsy, such as punch or elliptical, should be performed immediately and submitted separately to the pathologist. A nail matrix biopsy should be performed if subungual melanoma is suspected, requiring expertise in the biopsy of the nail apparatus.

- Repeat biopsy: Repeat narrow-margin excisional biopsy is generally not indicated if the initial specimen meets the sentinel lymph node biopsy criteria unless the initial biopsy is inadequate for diagnosis or microstaging.

Histopathological examination of biopsy specimens is paramount for confirming the diagnosis of melanoma and providing crucial information for subsequent management. Pathologists experienced in melanocytic neoplasms should report the biopsy, utilizing appropriate immunohistochemical stains and molecular testing for histologically equivocal lesions. Essential elements to be reported include Breslow thickness, ulceration, microsatellites, margin status, dermal mitotic rate, lymphovascular or angiolymphatic invasion, histologic subtype, regression, and neurotropism. Synoptic reporting containing this information is strongly recommended for optimal patient care.

Histopathological Diagnosis

Histopathological examination of biopsy specimens plays a crucial role in confirming the diagnosis of melanoma and providing essential information for treatment planning and prognosis. The biopsy should be reported by a pathologist or a dermatopathologist experienced in melanocytic neoplasms. Appropriate immunohistochemical stains may aid in histopathologic diagnosis. Molecular testing should be considered for evaluating histologically equivocal lesions and rendering an expert dermatopathology review. Minimal elements to be reported should include factors that inform pathologic T stage: Breslow thickness (reported to the nearest 0.1 mm) and ulceration (whether present or absent).

Histological subtype: Melanoma has various histological subtypes, each with distinct characteristics and behaviors. Histopathological examination allows pathologists to specify the melanoma subtype in the biopsy specimen. Common subtypes include superficial spreading melanoma, nodular melanoma, lentigo maligna melanoma, acral lentiginous melanoma, and desmoplastic melanoma. Recognizing the subtype is essential as it may influence treatment decisions and prognosis.

Breslow thickness: Breslow thickness, named after Alexander Breslow, is a measurement that determines the depth of melanoma invasion into the skin. Introduced in 1970, Breslow thickness revolutionized melanoma prognosis by providing a quantitative measure of tumor thickness (reported to the nearest 0.1 mm), correlating with the risk of metastasis and overall prognosis. Thicker tumors are associated with poorer outcomes, whereas thinner tumors generally have a better prognosis. The histopathological examination allows for accurate measurement of Breslow thickness, guiding staging and treatment decisions.

Clark level of invasion: The Clark level of invasion, developed by Wallace H. Clark Jr. in 1969, categorizes melanoma lesions based on their depth of penetration into the layers of the skin. Clark proposed 5 levels of invasion, ranging from level I, confined to the epidermis, to level V, invasion into the subcutaneous tissue. Each level represents a deeper invasion into the skin layers, with higher levels associated with a greater risk of metastasis and poorer outcomes. Histopathological examination allows pathologists to determine the Clark level accurately, aiding in staging and treatment planning.

Immunohistochemical staining: Immunohistochemical staining is a valuable tool used in conjunction with histopathological examination in diagnosing melanoma. These specialized stains target specific proteins expressed by melanocytes, aiding in distinguishing melanoma cells from benign nevi and other cutaneous malignancies. Common melanocytic markers include S-100 protein, HMB-45, and Melan-A, also known as MART-1. Positive staining for these markers supports the diagnosis of melanoma and helps differentiate it from other skin lesions.

Lymphovascular or perineural invasion: The presence of lymphovascular or perineural invasion should be noted in pathology reports as they carry prognostic significance and may influence treatment decisions. Typically, the presence of either suggests a poorer prognosis, as the invasion extends into the nerves or lymphatics.

Neurotropism: Pathology reporting of neurotropism—whether present, absent, or indeterminate—may help guide clinical decision-making, such as performing further excision or adjuvant radiation therapy.

Microsatellites: If microsatellites are observed on initial biopsy or subsequent wide excision, they should be reported. The presence of microsatellites in the specimen upstages the patient to stage III melanoma.

Margin status: Margin status, indicating involvement of both deep and peripheral margins, should be reported on all biopsies and excisions.

Synoptic reporting: Synoptic reporting containing the following information is strongly recommended for optimal patient care:

- Presence of macroscopic satellite lesions in the gross tumor specimen, if clinically evident

- Dermal mitotic rate per mm2

- Lymphovascular or angiolymphatic invasion

- Histological subtype (if desmoplastic, specify if pure or mixed)

Notation of lentigo maligna or high cumulative sun damage subtype: Notation of lentigo maligna or high cumulative sun damage subtype may affect surgical or other treatment approaches, regression (if >75% or extending beneath measured Breslow thickness), and neurotropism (including peritumoral or intratumoral) or perineural invasion. If a residual invasive melanoma is evident in the wide excision specimen, the pathologist should incorporate elements of the initial biopsy and wide excision, such as thickest tumor depth and ulceration, to arrive at a final pathological T stage.

Growth Phases of Melanoma

Melanoma progresses through 4 main growth phases as follows:

- Radial growth phase: In this phase, melanoma cells are confined to the epidermis and spread in a radial pattern. Depending on tumor aggressiveness, this phase may last months to several years.

- Vertical growth phase: The tumor begins to penetrate below the epidermis and grow deeper, marking the point at which the melanoma becomes invasive.

- Tumor thickness: During this stage, melanoma grows deeper and thicker. Thickness is a significant prognostic indicator and is most commonly measured in millimeters.

- Metastatic: The melanoma invades subdermal lymphatics and blood vessels, such as capillaries, and has seeded systemically into the circulation. Metastases may localize to regional lymph nodes or spread distantly to other organs.[10]

The 2018 Evolutionary Pathway Classification of Melanoma

The 2018 Evolutionary Pathway Classification of Melanoma, introduced by Long et al, provides a framework for understanding the molecular and genetic heterogeneity of melanoma tumors and their progression.[11] This classification system categorizes melanoma tumors into 4 distinct evolutionary pathways based on the following genetic alterations and evolutionary trajectories:

- BRAF-mutant pathway: This pathway is characterized by mutations in the BRAF gene, particularly the V600E mutation, leading to constitutive activation of the MAPK signaling pathway. BRAF-mutant melanoma tumors often exhibit high levels of genomic instability and are associated with chronic sun exposure. Tumors tend to have a high mutation burden but are responsive to BRAF and MEK inhibitors.[12]

- NRAS-mutant pathway: Melanoma tumors in this pathway harbor mutations in the NRAS gene, resulting in constitutive activation of the MAPK pathway similar to BRAF-mutant melanoma tumors. NRAS-mutant melanoma lesions are typically associated with chronically sun-damaged skin and have a moderate mutation burden. The tumors are less responsive to BRAF inhibitors but may improve with MEK inhibitors and immunotherapy.

- NF1-mutant pathway: This pathway involves mutations in the NF1 gene, negatively regulating the RAS signaling pathway. NF1-mutant melanoma lesions often exhibit genomic stability and a low mutation burden. The tumors are associated with chronically sun-damaged skin and have a distinct gene expression profile. NF1-mutant melanoma tumors are less responsive to targeted therapies but may respond to immunotherapy.

- Triple-wild-type pathway: Melanoma lesions in this pathway lack mutations in BRAF, NRAS, and NF1 genes and are characterized by diverse genetic alterations. Triple-wild-type melanoma tumors often arise on nonchronically sun-exposed skin and exhibit high levels of UV-induced mutagenesis. The lesions have a high mutation burden and may respond to immunotherapy, although targeted therapies are generally ineffective.[13]

The Evolutionary Pathway Classification of Melanoma provides insights into the molecular mechanisms driving melanoma development and progression and guides treatment strategies tailored to the specific genetic alterations present in individual tumors.

Morphologic Classification of Melanoma

- Superficial spreading melanoma: Superficial spreading melanoma is characterized by its radial growth phase, which spreads horizontally across the skin surface before transitioning to a vertical growth phase. This subtype typically presents as irregularly pigmented macules or patches with asymmetrical borders. See Image. Malignant Melanoma, Superficial Spread.

- Nodular melanoma: Nodular melanoma is known for its rapid vertical growth phase, often lacking an extensive radial growth phase. This tumor typically presents as a raised nodule with uniform coloration, although it may also manifest as a polypoid- or dome-shaped lesion.

- Lentigo maligna melanoma: This subtype arises from lentigo maligna, a precursor lesion that develops over years or decades on sun-exposed skin. Lentigo maligna melanoma lesions are broad, flat, tan-brown patches with irregular borders, often displaying areas of color variation and asymmetric pigmentation.

- Acral lentiginous melanoma: Acral lentiginous melanoma primarily affects acral surfaces, such as the palms, soles, and nail beds. This subtype typically presents as irregularly pigmented macules or patches, sometimes resembling lentigo maligna but occurring on non–hair–bearing skin.

- Desmoplastic melanoma: This rare subtype is characterized by a fibrous stromal reaction that often resembles scar tissue. Desmoplastic melanoma tends to occur in older individuals and presents as firm, flesh-colored, or pink nodules with poorly defined borders.

- Amelanotic melanoma: This subtype lacks typical melanin pigmentation, making it challenging to diagnose clinically. Amelanotic melanoma lesions may appear as pink, red, or flesh-colored nodules or plaques, often delaying diagnosis and treatment due to their mimicry of other skin lesions.

- Mucosal melanoma: These tumors arise from melanocytes in mucosal surfaces, such as the oral cavity, nasal cavity, genitalia, and anorectal region. The lesions may be pigmented or nonpigmented, often diagnosed at a more advanced stage due to their hidden location.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The accurate diagnosis and management of melanoma require a high level of expertise across various health disciplines. Physicians, advanced practitioners, and dermatologists must be proficient in a range of biopsy techniques, including excisional, incisional, punch, and shave biopsies, to secure precise samples for histopathological examination. Pathologists and dermatopathologists require specialized skills to analyze and interpret these biopsy specimens, employing immunohistochemical stains and molecular testing when necessary. Furthermore, nurses and advanced practitioners must possess the clinical acumen to assess patients effectively, monitor skin changes, and identify suspicious lesions warranting biopsy.

Adherence to the current national guidelines for biopsy techniques ensures standardized care, facilitating accurate melanoma diagnosis. An interprofessional approach is crucial, involving coordinated care among dermatologists, oncologists, surgeons, pathologists, and primary care providers to develop comprehensive management plans. Early detection and continuous monitoring are strategic imperatives, particularly for high-risk patients, underscoring the need for robust screening programs and regular skin evaluations.

Ethical Considerations and Responsibilities

Ethical practice in diagnosing and treating melanoma involves obtaining informed consent and ensuring that patients are fully aware of biopsy procedures, associated risks, benefits, and potential outcomes. Maintaining patient privacy and confidentiality throughout the diagnostic and treatment processes is paramount. Equitable care provision is essential, guaranteeing high-quality melanoma care accessibility regardless of patients' socioeconomic status, thus promoting equity in diagnosis and treatment.

Physicians and pathologists are responsible play a crucial role in diagnosing melanoma accurately, which is pivotal for appropriate treatment planning.[14] Patient education, encompassing melanoma risks, preventive measures, and the importance of early detection, should be a concerted effort by all healthcare professionals. Coordinating follow-up care is crucial to monitor for recurrence or metastasis, necessitating timely appointments and comprehensive care plans.

Interprofessional Communication and Care Coordination

Enhancing patient-centered care involves regular interdisciplinary team meetings to discuss patient cases, ensuring comprehensive attention to all care aspects. Shared decision-making with patients, involving them in their care decisions and respecting their preferences and values, is crucial. Effective communication between primary care providers and specialists ensures timely referrals and diagnoses, which is integral to improving patient outcomes.[15]

Developing and implementing integrated care plans that engage all relevant healthcare professionals ensure continuity of care. Clear and thorough documentation of biopsy results, treatment plans, and patient interactions is essential to prevent errors and ensure patient safety. Continuous monitoring of patient progress and prompt reporting of adverse events or complications are critical components of patient safety protocols.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Greene A, Kunesh J. 2024 update on referrals to dermatologists for full-skin examinations and future considerations. International journal of dermatology. 2024 Jun 2:():. doi: 10.1111/ijd.17276. Epub 2024 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 38825726]

Strahan AG, Švagelj I, Jukic D. Relationship of Histopathologic Parameters and Gene Expression Profiling in Malignant Melanoma. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2024 Jan:25(1):119-126. doi: 10.1007/s40257-023-00815-2. Epub 2023 Sep 4 [PubMed PMID: 37667131]

Elgash M, Young J, White K, Leitenberger J, Bar A. An Update and Review of Clinical Outcomes Using Immunohistochemical Stains in Mohs Micrographic Surgery for Melanoma. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2024 Jan 1:50(1):9-15. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000003945. Epub 2023 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 37738278]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTas F, Erturk K. Major Histotypes in Skin Melanoma: Nodular and Acral Lentiginous Melanomas Are Poor Prognostic Factors for Relapse and Survival. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2022 Nov 1:44(11):799-805. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000002264. Epub 2022 Jul 19 [PubMed PMID: 35925149]

Petitjean C, Bénateau H, Veyssière A, Morello R, Dompmartin A, Garmi R. Interest of frozen section procedure in skin tumors other than melanoma. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2023 Sep:84():377-384. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2023.06.030. Epub 2023 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 37393761]

Young JN, Nguyen TA, Freeman SC, Hill E, Johnson M, Gharavi N, Bar A, Leitenberger J. Permanent section margin concordance after Mohs micrographic surgery with immunohistochemistry for invasive melanoma and melanoma in situ: A retrospective dual-center analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2023 May:88(5):1060-1065. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.01.019. Epub 2023 Jan 30 [PubMed PMID: 36720365]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWilliams GJ, Quinn T, Lo S, Guitera P, Scolyer RA, Thompson JF, Ch'ng S. Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of invasive melanoma: A systematic review with meta-analyses. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2024 Jun 6:():. doi: 10.1111/jdv.20138. Epub 2024 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 38842170]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMansilla-Polo M, Morgado-Carrasco D, Toll A. Review on the Role of Paraffin-embedded Margin-controlled Mohs Micrographic Surgery to Treat Skin Tumors. Actas dermo-sifiliograficas. 2024 Jun:115(6):T555-T571. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2024.04.019. Epub 2024 Apr 21 [PubMed PMID: 38648936]

Kottner J, Fastner A, Lintzeri DA, Blume-Peytavi U, Griffiths CEM. Skin health of community-living older people: a scoping review. Archives of dermatological research. 2024 Jun 1:316(6):319. doi: 10.1007/s00403-024-03059-0. Epub 2024 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 38822889]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDe Giorgi V, Silvestri F, Cecchi G, Venturi F, Zuccaro B, Perillo G, Cosso F, Maio V, Simi S, Antonini P, Pillozzi S, Antonuzzo L, Massi D, Doni L. Dermoscopy as a Tool for Identifying Potentially Metastatic Thin Melanoma: A Clinical-Dermoscopic and Histopathological Case-Control Study. Cancers. 2024 Apr 1:16(7):. doi: 10.3390/cancers16071394. Epub 2024 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 38611072]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceElder DE, Bastian BC, Cree IA, Massi D, Scolyer RA. The 2018 World Health Organization Classification of Cutaneous, Mucosal, and Uveal Melanoma: Detailed Analysis of 9 Distinct Subtypes Defined by Their Evolutionary Pathway. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2020 Apr:144(4):500-522. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2019-0561-RA. Epub 2020 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 32057276]

Wen X, Han M, Hosoya M, Toshima R, Onishi M, Fujii T, Yamaguchi S, Kato S. Identification of BRAF Inhibitor Resistance-associated lncRNAs Using Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 Transcriptional Activation Screening. Anticancer research. 2024 Jun:44(6):2349-2358. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.17042. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38821628]

Haugh AM, Osorio RC, Francois RA, Tawil ME, Tsai KK, Tetzlaff M, Daud A, Vasudevan HN. Targeted DNA Sequencing of Cutaneous Melanoma Identifies Prognostic and Predictive Alterations. Cancers. 2024 Mar 29:16(7):. doi: 10.3390/cancers16071347. Epub 2024 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 38611025]

Shah P, Trepanowski N, Grant-Kels JM, LeBoeuf M. Mohs micrographic surgery in the surgical treatment paradigm of melanoma in situ and invasive melanoma: A clinical review of treatment efficacy and ongoing controversies. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2024 May 19:():. pii: S0190-9622(24)00756-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2024.05.024. Epub 2024 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 38768857]

Hoier D, Groß-Ophoff-Müller C, Franklin C, Hallek M, von Stebut E, Elter T, Mauch C, Kreuzberg N, Koll P. Digital decision support for structural improvement of melanoma tumor boards: using standard cases to optimize workflow. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology. 2024 Mar 8:150(3):115. doi: 10.1007/s00432-024-05627-3. Epub 2024 Mar 8 [PubMed PMID: 38457085]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence