Introduction

Methemoglobinemia is a condition with life-threatening potential in which diminution of the oxygen-carrying capacity of circulating hemoglobin occurs due to conversion of some or all of the four iron species from the reduced ferrous [Fe2+] state to the oxidized ferric [Fe3+] state. Ferric iron is unable to bind and transport oxygen. Increased levels of methemoglobin results in functional anemia.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Methemoglobinemia can result from either congenital or acquired processes. Congenital forms of methemoglobinemia are due to autosomal recessive defects in the enzyme cytochrome b5 reductase (CYB5R) or due to autosomal dominant mutations in the genes that code for globin proteins collectively known as hemoglobins M.[1] Multiple variants of hemoglobin M have been described (Boston, Fort Ripley, Hyde Park, Iwate, Kankakee, Osaka, Saskatoon).[2] Congenital methemoglobinemia type I is the condition where the CYB5R defect is expressed only on erythrocytes. Congenital methemoglobinemia type II occurs when all cells express the defect.[3] Hemoglobin M disease is a collection of possible mutations that usually occur in the alpha or beta chains of hemoglobin near the heme iron.[4] The mutation leads to easier oxidation of the iron to the ferric [Fe3+] state.[5] Acquired methemoglobinemia, which is much more common, is the result of exposure to substances that cause oxidation of the hemoglobin either directly or indirectly. This exposure results in the production of methemoglobin that exceeds the body’s capacity to convert the iron within the hemoglobin back to its ferrous state. Acquired methemoglobinemia may be due to exposure to direct oxidizing agents (e.g. benzocaine and prilocaine), indirect oxidation (e.g. nitrates), or metabolic activation (e.g. aniline and dapsone).[6] Classic examples include patient exposure to benzocaine in endoscopy suite and infantile exposure to nitrites from well water.

Epidemiology

Congenital methemoglobinemia due to cytochrome b5 reductase deficiency is very rare, but the actual incidence is not known. Increased frequency of disease has been found in Siberian Yakuts, Athabaskans, Eskimos, and Navajo.[7] Acquired methemoglobinemia is much more frequently encountered than the congenital form; although, it is also an unusual occurrence. Most cases are due to inadvertent exposure to a chemical or through the use of topical or local anesthetics. A single center review of nearly 30,000 transesophageal echocardiograms found the incidence of methemoglobinemia to be 0.067%.[8] A systematic review of cases of local anesthetic-related methemoglobinemia found that benzocaine was an agent in two-thirds of cases.[9] This higher association with benzocaine-containing products has led the United States Food and Drug Administration to release multiple advisories regarding the use of benzocaine-containing oral products.[10]

Pathophysiology

Methemoglobin forms when hemoglobin is oxidized to contain iron in the ferric [Fe3+] rather than the normal ferrous [Fe2+] state. Any of the four iron species within a hemoglobin molecule that are in the ferric form are unable to bind oxygen. The presence of iron in the ferric [Fe3+] state results in allosteric changes to the molecule that shifts the oxygen-dissociation curve to the left. This shift leads to increased affinity of the ferrous iron for oxygen and thus impaired oxygen release to the tissue.[11] The end result of these changes is decreased oxygen delivery leading to tissue hypoxia.

In Hemoglobin M disease, a mutation in the gene coding for one of the globin proteins usually results in the substitution of an amino acid with tyrosine. This mutation allows for the stabilization of iron in the ferric [Fe3+] state. Patients with Hemoglobin M disease usually have methemoglobin levels between 15-30% and remain asymptomatic.[1]

Under normal circumstances, a small amount of iron oxidizes to the ferric [Fe3+] state during the routine delivery of oxygen to tissue. Maintenance of methemoglobin levels is usually below 1% through the action of the enzyme cytochrome-b5 reductase. Cytochrome-b5 reductase utilizes NADH formed during glycolysis to reduce methemoglobin back to functional hemoglobin.[12]

An alternate pathway for the reduction of methemoglobin is through the function of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate hydrogen methemoglobin (NADPH-MetHb) reductase. NADPH-MetHb reductase utilizes NADPH that forms through the action of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) in the hexose monophosphate shunt, for its reducing power.[1] Under normal physiologic circumstances, NADPH-MetHb reductase contributes very little to the reduction of methemoglobin, but under oxidative stress, the function of this alternative reduction pathway can be enhanced by the presence of exogenous electron donors, such as methylene blue. This association with G6PD often leads to confusion that G6PD deficiency, itself, is a risk factor for methemoglobinemia.

Toxicokinetics

Methemoglobinemia secondary to toxic exposures occurs when cytochrome-b5 reductase's ability to reduce ferric hemoglobin, or methemoglobin, is overwhelmed by the induced oxidant stress. The result is increasing concentrations of methemoglobin leading to methemoglobinemia.

History and Physical

Methemoglobinemia should be considered in the setting of dyspnea or cyanosis and hypoxemia that is refractory to supplemental oxygen, especially in the setting of exposure to a known oxidative agent. However, the presentation may vary in severity from minimally symptomatic to severe. The clinical presentation of methemoglobinemia is based on a spectrum illness that is associated with cyanosis, pallor, fatigue, weakness, headache, central nervous system depression, metabolic acidosis, seizures, dysrhythmias, coma, and death. The degree of symptom severity is multifactorial and depends on the patient's percentage of methemoglobin, the rate at which methemoglobin was accumulated, the individual's ability to intrinsically clear it, and the underlying health status of the patient. Duration and magnitude of exposure to an oxidizing agent may also play a role.

Methemoglobin is expressed as a concentration or a percentage and this is further described under evaluation. Percentage of methemoglobin is calculated by dividing the concentration of methemoglobin by the concentration of total hemoglobin. Percentage of methemoglobin is likely a better indicator of illness severity than overall concentration, as underlying medical conditions play an important role. For example, a methemoglobin concentration of 1.5 g/dL may represent a percentage of 10% in an otherwise healthy patient with a baseline hemoglobin of 15 mg/dL, whereas the presence of the same concentration of 1.5 g/dL of methemoglobin in an anemic patient with a baseline hemoglobin of 8 g/dL would represent a percentage of 18.75%. The former patient will be left with a functional hemoglobin concentration of 13.5 g/dL and potentially remain asymptomatic while the latter patient with a functional hemoglobin concentration 6.5 g/dL may be severely symptomatic with a methemoglobin of less than 20%. This may be further compounded by the "functional hemoglobin's" decreased ability to release oxygen in the presence of methemoglobin. Anemia, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and essentially any pathology that impairs the ability to deliver oxygen may worsen the symptoms of methemoglobinemia.

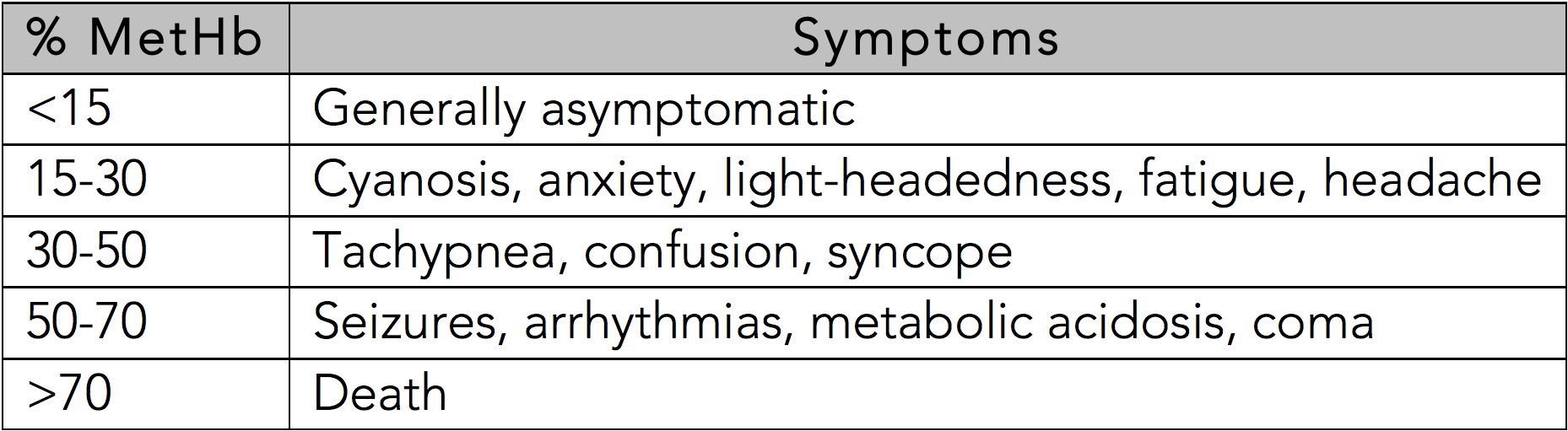

In the otherwise healthy person, cyanosis may be clinically evident with a methemoglobin as low as 10%.[11] The classic appearance of "chocolate brown blood" can be present at as low as 15%. As the percentage of methemoglobinemia approaches 20%, the patient may experience anxiety, light-headedness, and headaches. At methemoglobin levels of 30-50%, there may be tachypnea, confusion, and loss of consciousness. Approaching 50%, the patient is at risk for seizures, dysrhythmias, metabolic acidosis, and coma. Levels above 70% are often fatal.[13]

See Table 1: Symptoms Based on Methemoglobin Level

Evaluation

Methemoglobinemia is a clinical diagnosis based on history and presenting symptoms, including hypoxemia refractory to supplemental oxygen and the likely presence of chocolate-colored blood. The diagnosis is confirmed by arterial or venous blood gas with co-oximetry, which will speciate hemoglobin to determine the methemoglobin concentration and percentage.[10] SpO2 measurements cannot be utilized to directly calculate the severity of methemoglobinemia.

"Refractory hypoxemia" is a significant diagnostic clue. This is generally evident on pulse oximetry measurements of oxygen saturation (SpO2) based on wavelength detection, but not when calculated from blood gas analysis using the partial pressure of oxygen in the blood (SaO2). Traditional dual wave-length pulse oximetry is inaccurate in the setting of methemoglobinemia because these pulse oximeters measure the absorbance of light at two wavelengths - 660 and 940 nm. The ratio of this absorbance allows the distinction between oxyhemoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin, with the expressed percentage, or SpO2, indicating the measured amount of hemoglobin that is oxygenated. Methemoglobin has high absorbance at both of these wavelengths, leading to the interference that causes an inaccurate SpO2 reading. When the level of methemoglobin approaches 30-35%, the ratio of absorbance becomes 1.0. A ratio of absorbance (A660/A940) of 1.0 reads as a SpO2 of 85%.[14] There is a disproportional, inverse relationship between methemoglobin concentration and SpO2, and despite SpO2 being consistently depressed, it is generally a falsely elevated indication of true oxygen saturation that varies depending on a specific device.

Whereas SpO2 measurements are inaccurate and depressed from wavelength interference, often to 75-90% even with supplemental oxygen, SaO2 calculations are falsely normal due to the assumption that all hemoglobin is either oxyhemoglobin or deoxyhemoglobin.[10] The difference between the depressed SpO2 measurement and the falsely normal SaO2 calculation is known as the "saturation gap." This additional diagnostic clue should hint at the presence of a hemoglobinopathy, but is nonspecific and cannot be used to confirm a diagnosis of methemoglobinemia. A saturation gap greater than 5% presents in cases of elevated abnormal forms of hemoglobin such as carboxyhemoglobin, methemoglobin, and sulfhemoglobin.[15]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of methemoglobinemia includes removal of the inciting agent and consideration of treatment with the antidote, methylene blue (tetramethylthionine chloride). High flow oxygen delivered by non-rebreather mask increases oxygen delivery to tissues and enhances the natural degradation of methemoglobin.

Methylene blue usually works rapidly and effectively through its interaction with the aforementioned secondary pathway of methemoglobin reduction, where NADPH-MetHb reductase reduces methylene blue to leukomethylene blue using NADPH from the G6PD-dependent hexose monophosphate shunt. Leukomethylene blue then acts as an electron donor to reduce methemoglobin to hemoglobin. In cases of acquired methemoglobinemia, treatment with methylene blue should occur when methemoglobin exceeds 20-30%, or at lower levels, if the patient is symptomatic. Treatment decision should be made on clinical presentation and not withheld for confirmational laboratory values. The methylene blue dose is 1-2 mg/kg (0.1-0.2 mL/kg of 1% solution) intravenously over 5 minutes.[12] The dose can be repeated in 30-60 minutes if significant symptoms or levels remain above the treatment threshold.

Practitioners should be aware of the side effect profile of methylene blue. Benign side effects include green or blue discoloration of urine and patients should be forewarned. Significant side effects are based on methylene blue, itself, being an oxidizing agent and an inhibitor of monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A). As an oxidizing agent, methylene blue can actually precipitate methemoglobinemia or hemolysis in high doses or when ineffectively reduced. Methylene blue administration in a patient taking a serotonergic agents may predispose to serotonin syndrome.[16] Caution should also be practiced with treating neonates as they are also very sensitive to oxidizing agents. Also, methylene blue is a United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) pregnancy category X drug, indicating that studies have shown concrete evidence of human fetal risk.

Although methylene blue administration is controversial in the setting of G6PD-deficiency due to reduced levels of NADPH, it is not contraindicated and should be administered cautiously and judiciously. Many G6PD deficient patients may have some level of G6PD that can still provoke an adequate response, and therefore, treatment should not be withheld. Doses of methylene blue observed to produce hemolysis in patients with G6PD deficiency has been observed to be over 5 mg/kg, which is more than twice the recommended dose.[17]

If methylene blue administration is ineffective after the second dose, underlying conditions including, but not limited to, G6PD and NADPH-MetHb reductase deficiency should be considered as reasons for refractoriness to treatment. However, methemoglobinemia alone is not an indication to screen for these disease processes.

When treatment with methylene blue is ineffective or not recommended, additional options may include ascorbic acid, exchange transfusion, hyperbaric oxygen therapy.[18][19] High-dose ascorbic acid (vitamin C), up to 10 g/dose intravenously, can be considered to treat methemoglobin. However, it is generally ineffective and not considered standard of care. High dose ascorbic acid administration is associated with increased urinary excretion of oxalate. In the presence of renal insufficiency, high dose ascorbic acid may be predisposed to renal failure due to hyperoxaluria.[20] (B3)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of cyanosis also includes:

- Anemia

- Asthma

- Congestive heart failure

- Cyanotic congenital heart disease

- Peripheral cyanosis

- Polycythemia

- Sulfhemoglobinemia

The differential diagnosis of bluish skin discoloration also includes:

- Acrodermatitis enteropathica

- Amiodarone-induced skin pigmentation

- Argyria

Prognosis

Most patients with methemoglobinemia respond well to treatment and can be discharged after brief period of observation. Anyone with persistent symptoms after initial treatment or exacerbated underlying medical conditions should be considered for admission.

Consultations

All cases of methemoglobinemia should be managed in consultation with a medical toxicologist.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Diagnosis of methemoglobinemia clinical and is confirmed by an arterial blood gas with co-oximetry

- Diagnostic clues are the presence of refractory hypoxemia, saturation gap, and chocolate-colored blood,

- Treatment with methylene blue should not be delayed for co-oximetry results.

- Methylene blue is a MAOI and, when administered to a patient taking any other serotonergic drug, can lead to serotonin syndrome.

- Methylene blue should be used cautiously and judiciously in infants and patients with G6PD-deficiency, but is not contraindicated.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

All cases should be managed in consultation a medical toxicologist. Critical care may be necessary in cases where prolonged treatment or observation are warranted, or if there have been significant adverse outcomes as a result of the elevated methemoglobin. For acquired methemoglobinemia, patients should receive education on how exposure to the offending agent led to the development of methemoglobinemia. The patient should be counseled to avoid future exposure.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Curry S. Methemoglobinemia. Annals of emergency medicine. 1982 Apr:11(4):214-21 [PubMed PMID: 7073040]

Haymond S, Cariappa R, Eby CS, Scott MG. Laboratory assessment of oxygenation in methemoglobinemia. Clinical chemistry. 2005 Feb:51(2):434-44 [PubMed PMID: 15514101]

Kedar PS, Gupta V, Warang P, Chiddarwar A, Madkaikar M. Novel mutation (R192C) in CYB5R3 gene causing NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase deficiency in eight Indian patients associated with autosomal recessive congenital methemoglobinemia type-I. Hematology (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2018 Sep:23(8):567-573. doi: 10.1080/10245332.2018.1444920. Epub 2018 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 29482478]

Percy MJ, Lappin TR. Recessive congenital methaemoglobinaemia: cytochrome b(5) reductase deficiency. British journal of haematology. 2008 May:141(3):298-308. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07017.x. Epub 2008 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 18318771]

Spears F, Banerjee A. Hemoglobin M variant and congenital methemoglobinemia: methylene blue will not be effective in the presence of hemoglobin M. Canadian journal of anaesthesia = Journal canadien d'anesthesie. 2008 Jun:55(6):391-2. doi: 10.1007/BF03021499. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18566207]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBradberry SM. Occupational methaemoglobinaemia. Mechanisms of production, features, diagnosis and management including the use of methylene blue. Toxicological reviews. 2003:22(1):13-27 [PubMed PMID: 14579544]

Burtseva TE, Ammosova TN, Protopopova NN, Yakovleva SY, Slobodchikova MP. Enzymopenic Congenital Methemoglobinemia in Children of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). Journal of pediatric hematology/oncology. 2017 Jan:39(1):42-45 [PubMed PMID: 27879543]

Kane GC, Hoehn SM, Behrenbeck TR, Mulvagh SL. Benzocaine-induced methemoglobinemia based on the Mayo Clinic experience from 28 478 transesophageal echocardiograms: incidence, outcomes, and predisposing factors. Archives of internal medicine. 2007 Oct 8:167(18):1977-82 [PubMed PMID: 17923598]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGuay J. Methemoglobinemia related to local anesthetics: a summary of 242 episodes. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2009 Mar:108(3):837-45. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318187c4b1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19224791]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNappe TM, Pacelli AM, Katz K. An Atypical Case of Methemoglobinemia due to Self-Administered Benzocaine. Case reports in emergency medicine. 2015:2015():670979. doi: 10.1155/2015/670979. Epub 2015 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 25874137]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWright RO, Lewander WJ, Woolf AD. Methemoglobinemia: etiology, pharmacology, and clinical management. Annals of emergency medicine. 1999 Nov:34(5):646-56 [PubMed PMID: 10533013]

Skold A, Cosco DL, Klein R. Methemoglobinemia: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Southern medical journal. 2011 Nov:104(11):757-61. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e318232139f. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22024786]

Wilkerson RG. Getting the blues at a rock concert: a case of severe methaemoglobinaemia. Emergency medicine Australasia : EMA. 2010 Oct:22(5):466-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2010.01336.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21040486]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChan ED, Chan MM, Chan MM. Pulse oximetry: understanding its basic principles facilitates appreciation of its limitations. Respiratory medicine. 2013 Jun:107(6):789-99. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.02.004. Epub 2013 Mar 13 [PubMed PMID: 23490227]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAkhtar J, Johnston BD, Krenzelok EP. Mind the gap. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2007 Aug:33(2):131-2 [PubMed PMID: 17692762]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRamsay RR, Dunford C, Gillman PK. Methylene blue and serotonin toxicity: inhibition of monoamine oxidase A (MAO A) confirms a theoretical prediction. British journal of pharmacology. 2007 Nov:152(6):946-51 [PubMed PMID: 17721552]

KELLERMEYER RW, TARLOV AR, BREWER GJ, CARSON PE, ALVING AS. Hemolytic effect of therapeutic drugs. Clinical considerations of the primaquine-type hemolysis. JAMA. 1962 May 5:180():388-94 [PubMed PMID: 14454972]

Grauman Neander N, Loner CA, Rotoli JM. The Acute Treatment of Methemoglobinemia in Pregnancy. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2018 May:54(5):685-689. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.01.038. Epub 2018 Apr 5 [PubMed PMID: 29627348]

Cho Y, Park SW, Han SK, Kim HB, Yeom SR. A Case of Methemoglobinemia Successfully Treated with Hyperbaric Oxygenation Monotherapy. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2017 Nov:53(5):685-687. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.04.036. Epub 2017 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 28838565]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLee KW, Park SY. High-dose vitamin C as treatment of methemoglobinemia. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2014 Aug:32(8):936. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.05.030. Epub 2014 May 24 [PubMed PMID: 24972962]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence