Introduction

Microscopic polyangiitis is a small vessel necrotizing vasculitis, a part of a large spectrum of disorders termed anti-neutrophil-cytoplasmic-antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitides (AAV). This umbrella term includes granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA or Churg-Strauss disease), and renal limited vasculitis (RLV). This classification of vasculitides based on the type of vessels involved and the underlying etiology was first laid down by the International Chapel Hill Convention Conference on the Nomenclature of Vasculitides (CHCC 2012).[1]

The term microscopic polyarteritis was introduced in the literature by Davson in 1948 to describe the pattern of glomerulonephritis seen in patients with polyarteritis nodosa. It was later described as a pattern of necrotizing vasculitis, without immune complex deposition, affecting small vessels such as the capillaries, venules, and arterioles. The disease commonly involves glomerulonephritis, pulmonary capillaritis, and other systemic capillary beds. It shows considerable overlap with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA). The absence of granulomatous inflammation involving the upper respiratory tract and the presence of pulmonary capillaritis is said to differentiate MPA from GPA. MPA has also been included in a group of disorders termed pulmonary-renal syndrome, which includes MPA, GPA, Goodpasture disease, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).[2][3]

Immunosuppressive medications are used to manage MPA. The choice of drugs depends partially on the rate of progression, the extent of the disease, and the degree of inflammation.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiopathogenesis of microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) and other related vasculitides have largely been attributed to anti-neutrophil-cytoplasmic antibodies or ANCA. These are host-derived auto-antibodies against shielded neutrophilic antigens. These antibodies react against primary granules present in neutrophils and monocytes. The formation of these antibodies has been hypothesized to be a two-step process.[4] The first step involves exposure of neutrophils to inflammatory cytokines leading to surface exposure of cryptogenic antigens like myeloperoxidase or MPO. Next, predisposing genetic, environmental, and other factors result in the production of MPO-ANCA. In the second step, these MPO-ANCA cause damage to the host vasculature by reacting and crosslinking neutrophils to the endothelial receptors.[5]

Only 70% of cases of MPA have ANCA at the time of diagnosis, and most of the cases of limited MPA do not have ANCA at all. This has led to the understanding that other factors may also play a role in its etiopathogenesis. These include, but are not limited to:

- Infectious Causes: There is considerable overlap in the clinical presentation of various infectious processes and MPA leading to this implication. A possible role of chronic nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus has been suggested in relapsing GPA as well.

- Drugs: Various drugs like hydralazine, thionamides, sulfasalazine, and minocycline, among others, have been observed to be associated with the incidence of ANCA-associated vasculitis.[6][7]

- Genetic Factors: More recently, a genome-wide study conducted in Europe reported genes like HLA-DP, HLA-DR3, and alpha-1 antitrypsin in the pathogenesis of ANCA-associated vasculitides.[8][7]

MPA has also been linked to the exposure of silica by inducing autoimmunity in patients with some genetic susceptibility.[9]

Epidemiology

Due to the recent differentiation of microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) from other AAVs, widespread data regarding its demographic factors in the American population is not available yet. One study conducted in Rochester, Minnesota, over a period of 20 years estimated the annual incidence of AAV to be 3.3 per 100,000 with a prevalence of 42.1 per 100,000. The incidence of GPA and MPA were approximately 1.5 per 100,000.[10] Studies from European countries have revealed a comparatively higher incidence and prevalence of AAV, with the highest incidence rates seen in Spain and the United Kingdom, 11.6 and 5.8 cases per million population, respectively.[11] There seems to be an increase in the prevalence of MPA in the last two decades, which may be attributed to, in part, the availability of ANCA testing.

Overall the incidence of MPA is more significant in southern Europe as opposed to northern Europe; for instance, the incidence in Norway is 2.7 per million but increases to 11.6 per million in Spain.[12] Other studies reveal that the frequency is not affected by latitude.[13][2]

Race

MPA is more common in the White than Black population.

Age

The median age of onset is 50 years.

Sex

The disease is more prevalent among males.

Pathophysiology

Microscopic polyangiitis is associated with MPO-ANCA in 58% of cases and with PR3-ANCA in 26% of cases.[14] However, a small number of patients are ANCA-negative.[15] Taken together, there is convincing evidence to suggest that MPO-ANCA is directly linked to the pathogenesis of MPA.[16]

As explained above, the clinical manifestations of MPA stem from the activation of primed neutrophils and MPO-ANCA with receptors present on the endothelial surface.[17] These lead to various manifestations affecting the renal, pulmonary, and other capillary beds. Individuals may present with an insidious onset of systemic signs like fever, malaise, or weight loss, but more commonly, the onset is acute in patients complaining of arthralgia and flu-like symptoms. MPA is a small vessel vasculitis it causes inflammation of the vessel walls. This may lead to necrosis and bleeding. MPA is characterized by pauci-immune, necrotizing, small vessel vasculitis without clinical or pathological evidence of granulomatous inflammation.

Renal manifestations are most common, and up to 80% to 100% of individuals have some form of glomerulonephritis at onset or with disease progression. The most common manifestation is a "pauci-immune" form of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN). Clinical presentation may vary from asymptomatic hematuria, sub-nephrotic proteinuria, a rise in serum creatinine, or overt renal failure. Pulmonary manifestations may be in the form of alveolar hemorrhage, which is sometimes the first presenting symptom of the disease.[18]

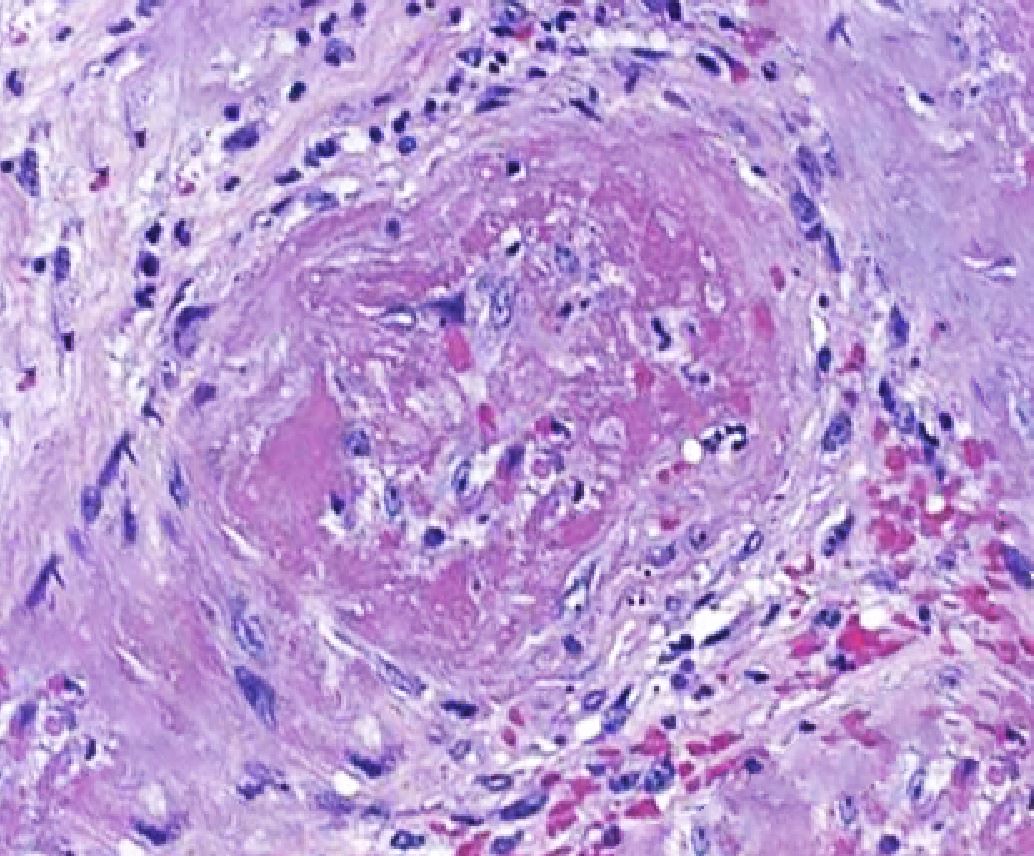

Histopathology

Histopathological evidence of vasculitis is the gold standard for confirmation of the diagnosis of microscopic polyangiitis and other AAV. The most commonly sampled tissues are renal, skin, and lung tissue. Pulmonary findings in MPA are most commonly a form of diffuse capillaritis (distinguishing it from GPA, which characteristically shows granulomatous lesions). Skin biopsy yields acute or chronic leukocytoclastic vasculitis with neutrophilic infiltrate in the narrow caliber vessels of the superficial dermis. Renal biopsy most commonly varies from mild focal or segmental to diffuse necrotizing and sclerosing glomerulonephritis that shows minimal to no immune complex deposits on light and immunofluorescent microscopy ("pauci-immune").[19]

The importance of renal biopsy lies in the fact that the severity of renal involvement on histopathological evaluation correlates clinically with disease activity.[20] It thus plays an important role in guiding patient management and tapering immunosuppressive therapy. Although this is the mainstay, it has been shown that many patients may have diffuse interstitial nephritis without involving the glomeruli, which may pose a difficulty in diagnosis. Moreover, a few may have immune complex deposits in the glomeruli and experience more severe systemic signs and symptoms.

History and Physical

Patients with microscopic polyangiitis may present with constitutional symptoms, including insidious onset fever, arthralgia, myalgia, and weight loss. Other manifestations include urinary abnormalities, cough with or without hemoptysis, skin findings consistent with palpable purpura, mononeuritis multiplex, seizures, other non-specific neurological complaints, abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, chest pain, ocular pain, sinusitis, and testicular pain. Some patients may present with acute onset of fulminant disease with frank hemoptysis, hematuria, or even renal failure.

Renal Manifestations

The major renal feature of MPA is rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN).[21] Previous studies reported that 80 to 100% of MPA patients experience renal manifestations ranging from asymptomatic urinary sediment to end-stage renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy. Attributable to glomerulonephritis, the most common clinical features of renal involvement are microscopic hematuria, proteinuria, and granular or red blood cell (RBC) casts in urine.[22]

Pulmonary Manifestations

Pulmonary involvement can be observed in 25 to 55% of cases. In a large study, 80% of MPA patients were observed to have symptoms of pulmonary involvement, and 92% were found to have radiographic changes.[23] The most common pulmonary feature is diffuse alveolar hemorrhage; however, some patients may develop chronic interstitial fibrosis causing respiratory failure.[24] Common manifestations of an alveolar hemorrhage include hemoptysis, cough, dyspnea, and pleuritic chest pain.[25]

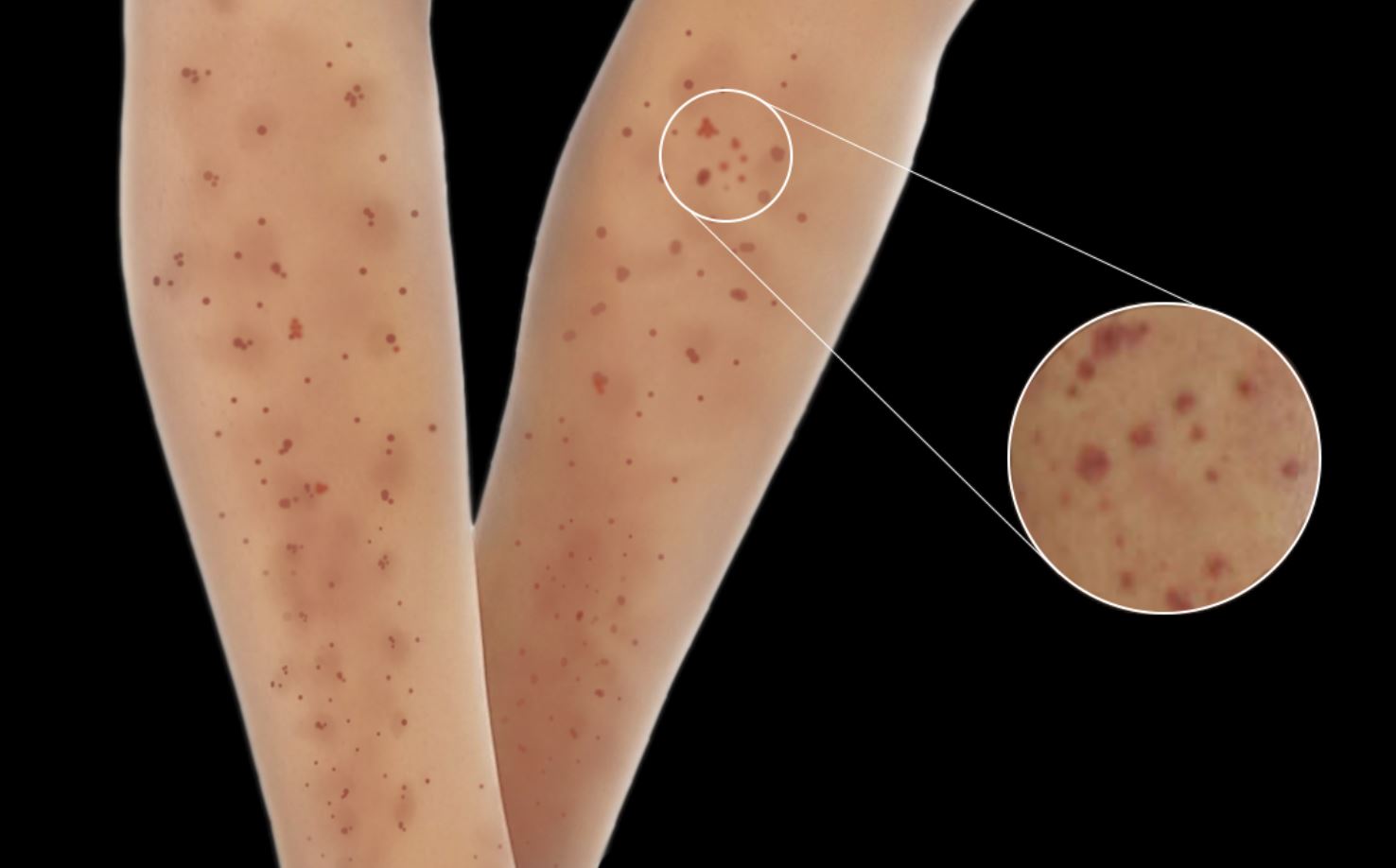

Skin Manifestations

Skin lesions are seen in 30 to 60% of patients with MPA and are the initial presenting feature in 15 to 30% of patients.[26][27] Skin manifestations include palpable purpura, livedo reticularis, urticaria, nodules, and skin ulcers with necrosis.[28] Skin manifestations have been associated with joint pains in patients with MPA.

Gastrointestinal Manifestations

Abdominal pain is the most frequently observed gastrointestinal symptom in MPA. While gastrointestinal bleeding may occur in some cases, massive hemorrhage is rare.[29]

Neurological Manifestations

Neurologic involvement is common in MPA, and peripheral neuropathy is more frequent than central nervous system involvement. Predominant peripheral nervous system features include distal symmetrical polyneuropathy and mononeuritis multiplex. Sural nerve biopsy reveals necrotizing vasculitis in up to 80% of cases, and nerve conduction studies show acute axonopathy.[30] Rarely can patients present with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES).[31] Central nervous system manifestations are varied and can include cerebral hemorrhage, non-hemorrhagic cerebral infarctions, and pachymeningitis.[32]

Physical examination may show ulceronodular skin lesions of the extremities, fever, tachypnea, and tachycardia. Skin examination findings include leukocytoclastic angiitis and its palpable purpura, livedo reticularis, skin ulcerations, necrosis and gangrene, necrotizing nodules, digital ischemia, and urticaria. A pulmonary examination may be significant for rales or bronchial breath sounds in pulmonary capillaritis cases, and a neurological exam may show motor or sensory deficits localized to a particular dermatome. Cardiovascular findings include hypertension, signs of heart failure, myocardial infarction, and pericarditis. Gastrointestinal bleeding, bowel ischemia, and perforation are gastrointestinal examination findings. The ocular examination can reveal retinal hemorrhage, scleritis, and uveitis. Other physical findings will vary depending on the involved capillary bed.

Evaluation

Evaluation of a patient suspected of microscopic polyangiitis involves a thorough clinical, radiological, histopathological, and lab evaluation:

- A detailed clinical evaluation to elicit the site and extent of involvement of the different organ systems is the first step in the evaluation.

- Lab Evaluation: It involves routine complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes, and measurement of serum titers of MPO and PR3 antibodies, which may be seen in most cases. However, low serum levels cannot be used to rule out AAV reliably.

- The complete blood cell count (CBC) shows leukocytosis and anemia.

- The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is elevated.

- Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine levels are elevated.

- Abnormal urine sediments, proteinuria, hematuria, leukocyturia, and erythrocyte casts are found on urine examination.

- The antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) test is positive in 80% of cases. Among these, perinuclear ANCA, related to myeloperoxidase, is present in 60%, while cytoplasmic ANCA, related to proteinase-3 ANCA, is present in 40%.

- Blood cultures may be performed to rule out bacterial endocarditis.

- On complement testing, C3 and C4 levels are normal.

- Radiological Evaluation: It involves a chest X-ray and a CT scan of the chest to look for pulmonary lesions in the case of patients presenting with hemoptysis and pulmonary fibrosis.[33] It also helps differentiate between GPA and MPA, with the former having cavitary and nodular lesions on radiological evaluation. Abdominal computed tomography may be done for pancreatitis or mesenteric angiography to differentiate MPA from polyarteritis nodosa.[34]

- Other Tests:

- Electrocardiography (ECG) - For myocardial infarction, pericarditis, or heart failure

- Gastrointestinal endoscopy - In cases of gastrointestinal bleeding

- Electromyography (EMG) - In cases of clinical evidence of neuropathy[35]

- Histopathological Evaluation: This should be done when possible (skin, renal. and lung biopsy) to look for evidence of vasculitis and immune deposits. The extent of inflammation seen on renal biopsy may be used to measure disease activity and help guide treatment.

Treatment / Management

Treatment of microscopic polyangiitis involves extensive use of corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive agents in different combinations. The aim of treatment has been defined in 2 parts: induction of remission and, subsequently, maintenance of remission. MPA can manifest as a mild disease with mild systemic vasculitis and renal insufficiency. However, it can also present as an acute severe disease with rapid deterioration of renal function and pulmonary capillaritis that leads to respiratory failure. The choice of medication depends on the extent of the disease, the rate of progression, and the degree of inflammation.

It is essential to know that remission does not imply the complete absence of symptoms; instead, the term is used to convey the absence of symptoms attributable to active vasculitis.[36] The treatment for relapse of MPA is the same as that of remission induction. Intravenous immunoglobulin has been used in the treatment of refractory disease.[37] The commonly used immunosuppressive agents in MPA management include cyclophosphamide, rituximab, methotrexate, glucocorticoids, azathioprine, and a few other biological agents.(B2)

Induction of Remission

Generally, remission is achieved using a combination of glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide. Rituximab is a comparable substitute to cyclophosphamide in terms of safety and efficacy for the induction of remission in MPA. However, in the severe form of diseases, induction using cyclophosphamide with glucocorticoids may be the first-line option. Cyclophosphamide is started at 1.5 to 2 mg/kg/day. The CBC should be monitored for leukocytopenia and neutropenia. Prednisone is started at 1 mg/kg/day and is continued for one month. Induction of remission may take between 2 and 6 months.[38](A1)

Treatment of the severe disease may include corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, and plasmapheresis.[39] Plasmapheresis is effective in cases of pulmonary hemorrhage and severe renal disease.[40] In patients where serum creatinine is more than 500 mmol/l, plasma exchange as an additional measure increases the rate of renal improvement.[41] A 24% risk reduction of end-stage renal failure was seen in randomization to plasma exchange at 12 months.[42][43](B3)

Maintenance of Remission

After complete remission, the maintenance phase is started. In case of life-threatening alveolar capillaritis with pulmonary alveolar hemorrhage, plasmapheresis is done in addition to intravenous cyclophosphamide, and pulse doses of steroids may be used. The Rituximab versus Cyclophosphamide for Induction of Remission in AAV trial (RAVE trial) established that comparable results could be achieved using rituximab, especially in individuals experiencing side effects of cyclophosphamide therapy.[44] Typically remission is achieved in most individuals over a period of 2 to 6 months.(A1)

Maintenance therapy is started after induction of remission and typically involves the use of azathioprine compared to cyclophosphamide, as demonstrated by the Cyclophosphamide versus Azathioprine for Early Remission Phase of Vasculitis trial (CYCAZAREM trial).[45] Azathioprine is given in a dose of 2 mg/kg/day for 12 months. After one year, the dose of azathioprine is decreased to 1.5 mg/kg/d. If methotrexate is used in maintenance therapy, it can be started at 0.3 mg/kg once a week, with a maximum dose of 15 mg/week. This is increased by 2.5 mg/week (maximum 20 mg/week). This phase lasts for 12 to 24 months. Prednisone can be continued at 10 mg/day or every other day. Low-dose cyclosporine has also been used for maintenance therapy.(A1)

Pneumocystis jiroveci prophylaxis with low-dose trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole is necessary.

Differential Diagnosis

Many conditions may mimic AAV/MPG and must be excluded before a diagnosis can be established. These include:

Infectious Etiologies

- Infective endocarditis

- Disseminated Gonococcosis

- Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) and other tick-born vasculitides

- Disseminated fungal infections

Malignancies

- Atrial myxomas

- Lymphomas

- Carcinomatosis

Drug Toxicities

- Cocaine

- Amphetamines

- Ergot alkaloids

- Levamisole

Other Autoimmune Conditions

- Amyloidosis

- Goodpasture disease[46]

- Sarcoidosis

- Polyarteritis nodosa

- Leukocytoclastic vasculitis

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Crescentic glomerulonephritis

- Cryoglobulinemia

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

The immunosuppressive agents used in managing AAV have serious side effects, which may be more debilitating than the manifestations of the disease. These include:

Glucocorticoids

- Osteoporosis[47]

- Cataract

- Glaucoma

- Diabetes mellitus

- Electrolyte abnormalities

- Avascular necrosis of bone

Cyclophosphamide

- Bone marrow suppression

- Hemorrhagic cystitis[48]

- Bladder carcinoma

- myelodysplasia

Methotrexate

- Hepatotoxicity

- Pneumonitis

- Bone marrow suppression

Azathioprine

- Hepatotoxicity

- Bone marrow suppression

Rituximab

- Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

- Opportunistic infections

Prognosis

When treated appropriately, about 90% of all microscopic polyangiitis patients show improvement, and roughly 75% achieve complete remission. The condition has a 5-year survival rate of 75%. MPA has a poorer survival rate than Churgg-Strauss syndrome or granulomatosis with polyangiitis, likely resulting from renal impairment present at the onset of the disease.[49]

Long-term damage in a cohort of 296 patients with MPA or GPA was linked to the severity of primary disease, the number of relapses, older age, and the duration of glucocorticoid treatment. A follow-up of 7 years post-diagnosis was conducted. The mean duration of glucocorticoid therapy was 40.4 months.[50]

In another study of 151 AAV patients, cases with lung involvement at baseline showed increased damage and disease activity scores at 6, 12, and 24 months. Patients with pulmonary involvement had a higher risk of developing renal and cardiovascular involvement and were more prone to developing pulmonary fibrosis.[51]

Complications

If left untreated, microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) can result in permanent damage to the organs. Kidney failure is the most common complication. MPA complications will depend on the particular organ system involved. Research has shown that older age, diastolic hypertension, and positive PR3-ANCA status correlate with cardiovascular events.[52]

The medications that treat MPA can also carry adverse complications. For example, cyclophosphamide has a relatively strong correlation with bladder cancer in those treated with the drug. In addition, steroids are known to cause bone loss, hyperglycemia, muscle weakness, and skin problems.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients must understand the seriousness of their condition and that they may not return to full pre-disease function and strength. Medication and therapy adherence is crucial, as are frequent follow-ups. Patients should be monitored closely as the immunosuppressive treatment continues for more than a year, and disease activity is measured with ANCA levels. Patients must be told the adverse effects of the drugs they use and when to report them.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Microscopic polyangiitis is a complex condition to manage by the provider because of the heterogeneity in its clinical presentation and the patient-specific treatment that it demands. Good communication and an interprofessional medical team comprised of clinicians, nurses, radiologists, pathologists, and pharmacists may help ease this hurdle. The nurses play an essential role in monitoring and charting vitals, especially urine output, which is crucial in helping the provider decide on the treatment. Radiologists play a vital role in assisting image-guided tissue biopsy, which the pathologist then studies to confirm the presence of disease. Proper dosing and dispensing of immunosuppressive agents by pharmacists can help in the induction and maintenance of remission. In contrast, failure to do so can lead to severe systemic side effects of these drugs. Pharmacists must also perform medication reconciliation to ensure there are no drug-drug interactions.

To ease the process of deciding the appropriate treatment, researchers at Johns Hopkins University have teamed up to provide the revised Birmingham score, which can be used to classify the patient's disease state clinically.[53] All interprofessional team members must maintain accurate, updated patient records, so all professionals involved in care have access to the same patient data. Open communication channels between all team members are crucial to successful interprofessional care. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, Basu N, Cid MC, Ferrario F, Flores-Suarez LF, Gross WL, Guillevin L, Hagen EC, Hoffman GS, Jayne DR, Kallenberg CG, Lamprecht P, Langford CA, Luqmani RA, Mahr AD, Matteson EL, Merkel PA, Ozen S, Pusey CD, Rasmussen N, Rees AJ, Scott DG, Specks U, Stone JH, Takahashi K, Watts RA. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2013 Jan:65(1):1-11. doi: 10.1002/art.37715. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23045170]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChung SA, Seo P. Microscopic polyangiitis. Rheumatic diseases clinics of North America. 2010 Aug:36(3):545-58. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2010.04.003. Epub 2010 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 20688249]

Greco A, Rizzo MI, De Virgilio A, Gallo A, Fusconi M, Pagliuca G, Martellucci S, Turchetta R, Longo L, De Vincentiis M. Goodpasture's syndrome: a clinical update. Autoimmunity reviews. 2015 Mar:14(3):246-53. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.11.006. Epub 2014 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 25462583]

Kallenberg CG,Heeringa P,Stegeman CA, Mechanisms of Disease: pathogenesis and treatment of ANCA-associated vasculitides. Nature clinical practice. Rheumatology. 2006 Dec [PubMed PMID: 17133251]

de Lind van Wijngaarden RA, van Rijn L, Hagen EC, Watts RA, Gregorini G, Tervaert JW, Mahr AD, Niles JL, de Heer E, Bruijn JA, Bajema IM. Hypotheses on the etiology of antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody associated vasculitis: the cause is hidden, but the result is known. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2008 Jan:3(1):237-52 [PubMed PMID: 18077783]

Pendergraft WF 3rd, Niles JL. Trojan horses: drug culprits associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody (ANCA) vasculitis. Current opinion in rheumatology. 2014 Jan:26(1):42-9. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000014. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24276086]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWakamatsu K, Mitsuhashi Y, Yamamoto T, Tsuboi R. Propylthiouracil-induced antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody positive vasculitis clinically mimicking pyoderma gangrenosum. The Journal of dermatology. 2012 Aug:39(8):736-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01399.x. Epub 2011 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 22132781]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLyons PA,Rayner TF,Trivedi S,Holle JU,Watts RA,Jayne DR,Baslund B,Brenchley P,Bruchfeld A,Chaudhry AN,Cohen Tervaert JW,Deloukas P,Feighery C,Gross WL,Guillevin L,Gunnarsson I,Harper L,Hrušková Z,Little MA,Martorana D,Neumann T,Ohlsson S,Padmanabhan S,Pusey CD,Salama AD,Sanders JS,Savage CO,Segelmark M,Stegeman CA,Tesař V,Vaglio A,Wieczorek S,Wilde B,Zwerina J,Rees AJ,Clayton DG,Smith KG, Genetically distinct subsets within ANCA-associated vasculitis. The New England journal of medicine. 2012 Jul 19 [PubMed PMID: 22808956]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceVega Miranda J, Pinto Peñaranda LF, Márquez Hernández JD, Velásquez Franco CJ. Microscopic polyangiitis secondary to silica exposure. Reumatologia clinica. 2014 May-Jun:10(3):180-2. doi: 10.1016/j.reuma.2013.04.009. Epub 2013 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 23886979]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBerti A, Cornec D, Crowson CS, Specks U, Matteson EL. The Epidemiology of Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Autoantibody-Associated Vasculitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota: A Twenty-Year US Population-Based Study. Arthritis & rheumatology (Hoboken, N.J.). 2017 Dec:69(12):2338-2350. doi: 10.1002/art.40313. Epub 2017 Nov 9 [PubMed PMID: 28881446]

Lane SE, Watts R, Scott DG. Epidemiology of systemic vasculitis. Current rheumatology reports. 2005 Aug:7(4):270-5 [PubMed PMID: 16045829]

Gonzalez-Gay MA, Garcia-Porrua C, Guerrero J, Rodriguez-Ledo P, Llorca J. The epidemiology of the primary systemic vasculitides in northwest Spain: implications of the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference definitions. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2003 Jun 15:49(3):388-93 [PubMed PMID: 12794795]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMohammad AJ, Jacobsson LT, Mahr AD, Sturfelt G, Segelmark M. Prevalence of Wegener's granulomatosis, microscopic polyangiitis, polyarteritis nodosa and Churg-Strauss syndrome within a defined population in southern Sweden. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 2007 Aug:46(8):1329-37 [PubMed PMID: 17553910]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFlossmann O, Berden A, de Groot K, Hagen C, Harper L, Heijl C, Höglund P, Jayne D, Luqmani R, Mahr A, Mukhtyar C, Pusey C, Rasmussen N, Stegeman C, Walsh M, Westman K, European Vasculitis Study Group. Long-term patient survival in ANCA-associated vasculitis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2011 Mar:70(3):488-94. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.137778. Epub 2010 Nov 24 [PubMed PMID: 21109517]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHagen EC, Daha MR, Hermans J, Andrassy K, Csernok E, Gaskin G, Lesavre P, Lüdemann J, Rasmussen N, Sinico RA, Wiik A, van der Woude FJ. Diagnostic value of standardized assays for anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in idiopathic systemic vasculitis. EC/BCR Project for ANCA Assay Standardization. Kidney international. 1998 Mar:53(3):743-53 [PubMed PMID: 9507222]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKallenberg CG,Stegeman CA,Abdulahad WH,Heeringa P, Pathogenesis of ANCA-associated vasculitis: new possibilities for intervention. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2013 Dec [PubMed PMID: 23810690]

Massicotte-Azarniouch D, Herrera CA, Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Free ME. Mechanisms of vascular damage in ANCA vasculitis. Seminars in immunopathology. 2022 May:44(3):325-345. doi: 10.1007/s00281-022-00920-0. Epub 2022 Mar 7 [PubMed PMID: 35254509]

Frankel SK, Schwarz MI. The pulmonary vasculitides. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2012 Aug 1:186(3):216-24. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0539CI. Epub 2012 Jun 7 [PubMed PMID: 22679011]

Sun L, Wang H, Jiang X, Mo Y, Yue Z, Huang L, Liu T. Clinical and pathological features of microscopic polyangiitis in 20 children. The Journal of rheumatology. 2014 Aug:41(8):1712-9. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.131300. Epub 2014 Jul 1 [PubMed PMID: 24986845]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHauer HA,Bajema IM,van Houwelingen HC,Ferrario F,Noël LH,Waldherr R,Jayne DR,Rasmussen N,Bruijn JA,Hagen EC, Renal histology in ANCA-associated vasculitis: differences between diagnostic and serologic subgroups. Kidney international. 2002 Jan [PubMed PMID: 11786087]

Lababidi MH, Odigwe C, Okolo C, Elhassan A, Iroegbu N. Microscopic polyangiitis causing diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center). 2015 Oct:28(4):469-71 [PubMed PMID: 26424944]

Wang H, Sun L, Tan W. Clinical features of children with pulmonary microscopic polyangiitis: report of 9 cases. PloS one. 2015:10(4):e0124352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124352. Epub 2015 Apr 29 [PubMed PMID: 25923706]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWilke L, Prince-Fiocco M, Fiocco GP. Microscopic polyangiitis: a large single-center series. Journal of clinical rheumatology : practical reports on rheumatic & musculoskeletal diseases. 2014 Jun:20(4):179-82. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000108. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24847742]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKarras A. Microscopic Polyangiitis: New Insights into Pathogenesis, Clinical Features and Therapy. Seminars in respiratory and critical care medicine. 2018 Aug:39(4):459-464. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1673387. Epub 2018 Nov 7 [PubMed PMID: 30404112]

Barowka SE, Perrine TR, Hughes K. "I'm coughing up blood". Journal of the Mississippi State Medical Association. 2016 Nov:57(11):354-356 [PubMed PMID: 30281235]

Kluger N, Pagnoux C, Guillevin L, Francès C, French Vasculitis Study Group. Comparison of cutaneous manifestations in systemic polyarteritis nodosa and microscopic polyangiitis. The British journal of dermatology. 2008 Sep:159(3):615-20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08725.x. Epub 2008 Jul 19 [PubMed PMID: 18647311]

Lhote F, Cohen P, Guillevin L. Polyarteritis nodosa, microscopic polyangiitis and Churg-Strauss syndrome. Lupus. 1998:7(4):238-58 [PubMed PMID: 9643314]

Gibson LE, Cutaneous manifestations of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis (AAV): a concise review with emphasis on clinical and histopathologic correlation. International journal of dermatology. 2022 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 35599359]

Eriksson P, Segelmark M, Hallböök O. Frequency, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcome of Gastrointestinal Disease in Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis and Microscopic Polyangiitis. The Journal of rheumatology. 2018 Apr:45(4):529-537. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.170249. Epub 2018 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 29419474]

Hattori N, Mori K, Misu K, Koike H, Ichimura M, Sobue G. Mortality and morbidity in peripheral neuropathy associated Churg-Strauss syndrome and microscopic polyangiitis. The Journal of rheumatology. 2002 Jul:29(7):1408-14 [PubMed PMID: 12136898]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceXu J, Ding Y, Qu Z, Yu F. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome in a Patient With Microscopic Polyangiitis: A Case Report and Literature Review. Frontiers in medicine. 2021:8():792744. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.792744. Epub 2021 Dec 24 [PubMed PMID: 35071272]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKu BD,Shin HY, Multiple bilateral non-hemorrhagic cerebral infarctions associated with microscopic polyangiitis. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery. 2009 Dec [PubMed PMID: 19733002]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEschun GM, Mink SN, Sharma S. Pulmonary interstitial fibrosis as a presenting manifestation in perinuclear antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody microscopic polyangiitis. Chest. 2003 Jan:123(1):297-301 [PubMed PMID: 12527637]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceIida T, Adachi T, Tabeya T, Nakagaki S, Yabana T, Goto A, Kondo Y, Kasai K. Rare type of pancreatitis as the first presentation of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-related vasculitis. World journal of gastroenterology. 2016 Feb 21:22(7):2383-90. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i7.2383. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26900301]

Sassi SB, Ghorbel IB, Mizouni H, Houman MH, Hentati F. Microscopic polyangiitis presenting with peripheral and central neurological manifestations. Neurological sciences : official journal of the Italian Neurological Society and of the Italian Society of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2011 Aug:32(4):727-9. doi: 10.1007/s10072-011-0653-x. Epub 2011 Jun 17 [PubMed PMID: 21681367]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNachman PH,Hogan SL,Jennette JC,Falk RJ, Treatment response and relapse in antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-associated microscopic polyangiitis and glomerulonephritis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 1996 Jan [PubMed PMID: 8808107]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCrickx E, Machelart I, Lazaro E, Kahn JE, Cohen-Aubart F, Martin T, Mania A, Hatron PY, Hayem G, Blanchard-Delaunay C, de Moreuil C, Le Guenno G, Vandergheynst F, Maurier F, Crestani B, Dhote R, Silva NM, Ollivier Y, Mehdaoui A, Godeau B, Mariette X, Cadranel J, Cohen P, Puéchal X, Le Jeunne C, Mouthon L, Guillevin L, Terrier B, French Vasculitis Study Group. Intravenous Immunoglobulin as an Immunomodulating Agent in Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody-Associated Vasculitides: A French Nationwide Study of Ninety-Two Patients. Arthritis & rheumatology (Hoboken, N.J.). 2016 Mar:68(3):702-12. doi: 10.1002/art.39472. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26473632]

de Groot K, Harper L, Jayne DR, Flores Suarez LF, Gregorini G, Gross WL, Luqmani R, Pusey CD, Rasmussen N, Sinico RA, Tesar V, Vanhille P, Westman K, Savage CO, EUVAS (European Vasculitis Study Group). Pulse versus daily oral cyclophosphamide for induction of remission in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis: a randomized trial. Annals of internal medicine. 2009 May 19:150(10):670-80 [PubMed PMID: 19451574]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFrankel SK, Cosgrove GP, Fischer A, Meehan RT, Brown KK. Update in the diagnosis and management of pulmonary vasculitis. Chest. 2006 Feb:129(2):452-465. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.2.452. Epub [PubMed PMID: 16478866]

Falk RJ, Jennette JC. ANCA disease: where is this field heading? Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2010 May:21(5):745-52. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009121238. Epub 2010 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 20395376]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSmith RM, Jones RB, Jayne DR. Progress in treatment of ANCA-associated vasculitis. Arthritis research & therapy. 2012 Apr 30:14(2):210. doi: 10.1186/ar3797. Epub 2012 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 22569190]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMillet A, Pederzoli-Ribeil M, Guillevin L, Witko-Sarsat V, Mouthon L. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitides: is it time to split up the group? Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2013 Aug:72(8):1273-9. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203255. Epub 2013 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 23606701]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceThurner L, Preuss KD, Fadle N, Regitz E, Klemm P, Zaks M, Kemele M, Hasenfus A, Csernok E, Gross WL, Pasquali JL, Martin T, Bohle RM, Pfreundschuh M. Progranulin antibodies in autoimmune diseases. Journal of autoimmunity. 2013 May:42():29-38. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2012.10.003. Epub 2012 Nov 11 [PubMed PMID: 23149338]

Specks U, Merkel PA, Seo P, Spiera R, Langford CA, Hoffman GS, Kallenberg CG, St Clair EW, Fessler BJ, Ding L, Viviano L, Tchao NK, Phippard DJ, Asare AL, Lim N, Ikle D, Jepson B, Brunetta P, Allen NB, Fervenza FC, Geetha D, Keogh K, Kissin EY, Monach PA, Peikert T, Stegeman C, Ytterberg SR, Mueller M, Sejismundo LP, Mieras K, Stone JH, RAVE-ITN Research Group. Efficacy of remission-induction regimens for ANCA-associated vasculitis. The New England journal of medicine. 2013 Aug 1:369(5):417-27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213277. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23902481]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJayne D, Rasmussen N, Andrassy K, Bacon P, Tervaert JW, Dadoniené J, Ekstrand A, Gaskin G, Gregorini G, de Groot K, Gross W, Hagen EC, Mirapeix E, Pettersson E, Siegert C, Sinico A, Tesar V, Westman K, Pusey C, European Vasculitis Study Group. A randomized trial of maintenance therapy for vasculitis associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies. The New England journal of medicine. 2003 Jul 3:349(1):36-44 [PubMed PMID: 12840090]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWard ND, Cosner DE, Lamb CA, Li W, Macknis JK, Rooney MT, Zhang PL. Top Differential Diagnosis Should Be Microscopic Polyangiitis in ANCA-Positive Patient with Diffuse Pulmonary Hemorrhage and Hemosiderosis. Case reports in pathology. 2014:2014():286030. doi: 10.1155/2014/286030. Epub 2014 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 25525543]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChotiyarnwong P, McCloskey EV. Pathogenesis of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis and options for treatment. Nature reviews. Endocrinology. 2020 Aug:16(8):437-447. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-0341-0. Epub 2020 Apr 14 [PubMed PMID: 32286516]

Haldar S, Dru C, Bhowmick NA. Mechanisms of hemorrhagic cystitis. American journal of clinical and experimental urology. 2014:2(3):199-208 [PubMed PMID: 25374922]

Kitching AR, Anders HJ, Basu N, Brouwer E, Gordon J, Jayne DR, Kullman J, Lyons PA, Merkel PA, Savage COS, Specks U, Kain R. ANCA-associated vasculitis. Nature reviews. Disease primers. 2020 Aug 27:6(1):71. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0204-y. Epub 2020 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 32855422]

Robson J, Doll H, Suppiah R, Flossmann O, Harper L, Höglund P, Jayne D, Mahr A, Westman K, Luqmani R. Glucocorticoid treatment and damage in the anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody-associated vasculitides: long-term data from the European Vasculitis Study Group trials. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 2015 Mar:54(3):471-81. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu366. Epub 2014 Sep 8 [PubMed PMID: 25205825]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHassan TM, Hassan AS, Igoe A, Logan M, Gunaratnam C, McElvaney NG, O'Neill SJ. Lung involvement at presentation predicts disease activity and permanent organ damage at 6, 12 and 24 months follow - up in ANCA - associated vasculitis. BMC immunology. 2014 May 27:15():20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-15-20. Epub 2014 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 24884372]

Robson J, Doll H, Suppiah R, Flossmann O, Harper L, Höglund P, Jayne D, Mahr A, Westman K, Luqmani R. Damage in the anca-associated vasculitides: long-term data from the European vasculitis study group (EUVAS) therapeutic trials. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2015 Jan:74(1):177-84. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203927. Epub 2013 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 24243925]

Stone JH, Hoffman GS, Merkel PA, Min YI, Uhlfelder ML, Hellmann DB, Specks U, Allen NB, Davis JC, Spiera RF, Calabrese LH, Wigley FM, Maiden N, Valente RM, Niles JL, Fye KH, McCune JW, St Clair EW, Luqmani RA, International Network for the Study of the Systemic Vasculitides (INSSYS). A disease-specific activity index for Wegener's granulomatosis: modification of the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score. International Network for the Study of the Systemic Vasculitides (INSSYS). Arthritis and rheumatism. 2001 Apr:44(4):912-20 [PubMed PMID: 11318006]