Introduction

Cholesteatoma is a confusing misnomer which means fatty bile tumor; however, cholesteatomas are benign collections of keratinized squamous epithelium within the middle ear. There are two major types of middle ear cholesteatomas, congenital and acquired. Congenital cholesteatomas are derived from remnants of epithelium that get trapped behind the tympanic membrane during development. Acquired cholesteatomas do not result from an embryologic phenomenon, but are the result of pathologic changes that cause the uncontrolled growth of squamous keratinized epithelium in the middle ear. While the lesions are benign, they can erode into the CNS and cause severe complications. When the cholesteatoma is infected, it is very difficult to cure. Since the lesion has no blood supply, systemic antibiotics cannot get inside the center of the mass. Topical antibiotics only clear superficial infection and thus the ear discharge continues or is recurrent.

This activity will focus on the most common type of cholesteatoma, acquired middle ear cholesteatoma.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The pathogenesis of acquired cholesteatoma is not fully understood; however, there are four major theories that help explain the etiology of this disease. The first is the squamous metaplasia theory, which suggests that inflammation causes the mucosal lining of the middle ear to become hyperproliferative. The second major theory postulates that squamous epithelium from the outer layer of the tympanic membrane migrates through a perforation through the drum and into the middle ear. Basal hyperplasia theory is the third theory, which assumes that basal cells of the tympanic membrane proliferate and move medially through the basement membrane into the middle ear. The fourth and final theory is the retraction pocket theory, which is accepted by many otolaryngologists. So much so, in fact, that cholesteatoma resulting from a retraction pocket is named primary acquired cholesteatoma[1][2]. A secondary acquired cholesteatoma is formed by infection, trauma, or surgical manipulation causing implantation of skin into the middle ear through a defect in the eardrum. Despite these distinct categories, there may be a component of all four theories involved in the disease. Regardless of the etiology, once middle ear cholesteatomas have formed, they continue to proliferate and migrate causing damage to surrounding structures in the middle ear.

The congenital variety usually obstructs the eustachian tube and produces middle ear fluid and conductive hearing loss. The majority of these lesions are unilateral.

The primary acquired cholesteatoma occurs as a result of tympanic membrane retraction. As the membrane retracts, the cholesteatoma can damage the ossicles and erode into the aditus ad antrum and the mastoid. Sometimes the facial nerve may be exposed.

Epidemiology

The true worldwide incidence of middle ear cholesteatoma is not known. Many retrospective studies that provide helpful demographical statistics have been done. In the United States, one study reported six cholesteatomas per 100,000 people[3]. The average age for children to be diagnosed with acquired cholesteatoma was 9.7 years. Acquired cholesteatomas are about 1.4 times more likely to occur in men compared to women. One English study showed an increased incidence of cholesteatoma in socioeconomically deprived areas, suggesting that the incidence of acquired cholesteatoma is higher among low-income patients, though more research in this area is needed.[4]

Pathophysiology

The accumulation of skin in the middle ear can cause many problems and damage nearby structures. One of the most common problems is hearing loss due to the erosion of the middle ear bones. The cholesteatoma causes an inflammatory reaction that releases lytic enzymes, growth factors, and cytokines which can recruit osteoclasts to initiate destruction of bone. Cholesteatoma, if left untreated, can also erode the bony confines of the middle ear and extend to adjacent areas such as the face, brain, and the neck. When cholesteatomas become infected, they can grow faster and cause more bony erosion. They can also cause a chronically draining ear, which is often foul smelling.

History and Physical

The classic presentation of cholesteatoma is painless otorrhea. Hearing loss is a common symptom of cholesteatoma. In the presence of ossicular damage, the hearing loss is often permanent and severe. Other symptoms include dizziness.

History and physical exam are both crucial in the timely diagnosis of acquired cholesteatoma. In addition to the fundamental history of present illness questions, providers should ask appropriate questions in basic patient-friendly terms and document the patient’s responses. Some common questions would include: when did you first notice you had an ear problem, was it one side or both sides, have you been diagnosed with ear infections, have you received antibiotics by mouth or ear drops, if so which kinds of antibiotics? Recurrent infections or chronic drainage should raise suspicions. A review of systems questions includes subjective hearing loss, tinnitus, otorrhea, otalgia, ear pressure, and vertigo. Have you seen other doctors for this problem and have you had any imaging studies, if so where were they performed. It is often helpful to review the imaging before seeing the patient; this can assist in identifying the appropriate questions to ask. Patients often present complaining of foul-smelling discharge, hearing loss, and pain that has lasted for months to years.

The physical exam should include a full head and neck exam including inspection of the head, eyes, nose, oral cavity, oropharynx, neck and most importantly ears. Physical examination of the ear requires patience and practice, and children often need to be intentionally positioned by sitting on their parent's laps. Cholesteatomas are largely a visible diagnosis, and to visualize the middle ear cholesteatoma, providers must develop otoscopic examination skills. A microscope may also be useful. Collections of white keratinaceous debris can often be seen in the posterosuperior tympanic membrane quadrant.

Evaluation

Computed tomography with thin cuts of the temporal bone without contrast is the most commonly utilized diagnostic imaging modality among otolaryngologists. Imaging assists with surgical planning and provides a significant amount of useful information to the otolaryngologist. MRI can also be used to help with the diagnosis of acquired middle ear cholesteatomas. They often appear isointense on T1, hyperintense on T2 and do not enhance with gadolinium contrast. MRI may be more useful as a method of cholesteatoma surveillance after surgery.

Subtle defects seen on imaging include:

- Labyrinthine fistula

- Scutal erosion

- Ossicular involvement, erosion

- Defects in the tegmen

Audiometry should always be done prior to surgery to establish a baseline. The speech reception threshold, air, and bone conduction and speech discrimination scores should be noted.

Treatment / Management

The definitive treatment for cholesteatoma is surgical removal of the disease to provide a safe and dry ear. Patients often present with debilitating pain and hearing loss, and it is very important to explain that the goal of surgery is cholesteatoma removal and this may not restore the patient’s hearing to normal.[5] In fact, the patient’s hearing could decline after surgery, and it is important to discuss this possibility with the patient. Audiograms should be obtained before and after surgery. The type of surgery performed depends largely on the type and location of the cholesteatoma, but tympanomastoidectomy is commonly performed to ensure the removal of all cholesteatoma. There are two major types of mastoidectomies performed for this surgery: canal wall up (CWU) and canal wall down (CWD). Each has advantages and disadvantages, but the canal wall down procedures result in lower rates of recurrence but require lifelong mastoid cleaning for the patient.(B2)

Anywhere from 5-50% of surgeries will be unsuccessful and result in recurrence.

Differential Diagnosis

- Middle ear osteoma

- Suppurative otitis media

Prognosis

In most cases, the cholesteatoma can be removed but it often requires multiple surgeries. Today, complications from cholesteatoma are rare, Reoperation is only done in about 5% of patients when the canal wall down tympanomastoidectomy technique is used. The wall up technique is associated with a much higher rate of recurrence rates. Unfortunately, hearing loss is often permanent. Death from cholesteatoma is very rare today.

Complications

- Sigmoid sinus thrombosis

- Conductive hearing loss

- Meningitis

- Epidural abscess

Pearls and Other Issues

Physicians should always be concerned about prevention of cholesteatomas. Persistent eustachian tube dysfunction can cause retraction pockets. Tympanostomy tube placement early may eliminate negative middle ear pressure, reduce the risk of retraction pocket formation, and halt the initiation of cholesteatoma formation. Another important consideration is the disposition of cholesteatoma patients. Many of these patients have experienced symptoms over several months before being seen by a healthcare provider, and they may be delayed several more months before seeing an otolaryngologist. Ensuring close follow up is crucial as patients that have delayed interventions often have worse outcomes.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Interpersonal communication among providers will provide increased accuracy in diagnosis and prompt surgical treatment in middle ear cholesteatoma patients.

Media

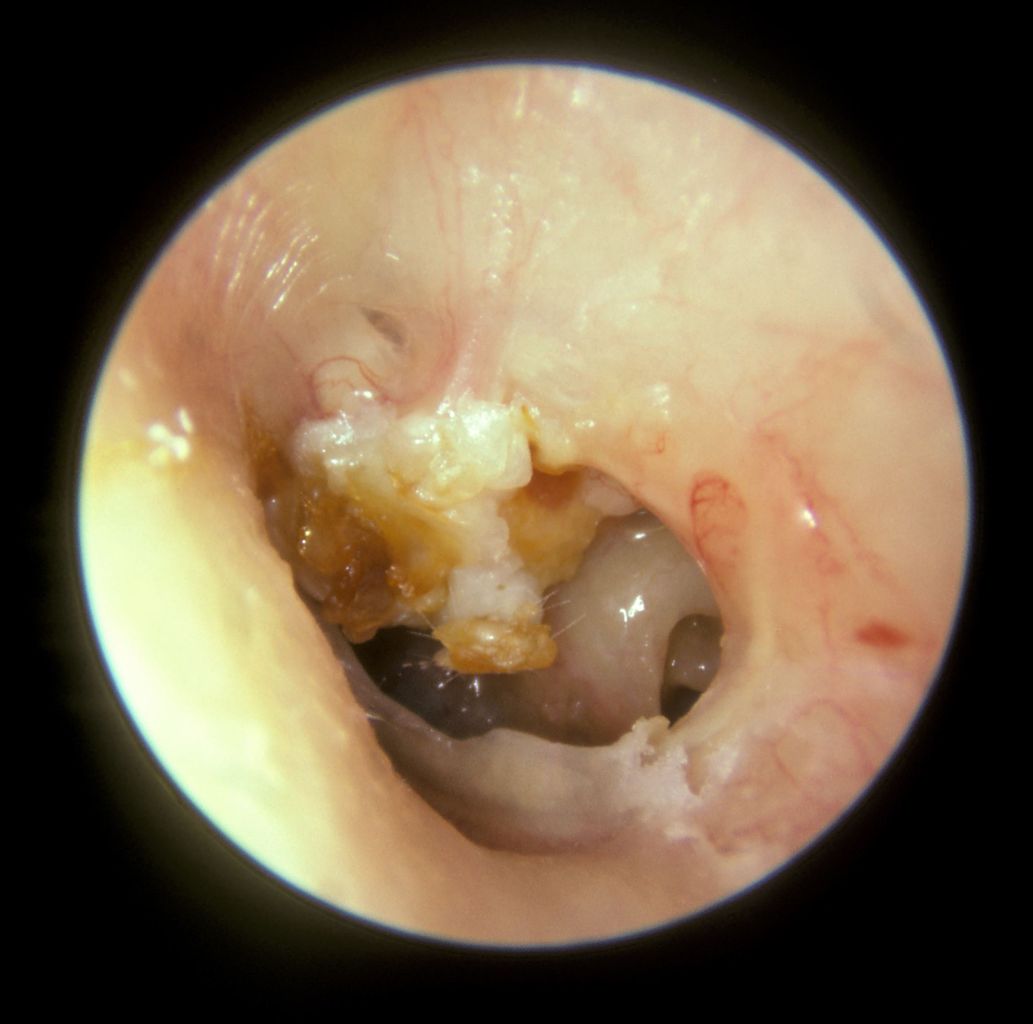

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The large mass of white keratin debris in the left upper quadrant of this left tympanic membrane is a cholesteatoma. The majority of the tympanic membrane is missing [perforation]. In the lower right quadrant the round window niche on the medial wall middleware can be seen. Contributed by Wikimedia Commons, Michael Hawke MD (CC by 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

References

Louw L. Acquired cholesteatoma: summary of the cascade of molecular events. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2013 Jun:127(6):542-9. doi: 10.1017/S0022215113000601. Epub 2013 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 23656971]

Jackler RK, Santa Maria PL, Varsak YK, Nguyen A, Blevins NH. A new theory on the pathogenesis of acquired cholesteatoma: Mucosal traction. The Laryngoscope. 2015 Aug:125 Suppl 4():S1-S14. doi: 10.1002/lary.25261. Epub 2015 May 25 [PubMed PMID: 26013635]

Aquino JE, Cruz Filho NA, de Aquino JN. Epidemiology of middle ear and mastoid cholesteatomas: study of 1146 cases. Brazilian journal of otorhinolaryngology. 2011 Jun:77(3):341-7 [PubMed PMID: 21739009]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKhalid-Raja M, Tikka T, Coulson C. Cholesteatoma: a disease of the poor (socially deprived)? European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2015 Oct:272(10):2799-805. doi: 10.1007/s00405-014-3285-y. Epub 2014 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 25231708]

Prasad SC, La Melia C, Medina M, Vincenti V, Bacciu A, Bacciu S, Pasanisi E. Long-term surgical and functional outcomes of the intact canal wall technique for middle ear cholesteatoma in the paediatric population. Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica : organo ufficiale della Societa italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale. 2014 Oct:34(5):354-61 [PubMed PMID: 25709151]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence