Introduction

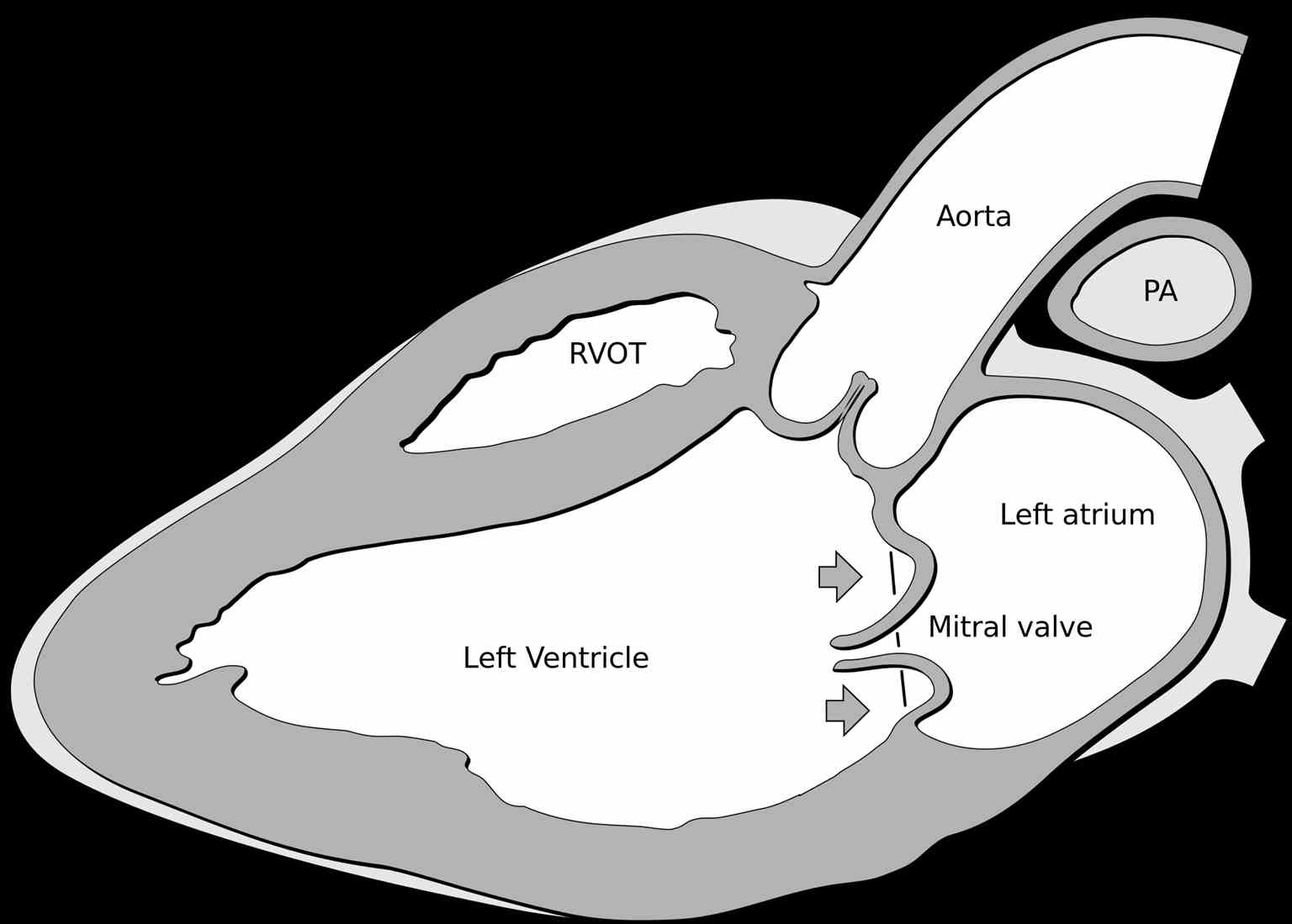

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP), also known as floppy mitral valve syndrome, systolic click-murmur syndrome, and billowing mitral leaflets, is a valvular heart disease disorder (see Image. Mitral Valve Prolapse). It is a benign condition. In rare cases, it may present with sudden cardiac death, endocarditis, or a stroke.[1][2][3]

The condition affects nearly 3% of the United States population. The disorder produces symptoms as a result of a redundant and abnormally thickened mitral valve leaflet prolapsing into the left atrium during systole.

MVP is usually identified during a clinical exam on cardiac auscultation. Echocardiography confirms the diagnosis. This disorder is the most common cause of the non-ischemic mitral valve is mitral regurgitation in the US. [4]

Symptomatic patients may need mitral valve repair.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

MVP usually occurs as an isolated condition in connective tissue disorders such as Marfan syndrome, Loeys-Dietz syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta, pseudoxanthoma elasticum, and aneurysms-osteoarthritis syndrome.[5]

Epidemiology

MVP is a common valvular disorder that affects up to 3% of the general population. This disorder affects approximately seven to eight million individuals in the United States and more than 16 million people globally. MVP can be classified as primary or secondary.

Primary mitral valve prolapse is characterized by myxomatous degeneration in the absence of any connective tissue pathology.

Secondary MVP can be multifactorial and can be seen with Ehler-Danlos Syndrome, Marfan syndrome, polycystic kidney disease, graves' disease, and pectus excavatum. MVP can be associated with significant mitral valve regurgitation (4%), bacterial endocarditis, congestive heart failure, and even sudden death.[6]

Genetic causes may be familial or sporadic and may include autosomal dominant inherited variants with affected chromosomes, including MMVP1 - chromosome 16p11.2-p12, MMVP2 - chromosome 11p15, and MMVP3 - chromosome 13q31.3-q32. Less commonly, it may be affected, and x linked mutation on chromosome Xq28 with missense mutation including P637Q, G288R, and V711D or can include in-frame 1944 base pair deletion.[7][4]

Pathophysiology

MVP is the primary myxomatous degeneration of one or both leaflets of the mitral valve. Myxomatous degeneration may involve valve leaflet abnormalities, chordae tendineae weakening and elongation, mitral annular dilatation or thickened leaflet tissue, elongated chordae, mitral annular enlargement leading to segmental mitral leaflet prolapse. Other pathophysiological changes include fibroelastic deficiency characterized by thin, translucent, and smooth leaflets or deficiency in elastin, proteoglycan, and collagen with connective tissue deficiency.[7][4]

Endothelium disruption leads to complications such as infectious endocarditis and thromboembolism. Most MVP individuals have minimal mitral valve structure derangement, which is not clinically significant. [8]

There is usually a gross redundancy of the mitral valve leaflets, which fails coaptation of the leaflets during systole, leading to mitral insufficiency. Over time the patient develops mitral annual dilatation, resulting in further worsening of the mitral insufficiency. Fortunately, most patients have minor derangements in the leaflets and are asymptomatic.

Histopathology

Histologically, MVP is characterized as a myxomatous degeneration or connective tissue disorder. The spongiosa of the mitral valve leaflets proliferates with mucopolysaccharide deposits with excessive water content. Thus resulting in leaflet thickening and redundancy.

Type III collagen content increases, and elastin fibers are fragmented.

History and Physical

MVP can be asymptomatic and can also present with symptoms of atypical chest pain, palpitations, dyspnea on exertion, and exercise intolerance. Other symptoms, such as anxiety, low blood pressure, and syncope, suggest autonomic nervous system dysfunction. Occasionally, supraventricular arrhythmias are seen, suggesting an increased parasympathetic tone.

In MVP, the mid-systolic click is followed by a late systolic murmur. This finding is commonly heard at the apex. The murmur of MVP varies with position. The murmur is accentuated when the patient is standing and in the Valsalva maneuver (systolic click comes earlier, and the murmur is longer) and diminishes when the patient is squatting (systolic click comes later, and the murmur is shorter).

The murmur of MVP is similar to the murmur of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A mid-systolic click is a diagnostic of MVP. The handgrip maneuver increases the murmur of MVP and decreases the murmur of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The handgrip maneuver also decreases the duration of the murmur and delays the timing of the mid-systolic click in MVP.

Over the years, it has been noted that patients with MVP do develop a range of autonomic symptoms that include:

- Panic attacks

- Anxiety

- Exercise intolerance

- Palpitations

- Fatigue

- Atypical chest discomfort

- Orthostasis

- Mood changes

- Syncope

Evaluation

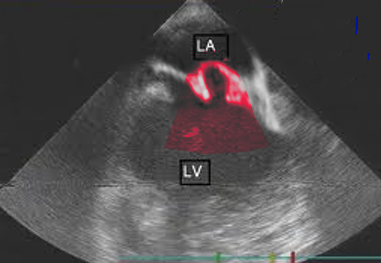

The most useful method of making a diagnosis of MVP is by echocardiogram (see Image. Mitral Valve Prolapse Echocardiography). M-Mode echocardiography is not used to diagnose MVP. This is because the normal movement of the base of the heart can mimic or mask MVP. The two- or three-dimensional echocardiogram allows the measurement of leaflet thickness and displacement relative to the annulus.[9][10][11]

Mitral Valve Prolapse is defined as mitral valve displacement more than 2 mm above the mitral annulus in a long-axis view (parasternal or apical three chambers). MVP is further subdivided into non-classic and classic based on the thickness of the mitral valve leaflets.

In non-classic MVP, mitral valve leaflet thickness is 0 mm to 5 mm. In classic MVP, mitral valve leaflet thickness is more than 5 mm.

Classic MVP is further subdivided into symmetric and asymmetric based on the point at which leaflets tips join the mitral annulus. In symmetric form, leaflet tips meet at a common point on the annulus. In asymmetric form, one leaflet is displaced toward the atrium with respect to the other.

Classic asymmetric MVP is further subdivided into flail and non-flail subtypes. In the flail subtype, prolapse occurs when a leaflet tip turns outward, becoming concave toward the left atrium causing mitral valve deterioration. The flail leaflet varies from tip eversion to chordal rupture. Dissociation of leaflet and chordae tendineae results in unrestricted motion of the leaflet, giving the name "flail leaflet." The flail leaflet has a higher prevalence of mitral regurgitation than the non-flail form.

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) clinical modality has not been evaluated in MVP. CMR enables the quantification of mitral regurgitation prior to mitral valve surgery.

Sometimes, MVP is discovered incidentally on left ventriculography during cardiac catheterization. This is characterized by the displacement of mitral valve leaflets into the left atrium with late systolic mitral valve regurgitation. In such individuals, MVP should be evaluated by echocardiography. If there is discordant between clinical and echocardiographic findings on the severity of mitral valve regurgitation, then cardiac catheterization and left ventriculography would be useful.

Treatment / Management

MVP patients with no symptoms often require no treatment.[12][13][14](B2)

MVP patients with symptoms of dysautonomia (chest pain, palpitations) should be treated with beta-blockers such as propranolol.

MVP with severe mitral regurgitation may benefit from mitral valve repair or mitral valve replacement. ACC/AHA guidelines recommend mitral valve repair before symptoms of congestive heart failure develop.

Individuals with MVP are at high risk for bacterial endocarditis. Until 2007, the American Heart Association (AHA) recommended prescribing antibiotics before invasive procedures, including dental surgery. Newer AHA guidelines recommend prophylaxis for dental procedures only should be advised for patients who have other cardiac conditions, which put them at the highest risk of adverse outcomes from infective endocarditis.

The association between MVP and a cerebral vascular event is low. The 2014 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) and 2012 European Society of Cardiology do not comment on antiplatelet/antithrombotic therapy in MVP. The 2006 ACC/AHA guidelines recommend aspirin for unexplained transient ischemic attacks in sinus rhythm with no atrial thrombi. Aspirin may be considered in sinus rhythm with echocardiographic evidence of high-risk MVP. Anticoagulation is recommended for systemic embolism or recurrent transient ischemic attacks (TIA) despite aspirin therapy. Anticoagulation is not recommended without systemic embolism, unexplained TIA, ischemic stroke, or atrial fibrillation.

Asymptomatic patients with mitral valve prolapse are managed conservatively with observation and monitoring. Patients with no concomitant mitral regurgitation can be followed every 3 to 5 years, and patients with mitral regurgitation can be followed annually. Patient reassurance is essential, along with recommendations for a healthy lifestyle and regular exercise. If the patient is symptomatic with palpitations, anxiety, or chest pain, other etiologies should be ruled out.

Symptomatic patients with severe mitral regurgitation, systolic heart failure, and symptom progression require surgical intervention. Asymptomatic patients with mitral valve prolapse with mitral regurgitation with systolic heart failure are also considered for surgical intervention.

Mitral valve repair is the recommended procedure over mitral valve replacement. Symptomatic patients with significant comorbidities who are surgical prohibitive risk can be considered for transcatheter mitral valve repair.

AHA has recommendations for athletes with mitral valve prolapse. Athletes who participate in high-intensity competitive sports can participate based on their clinical history. They can participate if they do not have a prior history of syncope, sustained or repetitive and non-sustained supraventricular tachycardia, severe mitral regurgitation, prior embolic event, left ventricular systolic dysfunction with ejection fraction < 50, family history of mitral valve prolapse related sudden cardiac death.

Athletes can participate in low-intensity competitive sports with the above-mentioned conditions.

Differential Diagnosis

MVP should be differentiated from other causes of mitral valve regurgitation.

Prognosis

The overall prognosis for MVP is benign. Most asymptomatic individuals are not aware that they have MVP and do not require treatment. Complications associated with MVP include infective endocarditis, mitral valve regurgitation, arrhythmia (atrial fibrillation), transient ischemic event, or systemic embolism. The major predictor of mortality in MVP is the degree of mitral valve regurgitation and ejection fraction.

Complications

- Progression to severe mitral regurgitation

- Infective endocarditis

- Atrial fibrillation

- Stroke

- Sudden death

Consultations

Cardiologist

Cardiothoracic surgeon

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients who have been diagnosed with MVP should be advised to seek medical advice if the symptoms become worse. They have more benefits in surgical treatment before they develop congestive heart failure.

Pearls and Other Issues

The prevalence of MVP in patients with Marfan's syndrome is 91%.[15]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of MVP is with an interprofessional team that includes a team of a cardiologist, cardiac nurse, primary care provider, and cardiac surgeon. Patients need to be educated that they have a benign disorder and the risk of complications is low. However, patients do need to be told about the symptoms of mitral regurgitation and endocarditis and when to present to the hospital.

Clinicians should educate patients that they should adopt a healthy lifestyle, not smoke, exercise regularly, and abstain from alcohol and caffeinated beverages. For those who develop palpitations, a trial of beta-blockers may prove to be useful.[16][17][18] [Level 5] These patients also need to be educated that, in most cases, antibiotic prophylaxis is not required before a dental procedure. The cardiac nurse should obtain an ECG if the patient complains of palpitations, as one of the reasons may be atrial arrhythmias.

Follow-up is necessary as some patients may develop worsening mitral insufficiency and intolerable symptoms. These patients are best referred to a cardiac thoracic surgeon.

Outcomes

The majority of patients with MVP have a normal life expectancy. About 3-10% of patients will have a progression of the condition to severe mitral regurgitation. In general, patients over the age of 50 at diagnosis and normal left ventricular function have an excellent outcome, even if they do develop MR. Death is rare from MVP today. Even for those who undergo repair or replacement of the valve, the outcomes are good to excellent. [19][20] [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Gati S, Malhotra A, Sharma S. Exercise recommendations in patients with valvular heart disease. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2019 Jan:105(2):106-110. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-313372. Epub 2018 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 30262455]

Nalliah CJ, Mahajan R, Elliott AD, Haqqani H, Lau DH, Vohra JK, Morton JB, Semsarian C, Marwick T, Kalman JM, Sanders P. Mitral valve prolapse and sudden cardiac death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2019 Jan:105(2):144-151. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312932. Epub 2018 Sep 21 [PubMed PMID: 30242141]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAyme-Dietrich E,Lawson R,Da-Silva S,Mazzucotelli JP,Monassier L, Serotonin contribution to cardiac valve degeneration: new insights for novel therapies? Pharmacological research. 2019 Feb [PubMed PMID: 30208338]

Hayek E,Gring CN,Griffin BP, Mitral valve prolapse. Lancet (London, England). 2005 Feb 5-11; [PubMed PMID: 15705461]

Spartalis M, Tzatzaki E, Spartalis E, Athanasiou A, Moris D, Damaskos C, Garmpis N, Voudris V. Mitral valve prolapse: an underestimated cause of sudden cardiac death-a current review of the literature. Journal of thoracic disease. 2017 Dec:9(12):5390-5398. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.11.14. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29312750]

Delling FN, Li X, Li S, Yang Q, Xanthakis V, Martinsson A, Andell P, Lehman BT, Osypiuk EW, Stantchev P, Zöller B, Benjamin EJ, Sundquist K, Vasan RS, Smith JG. Heritability of Mitral Regurgitation: Observations From the Framingham Heart Study and Swedish Population. Circulation. Cardiovascular genetics. 2017 Oct:10(5):. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.117.001736. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28993406]

Delling FN, Vasan RS. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of mitral valve prolapse: new insights into disease progression, genetics, and molecular basis. Circulation. 2014 May 27:129(21):2158-70. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.006702. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24867995]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKitkungvan D, Nabi F, Kim RJ, Bonow RO, Khan MA, Xu J, Little SH, Quinones MA, Lawrie GM, Zoghbi WA, Shah DJ. Myocardial Fibrosis in Patients With Primary Mitral Regurgitation With and Without Prolapse. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018 Aug 21:72(8):823-834. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.048. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30115220]

Gripari P, Mapelli M, Bellacosa I, Piazzese C, Milo M, Fusini L, Muratori M, Ali SG, Tamborini G, Pepi M. Transthoracic echocardiography in patients undergoing mitral valve repair: comparison of new transthoracic 3D techniques to 2D transoesophageal echocardiography in the localization of mitral valve prolapse. The international journal of cardiovascular imaging. 2018 Jul:34(7):1099-1107. doi: 10.1007/s10554-018-1324-2. Epub 2018 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 29484557]

Vahanian A, Urena M, Ince H, Nickenig G. Mitral valve: repair/clips/cinching/chordae. EuroIntervention : journal of EuroPCR in collaboration with the Working Group on Interventional Cardiology of the European Society of Cardiology. 2017 Sep 24:13(AA):AA22-AA30. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-17-00505. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28942383]

Parwani P,Avierinos JF,Levine RA,Delling FN, Mitral Valve Prolapse: Multimodality Imaging and Genetic Insights. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 2017 Nov - Dec [PubMed PMID: 29122631]

Slipczuk L, Rafique AM, Davila CD, Beigel R, Pressman GS, Siegel RJ. The Role of Medical Therapy in Moderate to Severe Degenerative Mitral Regurgitation. Reviews in cardiovascular medicine. 2016:17(1-2):28-39. doi: 10.3909/ricm0835. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27667378]

Adams DH, Rosenhek R, Falk V. Degenerative mitral valve regurgitation: best practice revolution. European heart journal. 2010 Aug:31(16):1958-66. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq222. Epub 2010 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 20624767]

Suri RM, Aviernos JF, Dearani JA, Mahoney DW, Michelena HI, Schaff HV, Enriquez-Sarano M. Management of less-than-severe mitral regurgitation: should guidelines recommend earlier surgical intervention? European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2011 Aug:40(2):496-502. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.11.068. Epub 2011 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 21257316]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHirata K,Triposkiadis F,Sparks E,Bowen J,Boudoulas H,Wooley CF, The Marfan syndrome: cardiovascular physical findings and diagnostic correlates. American heart journal. 1992 Mar [PubMed PMID: 1539526]

Scordo KA. Mitral valve prolapse syndrome health concerns, symptoms, and treatments. Western journal of nursing research. 2005 Jun:27(4):390-405; discussion 406-10 [PubMed PMID: 15870233]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceScordo KA. Factors associated with participation in a mitral valve prolapse support group. Heart & lung : the journal of critical care. 2001 Mar-Apr:30(2):128-37 [PubMed PMID: 11248715]

Scordo KA. Mitral valve prolapse syndrome. Nonpharmacologic management. Critical care nursing clinics of North America. 1997 Dec:9(4):555-64 [PubMed PMID: 9444178]

Mazine A,Friedrich JO,Nedadur R,Verma S,Ouzounian M,Jüni P,Puskas JD,Yanagawa B, Systematic review and meta-analysis of chordal replacement versus leaflet resection for posterior mitral leaflet prolapse. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2018 Jan [PubMed PMID: 28967416]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBayer-Topilsky T, Suri RM, Topilsky Y, Marmor YN, Trenerry MR, Antiel RM, Mahoney DW, Schaff HV, Enriquez-Sarano M. Mitral Valve Prolapse, Psychoemotional Status, and Quality of Life: Prospective Investigation in the Current Era. The American journal of medicine. 2016 Oct:129(10):1100-9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.05.004. Epub 2016 May 24 [PubMed PMID: 27235006]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence