Anesthesia Monitoring of Mixed Venous Saturation

Anesthesia Monitoring of Mixed Venous Saturation

Introduction

While oxygen saturation refers to the percentage of hemoglobin bound to oxygen within red blood cells, mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2) refers to the oxygen content of the blood that returns to the heart after meeting tissue needs. Therefore, in practice, venous oxygen saturation is a measured value that is a significant parameter when managing patients in the perioperative period, critical care setting, and patients presenting with shock pathophysiology. While its use as a therapeutic endpoint as part of early goal-directed therapy has received study with varying results, abnormal values have been invariably concluded to correlate with higher mortality. Therefore, monitoring mixed venous oxygen has significant value in risk stratification, prognosis, and monitoring to recognize tissue hypoxia in the critically ill. It is one of several parameters that should be considered when assessing adequate tissue perfusion.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Mixed venous oxygen saturation is so-called because it is the combination of venous blood from both the superior and inferior vena caval systems. Venous blood from the upper extremities and head returns to the heart via the superior vena cava (SVC), and venous blood from the lower extremities, renal, and splanchnic circulations returns to the heart via the inferior vena cava (IVC). Venous blood from both ends mixes within the right side of the heart to enter through the pulmonary artery to become oxygenated by the pulmonary circuit. Oxygenated blood, which contains oxyhemoglobin, enters the left heart through the pulmonary vein. Blood from the left side of the heart is pushed through the aorta into the systemic circulation to participate in gas exchange through vascular capillary beds. Venous blood now contains a relatively higher concentration of deoxyhemoglobin and returns to the venous system to be pushed through the heart again and oxygenated once more.

It is important to note that oxygen extraction occurs to different degrees between the upper and lower body. This is due to several factors, such as varying metabolic rates, blood flow, and oxygen consumption performed by different tissues. To illustrate this variation, venous oxygen saturation of specific organs has been estimated to be 37% for the heart versus 92% for the kidneys. With processes that cause more tissue oxygen demand, oxygen delivery can increase on multiple levels with increasing cardiac output, blood flow redistribution, and functional capillary density.[1]

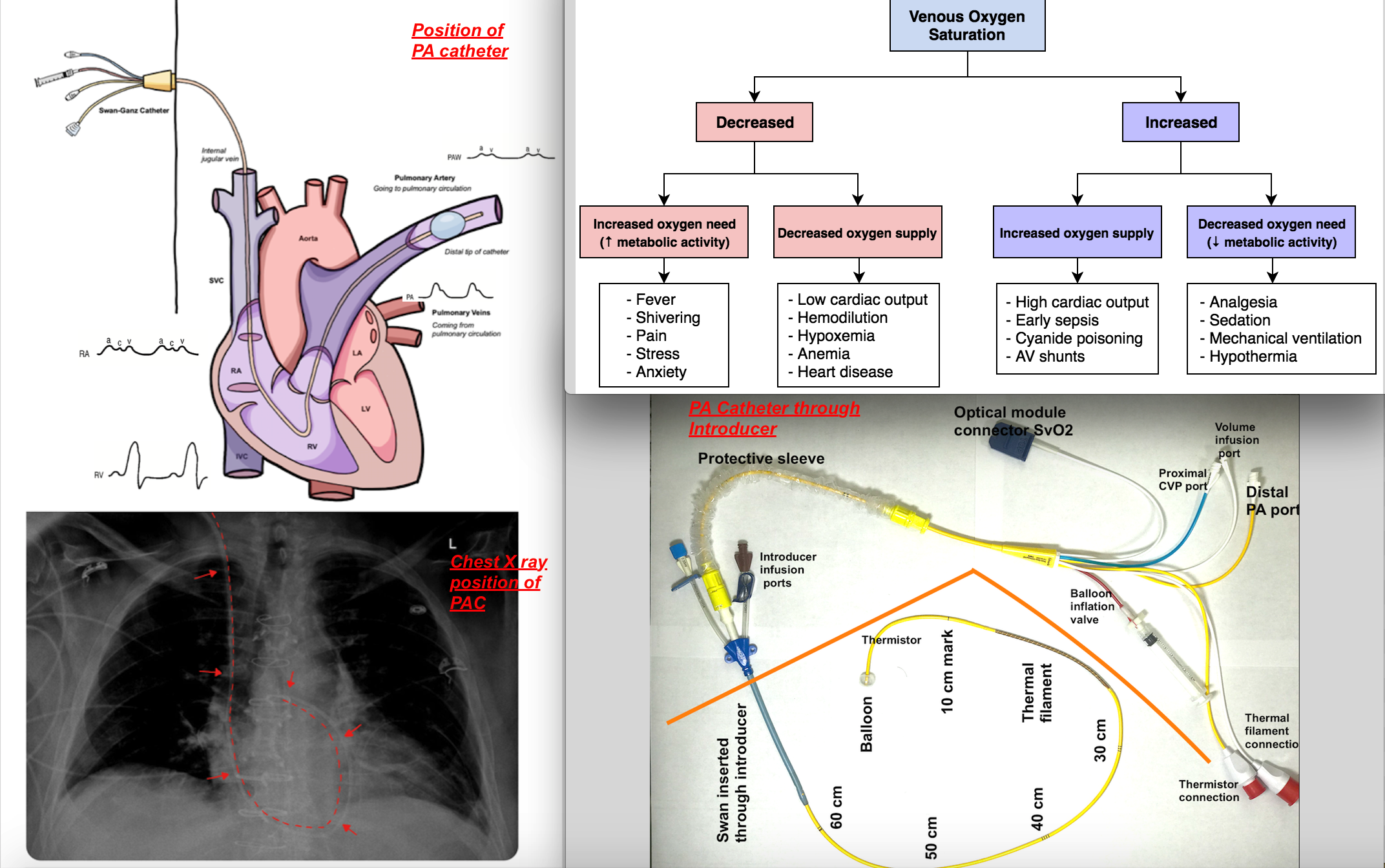

To measure mixed venous saturation, typically, a pulmonary artery catheter (PAC) is utilized and is introduced via a central venous catheter and positioned in the pulmonary artery [as shown in the accompanying image]. Pressure waveform changes guide the positioning of PAC as it traverses through the right atrium to the right ventricle to the pulmonary artery since each chamber has its typical pressure waveform profile [see attached image.]

Indications

Monitoring mixed venous oxygen saturation may be indicated in certain instances of patient care for monitoring, guiding therapy, and evaluating response to treatment. Such cases include the management of perioperative, critical care, heart failure, and septic patients. Therefore, it is crucial that any changes in the value of venous oxygen saturation undergo correct interpretation in a clinical scenario. Like any other monitoring technique, it is essential to integrate the numerical value of mixed venous saturation with other hemodynamic variables and to correlate the measured SvO2 with the patient's clinical situation.

Whenever there is a mismatch of oxygen demand and supply, such that there is an overall oxygen deficit at the level of the tissues, oxygen extraction will increase, leading to decreasing mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2). If such a mismatch exists and SvO2 decreases in the setting of increased oxygen demand, this could reflect the response to fever, shivering, pain, or stress with inadequate oxygen delivery compensation. When SvO2 decreases in the setting of decreased oxygen supply, this could reflect the response to anemia, hypoxemia, or reduced cardiac output during cardiogenic shock. When SvO2 increases in the setting of decreased oxygen demand, this could indicate a reaction to analgesia, sedation, mechanical ventilation, or hypothermia.[2]

When oxygen supply increases while venous oxygen saturation remains high (greater than 90%), this reflects impaired oxygen extraction, which is also unfavorable. Such is the case with reduced oxidative metabolism at the level of the mitochondria, leading to lactic acid accumulation and cell death. A possible scenario could be one in which cell damage has occurred, leading to impaired oxygen usage, as in the case of mitochondrial poisoning with cyanide. Other processes include septic shock or arteriovenous shunting, where flow is redistributed to areas of regional vasodilation. Similar trends can also present in instances of afterload reduction and cardiac function improvement.[3]

Contraindications

Since it is an invasive monitoring technique, the assessment of risk to benefit must take place in each patient. Contraindications for initial central venous cannulation include infection at the site of central venous insertion, coagulopathies that may lead to excessive bleeding, conditions that prevent correct Trendelenburg positioning, such as high intracranial pressure, or refusal to cooperate by the patient.[4] Furthermore, pulmonary artery catheterization is relatively contraindicated in the setting, including:

- Lack of skilled health care professional to place and maintain PAC (complications can happen during placement and malposition of catheter already placed)

- Patients with sensitivity to heparin

- Patients with latex allergy (use latex-free catheters if available )

- Tricuspid vegetation or mobile thrombus in the right heart (potential to embolize while placing PAC)

- Left bundle branch block (since a right bundle branch block during insertion of PAC can lead to complete heart block)

Equipment

To measure mixed venous saturation, a flow-directed pulmonary artery catheter is typically placed utilizing pressure waveform and/or fluoroscopy/echocardiographic guidance. The basis of the measurement is the physics principle of reflection spectrophotometry. The PAC capable of measuring continuous SvO2 has a fiberoptic transmission that receives and sends the signal to monitor and utilizes a LED photodetector that connects to the optical module on PAC, which typically displays a red light at the distal end of PAC. This monitoring system analyzes the saturation of red cells in blood flowing into the pulmonary artery.

Once a central vein has been localized, it is ready for cannulation. It is now the standard of care to use ultrasound guidance while inserting central venous catheters. A central venous catheter is inserted into the central vein with a finder needle, guide wire, and angiocath. To insert a pulmonary artery catheter, repeat the same steps but with the addition of an introducer, which serves as a point of entry for the pulmonary artery catheter (PAC) [see attached image]. Though this article concentrates on its utility in measuring mixed venous saturation, PACs also have several components to allow them to monitor cardiac output, central temperature, and pulmonary artery pressure and to infuse medication or fluids. The PAC design may vary by manufacturer but commonly entails a multi-lumen catheter.

The catheter that inserts into the body has several crucial segments. The blue proximal injectate port sits in the right atrium and can be used as a port to inject fluids or to monitor central venous pressures. Another port, known as a proximal infusion port, also sits in the right atrium and can be used to inject fluids and drugs. The thermistor usually lies within one of the pulmonary arteries proximal to the balloon tip. The yellow PA port leads to the distal lumen behind the balloon, which measures PA pressures and mixed venous oxygen saturation. The catheter that stays outside of the body is covered by a sterile cover and features valves for balloon inflation, thermistor connection, and distal and proximal injection sites. Caution must also be taken not to overinflate the PAC balloon, and no more than 1.5 ml of air should is put in the balloon.

During insertion and maintenance of the catheters, it is crucial to maintain sterility to prevent central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI). Every time the ports are accessed, they should be cleaned with an antiseptic to decrease the risk of contamination.

After the initial placement of the catheter, the depth at which PAC is secured should be noted, and the position should be confirmed by pressure waveform analysis as well as chest X-ray. Further, to avoid complications from misplacement, skilled providers should monitor patients.

Signal Quality index - the measured value of SvO2 should always be considered with signal quality index and is reported by automated machines typically varying from level 1 to 4, with 1 being a normal signal, 2 being moderately compromised, 3 being poor, and 4 being an unacceptable signal. Factors that compromise the signal quality include - the catheter tip against the wall of the pulmonary vessels, clotting at the tip of the catheter, and wedging of the catheter. Whenever SQI is high, that is a poor quality signal; the catheter position should be checked for migration or malposition and adjusted or recalibrated to get reliable SvO2 measurement. To recalibrate, mixed venous blood should slowly be drawn from the distal port of PAC and sent for venous gas analysis.

Personnel

The personnel involved in either a pulmonary artery or central venous catheterization should be trained to avoid possible complications of cannulation; this includes knowledge of proper positioning during initial cannulation as well as experience in recognizing signs of early complications that may arise after access. Also, other personnel should be prepared to identify and interpret data and waveforms obtained from monitoring hemodynamic changes. Improper or delayed interpretation of this diagnostic tool limits the application of any therapeutic regimen and may even lead to potential harm to patients.[5]

Experience with ultrasound guidance for inserting central venous catheters (CVC) and interpretation of pressure waveform and chest radiographs will help to confirm the location of the distal tip of catheters to prevent the erroneous placement of catheters. [see attached image for positioning of the catheter on chest X-ray]

Preparation

Before obtaining central venous access via catheterization, it is essential to regard strict aseptic technique, prep with chlorhexidine, and use sterile full-body barriers to reduce the risk of catheter-associated infection. Additionally, positioning is another important factor that affects the caliber of the veins to allow easier cannulation. In the Trendelenburg position, gravity allows the central venous filling to increase to produce a better-engorged vein and, ultimately, a larger target for access. The increased venous filling also helps to reduce the risk of air embolism.[6] Ultrasound guidance improves safety while inserting the catheter. Before insertion of the catheter, pressure transducers should be set up and connected to monitor to convert pressure tracing to meaningful values to aid placement and further patient monitoring and management.

Technique or Treatment

Venous oxygen saturation can be reliably measured at the pulmonary artery via a pulmonary artery catheter (PAC) or the superior vena cava (SVC) near the right atrium via a central venous catheter (CVC). The CVC is less costly and less invasive; however, it measures a surrogate value called central venous O2 saturation (ScvO2). Because the location of the distal tips of these catheters, and therefore the sampling sites, are in different locations, different saturation values will be measured. Recall that the CVC samples blood from the SVC, which predominantly reflects oxygen extraction from the head and upper extremities, neglecting the venous oxygen saturation of the lower body and abdominal organs. Meanwhile, the blood flow of the lower body tends to be allocated for non-oxidative phosphorylation, such as renal, portal, and hepatic circulation.[7]

Therefore, less oxygen extraction occurs in the lower body than in the upper body. Data from other studies suggest that venous oxygen saturation of blood returning from the SVC is estimated at around 70 to 75% and from the IVC approximately 75 to 80%; therefore, mixed venous oxygen saturation would present as a value between these two ranges. In adults, mixed venous oxygen returns to the heart with a residual 60 to 80% oxygen saturation.[1]

When a PAC is used, the sample blood is drawn slowly from the distal port in order to avoid inadvertent aspiration of oxygenated blood, leading to falsely elevated values of SvO2. CVC also has less potential for complications and allows for continuous monitoring that may prove useful when more frequent analysis is indicated. This catheter tip measures oxyhemoglobin content in venous blood via reflection spectrophotometry via fiber optics.[2]

ScvO2 tends to follow SvO2 trends, but ScvO2 maintains about 2 to 3% lower than SvO2. However, there are caveats to this rule. Different processes can change the relationship between these two values during different types of shock since there are changes in oxygen supply and demand.[2] During hypovolemic or cardiogenic shock, systemic circulation is redistributed to preserve brain perfusion, and mesenteric and renal perfusion becomes compromised. This leads to increased oxygen extraction despite decreased regional blood supply; therefore, this may produce a ScvO2 that may temporarily exceed SvO2 by nearly 20%.[1] Other discrepancies may present during septic shock, where local blood flow, oxygen-carrying capacity, and mitochondrial oxygen utilization may be altered. In these cases, ScvO2 can exceed SvO2 by nearly 8%.[8]

Complications

The use of catheters is not without complications, and usually, these risks are higher with the more invasive procedure associated with pulmonary artery catheterizations. Complications can result from inserting, manipulating, and maintaining pulmonary artery catheters (PAC). With initial insertion, thrombosis formation is one of the more common complications, with a thrombotic risk of internal jugular catheter placement being 7.6%. There are also relatively fewer common risks of arterial puncture, hematoma formation, AV fistula, thoracic duct injury, air embolization, and pneumothorax.

Furthermore, complications of PAC manipulation and maintenance include transient cardiac arrhythmias that happen with an incidence ranging between 12.5% to 70%, with PVCs and VTs being the most commonly observed. A catheter-associated infection is also an ongoing challenge, with the incidence of PAC-associated bacteremia being 1.3% to 2.3%. Cases of pulmonary artery rupture, chamber rupture, malposition in the coronary sinus, pulmonary infarction, and PAC knotting have been reported but are relatively rare.[9]

Clinical Significance

Since mixed venous measurement reflects the balance between oxygen delivery (DO2 ) and consumption (VO2 ), factors that affect its measurement include:

- Cardiac output (cardiac output = heart rate x stroke volume; can change with cardiogenic shock, congestive heart failure, left ventricular failure, valvular heart disease, arrhythmia, pacing, hypovolemia, sepsis-induced cardiac dysfunction, etc.)

- Hemoglobin (bleeding, hemorrhagic shock)

- Oxygenation (fraction of inspired oxygen, ventilatory mechanics, ARDS, etc.)

- Oxygen consumption (increased requirement from sepsis, shivering, burns, fever, pain, anxiety, increased work of breathing, etc.)

The benefits of mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2) and central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2) monitoring have shown mixed results from different randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses. The following include areas of continued research.

In sepsis, ScvO2 less than 70% or SvO2 lower than 65% correlate with poor prognosis.[2] In application, certain studies have shown that maintaining a goal ScvO2 greater than 70% leads to reduced mortality.[11] Therefore, ScvO2 is used to guide treatment algorithms in the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC). As part of initial resuscitation practice guidelines, SSC recommends achieving a ScvO2 of over 70% within the first 6 hours. However, this is not considered the standard of care and is rated a Grade 1c recommendation.[10]

Contradicting these results attempts to use ScvO2 as part of early goal-directed therapy (EGDT) in septic shock, as seen in the PROCESS trials, have not demonstrated benefit. TIn this s demonstrated no difference in all-cause mortality compared between protocol-based EGDT, which monitored ScvO2, and standard therapy, which monitored systolic blood pressure and shock index in patients with sepsis. Also, mixed venous oxygen saturation is an extremely broad parameter in that faulty oxygen utilization can stem from any level of failure from macro-circulatory to micro-circulatory to mitochondrial. Studies have shown that normal to higher levels of mixed venous oxygen saturation in patients with clinically worsening sepsis do not rule out tissue hypoxia due to the inability to utilize O2.[11][7] Therefore, several studies support the conclusion that abnormally low or high ScvO2 correlates with higher mortality in patients with septic shock.[12][13]

Low ScvO2 has associations with increased morbidity in the perioperative setting as well.[2] However, studies on the benefits of goal-directed therapy using ScvO2 have also shown mixed results. For example, one study found that hourly ScvO2 used in EGDT that maintained oxygen extraction of no more than 27% resulted in reduced incidences of organ failure and overall decreased hospital length of stay.[14] To support this further, a systematic review of 29 other RCTs has shown overall benefits on mortality and morbidity after surgery after using PACs as a part of guided-hemodynamic management.[15] However, studies also exist that show that there is no mortality benefit in monitoring via PAC.[16]

In the ICU, lower ScvO2 is heavily correlated with higher mortality than normoxic values of ScvO2. However, hemodynamic therapy aimed to normalize such values did not show to reduce morbidity or mortality.[2] In instances of hemorrhage, ScvO2 is an indicator of the patient’s circulatory status. As intravascular volume decreases, cardiac output falls, leading to increased oxygen extraction and decreased ScvO2. Monitoring persistently low ScvO2 even after adequate hemodynamic resuscitation may reflect cases of excessive hemodilution. Also, continuous ScvO2 monitoring has been proposed to assess CPR after initial resuscitation. ScvO2 less than 30% has been associated with failure to return to spontaneous circulation.[1] One Cochrane review states that SvO2 monitoring does not affect ICU or hospital length of stay, increases mean hospital costs per patient, and does not change mortality. However, it still recommends SvO2 as a diagnostic and hemodynamic monitoring tool to differentiate pathologic processes and guide patient care with proper interpretation.[5]

In heart failure cases, pump failure reduces oxygen delivery and increases tissue oxygen extraction. Therefore, continuous ScvO2 has been seen to guide treatment in patients with acute decompensation of heart failure.[1] A recent study showed that SvO2 monitoring allowed for more aggressive management in those with abnormal values since SvO2tightly correlates with cardiac output. The same study also showed that SvO2 was an early marker of decompensation. As a prognostic tool, ScvO2 lower than 60% is associated with poor outcomes in decompensated heart failure.[2] In a cohort study, ScvO2 was monitored in patients with ADHF to guide inotrope and diuretic support with the primary endpoint comparing major adverse cardiac events (MACE) defined by heart transplantation, cardiac assistance, and death. The study found that ScvO2 less than 60% in 24 hours demonstrated poor prognosis and was an independent predictor of MACE.[17]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Observing significant changes in mixed venous oxygen saturation indicates worsening prognosis in critically ill patients and should be one of the parameters used to assess adequate tissue perfusion. [Level I] Enhancing health outcomes for these patients who need venous monitoring is best accomplished through an interprofessional team-based approach, which includes clinicians, nursing staff, radiologists, and pharmacists. They all perform essential roles in sepsis, perioperative management, critical care, and heart failure by detecting sudden increases or decreases in oxygen delivery and extraction, and they must document their interventions while maintaining open lines of communication with other team members should they note any concerns. This interprofessional approach will yield optimal patient results. [Level 5]

When there is a clinical indication for mixed venous oxygen monitoring, the central line and swan catheter should be inserted under strict aseptic precaution. The site should be monitored daily to ensure it's clean and sterile. Only providers credentialed per institutional guidelines should be allowed to insert catheters since risks are significant and can be life-threatening. Once placed position should be confirmed, and the device should be secured and continuously monitored for misplacement. The clinical utility of the catheters is proven by providers trained to interpret data and waveforms. Finally, risks to benefits must be weighed for each patient, and like with any other invasive monitoring; PA catheter should be discontinued when no longer indicated in the management of the patient.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Image depicting position of Pulmonary artery catheter for hemodynamic monitoring, Chest Xray to verify position. Differential of mixed venuous saturation measurement. Components of PA catheter and placementof PA catheter through Introducer. Contributed by Dr. Chan Lee and Dr. Vaibhav Bora M.B.B.S. , FASE

References

Walton RAL,Hansen BD, Venous oxygen saturation in critical illness. Journal of veterinary emergency and critical care (San Antonio, Tex. : 2001). 2018 Sep; [PubMed PMID: 30071148]

Hartog C,Bloos F, Venous oxygen saturation. Best practice [PubMed PMID: 25480771]

Divertie MB,McMichan JC, Continuous monitoring of mixed venous oxygen saturation. Chest. 1984 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 6365478]

Kornbau C,Lee KC,Hughes GD,Firstenberg MS, Central line complications. International journal of critical illness and injury science. 2015 Jul-Sep; [PubMed PMID: 26557487]

Rajaram SS,Desai NK,Kalra A,Gajera M,Cavanaugh SK,Brampton W,Young D,Harvey S,Rowan K, Pulmonary artery catheters for adult patients in intensive care. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013 Feb 28; [PubMed PMID: 23450539]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBannon MP,Heller SF,Rivera M, Anatomic considerations for central venous cannulation. Risk management and healthcare policy. 2011; [PubMed PMID: 22312225]

van Beest P,Wietasch G,Scheeren T,Spronk P,Kuiper M, Clinical review: use of venous oxygen saturations as a goal - a yet unfinished puzzle. Critical care (London, England). 2011; [PubMed PMID: 22047813]

Marx G,Reinhart K, Venous oximetry. Current opinion in critical care. 2006 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 16672787]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVincent JL, The pulmonary artery catheter. Journal of clinical monitoring and computing. 2012 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 22886686]

Dellinger RP,Levy MM,Rhodes A,Annane D,Gerlach H,Opal SM,Sevransky JE,Sprung CL,Douglas IS,Jaeschke R,Osborn TM,Nunnally ME,Townsend SR,Reinhart K,Kleinpell RM,Angus DC,Deutschman CS,Machado FR,Rubenfeld GD,Webb S,Beale RJ,Vincent JL,Moreno R, Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive care medicine. 2013 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 23361625]

Vincent JL,Rhodes A,Perel A,Martin GS,Della Rocca G,Vallet B,Pinsky MR,Hofer CK,Teboul JL,de Boode WP,Scolletta S,Vieillard-Baron A,De Backer D,Walley KR,Maggiorini M,Singer M, Clinical review: Update on hemodynamic monitoring--a consensus of 16. Critical care (London, England). 2011 Aug 18 [PubMed PMID: 21884645]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYealy DM,Kellum JA,Huang DT,Barnato AE,Weissfeld LA,Pike F,Terndrup T,Wang HE,Hou PC,LoVecchio F,Filbin MR,Shapiro NI,Angus DC, A randomized trial of protocol-based care for early septic shock. The New England journal of medicine. 2014 May 1; [PubMed PMID: 24635773]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePope JV,Jones AE,Gaieski DF,Arnold RC,Trzeciak S,Shapiro NI, Multicenter study of central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO(2)) as a predictor of mortality in patients with sepsis. Annals of emergency medicine. 2010 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 19854541]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDonati A,Loggi S,Preiser JC,Orsetti G,Münch C,Gabbanelli V,Pelaia P,Pietropaoli P, Goal-directed intraoperative therapy reduces morbidity and length of hospital stay in high-risk surgical patients. Chest. 2007 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 17925428]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHamilton MA,Cecconi M,Rhodes A, A systematic review and meta-analysis on the use of preemptive hemodynamic intervention to improve postoperative outcomes in moderate and high-risk surgical patients. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2011 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 20966436]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSandham JD,Hull RD,Brant RF,Knox L,Pineo GF,Doig CJ,Laporta DP,Viner S,Passerini L,Devitt H,Kirby A,Jacka M, A randomized, controlled trial of the use of pulmonary-artery catheters in high-risk surgical patients. The New England journal of medicine. 2003 Jan 2; [PubMed PMID: 12510037]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGallet R,Lellouche N,Mitchell-Heggs L,Bouhemad B,Bensaid A,Dubois-Randé JL,Gueret P,Lim P, Prognosis value of central venous oxygen saturation in acute decompensated heart failure. Archives of cardiovascular diseases. 2012 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 22369912]