Introduction

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) encompasses several imaging techniques based on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) developed for studying the arterial and venous systems. The benefits of an MRA in comparison to traditional angiography is that it is noninvasive, it lacks ionizing radiation exposure, it has the potential for a non-contrast examination, and it has the ability of high-resolution volumetric images. The MRA gadolinium contrast material is less likely to cause an allergic reaction than the iodine-based contrast materials used for computed tomography scanning. In this review, the different techniques for MRA are discussed, and the indications for different pathologies are disclosed.

Indications

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Indications

An MRA is used to evaluate the following abnormalities:

- Arterial aneurysm[1]

- Arteriovenous malformations[2][3][4]

- Aortic coarctation[1]

- Aortic dissection[5][6]

- Cerebral stroke[1]

- Carotid artery disease[7][8]

- Peripheral (extremity) atherosclerosis[1]

- Congenital heart disease[1]

- Coronary artery disease and graft patency[9][10][11][12]

- Mesenteric artery ischemia[13][14]

- Renal artery stenosis[15]

- Pulmonary embolism[16][17]

- Trigeminal neuralgia[18][19][20]

- Moyamoya disease[21][22]

- Screening [1][23][24]

- Monitoring[1]

Contraindications

MRA has the same contraindications as for the MRI exam without contrast medium. MRA does not use radiation, and to date, side effects from the magnetic fields and radio-waves have not been reported. Gadolinium-based contrast agents can cross the placenta; therefore, it should not be administered during pregnancy, particularly during the first trimester.[25] It has been shown that patients with gadolinium exposure can present gadolinium deposition in the brain, especially in the dentate nuclei and globus pallidus, but no clinical consequences specific to neurological toxicity have been demonstrated.[26]

Non-contrast Study

Absolute contraindication: A cardiac implantable electronic device, mechanical metallic heart valves, metallic foreign bodies, implantable neurostimulation system, cochlear implants/ear implant, non-removable drug infusion pumps, catheters with metallic components, cerebral artery aneurysm clips which are non-MRI compatible, tissue expanders with magnetic infusion ports.

Relative contraindications: Coronary and peripheral artery stents, programmable shunts, airway stents, intrauterine devices, ocular prosthesis, stapes implants, surgical clips, or wire sutures, penile prosthesis, recent joint replacement or prosthesis, inferior vena cava filter, physical limitations, and non-removable piercings.

Contrast Medium

Absolute contraindications: Patients who had a previous allergic or anaphylactic reaction to gadolinium, or patients who have a glomerular filtration rate below 30 mL/min/1.73 m^2.[27]

Relative contraindications: A history of renal disease and dialysis. Patients with impaired renal function are at risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF), which was previously called nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. Pregnancy is also a relative contraindication.[28]

Technique or Treatment

MRA is a term that groups various imaging techniques based on different physical principles and is employed for diverse diagnostic purposes. MRA techniques can be categorized into "non-contrast" and "contrast-enhanced" techniques.[29][30]

Non-contrast MRA

Non-contrast media techniques can be further divided into two groups according to the blood signal characteristics:

- Black–blood sequences (or dark-blood), in which the intravascular signal is lower than that of the surrounding stationary tissues.[31]

- Bright–blood sequences (or white-blood), where the intravascular signal is higher than that of the surrounding stationary tissues.[32]

Black–blood sequences: Black-blood sequences are not used in the routine evaluation of the peripheral vasculature, but they are essential in specific clinical scenarios, such as vasculitis, cardiac imaging, and susceptibility venography. The rapidly flowing blood has a naturally low signal because of phase-dispersion and time-of-flight signal losses. This is evident in the vascular "flow voids" artifact commonly found on routine MRI that represents a raw form of dark-blood MRA. To evaluate the vessel wall in vasculitis, the combination of black-blood sequences pre-contrast and post-contrast T1 weighted are the gold standard.

This effect is extremely accentuated in black-blood sequences by the application of specific procedures:

- Short Repetition Time (TR): The blood signal is saturated because of its long T1.

- Medium Echo Time (TE): At 20 to 30 seconds TE, the protons in movement inside the blood vessel are dephased.

- Inversion Recovery (IR): The inversion time is set to reduce the signal intensity of the incoming blood.

- Spatial Saturation: A series of techniques used to produce the signal saturation of the blood outside the volume under examination.

- Gradient Dephasing: Increasing the movement-induced dephasement of the blood protons inside the vessels.

- 90° to 180° Wash-out: On spin-echo sequences, the signal of the protons of the blood leaving the voxel under analysis in the time included between the application of the 90° and 180° radio-frequency (RF) pulse and at 180° is lost.

Bright–blood sequences: These sequences are optimal for the study of the vascular lumen, but they have less accuracy in the evaluation of the vessel wall in comparison to dark-blood techniques.[33][34] This kind of sequence is characterized by very low TR and amplifies the transverse magnetization of the protons of the moving blood by the use of additional gradients, resulting in sequence with a high intravascular signal and fast acquisition.

Time of Flight (TOF) Technique

The TOF technique is based on the "inflow effect." When protons are subjected to RF pulses applied at very short repetition times (RT), the signal derived from them will be zero, because of the constant saturation of their longitudinal magnetization. The blood protons entering the acquisition volume aren't subjected to this saturation, and therefore they release a high signal, determining vascular enhancement related to the "inflow effect." Stair-step artifact in which the image shows a pixelated appearance to obliquely oriented vessels is caused because the slices in 2D are relatively thick (1mm to 3 mm) compared to the in-plane spatial resolution of 0.5 mm to 1.0 mm. They can be minimized by overlapping slices, however, with an important increase in scan time.

This technique represents the first diagnostic choice for the study of intracranial circulation and the second choice for the epi-aortic vessels when a study with a contrast medium cannot be performed. It allows the study of vessels at high flow speed, such as arteries, and it ignores much of the signal coming from the veins. Images are susceptible to motion artifacts and to protons dephasing related to very slow flow velocity as observed in severe stenosis or tortuosity in vessels, with the risk of an overestimation of the degree of stenosis. TOF can be performed with 2D and 3D acquisitions. 2D acquisitions are particularly sensible to proton dephasing artifacts with the very slow flows at the level of vascular stenosis. In peripheral MR angiography, flow is oriented craniocaudally, and two-dimensional (2D) TOF has is an accurate method to diagnose peripheral vascular disease and cervical carotid disease.[32] The introduction of the 3D acquisitions resulted in a noticeable increase in diagnostic accuracy.

Phase-Contrast (PC) Technique

The physical basis of the PC technique is the application of a couple of bipolar gradients that sequentially phase/dephase the proton spins into the acquisition volume. The signal intensity of the pixels is directly related to the values of the speed protons of the blood moving in the volume of interest, with the complete saturation of the static tissue signal.

By selecting the correct speed encoding parameters (VElocity ENCoding, VENC), it is possible to obtain selective imaging of the arterial vessels (VENC factor > 40 cm/sec) and of the veins (VENC factor < 20 cm/sec). It can create a venogram with an accurate study of the low-speed flowing vessels. Its use is limited by the extremely long acquisition times.[32] The use of PC is restricted to the study of the intracranial circulation (particularly the venous system), while in other anatomic regions, the application is limited.

Several newer non-contrast techniques/sequences are frequently used:

Hybrid of Opposite-contrast (HOP-MRA)

The HOP-MRA method is an extension of 3D TOF. The HOP-MRA pulse sequence uses flow-compensated echo acquisition, similar to conventional 3D TOF. Because it is fundamentally a 3D TOF, it detects fast-flowing blood better than slow-flowing blood. Dark-blood image better depicts slow-flowing spins. Bright-blood and dark-blood images are combined to yield a final angiogram and are able to depict vessels with both fast- and slow-flowing blood.[33] Fine cerebral vessels like those in moyamoya disease are clearly visualized.

Quiescent Interval Single-shot (QISS)

QISS is an inflow-based MRA which relies on a presaturation RF pulse. Following the presaturation, "quiescent interval" (QI), fresh inflowing blood enters the saturated slice.[33] A common application is for run-off studies in peripheral arteries.

Electrocardiographically (cardiac) ECG-gated 3D Partial-Fourier Fast Spin-echo FSE

This MRA technique relies on an ECG-gated 3D partial Fourier FSE sequence, which is triggered for systolic and diastolic acquisitions.[33] This relies on the loss of signal, or flow void, as a result of fast arterial flow during systole. In contrast, during diastole, the slow flow in arteries causes them to have high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. Because of its relatively slow flow, venous blood is bright during both systole and diastole. Bright-blood MR angiography is then achieved by subtracting systolic from diastolic images. It is used for aorta, pulmonary, and peripheral imaging.

Balanced Steady-state Free Precession (SSFP)

Balanced SSFP without arterial spin labeling (ASL) can be performed with ECG gating for thoracic aortic MRA and with both ECG gating and navigator-gated free-breathing for whole-heart coronary artery MRA.[32] In this technique, the image contrast is determined by T2/T1 ratios, which produce bright-blood imaging without reliance on inflow. ASL can be utilized and relied on the spin tagging upstream of the arteries of interest by using an inversion pulse to generate image contrast. It is used for pulmonary, carotid, renal, and distal peripheral MRA.[32][33]

Four-Dimensional PC-MRA (4D Flow)

This technique generates time-resolved 3D PC flow maps acquired with cine mode ECG gating and allows the evaluation of regional aortic flow characteristics.[33]

Flow-sensitive Dephasing (FSD)

In this technique, the flow-induced phase generated by the bipolar gradients is not used for flow-encoding, but rather flow-dephasing.[33]

Contrast-enhanced (CE) MRA

CE MRA is based on the vascular enhancement of T1 sequences thanks to the paramagnetic contrast agent gadolinium. The contrast medium represents the main difference between CE MRA and the other MRA techniques based on flow physical properties. For this reason, this technique is very low influenced by dephasing artifacts that are seen in the other MRA techniques.[29][35]

The MRI sequences used in CE MRA are very rapid gradient echo, which is sensitive to the T1 shortening due to gadolinium. For this reason, this technique is very dependent on the correct timing of the arrival of the bolus of contrast agent in the vessels. The plane of acquisition should be as close as possible to the plane of the vessel studied. For this reason, the coronal plane is usually preferred, while in TOF, the acquisition plane is usually orthogonal to the vessel of interest.

Two CE-MRA techniques are used:

- Elliptical-centric: The acquisition begins as the contrast agent enters the artery of interest with the use of an automatic bolus detection software or by determining the time it takes the gadolinium to reach the artery of interest.

- Multiphase Techniques: When the bolus is injected, multiple acquisitions are made to cover different phases (early arterial phase, late arterial phase, hepatic or late portal phase, nephrogenic phase, delayed phase).[36] One of the limitations of multiphase imaging is the loss of the spatial resolution to get a high temporal resolution. To increase the spatial resolution of the multiphase exam, the central region of the k-space rich in the MRI signal is acquired more often than the outer parts of k-space. This technique is defined as "time-resolved imaging of contrast kinetics" (TRICKS). In TRICKS, the 3D k-space is divided into subvolumes located at different distances from a central core subvolume. This central region of k-space is oversampled while the outer areas have a lower sampling rate. In this way, TRICKS can consistently capture the arterial phase free of the venous component.[37]

Complications

MRA has similar complications as with MRI exams. A meta-analysis of 716,978 contrast-enhanced MRI exams from 9 studies revealed an overall rate of allergic-like reactions of 9.2 per 10,000 administrations, and a rate of severe allergic-like reactions was 0.52 per 10,000 administrations.[38]

A recent study reviewed the MRI-related adverse event reports received by the Food and Drug Administration during a 10-year period.[39] A total of 1,548 adverse events were recorded, which were divided into eight different categories.

- Thermal: Skin reddening, blisters, warming, or heating sensation;

- Acoustic: Hearing loss and/or tinnitus;

- Image Quality: Lost exams, inadequate images, or images attributed to the incorrect patient;

- Projectile: Objects were pulled into or attracted to the main static magnetic field;

- Mechanical: Falls, crush injuries, broken bones, cuts, or musculoskeletal injuries;

- Peripheral Nerve Stimulation: Nerve or muscle stimulation or patients experiencing tingling, twitching, or involuntary movements;

- Miscellaneous: Adverse event that can not be classified in any of the other categories;

- Unclear: Insufficient information was available to make conclusions regarding the connection to the MRI exam.

Clinical Significance

MRA offers a noninvasive alternative to conventional angiography in patients with suspected or confirmed vascular pathologies. For this reason, MRA is an imaging method that has long become an essential part of the common clinical routine.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An MRA scan takes less time than traditional catheter angiography and requires no recovery period. MRA is less costly than catheter angiography. Collaboration with shared indication and decision making and communication are key elements for a good outcome. The MRA is usually recommended by a specialist treating a specific disorder. It is important to orient the patient about the procedure as some patients are afraid of the machine or have physical limitations. Some patients are unable to lie flat or stay in the position for a long period of time.

It is very important for the referring physician to clearly annotate the indications for the study, so the neuroradiologist and MRA technician performs the preferred technique to yield the best diagnostic outcomes.

Media

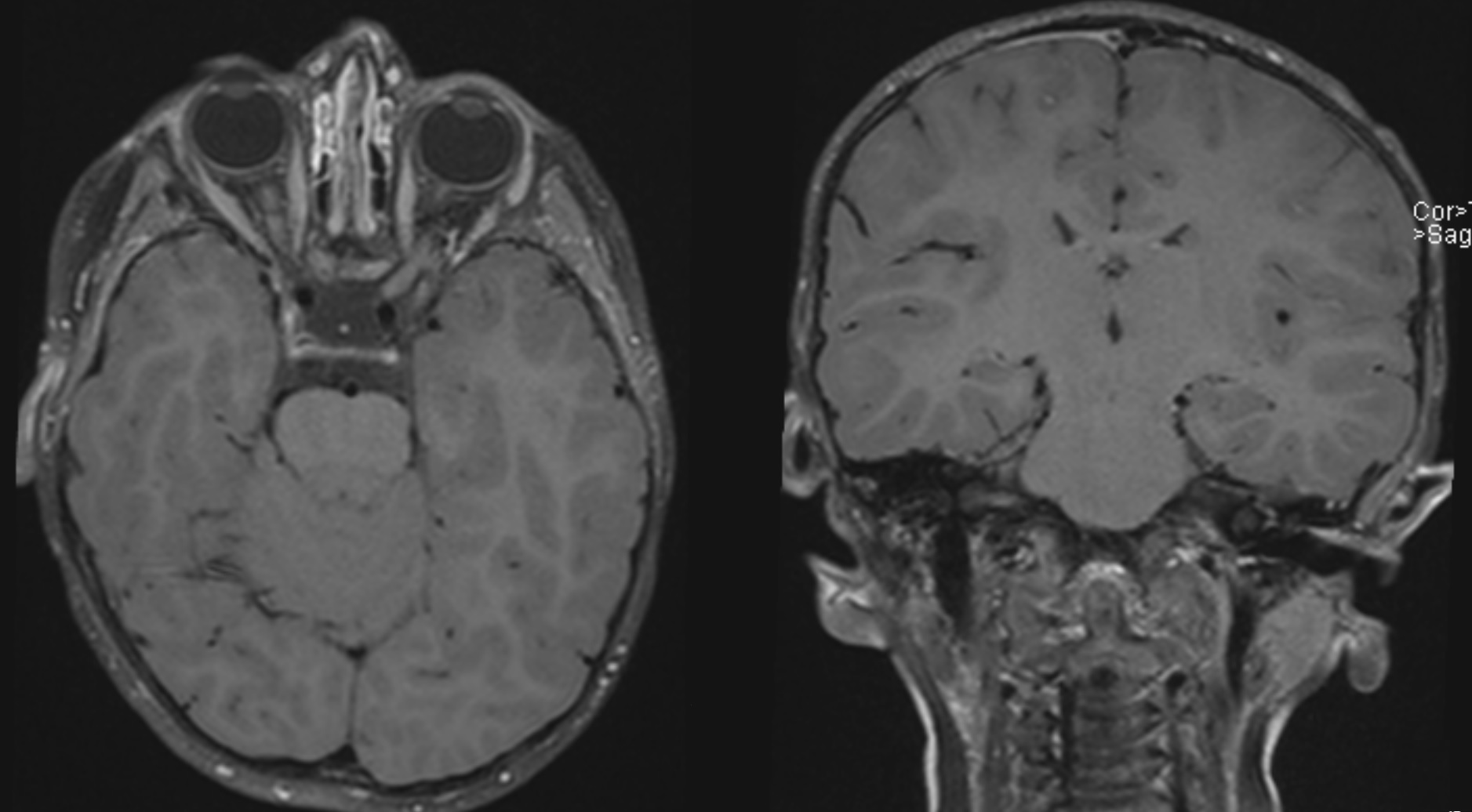

(Click Image to Enlarge)

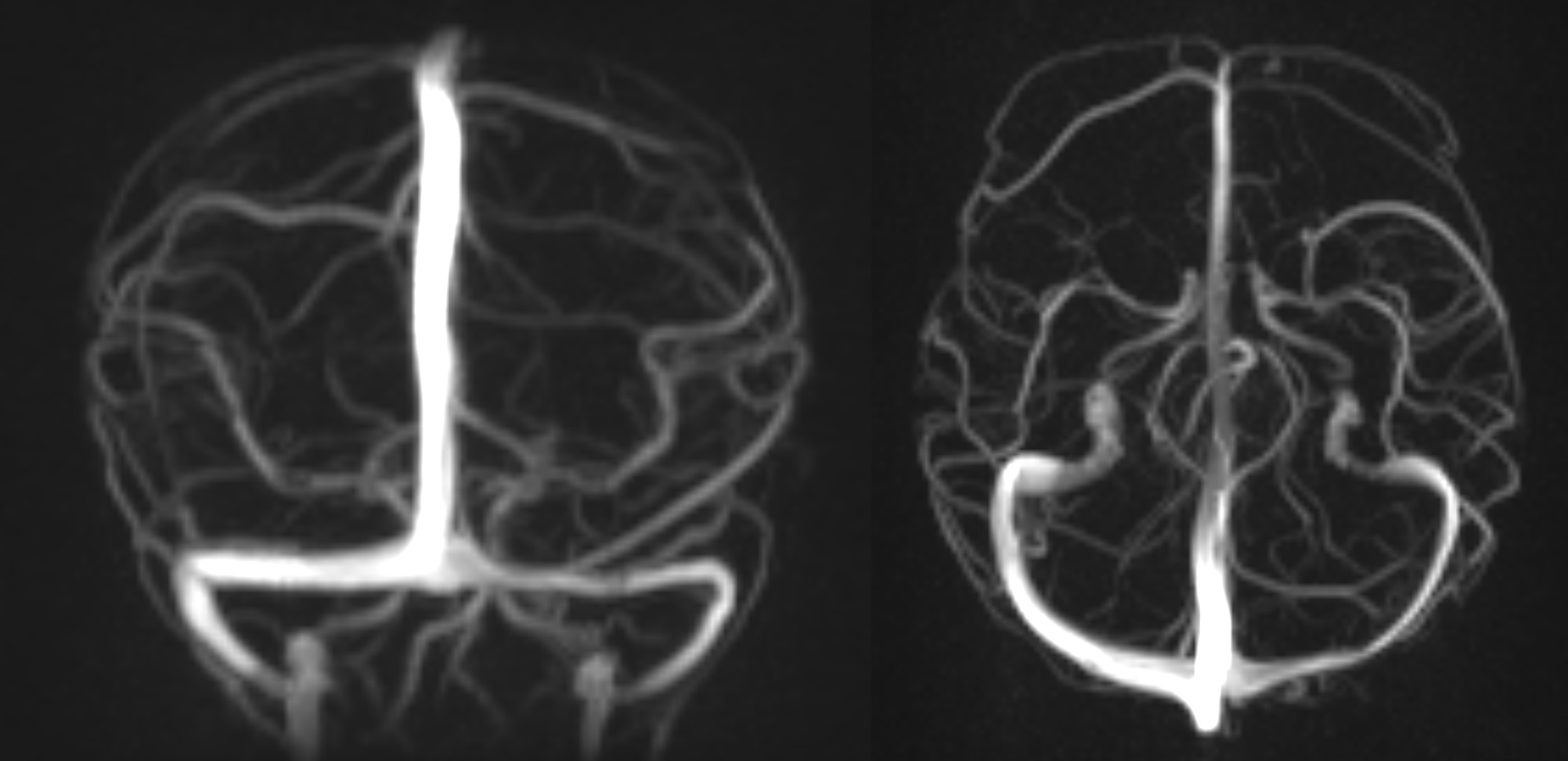

(Click Image to Enlarge)

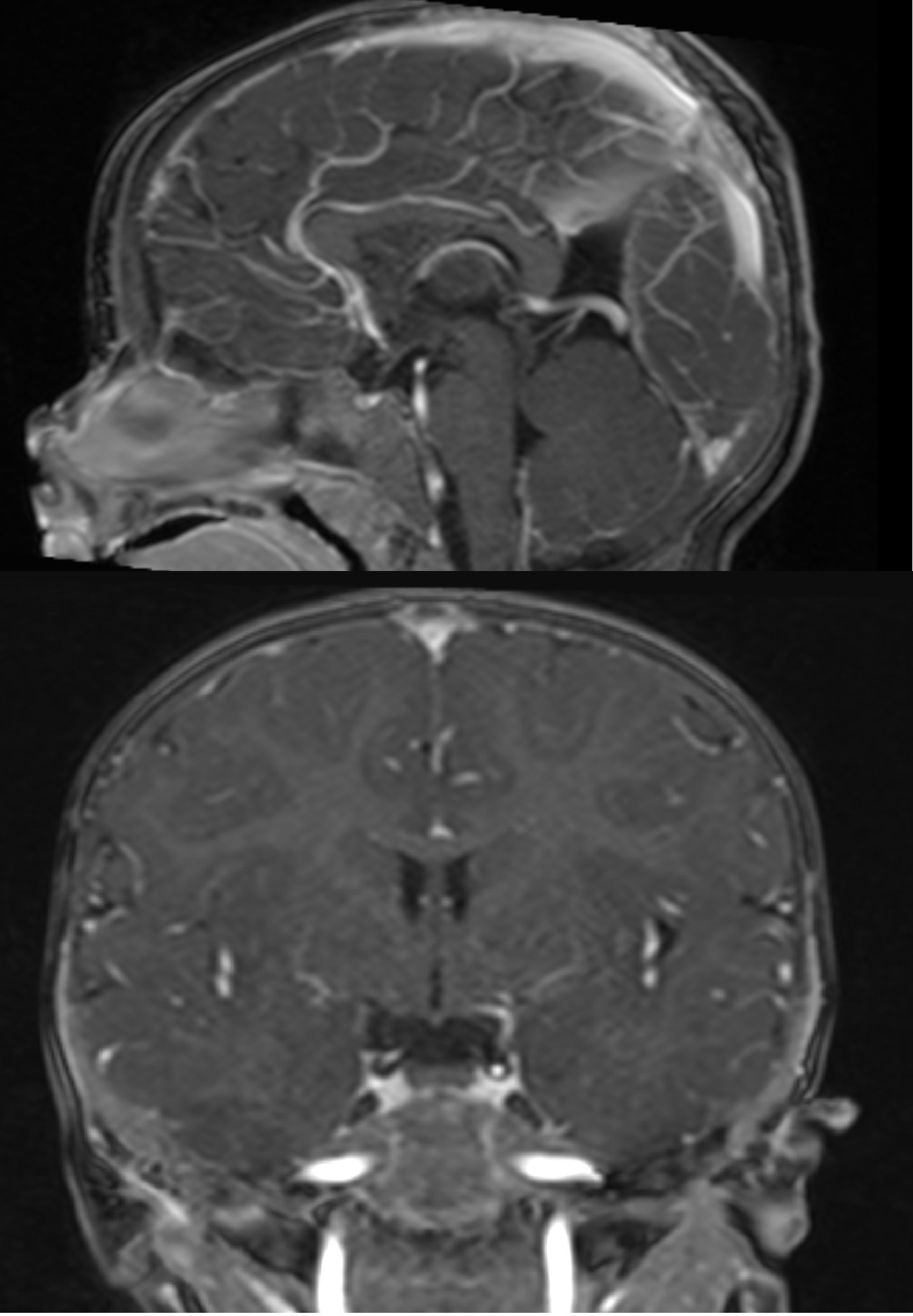

(Click Image to Enlarge)

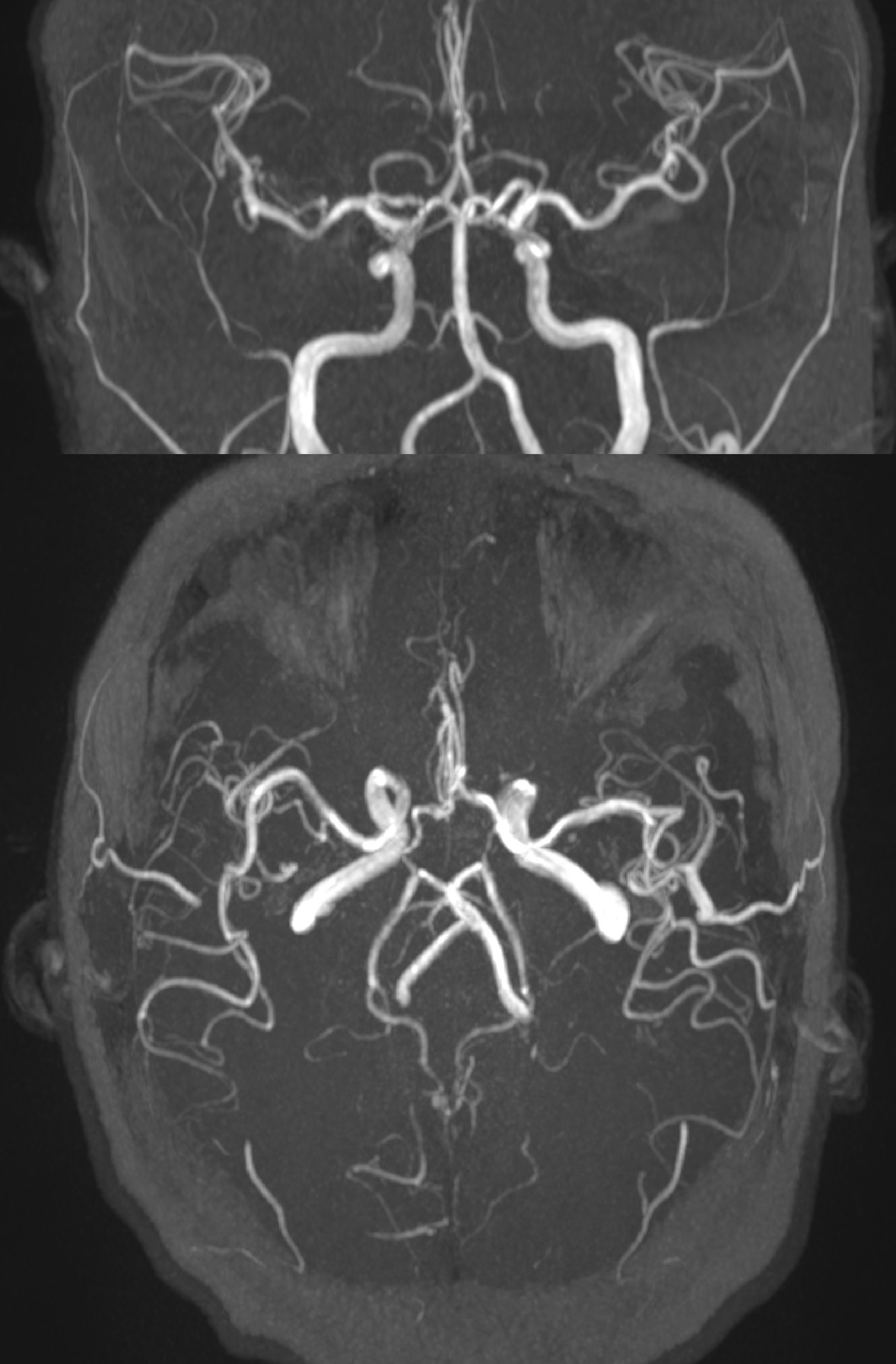

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Lim RP, Koktzoglou I. Noncontrast magnetic resonance angiography: concepts and clinical applications. Radiologic clinics of North America. 2015 May:53(3):457-76. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2014.12.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25953284]

Arai N, Akiyama T, Fujiwara K, Koike K, Takahashi S, Horiguchi T, Jinzaki M, Yoshida K. Silent MRA: arterial spin labeling magnetic resonant angiography with ultra-short time echo assessing cerebral arteriovenous malformation. Neuroradiology. 2020 Apr:62(4):455-461. doi: 10.1007/s00234-019-02345-3. Epub 2020 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 31898767]

Brunozzi D, Hussein AE, Shakur SF, Linninger A, Hsu CY, Charbel FT, Alaraj A. Contrast Time-Density Time on Digital Subtraction Angiography Correlates With Cerebral Arteriovenous Malformation Flow Measured by Quantitative Magnetic Resonance Angiography, Angioarchitecture, and Hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 2018 Aug 1:83(2):210-216. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyx351. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29106647]

Cheng YC, Chen HC, Wu CH, Wu YY, Sun MH, Chen WH, Chai JW, Chi-Chang Chen C. Magnetic Resonance Angiography in the Diagnosis of Cerebral Arteriovenous Malformation and Dural Arteriovenous Fistulas: Comparison of Time-Resolved Magnetic Resonance Angiography and Three Dimensional Time-of-Flight Magnetic Resonance Angiography. Iranian journal of radiology : a quarterly journal published by the Iranian Radiological Society. 2016 Apr:13(2):e19814. doi: 10.5812/iranjradiol.19814. Epub 2016 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 27679690]

Baliga RR, Nienaber CA, Bossone E, Oh JK, Isselbacher EM, Sechtem U, Fattori R, Raman SV, Eagle KA. The role of imaging in aortic dissection and related syndromes. JACC. Cardiovascular imaging. 2014 Apr:7(4):406-24. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.10.015. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24742892]

Kinner S, Eggebrecht H, Maderwald S, Barkhausen J, Ladd SC, Quick HH, Hunold P, Vogt FM. Dynamic MR angiography in acute aortic dissection. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI. 2015 Aug:42(2):505-14. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24788. Epub 2014 Nov 28 [PubMed PMID: 25430957]

Fellner C, Lang W, Janka R, Wutke R, Bautz W, Fellner FA. Magnetic resonance angiography of the carotid arteries using three different techniques: accuracy compared with intraarterial x-ray angiography and endarterectomy specimens. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI. 2005 Apr:21(4):424-31 [PubMed PMID: 15779039]

Saxena A, Ng EYK, Lim ST. Imaging modalities to diagnose carotid artery stenosis: progress and prospect. Biomedical engineering online. 2019 May 28:18(1):66. doi: 10.1186/s12938-019-0685-7. Epub 2019 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 31138235]

Hajhosseiny R, Bustin A, Munoz C, Rashid I, Cruz G, Manning WJ, Prieto C, Botnar RM. Coronary Magnetic Resonance Angiography: Technical Innovations Leading Us to the Promised Land? JACC. Cardiovascular imaging. 2020 Dec:13(12):2653-2672. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.01.006. Epub 2020 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 32199836]

Dai JW, Cao J, Lin L, Li X, Wang YN, Jin ZY. [Feasibility of Non-contrast-enhanced Coronary Magnetic Resonance Angiography at 3.0T]. Zhongguo yi xue ke xue yuan xue bao. Acta Academiae Medicinae Sinicae. 2020 Apr 28:42(2):216-221. doi: 10.3881/j.issn.1000-503X.11295. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32385028]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHenningsson M, Shome J, Bratis K, Vieira MS, Nagel E, Botnar RM. Diagnostic performance of image navigated coronary CMR angiography in patients with coronary artery disease. Journal of cardiovascular magnetic resonance : official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2017 Sep 11:19(1):68. doi: 10.1186/s12968-017-0381-3. Epub 2017 Sep 11 [PubMed PMID: 28893296]

Kato Y, Ambale-Venkatesh B, Kassai Y, Kasuboski L, Schuijf J, Kapoor K, Caruthers S, Lima JAC. Non-contrast coronary magnetic resonance angiography: current frontiers and future horizons. Magma (New York, N.Y.). 2020 Oct:33(5):591-612. doi: 10.1007/s10334-020-00834-8. Epub 2020 Apr 2 [PubMed PMID: 32242282]

van Dijk LJ, van Petersen AS, Moelker A. Vascular imaging of the mesenteric vasculature. Best practice & research. Clinical gastroenterology. 2017 Feb:31(1):3-14. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2016.12.001. Epub 2017 Jan 5 [PubMed PMID: 28395786]

Hagspiel KD, Flors L, Hanley M, Norton PT. Computed tomography angiography and magnetic resonance angiography imaging of the mesenteric vasculature. Techniques in vascular and interventional radiology. 2015 Mar:18(1):2-13. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2014.12.002. Epub 2014 Dec 29 [PubMed PMID: 25814198]

Guo X, Gong Y, Wu Z, Yan F, Ding X, Xu X. Renal artery assessment with non-enhanced MR angiography versus digital subtraction angiography: comparison between 1.5 and 3.0 T. European radiology. 2020 Mar:30(3):1747-1754. doi: 10.1007/s00330-019-06440-0. Epub 2019 Dec 3 [PubMed PMID: 31797079]

Pressacco J, Papas K, Lambert J, Paul Finn J, Chauny JM, Desjardins A, Irislimane Y, Toporowicz K, Lanthier C, Samson P, Desnoyers M, Maki JH. Magnetic resonance angiography imaging of pulmonary embolism using agents with blood pool properties as an alternative to computed tomography to avoid radiation exposure. European journal of radiology. 2019 Apr:113():165-173. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2019.02.007. Epub 2019 Feb 11 [PubMed PMID: 30927943]

Ley S, Kauczor HU. MR imaging/magnetic resonance angiography of the pulmonary arteries and pulmonary thromboembolic disease. Magnetic resonance imaging clinics of North America. 2008 May:16(2):263-73, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2008.02.012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18474331]

Hao YB, Zhang WJ, Chen MJ, Chai Y, Zhang WH, Wei WB. Sensitivity of magnetic resonance tomographic angiography for detecting the degree of neurovascular compression in trigeminal neuralgia. Neurological sciences : official journal of the Italian Neurological Society and of the Italian Society of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2020 Oct:41(10):2947-2951. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04419-0. Epub 2020 Apr 29 [PubMed PMID: 32346806]

Gamaleldin OA, Donia MM, Elsebaie NA, Abdelkhalek Abdelrazek A, Rayan T, Khalifa MH. Role of Fused Three-Dimensional Time-of-Flight Magnetic Resonance Angiography and 3-Dimensional T2-Weighted Imaging Sequences in Neurovascular Compression. World neurosurgery. 2020 Jan:133():e180-e186. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.08.190. Epub 2019 Sep 4 [PubMed PMID: 31493603]

Docampo J, Gonzalez N, Muñoz A, Bravo F, Sarroca D, Morales C. Neurovascular study of the trigeminal nerve at 3 t MRI. The neuroradiology journal. 2015 Feb:28(1):28-35. doi: 10.15274/NRJ-2014-10116. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25924169]

Savolainen M, Pekkola J, Mustanoja S, Tyni T, Hernesniemi J, Kivipelto L, Tatlisumak T. Moyamoya angiopathy: radiological follow-up findings in Finnish patients. Journal of neurology. 2020 Aug:267(8):2301-2306. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09837-w. Epub 2020 Apr 22 [PubMed PMID: 32322979]

Lehman VT, Cogswell PM, Rinaldo L, Brinjikji W, Huston J, Klaas JP, Lanzino G. Contemporary and emerging magnetic resonance imaging methods for evaluation of moyamoya disease. Neurosurgical focus. 2019 Dec 1:47(6):E6. doi: 10.3171/2019.9.FOCUS19616. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31786551]

Malhotra A, Wu X, Matouk CC, Forman HP, Gandhi D, Sanelli P. MR Angiography Screening and Surveillance for Intracranial Aneurysms in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease: A Cost-effectiveness Analysis. Radiology. 2019 May:291(2):400-408. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019181399. Epub 2019 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 30777807]

Nielsen R, Hauerberg J, Munthe S, Nielsen TH, Rochat P, Birkeland P, Rudnicka S, Gulisano HA, Sehested T, Diaz A, Karabegovic S, Sunde N. [Screening for intracranial aneurysms]. Ugeskrift for laeger. 2019 Jan 7:181(2):. pii: V05180375. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30618370]

Alorainy IA, Albadr FB, Abujamea AH. Attitude towards MRI safety during pregnancy. Annals of Saudi medicine. 2006 Jul-Aug:26(4):306-9 [PubMed PMID: 16885635]

Mallio CA, Rovira À, Parizel PM, Quattrocchi CC. Exposure to gadolinium and neurotoxicity: current status of preclinical and clinical studies. Neuroradiology. 2020 Aug:62(8):925-934. doi: 10.1007/s00234-020-02434-8. Epub 2020 Apr 21 [PubMed PMID: 32318773]

Kitajima K, Maeda T, Watanabe S, Ueno Y, Sugimura K. Recent topics related to nephrogenic systemic fibrosis associated with gadolinium-based contrast agents. International journal of urology : official journal of the Japanese Urological Association. 2012 Sep:19(9):806-11. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2012.03042.x. Epub 2012 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 22571387]

Ghadimi M, Sapra A. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Contraindications. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31869133]

Maki JH, Chenevert TL, Prince MR. Contrast-enhanced MR angiography. Abdominal imaging. 1998 Sep-Oct:23(5):469-84 [PubMed PMID: 9841060]

Miyazaki M, Isoda H. Non-contrast-enhanced MR angiography of the abdomen. European journal of radiology. 2011 Oct:80(1):9-23. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.01.093. Epub 2011 Feb 16 [PubMed PMID: 21330081]

Jara H, Barish MA. Black-blood MR angiography. Techniques, and clinical applications. Magnetic resonance imaging clinics of North America. 1999 May:7(2):303-17 [PubMed PMID: 10382163]

Miyazaki M, Lee VS. Nonenhanced MR angiography. Radiology. 2008 Jul:248(1):20-43. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2481071497. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18566168]

Wheaton AJ, Miyazaki M. Non-contrast enhanced MR angiography: physical principles. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI. 2012 Aug:36(2):286-304. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23641. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22807222]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKrishnamurthy R, Malone L, Lyons K, Ketwaroo P, Dodd N, Ashton D. Body MR angiography in children: how we do it. Pediatric radiology. 2016 May:46(6):748-63. doi: 10.1007/s00247-016-3614-y. Epub 2016 May 26 [PubMed PMID: 27229494]

Runge VM, Kirsch JE, Lee C. Contrast-enhanced MR angiography. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI. 1993 Jan-Feb:3(1):233-9 [PubMed PMID: 8428091]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKlisch J, Strecker R, Hennig J, Schumacher M. Time-resolved projection MRA: clinical application in intracranial vascular malformations. Neuroradiology. 2000 Feb:42(2):104-7 [PubMed PMID: 10663484]

Hennig J, Scheffler K, Laubenberger J, Strecker R. Time-resolved projection angiography after bolus injection of contrast agent. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 1997 Mar:37(3):341-5 [PubMed PMID: 9055222]

Behzadi AH, Zhao Y, Farooq Z, Prince MR. Immediate Allergic Reactions to Gadolinium-based Contrast Agents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Radiology. 2018 Feb:286(2):471-482. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017162740. Epub 2017 Aug 25 [PubMed PMID: 28846495]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDelfino JG, Krainak DM, Flesher SA, Miller DL. MRI-related FDA adverse event reports: A 10-yr review. Medical physics. 2019 Dec:46(12):5562-5571. doi: 10.1002/mp.13768. Epub 2019 Oct 8 [PubMed PMID: 31419320]