Introduction

The purpose of the nasolacrimal system is to drain tears from the ocular surface to the lacrimal sac and, ultimately, the nasal cavity. Blockage of the nasolacrimal system can cause tears to flow over the eyelid and down the cheek; this condition is epiphora.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

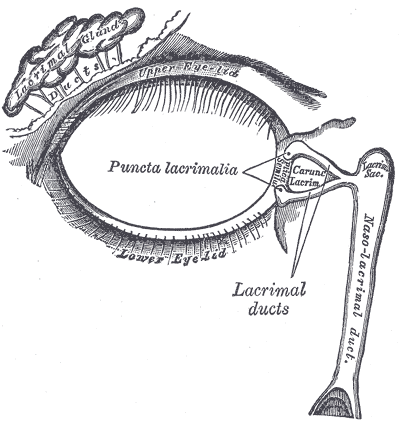

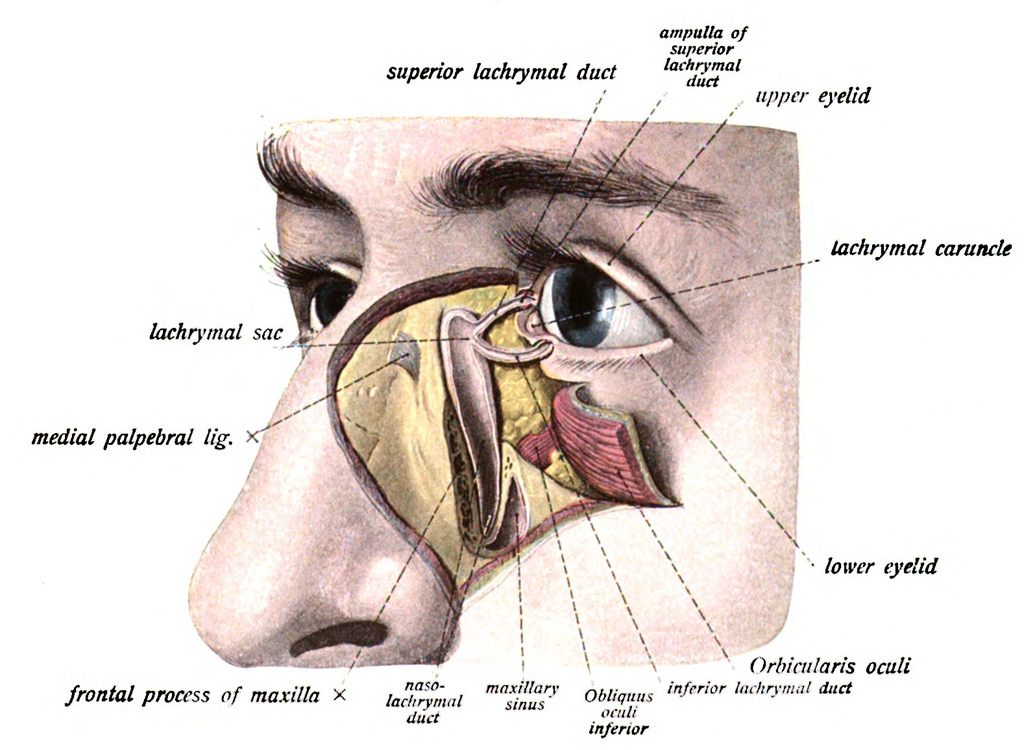

Both the upper eyelid and the lower eyelid have a small opening on the surface of the eyelid margin near the medial canthus. These are called puncta. Each puncta leads to a drainage canal that eventually flows into the lacrimal sac and then the nasal cavity. The drainage canal connecting the ocular surface to the nasal cavity consists of multiple parts.

Within the lower eyelid, the punctum leads to a 2 mm long ampulla, which runs perpendicular to the eyelid margin. The ampulla turns 90 degrees medially, becoming the inferior canaliculus and travels 8 to 10 mm before reaching the common canaliculus. The upper canaliculus travels 2 mm superiorly in the eyelid before turning 90 degrees medially and moving 8 to 10 mm before connecting to the common canaliculus. The common canaliculus drains into the lacrimal sac. Within the junction between the common canaliculus and the lacrimal sac is the valve of Rosenmuller. This apparatus is a one-way valve that prevents reflux from the lacrimal sac to the puncta.

The lacrimal sac drains inferiorly to the nasolacrimal duct, which is bordered medially by palatine bone and the inferior turbinate in the nose and laterally by maxillary bone. The nasolacrimal duct opens at the inferior meatus located underneath the inferior nasal turbinate. The lacrimal sac is approximately 10 to 15 mm in axial length and 13 to 20 mm in corneal length, and the nasolacrimal duct is 12 to 18 mm long. The inferior nasal meatus is partially covered by a mucosal fold known as the valve of Hasner.[1][2][3]

Embryology

The nasolacrimal duct starts forming around five weeks of gestation. It starts out as a linear thickening of ectoderm located in a groove between the nasal and maxillary prominences. This thickening eventually separates into a solid cord and sinks into the surrounding mesenchyme. Over time the cord canalizes forming the lacrimal sac and the beginning of the nasolacrimal duct. The nasolacrimal duct extends intranasally until it exits under the inferior turbinate. The lacrimal sac extends caudally to complete the canalicular system. The inside of the canal breaks down and forms a lumen so that the nasolacrimal system is patent. This process is generally complete by the time of birth.[4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Blood supply to the nasolacrimal area of the face is generally from the angular artery. The angular artery is considered a branch of the facial artery; however, some studies have shown that it can originate from the ophthalmic artery in some individuals. It terminates in anastomosis with the dorsal nasal branch of the ophthalmic artery. The angular artery and vein appear alongside the nose near the medial orbit. A correlating angular vein drains this region.

The medial and lateral portions of the eyelids have different lymphatic drainage systems. The medial one-third of the upper eyelid and the medial two-thirds of the lower eyelid drain to the submandibular lymph nodes. The lateral two-thirds of the upper eyelid and the lateral one-third of the lower eyelid drain to the pre-auricular lymph nodes.

Nerves

Cranial nerve VII supplies the motor innervation to the muscles of the face. The movement of these muscles aid in proper drainage of the tears through the nasolacrimal system by what is known as the lacrimal pump mechanism. Cranial nerve III and cranial nerve VII innervate the muscles that control the blinking of the eyelids. This action is the primary driver of the lacrimal pump mechanism.

Irritation of the ocular surface stimulates the ophthalmic branch of cranial nerve five, which begins the reflex tear arc pathway. The efferent pathway involves cranial nerve VII and parasympathetic fibers. The role of the sympathetic nervous system in tear production is not well understood.

Muscles

The action of the orbicularis muscle and surrounding tissues helps propel the flow of tears from the canaliculi to the nasolacrimal duct via the lacrimal pump mechanism.

Surgical Considerations

Eyelid Laceration with Canalicular Involvement

Lacrimal duct injuries can occur in patients of all ages. Lacerations most commonly affect the inferior canaliculus; however, laceration of both superior and inferior canaliculi may occur. Surgical repair of isolated canalicular laceration is recommended within 48 hours with anastomotic suture with or without canalicular intubation. [5] Dilate both upper punctum and lower punctum. If there is an un-involved punctum, probe it to the sac and irrigate to ensure there are no underlying blockages. Then identify the medial and lateral ends of the lacerated canaliculus. A silicone stent is an option if only one canaliculus is involved. If both are involved, silicone tubing or a Crawford stent are both viable choices. See below for stenting techniques for silicone and Crawford Stent. Suture skin as described in simple laceration repair.

Silicone Nasolacrimal Stent

Advance stent through punctum of lacerated canaliculus and out the distal end. Then insert the stent into the canaliculus opening of the lacerated lateral edge. Ensure the stent is seated in the punctum. Place 6-0 Vicryl sutures using a curved needle to anastomose the cut edges of the canaliculus and re-approximate the surrounding tissue. Leave these untied. Then place addition interrupted buried 5-0 vicryl sutures to reinforce the medial canthal tendon if needed. After placing all deep sutures, tie, and trim all sutures—close overlying skin with 6-0 plain gut suture.

Crawford Nasolacrimal Stent

Place the first end of the stent through punctum of lacerated canaliculus and out distal end. Then pass the same end through the previously identified proximal end and then advance through the lacrimal and nasal lacrimal duct. Retrieve the end of the stent from the nasal cavity. Pass the other end of the stent similarly through intact canaliculus. Place a cotton swab or similar product underneath the tubing loop between the upper and lower puncta. Pull the ends of the tubing taught through the nose and tie them together. Cut the excess tubing below the knot and then proceed to skin closure.[6][7][8][9]

Clinical Significance

One of the most common pathologies of the nasolacrimal duct is congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction, which occurs when the distal end of the nasolacrimal duct is not patent. Obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct is symptomatic in 5% of infants at birth, but most infants present with symptoms 4 to 6 weeks after birth; this is because the lacrimal gland does not fully develop until week 6, and therefore, infants younger than six weeks are not able to produce tears. Without tears, there is nothing for the nasolacrimal system to obstruct.

There are a variety of causes of acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction that can occur later in life. Depending on the level of obstruction in the nasolacrimal system, different symptoms are produced. Sometimes, obstructing the nasolacrimal system is the desired effect. For example, punctal plugs are a common therapy for patients suffering from dry eye symptoms.[10]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Tamboli DA, Harris MA, Hogg JP, Realini T, Sivak-Callcott JA. Computed tomography dimensions of the lacrimal gland in normal Caucasian orbits. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2011 Nov-Dec:27(6):453-6. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e31821e9f5d. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21659915]

Matsumoto H, Matsumoto A. An Unusual Case of Nasolacrimal Obstruction Caused by Foodstuffs. Case reports in ophthalmology. 2015 Sep-Dec:6(3):307-10. doi: 10.1159/000439425. Epub 2015 Sep 4 [PubMed PMID: 26483673]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYazici A, Bulbul E, Yazici H, Sari E, Tiskaoglu N, Yanik B, Ermis S. Lacrimal Gland Volume Changes in Unilateral Primary Acquired Nasolacrimal Obstruction. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2015 Jul:56(8):4425-9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-16873. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26193918]

Bewes T, Sacks R, Sacks PL, Chin D, Mrad N, Wilcsek G, Tumuluri K, Harvey R. Incidence of neoplasia in patients with unilateral epiphora. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2015 Jul:129 Suppl 3():S53-7 [PubMed PMID: 26173845]

Ducasse A, Arndt C, Brugniart C, Larre I. [Lacrimal traumatology]. Journal francais d'ophtalmologie. 2016 Feb:39(2):213-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2015.10.002. Epub 2016 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 26847220]

Sharma HR, Sharma AK, Sharma R. Modified External Dacryocystorhinostomy in Primary Acquired Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2015 Oct:9(10):NC01-5. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/15940.6624. Epub 2015 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 26557549]

Wang W, Zhan X, Qiang H, Cheng Z. [Efficacy of endoscopic nasal lateral wall dissection approach in the treatment of maxillary sinus diseases]. Lin chuang er bi yan hou tou jing wai ke za zhi = Journal of clinical otorhinolaryngology, head, and neck surgery. 2015 Jun:29(12):1075-7 [PubMed PMID: 26513994]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBalaji SM. Management of nasolacrimal duct injuries in mid-facial advancement. Annals of maxillofacial surgery. 2015 Jan-Jun:5(1):93-5. doi: 10.4103/2231-0746.161092. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26389043]

Yildirim Y, Kar T, Ayata A, Topal T, Çeşmeci E. Endoscopic endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy with ostial stent intubation following nasolacrimal duct stent incarceration. Current eye research. 2015:40(12):1292-3. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2015.1038358. Epub 2015 Sep 14 [PubMed PMID: 26367815]

Transection of Nasolacrimal Duct in Endoscopic Medial Maxillectomy: Implication on Epiphora., Imre A,Imre SS,Pinar E,Ozkul Y,Songu M,Ece AA,Aladag I,, The Journal of craniofacial surgery, 2015 Oct [PubMed PMID: 26468843]