Introduction

Basic airway management in children and adults includes assessing and managing airway patency, oxygen delivery, and ventilation. All efforts should be taken to maintain airway patency noninvasively unless indications for invasive airway management are apparent.

The following methods may accomplish noninvasive airway supplementation:

- Passive oxygenation by nasal cannula or nonrebreather mask

- Bag-valve-mask (BVM) ventilation

- Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, as in BVM with a positive-pressure valve, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), and bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP)

- Supraglottic airways, including the King Tube and laryngeal mask airway

Meanwhile, invasive airway management involves establishing a secure airway and placing patients on a mechanical ventilator via the following methods:

- Nasotracheal (NT) or endotracheal (ET) intubation

- Needle jet ventilation

- Cricothyroidotomy

- Tracheostomy

Needle jet ventilation may be used in pediatric patients younger than 8 years. Cricothyroidotomy is appropriate for adults and children older than 8 years.[1][2]

Proper airway management begins by determining the best airway approach for the patient. Factors that can influence airway choice include obesity, macroglossia, evidence of trauma, cervical collar use, presence of a gag reflex, and age.

After selecting the airway type, the patient's head is positioned for airway placement. Methods for head positioning include the following:

- Head tilt-chin lift maneuver. One hand tilts the forehead while the other lifts the chin. Both actions extend the neck, reduce upper airway obstruction, and align the upper respiratory airways. This maneuver puts the patient in a sniffing position, with the nose pointed upward and forward.

- Chin lift: Both hands are placed underneath the mandible and chin. The mandible is then lifted until the teeth barely touch.

- Jaw-thrust maneuver: The spine is maintained in a neutral position. Then, the sides of the mandibular angle are lifted forward to lift the jaw and open the airway. This method is appropriate for individuals with a possible cervical spinal cord injury.

Differences exist between the pediatric and adult airways. For example, prepubescent pediatric patients have a large occiput that can hyperflex the neck and obstruct the trachea. The head tilt-chin lift maneuver can correct this problem. However, care must be taken using this maneuver in children who have a weak trachea because neck overextension can also obstruct the airway.

The head tilt-chin lift may be inadequate to keep the airway patent in children with a large, floppy tongue. The jaw-thrust maneuver is an alternative for these patients.

Once properly positioned, effective breaths must be delivered mouth-to-mouth or via BVM ventilation. If difficulties are encountered in delivering breaths, airway adjuncts like an oral pharyngeal airway (OPA) device or nasopharyngeal airway (NPA) may be used to keep the airway patent (see Image. Airway Adjuncts). OPAs are appropriate for unresponsive patients. NPA devices may be used on both unconscious and awake patients. Thus, NPAs are beneficial if intubation is not indicated or needs to be delayed. NPA use may also be a temporizing measure if awake intubation is necessary.

NPAs are hollow plastic or soft rubber tubes inserted into the nose and posterior pharynx. These devices should not cause patients to gag. Thus, NPAs are the best airway adjuncts for awake patients. These devices are also indicated for semiconscious patients with an intact gag reflex and may not tolerate an OPA. NPAs may also be useful when a patient's mouth is difficult to open, as in cases of angioedema and trismus. However, despite their many applications, NPAs only keep the airway patent in stable patients with spontaneous respirations or serve as a temporizing measure for patients needing an ET or NT airway.

NT intubation was traditionally a commonly performed airway management method among critical care and emergency physicians. However, most clinicians today prefer the ET intubation route, which has demonstrated better results and fewer complications than the NT method. Oral and maxillofacial surgery are the only disciplines where NT intubation is widely used. Studies have since found that using an NPA before NT intubation during surgery improves the ease of NT tube insertion and minimizes bleeding during NT tube placement.[3][4]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

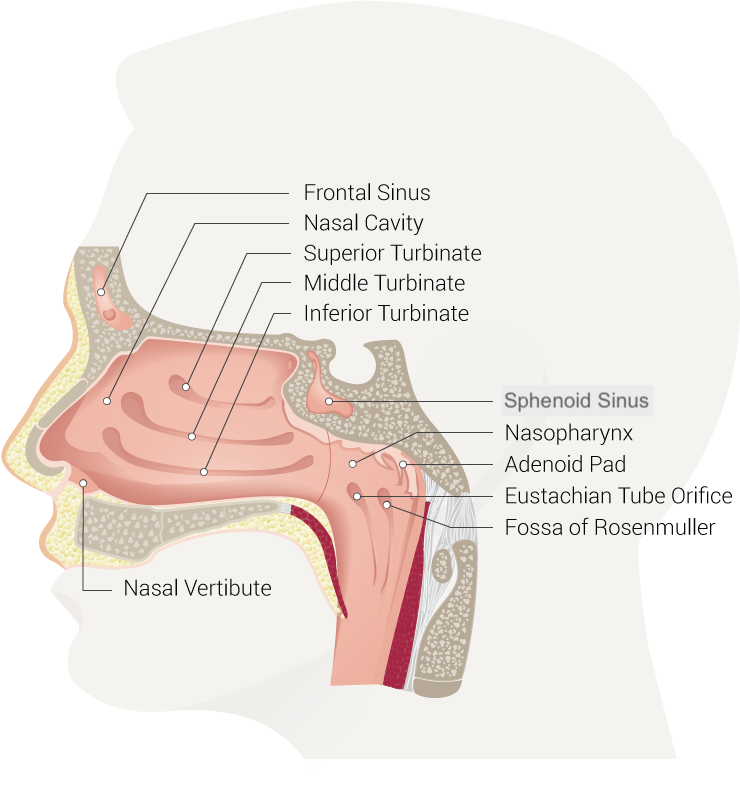

The nose communicates with the following structures (see Image. Nasal Cavity):

- Facial sinuses

- Brain via the cribriform plate

- Pharynx

- Esophagus

- Trachea via the nasopharynx

The nose is separated into 2 nares by a mostly cartilaginous nasal septum. Each naris is comprised of 2 pathways: lower and upper. The lower pathway lies along the nasal floor underneath the inferior turbinate. The upper pathway lies above the inferior turbinate and below the middle turbinate. The middle turbinate is a vascular structure connected with the cribriform plate. NPA placement or NT intubation in this region risks vascular damage. Thus, the lower pathway is better for airway device insertion than its upper counterpart.

The nasopharynx is continuous with the oropharynx, which connects to the hypopharynx posterioinferiorly. The hypopharynx is posterior to the larynx and superior to the entry point into the trachea and esophagus. A view into the larynx from superior to inferior should reveal the vallecula, epiglottis, vocal folds, and vocal cords. The vocal cords open into the trachea.

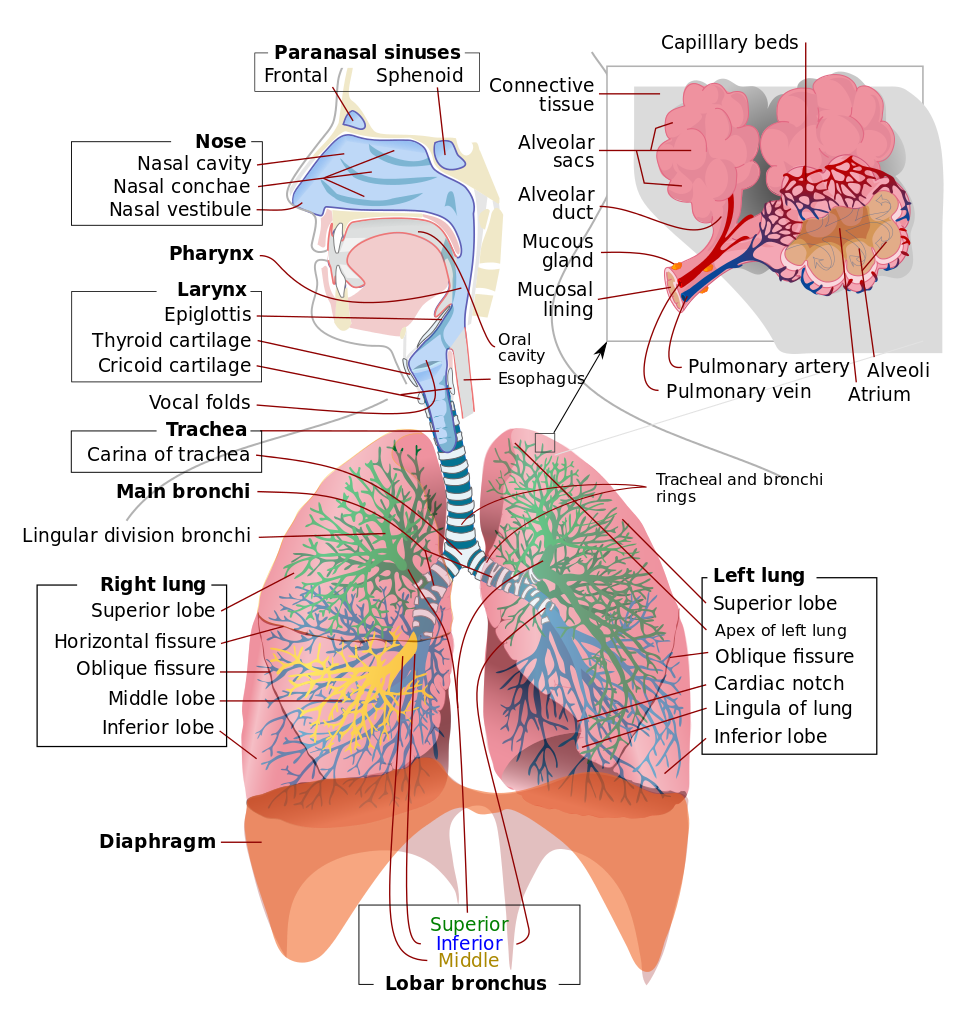

The NPA or NT tube must be directed posteriorly toward the occiput and nasopharynx along the nasal floor and then caudally in the lungs' direction (see Image. Respiratory System).

Indications

The nasal route is often the first and, sometimes, only option for stabilizing the airway. In emergency and critical care settings, NP or NT tube placement is indicated in patients with the following:

- Strong gag reflex

- Limited mouth opening

- Macroglossia

- Cervical spine instability

- Severe cervical kyphosis

- Severe arthritis

- Intraoral masses

- Structural abnormalities

- Trismus

- Angioedema

Additionally, NT intubation should be considered preoperatively in patients requiring maxillofacial surgery or dental procedures.[5][6] NT intubation is also better tolerated than the ET method in awake patients and should be considered when awake intubation is required.

NT tube placement is advantageous in difficult airways and persistently low oxygen saturation despite optimal preoxygenation. These challenges are often present in patients with congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and asthma exacerbation. Individuals with these conditions must be allowed to maintain their respiratory drive while the airway is secured. Sedation and paralysis can make airway management even more challenging in these individuals. Additionally, orthopnea can occur in these patients. NT intubation may be performed when the patient is awake and in a sitting position.[7]

NT intubation is the most common airway management method during oral and maxillofacial surgery. This airway type enables adequate visualization of the oral cavity during the procedure. As mentioned earlier, NPA insertion makes subsequent NT tube placement easier and lessens complications such as bleeding during NT intubation.

Contraindications

Relative contraindications for NPA placement include suspected epiglottitis, large nasal polyps, recent nasal surgery, coagulopathy, and anticoagulant intake. Abnormal hemostasis predisposes to nasal hemorrhage.

Absolute contraindications for NPA and NT intubation include basilar skull fractures, facial trauma, and disruption of the midface, nasopharynx, or roof of the mouth.

Equipment

The following must be available during NPA placement:

- NPA devices of different sizes

- Lidocaine jelly

- Topical vasoconstrictor nasal spray, such as oxymetazoline 0.05% and phenylephrine 0.5%

- Aerosolized 2% to 4% lidocaine

- Suction tubing

- Suction yanker

- BVM

- Nasal cannula for apneic oxygenation if patient sedation is considered

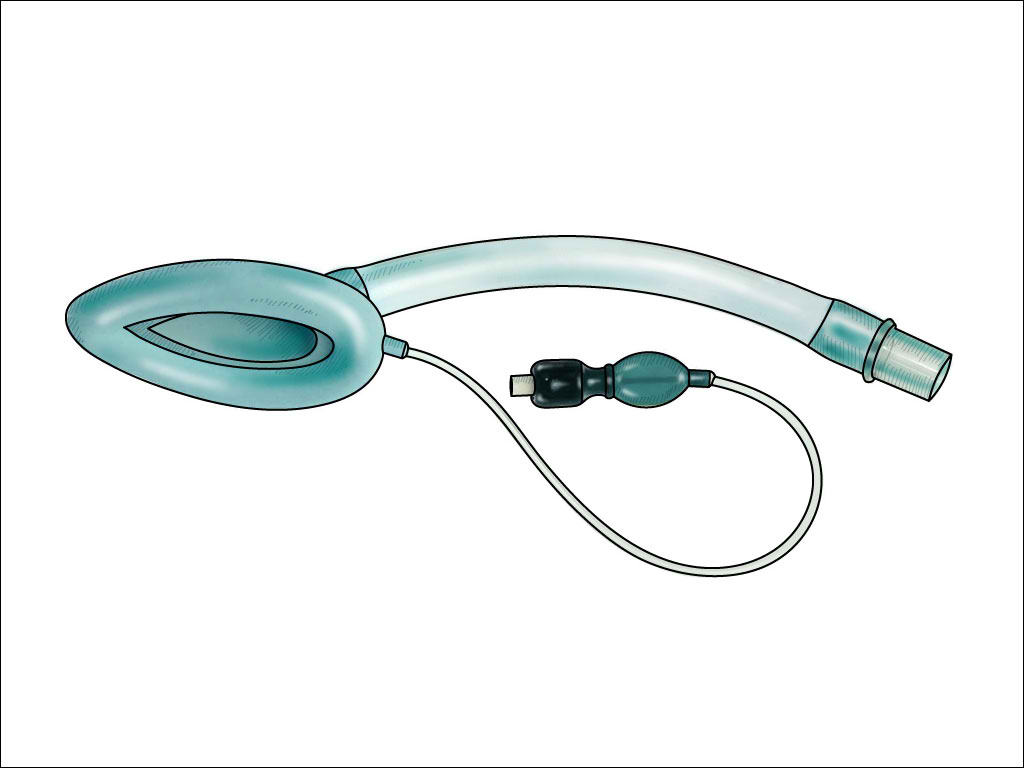

- Alternative airway management equipment, such as a laryngeal mask airway (see Image. Laryngeal Mask Airway), glideslope, bougie, and surgical airway tools

NPA size selection ensures optimal airway patency and minimizes complications. Adult NPA sizes range from 6 to 9 cm. Sizes 6 to 7 cm should be considered in adults with a small physique. A 7- to 8-cm NPA is appropriate for adults with a medium build. An 8- to 9-cm NPA is suitable for adults with a large build.[8] The ear lobe or tragus technique can also help estimate adult NPA size. The NPA is positioned with the beveled tip pointing toward either ear lobe and the other end on the nasal tip. The correct-sized NPA will just reach the ear lobe.[9]

The mandible technique is another alternative method for estimating NPA size in adults. The NPA is placed at the nasal opening and oriented toward the mandibular angle. The device is too long if it goes past the mandible and too short if it does not reach the mandible.

On the other hand, estimating pediatric NPA sizes is not as straightforward as in adults. The recommended sizes are summarized in the following table:

Table. Recommended NPA Sizes for Pediatric Patients

| Age | NPA Size |

| Preterm to 1 month | 3 |

| 1-6 months | 3.5 |

| 6-18 months | 4 |

| 18 months-3 years | 4.5 |

| 3-6 years | 5 |

| 6-9 years | 5.5 |

| 9-12 years | 6 |

Generally, the NPA size is around the same size as an ET tube or 0.5 mm larger.[10] NPA size selection is generally based on the length, not the internal diameter, so the device's tip sits just above the epiglottis. Studies found that patient height was a better predictor of proper NPA size than the nares-to-earlobe and nares-to-mandible techniques.[11] Some experts propose that if NPAs of different lengths exist for a particular diameter—like what some manufacturers produce—the longest one should be used, preferably with an adjustable flange.[12]

Pediatric NPA sizing may also be accomplished using a Broselow tape, a color-coded tape measure that classifies a child into 1 of 8 color zones by height (see Image. Broselow Tape Measurement). The Broselow tape also contains additional guides about size selection for other airway equipment types and medications used during resuscitation.[13]

Personnel

Airway stabilization is part of the training of healthcare professionals, as they have a deep understanding of head, neck, and pulmonary anatomy and physiology. Ideally, NPA placement must be performed by adequately trained personnel, which includes professionals practicing in the following disciplines:

- Medicine

- Nursing

- Respiratory therapy

Prehospital providers may also perform airway stabilization under the supervision of a highly trained healthcare professional. In some territories, prehospital providers may stabilize the airway independently as long as the method used is within the scope of their training. Most emergency medical services personnel are sufficiently trained in NPA placement.

NT intubation is rarely performed in the emergency department. However, if the procedure is warranted, emergency physicians unfamiliar with the technique may refer the patient to the on-duty anesthesiologist or otorhinolaryngologist to perform this procedure.

Nurses and respiratory therapists are more than adequately trained to insert an NPA. Additionally, they can assist in monitoring the patient's respiratory status and ensuring that the airway device is secure and oxygenation is adequate.

Preparation

Preparing to insert an NPA ideally involves 2 steps. The first is obtaining the correct size NPA. The second is coating the airway device with water-soluble lubricant or anesthetic jelly. However, during emergencies or when resources are scarce, the provider may be unable to prepare adequately and be forced to insert the NPA or NT tube blindly.

Other preparatory steps include the following, not necessarily in the below order:

- Attaching the pulse oximeter and blood pressure and cardiac monitors

- Positioning the patient in the sniffing position

- Setting up an end-tidal carbon dioxide monitor (capnography)

- Placing peripheral intravenous access sites bilaterally

- Starting 1 liter of intravenous crystalloid fluid if the patient is not congested or at risk of fluid overload

- Preoxygenation via nasal cannula, nonrebreather, BVM, or BiPAP to increase the patient's oxygen reserve and time to desaturation after sedation or neuromuscular blocker administration

- Ensuring that the face mask forms a tight seal around the mouth and nose during preoxygenation

- Having a BVM ready at the bedside

- Turning on the wall suction and setting up the suction tubing and yanker

- Having a respiratory therapist prepare a ventilator

- Preparing sedatives and neuromuscular blockers if required

- Preparing a backup airway

- Having ET and NT tubes of different sizes on standby

- Checking the tube cuff for air leaks

- Spraying a topical vasoconstrictor in the bilateral nares to reduce bleeding risk

- Coating an NPA with lidocaine jelly or ointment to anesthetize and lubricate the airway

- Placing the correct NPA into a patent and horizontal naris

Once a secure airway has been established, the NPA should be removed immediately to minimize complications.

Technique or Treatment

The NPA must be inserted into the most patent and horizontal nares with the concave side facing down to facilitate insertion into the posterior pharynx. The NPA may be rotated if resistance is present to allow the tube to fit snugly into the nares. Direct the tube in the occiput's direction posteriorly and along the nasal floor. This prevents cephalad positioning and ensures the NPA passes through the lower pathway of the naris.

The oral cavity must be examined after NPA insertion. The tube is too large if you see it protruding lower than the uvula. Once the NPA is inserted, a more secure airway, like an ET or NT tube, may be placed if required.[14]

Complications

The potential complications of NPA placement and NT intubation include the following:

- Epistaxis due to nasal mucosal injury

- Turbinate fracture

- Turbinectomy

- Intracranial placement through a basilar skull fracture

- Retropharyngeal dissection or laceration

- Sinusitis, which can result in sepsis in the immunocompromised

- Gastric distension if the NPA is too large or the NT tube is inserted in the esophagus

Blind NT intubation increases the risk of esophageal placement and retropharyngeal laceration, but otherwise, blind and bronchoscopic placement have similar complications.[15]

NPA placement is absolutely contraindicated when the patient has a basilar skull fracture. This condition risks cephalad NPA insertion and possible damage to brain structures.

Gastric distension arising from inappropriate airway placement may cause vomiting, increasing the risk of aspiration pneumonia. This condition can further reduce the lungs' oxygenation and ventilation.

An upper airway obstruction may result from long-term NPA placement. Interestingly, prolonged NPA use may be associated with good interdisciplinary communication between emergency medical services, the emergency department, and other admitting services like the intensive care unit or otorhinolaryngology services. A well-placed NPA can stay in place for up to 20 months, though it may elicit a foreign-body reaction.[16][17]

Every procedure carries a complication risk. However, good patient selection and proper technique can help avoid adverse events when managing the airway.

Clinical Significance

NPAs keep the airway patent in spontaneously breathing patients with an intact gag reflex. NPA insertion is most useful for individuals experiencing cardiorespiratory distress, undergoing oral or maxillofacial surgery, and possessing a difficult airway. Additionally, these devices provide a clear path for ET or NT intubation if a more secure airway is required.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Airway management using an NPA requires an interprofessional team approach in various clinical settings. The team may include the following members:

- Emergency medical services personnel: often the first responders in emergencies where maintaining a patent airway is crucial. These providers may initiate the use of NPAs in the prehospital setting.

- Emergency medicine physicians, anesthesiologists, and intensivists: involved in the decision-making process for NPA use and inserting the device.

- Nurses: may be involved in inserting, monitoring, and maintaining NPAs.

- Respiratory therapists: essential in airway management, particularly when mechanical ventilation is required. These professionals may assist in inserting and monitoring NPAs and provide expertise in respiratory care.

- Speech-language pathologists: may be involved in cases where patients have swallowing difficulties or speech-related concerns related to using airway devices.

Effective communication and collaboration among these team members are crucial to successful airway management.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Respiratory System. This illustration shows the upper respiratory tract, consisting of the paranasal sinuses, nose, nasal cavity, nasal conchae, nasal vestibule, pharynx, larynx, epiglottis, and vocal folds. Of the paranasal sinuses, the frontal and sphenoid sinuses are included. The illustration also shows the lower respiratory region, comprised of the thyroid cartilage, cricoid cartilage, trachea and tracheal carina, main bronchi, tracheal and bronchial rings, lobar bronchi (superior, middle, and inferior), and right and left lungs. The insert shows alveolar anatomy, which includes the alveolar sacs, alveolar duct, mucous gland, mucosal lining, pulmonary artery and vein, capillary beds, and alveolar atrium.

Contributed by Wikimedia Commons, LadyofHats (Public Domain)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Okuno K, Ono Minagi H, Ikai K, Matsumura Ai E, Takai E, Fukatsu H, Uchida Y, Sakai T. The efficacy of nasal airway stent (Nastent) on obstructive sleep apnoea and prediction of treatment outcomes. Journal of oral rehabilitation. 2019 Jan:46(1):51-57. doi: 10.1111/joor.12725. Epub 2018 Oct 21 [PubMed PMID: 30281824]

Dubey M, Pathak S, Ahmed F. Topicalisation of airway for awake fibre-optic intubation: Walking on thin ice. Indian journal of anaesthesia. 2018 Aug:62(8):625-627. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_63_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30166659]

Folino TB, Mckean G, Parks LJ. Nasotracheal Intubation. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763142]

Dhakate VR, Singam AP, Bharadwaj HS. Evaluation of Nasopharyngeal Airway to Facilitate Nasotracheal Intubation. Annals of maxillofacial surgery. 2020 Jan-Jun:10(1):57-60. doi: 10.4103/ams.ams_190_19. Epub 2020 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 32855916]

Spector ME, Pepper JP, Sullivan S, Marentette L, McKean E. Nasopharyngeal airway to prevent tension pneumocephalus after open resection of anterior skull base tumors. Ear, nose, & throat journal. 2016 Dec:95(12):E32-E35 [PubMed PMID: 27929605]

Kurnutala LN, Sandhu G, Bergese SD. Fiberoptic nasopharyngoscopy for evaluating a potentially difficult airway in a patient with elevated intracranial pressure. Journal of clinical anesthesia. 2016 Nov:34():336-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.05.023. Epub 2016 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 27687404]

Takasugi Y, Futagawa K, Konishi T, Morimoto D, Okuda T. Possible association between successful intubation via the right nostril and anatomical variations of the nasopharynx during nasotracheal intubation: a multiplanar imaging study. Journal of anesthesia. 2016 Dec:30(6):987-993. doi: 10.1007/s00540-016-2253-7. Epub 2016 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 27678497]

Roberts K, Whalley H, Bleetman A. The nasopharyngeal airway: dispelling myths and establishing the facts. Emergency medicine journal : EMJ. 2005 Jun:22(6):394-6 [PubMed PMID: 15911941]

Briggs B, Countryman C, McGinnis HD. One Notable Complication of Nasopharyngeal Airway: A Case Report. Clinical practice and cases in emergency medicine. 2020 Nov:4(4):584-586. doi: 10.5811/cpcem.2020.8.48811. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33217278]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSwaika S, Ghosh S, Bhattacharyya C. Airway devices in paediatric anaesthesia. Indian journal of anaesthesia. 2019 Sep:63(9):721-728. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_550_19. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31571685]

Stoneham MD. The nasopharyngeal airway. Assessment of position by fibreoptic laryngoscopy. Anaesthesia. 1993 Jul:48(7):575-80 [PubMed PMID: 8346770]

Thangavel AR, Panneerselvam S, Rudingwa P, Sivakumar RK. Nasopharyngeal airway size selection and its implication in the management of pediatric difficult airway. Journal of anaesthesiology, clinical pharmacology. 2020 Oct-Dec:36(4):565-566. doi: 10.4103/joacp.JOACP_187_19. Epub 2021 Jan 18 [PubMed PMID: 33840946]

Borkar N, Sharma C, Francis J, Kumar M, Singha SK, Shukla A. Applicability of the Broselow Pediatric Emergency Tape to Predict the Size of Endotracheal Tube and Laryngeal Mask Airway in Pediatric Patients Undergoing Surgery: A Retrospective Analysis. Cureus. 2023 Jan:15(1):e33327. doi: 10.7759/cureus.33327. Epub 2023 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 36741616]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAlvarado AC, Panakos P. Endotracheal Tube Intubation Techniques. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32809565]

Ellis DY, Lambert C, Shirley P. Intracranial placement of nasopharyngeal airways: is it all that rare? Emergency medicine journal : EMJ. 2006 Aug:23(8):661 [PubMed PMID: 16858116]

Zwank M. Middle turbinectomy as a complication of nasopharyngeal airway placement. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2009 May:27(4):513.e3-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.09.038. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19555632]

Kim BJ, Shoffel-Havakuk H, Johns MM 3rd. Retained Nasal Trumpet for 20 Months: An Unusual Foreign Body. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery. 2019 Jan 1:145(1):93-94. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.2939. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30452513]