Introduction

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is a life-threatening illness almost exclusively affecting neonates. NEC has a mortality rate as high as 50%. The pathophysiolgy of NEC is inflammation of the intestine leading to bacterial invasion causing cellular damage and death which causes necrosis of the colon and intestine. As NEC progresses, it can lead to intestinal perforation causing peritonitis, sepsis, and death. The signs and symptoms of NEC, poor feeding, vomiting, lethargy, abdominal tenderness, are nonspecific, so clinicians must remain suspicious when presented with these signs and symptoms in the neonatal population. [1][2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Necrotizing enterocolitis is caused by bacterial invasion into the intestinal wall. This leads to inflammation and cellular destruction of the wall of the intestine. If unrecognized and untreated, an intestinal perforation may occur, causing spillage of intestinal contents into the peritoneum and resulting in peritonitis. The specific mechanism and cause of this bacterial invasion are not yet understood. In premature neonates, gastrointestinal tract immaturity is believed to play a role in the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis.

Epidemiology

Necrotizing enterocolitis is a disease affecting neonates and is the most common life-threatening emergency affecting the gastrointestinal tract of infants in the neonatal intensive care unit. Necrotizing enterocolitis typically occurs in the second to third week of life. Several risk factors have been identified, but prematurity, low birth weight, and formula feeding have been identified as primary risks[2]. Specifically, high osmotic strength formula feeding has been implicated as a risk factor. Genetic factors may also play a role[1]. Incidence worldwide varies between 0.3 to 2.4 infants per 1000 live births. Nearly 70% of these cases occur in premature infants born before 36 weeks gestation. Necrotizing enterocolitis affects 2% to 5% of all premature infants and is responsible for nearly 8% of all NICU admissions. Overall, mortality ranges from 10% to 50%. However, in the most severe cases, involving perforation, peritonitis, and sepsis, mortality approaches 100%.

While necrotizing enterocolitis primarily occurs in premature infants, it has been documented in full-term infants. In this population, onset is typically in the first few days of life and is usually associated with a hypoxic event, such as a cyanotic congenital heart defect.

Histopathology

The tissue of the intestinal wall in patients with necrotizing enterocolitis shows inflammation and bacterial invasion. As the disease progresses, tissue shows ischemia, followed by necrosis[3], and ultimately perforation, which may be either microperforation or a frank perforation. Microperforation leads to pneumatosis intestinalis, or air within the wall of the intestine. In the event of perforation, the peritoneal cavity becomes contaminated with bacteria and bowel content, leading to peritonitis.

History and Physical

The signs and symptoms of necrotizing enterocolitis are highly variable, nonspecific and subtle[4]. Parents often report decreased activity and fatigue. They may also report gastrointestinal symptoms such as decreased appetite, vomiting, diarrhea, and increasing abdominal girth. Patients may also experience blood in the stool. As the disease progresses, the patient may experience systemic signs related to respiratory failure and circulatory collapse, such as cyanosis and unresponsiveness.

Physical examination findings may include abdominal distention, abdominal tenderness to palpation, visible intestinal loops, decreased bowel sounds, palpable abdominal mass, and erythema of the abdominal wall. Systemic findings may include respiratory failure, circulatory collapse, and decreased peripheral perfusion.

Evaluation

The single most important test required to make the diagnosis is an abdominal plain film series including anterior-posterior and left lateral decubitus views. Findings of dilated loops of bowel, pneumatosis intestinalis, and portal venous air is diagnostic for necrotizing enterocolitis. Pneumatosis intestinalis is the visualization of small amounts of air within the bowel wall and is pathognomonic for necrotizing enterocolitis. Portal venous air is not universally present but is a poor prognostic sign when found. Free air in the abdomen may be seen when perforation has occurred.

An abdominal radiograph is a valuable tool for tracking the progression of the disease as well. In most cases, this should be repeated serially every 6 hours until definitive treatment has occurred.

Laboratory studies have limited utility and are non-specific. Leukopenia with a white blood cell count below 1500 per microliter is a strong indicator of established sepsis. A comprehensive metabolic panel may show hyponatremia and low serum bicarbonate. Blood cultures are usually negative. A breath hydrogen test may be positive but is rarely performed.

Treatment / Management

Treatment begins with standard resuscitation based on the patient's vital signs. Airway, breathing and circulation must be supported in a patient in extremis. Fluid resuscitation is indicated for hypotension. In the event of respiratory failure, the patient may need endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. Pediatric Advanced Life Support guidelines should be followed for resuscitation in circulatory collapse.

The first intervention when necrotizing enterocolitis is suspected is to stop all enteral feedings and maintain the patient NPO. A nasogastric tube should be placed for decompression of the dilated bowels. Intravenous antibiotics should be started, with broad-spectrum coverage. The suggested antibiotic regimen includes ampicillin, gentamicin, and either clindamycin or metronidazole. While the patient is NPO, total parenteral nutrition must be provided. If this conservative therapy is effective, infants may resume enteral feedings once signs of infection have resolved. This may take several days to a week in some cases. The presence of normal bowel movements determines the return of bowel function.

In infants who have worsening condition or bowel perforation or who do not respond to medical therapy, surgical intervention is indicated. Laparotomy is the standard approach, and surgery is as conservative as possible, with removal only of portions of unquestionably necrotic or perforated intestine in an attempt to preserve as much intestine as possible[5]. Particular effort is made to preserve the ileocecal valve. A diverting ostomy may be placed and is typically utilized in the infant in shock or extremis or has significant peritonitis. Following recovery, the stoma may be reversed. Primary anastomosis is generally contraindicated due to the risk of ischemia at the anastomosis[6].

Laparotomy may be contraindicated in patients who are extremely small and ill, as they may not be stable enough to tolerate the surgery[7]. In these patients, if perforation and free air occur, an alternative treatment of insertion of a peritoneal drain may be considered. This can be performed under local anesthesia in the nursery. (B3)

Future treatments are currently being studied, including probiotics[8][9][10][11][12], agents which block the production of nitrous oxide, and even low-dose carbon monoxide.(A1)

Differential Diagnosis

With the potentially vague presentation of necrotizing enterocolitis, the differential diagnosis is broad. The symptoms of necrotizing enterocolitis in this population, including nausea and vomiting, may be the result of congenital abnormalities, such as pyloric stenosis, duodenal atresia, tracheoesophageal fistula, gastroschisis, or malrotation with or without midgut volvulus. Infectious causes include gastroenteritis, urinary tract infection, sepsis, meningitis, and pneumonia. Other possibilities include intussusception or testicular torsion. Clinicians also must always consider child abuse, including intracranial injury.

Prognosis

The prognosis for necrotizing enterocolitis depends on the severity of the condition at the time it is recognized and treatment is started. The overall mortality ranges from 10% to 50%. However, for infants with advanced necrotizing enterocolitis, including the full-thickness destruction of the intestinal wall which leads to perforation and peritonitis, mortality approaches 100%.

Complications

Complications may arise from prolonged hospitalization and treatment. Patients may require prolonged total parenteral nutrition, which may lead to liver failure. Postoperative adhesions and scarring may lead to stricture and obstruction. Other complications include short bowel syndrome, intestinal failure, nutritional deficiencies, and associated defects in growth and development.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Following surgery for necrotizing enterocolitis, infants should receive intravenous antibiotics and total parenteral nutrition for at least 2 weeks. Routine medical care, including monitoring for and correcting electrolyte abnormalities or anemia, should also continue during that time. Ventilatory support should be provided if needed.

Consultations

Any patient presenting with necrotizing enterocolitis will require a surgical consult. Often, the infant will be admitted to the NICU, requiring a neonatal intensivist consult as well.

Deterrence and Patient Education

In very low birthweight infants, breastfed infants have a lower incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis. Mothers of these infants should be counseled on the benefits of breastfeeding, particularly regarding its relationship to the development of necrotizing enterocolitis.

Antenatal and postnatal conditions which cause diminished intestinal blood flow have been implicated in the increased risk for development of necrotizing enterocolitis. For example, conditions causing placental insufficiency in the antenatal period, such as hypertension, preeclampsia, and cocaine use, may decrease infant intestinal blood flow. For infants born under these conditions, cautious enteral feeding is justified. Postnatal conditions causing similar decreased splanchnic blood flow and therefore an increased risk of necrotizing enterocolitis, include patent ductus arteriosus, other cardiac diseases, or general hypotension and cardiovascular compromise.

Pearls and Other Issues

Necrotizing enterocolitis is potentially fatal and may present with vague signs and symptoms. Early recognition is paramount. The mainstay of treatment involves cessation of enteral feedings, gastric decompression with a nasogastric tube, intravenous antibiotics, and total parenteral nutrition. The most important diagnostic study is the abdominal plain film, which will show dilated loops of bowel and may show portal venous air or pneumatosis intestinalis, which is pathognomonic. Early surgical consultation is necessary, and many of these patients require NICU admission.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of necrotizing enterocolitis requires an interprofessional team approach. Diagnosis may be challenging given the vague and variable symptoms. The initial evaluation is often by an emergency department physician. Radiologists play a critical role in determining the presence of pneumatosis intestinalis, which is pathognomonic for NEC. Once the diagnosis is made, the initiation of treatment requires involvement of a large team of professionals. Nurses play a vital role in establishing vascular access for antibiotics, fluid resuscitation, and lab analysis. Early surgical consult is paramount.

These infants are typically admitted to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, with a consult to a neonatal intensivist. Again, nursing staff plays a key role in frequent assessment, as the patient's condition may change quickly. Pharmacists will be involved in the antibiotic selection and dosing for these patients. A nutritionist must be involved for the initiation of total parenteral nutrition. An interprofessional team approach is vital to improve the outcomes for patients suffering from necrotizing enterocolitis.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

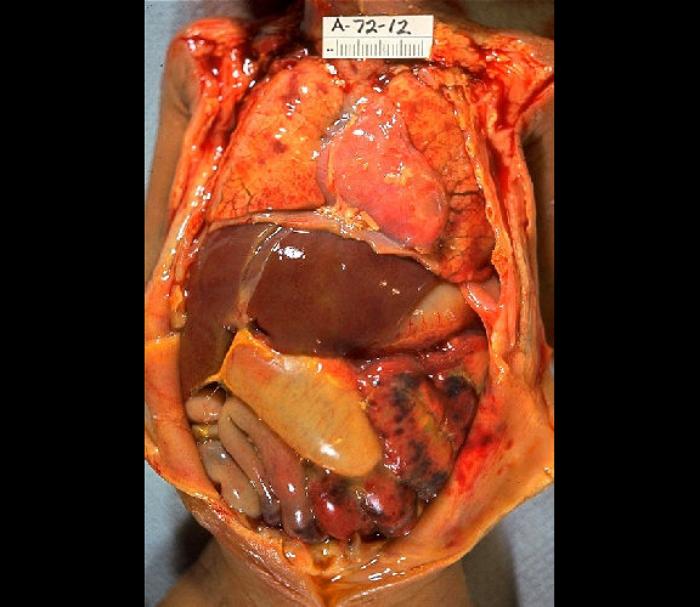

Gross Pathology of Neonatal Necrotizing Enterocolitis. Autopsy of an infant with abdominal distention, necrosis, hemorrhage, and peritonitis due to perforation.

Edwin P Ewing Jr, MD/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Cuna A, George L, Sampath V. Genetic predisposition to necrotizing enterocolitis in premature infants: Current knowledge, challenges, and future directions. Seminars in fetal & neonatal medicine. 2018 Dec:23(6):387-393. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2018.08.006. Epub 2018 Aug 18 [PubMed PMID: 30292709]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAfzal B, Elberson V, McLaughlin C, Kumar VH. Early onset necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) in premature twins. Journal of neonatal-perinatal medicine. 2017:10(1):109-112. doi: 10.3233/NPM-1616. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28304317]

Rugolotto S, Gruber M, Solano PD, Chini L, Gobbo S, Pecori S. Necrotizing enterocolitis in a 850 gram infant receiving sorbitol-free sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate): clinical and histopathologic findings. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association. 2007 Apr:27(4):247-9 [PubMed PMID: 17377608]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGephart SM, Hanson C, Wetzel CM, Fleiner M, Umberger E, Martin L, Rao S, Agrawal A, Marin T, Kirmani K, Quinn M, Quinn J, Dudding KM, Clay T, Sauberan J, Eskenazi Y, Porter C, Msowoya AL, Wyles C, Avenado-Ruiz M, Vo S, Reber KM, Duchon J. NEC-zero recommendations from scoping review of evidence to prevent and foster timely recognition of necrotizing enterocolitis. Maternal health, neonatology and perinatology. 2017:3():23. doi: 10.1186/s40748-017-0062-0. Epub 2017 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 29270303]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAcute inflammatory surgical disease., Fagenholz PJ,de Moya MA,, The Surgical clinics of North America, 2014 Feb [PubMed PMID: 24267493]

Geng Q, Wang Y, Li L, Guo C. Early postoperative outcomes of surgery for intestinal perforation in NEC based on intestinal location of disease. Medicine. 2018 Sep:97(39):e12234. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012234. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30278493]

Craven DP, Fowler JS, Foster ME. Management of a neonate with necrotizing entero-colitis and eight prolapsed stomas in a dehisced wound. Journal of wound, ostomy, and continence nursing : official publication of The Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society. 1999 Jul:26(4):214-20 [PubMed PMID: 10476178]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWilkins T, Sequoia J. Probiotics for Gastrointestinal Conditions: A Summary of the Evidence. American family physician. 2017 Aug 1:96(3):170-178 [PubMed PMID: 28762696]

Bron PA, Kleerebezem M, Brummer RJ, Cani PD, Mercenier A, MacDonald TT, Garcia-Ródenas CL, Wells JM. Can probiotics modulate human disease by impacting intestinal barrier function? The British journal of nutrition. 2017 Jan:117(1):93-107. doi: 10.1017/S0007114516004037. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28102115]

Cruchet S, Furnes R, Maruy A, Hebel E, Palacios J, Medina F, Ramirez N, Orsi M, Rondon L, Sdepanian V, Xóchihua L, Ybarra M, Zablah RA. The use of probiotics in pediatric gastroenterology: a review of the literature and recommendations by Latin-American experts. Paediatric drugs. 2015 Jun:17(3):199-216. doi: 10.1007/s40272-015-0124-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25799959]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVersalovic J. The human microbiome and probiotics: implications for pediatrics. Annals of nutrition & metabolism. 2013:63 Suppl 2():42-52. doi: 10.1159/000354899. Epub 2013 Nov 8 [PubMed PMID: 24217035]

Dylag K, Hubalewska-Mazgaj M, Surmiak M, Szmyd J, Brzozowski T. Probiotics in the mechanism of protection against gut inflammation and therapy of gastrointestinal disorders. Current pharmaceutical design. 2014:20(7):1149-55 [PubMed PMID: 23755726]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence