Introduction

A digital nerve block is a simple procedure that provides immediate anesthesia for many injuries and procedures affecting the fingers and toes (ie, digits). These comprise fractures, dislocations, laceration repairs, nail removals, foreign body removals, mass excisions, and treating infections. A digital nerve block is one of the most commonly performed nerve blocks in the primary care setting and the emergency department due to its wide variety of uses and efficacy.[1] The digital nerve block has several advantages over a local anesthetic injection for digital injuries and treatment. They include rapid anesthetic effect, decreased risk of direct trauma to blood vessels and nerves (neurovascular bundles), a single injection is usually enough, and a lower volume of anesthetic solution is used. The latter is important as only a limited volume of anesthetic is tolerated in the restricted space of the digits.[2] A digital nerve block is also considered superior to intravenous and oral medications as it acts locally and, therefore, has a lower likelihood of systemic adverse effects. The injection sites for the digital nerve block are typically less painful than local infiltrations. Several techniques exist for digit anesthesia, making it a common and effective procedure in clinical settings.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

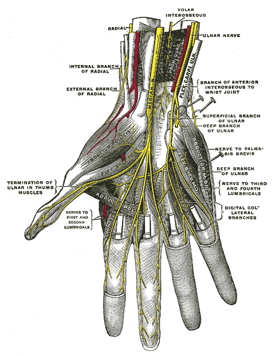

To perform this procedure effectively, healthcare providers must comprehensively understand regional anatomy. Digital nerve blocks are designed to anesthetize specific nerves originating at the wrist, branching from the median, radial, and ulnar nerves. Both dorsal and palmar nerves become apparent when the palm faces downward, and the fingertip is observed toward the hand. The dorsal nerves run adjacent to the digits at the 10- and 2-o'clock positions, while the palmar nerves travel at the 4- and 8-o'clock positions (see Image. Deep Palmer Nerves).[3] The palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve supplies the palmar surface of digits 1 through 3, the palmar radial surface of digit 4, and the dorsal nailbed of these digits up to approximately the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint. The palmar cutaneous branch of the ulnar nerve serves the ulnar half of digit 4 on both the palmar and dorsal surfaces, along with the entirety of digit 5, collectively called the palmar digital nerves. Meanwhile, the superficial branch of the radial nerve provides sensation to the dorsal surface of digits 1 through 3 up to roughly the DIP joint and the dorsal radial surface of digit 4.[3] Understanding the innervation patterns of digital nerves is clinically pertinent since multiple nerves contribute to finger sensation, occasionally necessitating the administration of anesthetic at various sites to ensure sufficient analgesia.[3]

The digital nerves of the toes extend along both sides of each toe and represent the terminal branches of the tibial and peroneal nerves. On the dorsal aspect, the medial portion of the great toe receives innervation from the medial dorsal cutaneous nerve, a branch of the superficial peroneal nerve. The dorsal-lateral aspect of the great toe and the dorsal-medial aspect of the second toe (first web space) are both served by branches of the deep peroneal nerve. The remaining lesser digits on their dorsal aspects receive innervation from the medial and intermediate dorsal cutaneous nerves, both stemming from the superficial peroneal nerve. In contrast, the lateral aspect of the fifth toe is innervated by the lateral dorsal cutaneous nerve, a terminal branch of the sural nerve. On the plantar side, all digits receive innervation from branches of the medial and lateral plantar nerves, originating from the tibial nerve after traversing the tarsal tunnel. Knowledge of the innervation patterns of digital nerves is of utmost clinical relevance, particularly given the presence of multiple nerves supplying sensation to each finger and toe, sometimes requiring the administration of anesthetic at various sites to ensure adequate analgesia.

Indications

Indications for a digital nerve block include:

- Immediate relief of pain to the digit

- Treatment of injuries to the digit, including the nail and nailbed

- Repair of complex lacerations to the digit

- Reduction of phalangeal dislocation

- Reduction of phalangeal fracture

- Drainage of digital infections of the fingertip (felon) and nail (paronychia)

- Removal of the nail plate

- Removal of an entrapped ring or other jewelry

- Foreign body removal

Contraindications

Contraindications to a digital nerve block include but are not limited to:

- Patient refusal

- Infection at the injection site, which could result in inoculation of a deeper or intravascular infection

- Distortion of landmarks

- Allergy to local anesthetics

While traditional teaching advocates for performing digital blocks without epinephrine due to concerns about vasoconstriction and potential distal necrosis, recent studies do not support this occurrence.[4][5]

Exercise caution when administering amide-based local anesthetics to patients with end-stage liver disease, as these agents are metabolized in the liver. A study revealed decreased ropivacaine clearance in chronic end-stage liver disease. However, considering a standard dose at the lowest effective level for a single block may be appropriate for patients with end-stage liver disease, with close monitoring due to the potential for systemic toxicity.[6]

Equipment

Required equipment for this procedure includes:

- Anesthetic agent: selection depends on the intended duration of the block (see below) and the patient's reported allergies

- 25 to 30 gauge needle for injection

- 18 to 22 gauge needle for medication draw

- 5 or 10 mL syringe

- Skin cleansing agents, such as alcohol prep pads or chlorhexidine 2%

- Access to lipid emulsion solution in case of local anesthetic systemic toxicity [7]

The anesthetic choice should be tailored to the length of the desired analgesia. The most commonly used anesthetics are lidocaine (1.5-2 hours), lidocaine with epinephrine (2-6 hours), bupivacaine (2-4 hours), and mepivacaine (3-5 hours). In a double-blinded randomized control trial, the incorporation of epinephrine 1:100,000 with local anesthetics versus local anesthetics alone was compared for finger or toe blocks. The trial found subjects with epinephrine had a significantly lower mean onset time. The authors concluded that using local anesthetics with epinephrine allows for a more rapid onset of action, a longer duration of anesthesia, and more significant hemostasis due to the vasoconstrictive effect of epinephrine.[8]

Personnel

Digital nerve blocks only require 1 provider in a cooperative patient. Providers should consider an assistant for uncooperative or pediatric patients to help stabilize the patient.

Preparation

Before initiating the nerve block, it is crucial to educate the patient thoroughly, providing detailed information about the procedure and ensuring they are well informed about potential risks and benefits. Obtain informed consent from the patient before commencing the procedure. Before administration, meticulously verify the expiration status of the local anesthetic vial, confirming the absence of allergies to the injectable agent in the patient. Additionally, ensure that all necessary equipment is readily available at the bedside to facilitate a smooth and efficient procedure.

Technique or Treatment

Depending on the treatment, various approaches can be used for a digital nerve block including the following:

- Web-Space block: This technique proves highly effective in achieving comprehensive anesthesia with minimal discomfort.

- Position the patient's hand on a sterile field, palm down.

- Hold the syringe perpendicular to the digit and gently insert the needle into the web space below the metacarpal-phalangeal (MP) joint.

- Gradually administer the anesthetic into the dorsal area of the web space.

- Slowly advance the needle directly toward the volar aspect of the web space, progressively infiltrating the surrounding tissues. Avoid piercing the volar aspect of the web space.

- Carefully withdraw the needle and repeat the procedure in the other web space of the affected digit.

- A similar approach is effective for the toes (excluding the great toe).

- Transthecal block: While effective with a single injection, it can be painful due to needle penetration of the sensitive palm skin. This is also referred to as the flexor tendon sheath digital block.

- Place the patient's hand, palm facing up, on a sterile field.

- Locate the flexor tendon sheath by palpating it at the distal palmar crease.

- Insert the needle at a 45-degree angle, just distal to the distal palmar crease.

- Ensure the anesthetic flows freely, repositioning the needle if resistance is encountered.

- Modified transthecal block

- Place the patient's hand with the palm facing up.

- Insert the needle at a 90-degree angle at the metacarpal crease until it contacts the bone.

- Slightly withdraw the needle and administer the anesthetic.

- During the injection, use the nondominant hand to apply proximal pressure at the injection site, directing the flow distally.

- Three-sided digital block: This method is particularly efficient for anesthetizing the great toe, although its applicability extends to any digit.

- Place the patient's extremity with the volar/plantar side facing downward.

- Begin by inserting the needle at a 90-degree angle, precisely at the medial aspect of the digit, just distal to the metatarsal-phalangeal joint.[9][10] Administer the anesthetic slowly while advancing the needle toward the volar/plantar side, ensuring it does not breach the volar skin.

- Gradually withdraw the needle and redirect it medially.

- Advance the needle slowly from the medial to lateral side while injecting the anesthetic, then withdraw the needle.

- Subsequently, administer another injection over the previously anesthetized skin at the lateral aspect of the digit, maintaining a 90-degree angle with the needle and advancing it from the dorsal to the ventral aspect, mirroring the medial approach.

- Four-sided ring block: This method is an extension of the 3-sided block. This technique is less favored because of the potential for ischemic complications.

- After the 3-sided block is performed, a third injection is performed.

- Insert the needle at the lateral aspect of the digit on the volar/plantar side and advance it medially as the anesthetic is slowly injected.

- Wing block: In cases where only the distal part of the digit is affected, this is a suitable alternative to a digital block.

- Place the extremity with the volar/plantar side facing downward.

- Hold the needle perpendicular to the long axis of the digit and at a 45-degree angle to the plane of the sterile field.

- Insert the needle 3 mm proximal to an imaginary point where a linear extension of the lateral and proximal nail folds would intersect.

- Administer the anesthetic along the proximal nail fold.

- Withdraw the needle and redirect it toward the lateral nail fold. If needed, repeat this step on the opposite side of the nail.

Additional facts to remember before performing a digital nerve block include those listed below.

- A dorsal approach is preferred due to the thinness of the skin in this location and decreased sensitivity.[11]

- Prolonged use of tourniquets is not advised.

- One should avoid using more than 3 to 4 mL of anesthetic solution to minimize pain from tissue distension secondary to fluid infiltration.

- The smallest gauge needle possible should be used to lessen pain.

- Before injecting the anesthetic, pull back on the plunger to ensure the needle isn't in a vessel.

- Always test for anesthesia by pricking the skin with a needle or pinching with forceps.

- The complete anesthetic effect may take 5 to 10 minutes. Wait at least 5 minutes after injection, and if sensation persists, wait an additional 5 minutes.

- One should not not inject directly into a nerve. Excessive pain or paresthesias may indicate the needle is too close to or within the nerve. Withdraw the needle 2 mm and reinject if this happens.

- Firm massage for approximately 30 seconds after local anesthetic infiltration can enhance the anesthetic's diffusion.

- In the hand, the dorsal and palmar nerves on each side can be anesthetized with a single needle puncture.[12][13] In the foot, the dorsal and plantar nerves on each side can also be anesthetized with a single needle puncture.

Complications

Complications of digital nerve blocks include but are not limited to:

- Infection

- Bleeding

- Increased pain

- Vascular injection of anesthetic

- Nerve injury, including neuropraxia or neurolysis

- Persistent tingling sensation (paresthesia)

- Allergic reaction

- Local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST)

- Vasovagal syncope

It is crucial to distinguish a LAST reaction from local or allergic reactions. Although LAST is rare, it must be ruled out after every injection due to its life-threatening potential. The earliest signs involve central nervous system (CNS) activation, accompanied by high blood pressure and tachycardia. CNS activation symptoms include perioral and facial paresthesia, metallic taste, dysarthria, diplopia, and auditory disturbances. Seizures may follow. As the symptoms progress, nervous and respiratory system depression may occur, with cardiovascular effects being the final manifestation, encompassing myocardial depression, bradycardia, hypotension, and heart failure.[14] Advanced cardiac life support-trained staff should be on hand in the event of cardiovascular collapse.[15]

Clinical Significance

Clinicians employ diverse methods to administer anesthesia, enabling effective maneuvering during procedures with minimal patient discomfort. Anesthesia is often approached multimodally to target pain transmission from the injury site to the cerebral cortex. A notable modality involves directing attention to the peripheral nerve, which transmits pain signals from tissues.[16] Targeting pain transduction at the tissue level can be achieved through drugs impeding the pain signaling pathway, such as opioids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or local anesthetic infiltration at the injury site.[17] However, local infiltration has drawbacks, including tissue distortion and patient discomfort due to the substantial anesthetic volume required.[17]

Alternatively, the peripheral nerve can be directly targeted through systemic analgesic agents like opioids, tricyclic antidepressants, or anesthetic agents in nerve block techniques. Nerve blocks can be applied proximal to the injury for broader anesthesia or regionally for targeted anesthesia near the affected tissue. The digital nerve block is a technique offering focused anesthesia that is generally better tolerated than local wound infiltration and requires a comparatively modest amount of anesthetic for a substantial anesthesia area.[17] This technique finds application in various procedures, including complex laceration repair, phalangeal dislocation or fracture reduction, drainage of digital infections like felon or paronychia, nail plate removal, or ring entrapment and removal. Proficiency with the anatomy and technique of the digital nerve block empowers clinicians to integrate it extensively into their practice.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The administration of digital nerve blocks necessitates a synergistic effort among physicians, nurses, and pharmacists—each contributing distinct skills and adhering to specific responsibilities. Physicians must possess advanced anatomical knowledge and procedural expertise for precise administration, ensuring optimal patient outcomes. They must also provide the patients with all risks and benefits associated with the procedure and obtain informed consent before performing it. Nurses are crucial in patient care coordination, monitoring patients during and after the procedure, and communicating effectively with the broader healthcare team. Pharmacists contribute by ensuring the correct selection and preparation of anesthetic agents, considering patient-specific factors and potential interactions. Interprofessional communication among these team members is paramount, fostering a cohesive approach prioritizing patient-centered care, safety, and overall team performance in digital nerve blocks.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Knoop K, Trott A, Syverud S. Comparison of digital versus metacarpal blocks for repair of finger injuries. Annals of emergency medicine. 1994 Jun:23(6):1296-300 [PubMed PMID: 8198304]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDe Buck F, Devroe S, Missant C, Van de Velde M. Regional anesthesia outside the operating room: indications and techniques. Current opinion in anaesthesiology. 2012 Aug:25(4):501-7. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e3283556f58. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22673788]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKim J, Lee YH, Kim MB, Rhee SH, Baek GH. Anatomy of the direct small branches of the proper digital nerve of the fingers: a cadaveric study. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2014 Aug:67(8):1129-35. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2014.04.026. Epub 2014 May 14 [PubMed PMID: 24908546]

Silva Neto OBD, Costa CFPA, Veloso FS, Kassar SB, Sampaio DL. Effects of vasoconstrictor use on digital nerve block: systematic review with meta-analysis. Revista do Colegio Brasileiro de Cirurgioes. 2020:46(6):e20192269. doi: 10.1590/0100-6991e-20192269. Epub 2020 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 31967242]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMantilla-Rivas E, Tan P, Zajac J, Tilt A, Rogers GF, Oh AK. Is Epinephrine Safe for Infant Digit Excision? A Retrospective Review of 402 Polydactyly Excisions in Patients Younger than 6 Months. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2019 Jul:144(1):149-154. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005719. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31246822]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJokinen MJ, Neuvonen PJ, Lindgren L, Höckerstedt K, Sjövall J, Breuer O, Askemark Y, Ahonen J, Olkkola KT. Pharmacokinetics of ropivacaine in patients with chronic end-stage liver disease. Anesthesiology. 2007 Jan:106(1):43-55 [PubMed PMID: 17197844]

Sepulveda EA, Pak A. Lipid Emulsion Therapy. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31751087]

Córdoba-Fernández A, González-Benítez J, Lobo-Martín A. Onset Time of Local Anesthesia After Single Injection in Toe Nerve Blocks: A Randomized Double-Blind Trial. Journal of perianesthesia nursing : official journal of the American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses. 2019 Aug:34(4):820-828. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2018.09.014. Epub 2019 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 30745078]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMorrison WG. Transthecal digital block. Archives of emergency medicine. 1993 Mar:10(1):35-8 [PubMed PMID: 8452611]

Hill RG Jr, Patterson JW, Parker JC, Bauer J, Wright E, Heller MB. Comparison of transthecal digital block and traditional digital block for anesthesia of the finger. Annals of emergency medicine. 1995 May:25(5):604-7 [PubMed PMID: 7741335]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYin ZG, Zhang JB, Kan SL, Wang P. A comparison of traditional digital blocks and single subcutaneous palmar injection blocks at the base of the finger and a meta-analysis of the digital block trials. Journal of hand surgery (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2006 Oct:31(5):547-55 [PubMed PMID: 16930788]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChoi S, Cho YS, Kang B, Kim GW, Han S. The difference of subcutaneous digital nerve block method efficacy according to injection location. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2020 Jan:38(1):95-98. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.04.031. Epub 2019 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 31005397]

Ahmad M. Efficacy of Digital Anesthesia: Comparison of Two Techniques. World journal of plastic surgery. 2017 Sep:6(3):351-355 [PubMed PMID: 29218285]

Vasques F, Behr AU, Weinberg G, Ori C, Di Gregorio G. A Review of Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity Cases Since Publication of the American Society of Regional Anesthesia Recommendations: To Whom It May Concern. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2015 Nov-Dec:40(6):698-705. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000320. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26469367]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFencl JL. Local anesthetic systemic toxicity: perioperative implications. AORN journal. 2015 Jun:101(6):697-700. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2015.03.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26025745]

Al-Chalabi M, Reddy V, Gupta S. Neuroanatomy, Spinothalamic Tract. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29939601]

Kehlet H, Dahl JB. The value of "multimodal" or "balanced analgesia" in postoperative pain treatment. Anesthesia and analgesia. 1993 Nov:77(5):1048-56 [PubMed PMID: 8105724]