Introduction

This presentation will provide an overview of the neural taste pathway. The associated nerves of this pathway will be analyzed, as well as the structures related to these nerves.

An examination of the conventional methods used to measure gustation will be discussed, and several examples of clinical pathologies associated with disturbances in taste.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

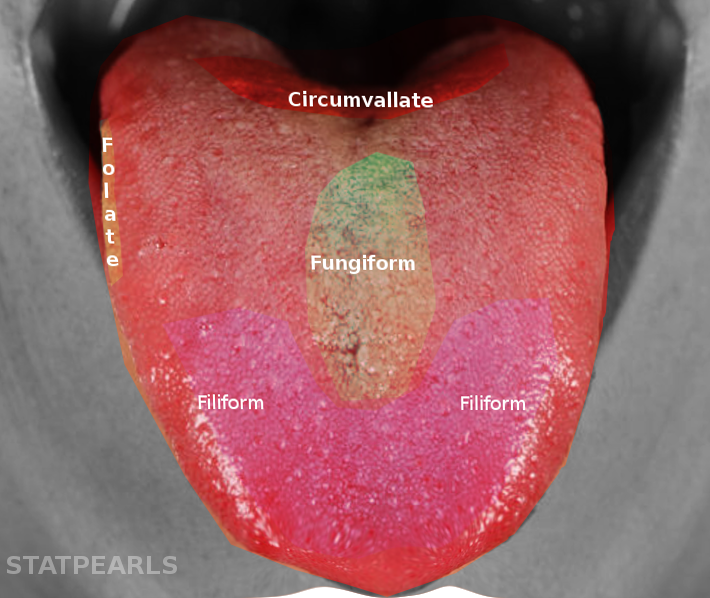

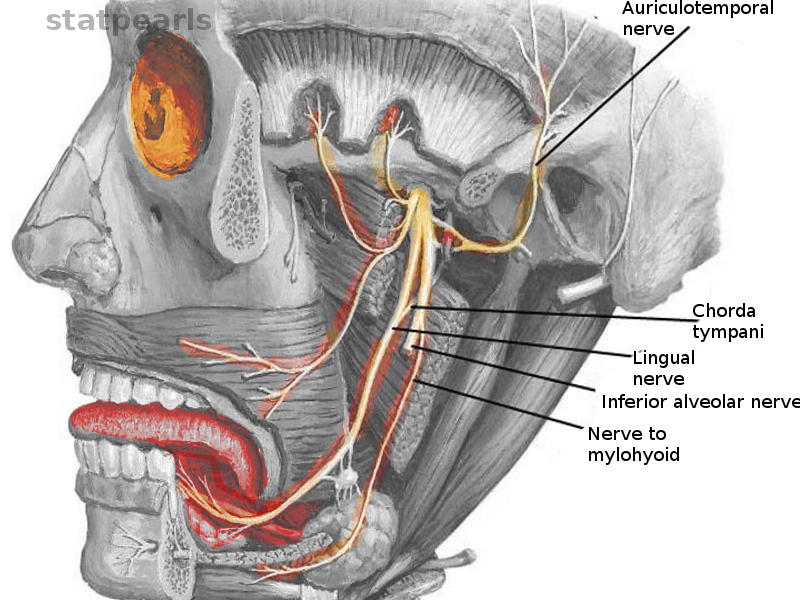

The neural taste pathway will undergo scrutiny from the perspective of starting within the tongue and moving away from it towards the brain. The three nerves associated with taste are the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII), which provides fibers to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue; the glossopharyngeal nerve (cranial nerve IX), which provides fibers to the posterior third of the tongue; and the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X), which provides fibers to the epiglottis region. Taste fibers categorize as special visceral afferent (SVA).

The branch of the facial nerve that innervates the anterior two-thirds of the tongue is the chorda tympani nerve. Another branch of the facial nerve, called the greater petrosal nerve, supplies innervation to taste buds of the soft palate. The cell bodies of the facial nerve associated with taste occur within the geniculate ganglion. Its central processes enter the brainstem at the pontomedullary junction and travel caudally to the medulla oblongata, where they synapse at the nucleus solitarius.

The cell bodies of the glossopharyngeal nerve associated with taste are in the inferior ganglion of the glossopharyngeal nerve (petrosal ganglion). The central processes of the glossopharyngeal nerve travel through the jugular foramen, enter the brainstem at the level of the rostral medulla and eventually synapse at the nucleus solitarius.

The cell bodies of the vagus nerve associated with taste exist in the nodose ganglion. Its central processes travel through the jugular foramen to the medulla and synapse at the nucleus solitarius.

At this point, fibers from all three of these nerves have synapsed at the nucleus solitarius. Specifically, the synapse occurs in the rostral part of the nucleus solitarius, known as the gustatory region of the nucleus.[1] The caudal area of the nucleus solitarius receives cardio-respiratory information, and it is known as the visceral region.

Next, the second-order fibers ascend ipsilaterally to the parvicellular division of the ventral posteromedial nucleus (VPMpc) of the thalamus, where the next synapse occurs.

The third-order fibers travel ipsilaterally through the posterior limb of the internal capsule to terminate in the frontal operculum, anterior insular cortex, and in the rostral part of the Brodmann area 3B.[2] The overall function of these third-order fibers is to provide discriminatory taste sensations.

Additionally, secondary fibers travel from the gustatory cortex to the posterolateral portion of the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC). This area is where the integration of taste and smell takes place, as well as the phenomenon of food reward.[3] The description of food reward is the enjoyment of a particular food when an individual is eating it.[4]

Surgical Considerations

There is a chance of facial nerve damage during surgeries for tumors in the region of the cerebellopontine angle and parotid region. The surgeon must take extra care to preserve the facial nerve and its branches during such procedures.

Clinical Significance

The clinician can examine the integrity of the nerves associated with taste (specifically the facial nerve and glossopharyngeal nerve) with a suprathreshold taste test. Edible strips placed on specific regions of the patient’s tongue contain the five taste qualities (sweet, salty, bitter, sour, umami). The strips provide stimulation slightly above the threshold for taste. If a patient can properly identify a taste, this is considered a normal result. This test has been proven to be decidedly sensitive for analyzing taste recognition.[5]

The electrical stimulation of the tongue through the use of a clinical electrogustometer can also be used to examine the taste threshold of patients. The examiner places electrodes on the taste buds of a patient, and the resulting action potentials are measured. However, feelings of pain have been reported by patients who have been examined by way of this method.[6]

There are many causes for diminished or altered taste sensations in an individual, such as medications that cause dysgeusia. Examples of these medications include agents such as acetazolamide, maribavir, and cisplatin.[7] Most often, changes in salivation resulting from taking a certain medication are the primary cause behind this adverse effect.

Relatedly, individuals who have Sjogren syndrome also report disturbances in taste. Sjogren syndrome is an autoimmune disorder in which a person’s immune system damages his or her own lacrimal glands and salivary glands (parotid gland, sublingual gland, and submandibular gland). The conclusion is that damage to the salivary glands results in a reduced outflow of saliva, which leads to the prevention of substances, like food, from reaching the taste buds.[8]

Another cause of altered or diminished taste is due to diabetes mellitus, which is especially true in individuals who suffer from undiagnosed or untreated diabetes. Recent studies have considered the disturbances in taste to be an early indicator of the disease. Among newly diagnosed patients, one of the most common complaints within this population is the blunted taste response when eating food that they may have typically experienced as sweet-tasting in the past. When patients receive appropriate treatment for their high blood glucose, their taste disturbances can sometimes partially reverse. The specific cause for taste alteration in this population is still not fully known; though, the thinking is that progressive damage to the facial nerve, glossopharyngeal nerve, and/or vagus nerve may be the leading culprit when it comes to taste disturbances in diabetic patients.[9]

A vestibular schwannoma (also referred to as an acoustic neuroma), which is a benign tumor that grows into the cerebellopontine angle (CPA), can cause loss of taste in the anterior two-thirds of the tongue on the ipsilateral side.[10] In addition to the facial nerve, this tumor most commonly impinges on the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V), which can cause ipsilateral loss of sensation to the face, and the vestibulocochlear nerve (cranial nerve VIII), which can cause ipsilateral hearing loss. Besides an ipsilateral loss of taste sensation of the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, impingement of the facial nerve caused by this tumor can cause ipsilateral paralysis of the muscles of facial expression (leading to Bell palsy), paralysis of the stapedius muscle (leading to hyperacusis), and decreased secretions of the submandibular gland, sublingual gland, and lacrimal gland.

Media

References

Suwabe T, Bradley RM. Characteristics of rostral solitary tract nucleus neurons with identified afferent connections that project to the parabrachial nucleus in rats. Journal of neurophysiology. 2009 Jul:102(1):546-55. doi: 10.1152/jn.91182.2008. Epub 2009 May 13 [PubMed PMID: 19439671]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKaas JH. The future of mapping sensory cortex in primates: three of many remaining issues. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences. 2005 Apr 29:360(1456):653-64 [PubMed PMID: 15937006]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSmall DM, Bender G, Veldhuizen MG, Rudenga K, Nachtigal D, Felsted J. The role of the human orbitofrontal cortex in taste and flavor processing. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2007 Dec:1121():136-51 [PubMed PMID: 17846155]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRogers PJ, Hardman CA. Food reward. What it is and how to measure it. Appetite. 2015 Jul:90():1-15. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.02.032. Epub 2015 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 25728883]

Smutzer G, Lam S, Hastings L, Desai H, Abarintos RA, Sobel M, Sayed N. A test for measuring gustatory function. The Laryngoscope. 2008 Aug:118(8):1411-6. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31817709a0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18528309]

McClure ST, Lawless HT. A comparison of two electric taste stimulation devices. Physiology & behavior. 2007 Nov 23:92(4):658-64 [PubMed PMID: 17573078]

Douglass R,Heckman G, Drug-related taste disturbance: a contributing factor in geriatric syndromes. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien. 2010 Nov; [PubMed PMID: 21075995]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNegoro A, Umemoto M, Fujii M, Kakibuchi M, Terada T, Hashimoto N, Sakagami M. Taste function in Sjögren's syndrome patients with special reference to clinical tests. Auris, nasus, larynx. 2004 Jun:31(2):141-7 [PubMed PMID: 15121223]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBhandare NN, Keny MS, Nevrekar RP, Bhandare PN. Diabetic Tongue - Could it be a Diagnostic Criterion? Journal of family medicine and primary care. 2014 Jul:3(3):290-1. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.141654. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25374875]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBoessert P, Grüttner C, van Ewijk R, Haxel B. [Changes in taste ability in patients with vestibular schwannoma]. Laryngo- rhino- otologie. 2014 Jul:93(7):450-4. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1375658. Epub 2014 Jul 7 [PubMed PMID: 24999665]