Introduction

Nocardiosis is a disease affecting different organs of the body. It is an infectious disease caused by Nocardia, which is a gram-positive bacillus with a branching hyphae morphology found throughout the environment in soil, decomposing vegetation, and other organic matter. It is also found in both fresh and salt water. Nocardia is typically weak acid-fast positive on microscopy with staining. Classically, Nocardia manifests as an opportunistic infection in immunocompromised hosts and can impact nearly every part of the human body including skin and skin structures, the pleural or pulmonary system, or it can be a disseminated disease impacting other organ systems.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Pulmonary nocardiosis and disseminated forms of the infection are opportunistic diseases occurring mainly in patients deficient in T cell-mediated immunity. Patients with the greatest susceptibility to this include those with solid organ transplant and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, HIV-infected patients, patients taking corticosteroids chronically, or patients with ongoing malignant processes. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis may occur in immunocompetent patients who have experienced a direct inoculation of the microorganism into the skin structures from a traumatic event. This is seen most commonly in those working in rural areas involving in agricultural activities. While rare, post-surgical wound infections may occur if non-sterile equipment is used. Pulmonary forms of nocardiosis are induced via aerosolized inoculation of the bacterium into the airways. Dissemination throughout the remainder of the body may occur from either of these initial inoculations.[2]

Risk factors for acquiring Nocardia include the following:

- Alcoholism

- Chronic lung disease (esp patients with pulmonary alveolar proteinosis)

- Solid-organ transplant

- Use of corticosteroids

- Hematological malignancy

- Collagen vascular disease (lupus)

- Renal failure

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Whipple disease

- HIV

Epidemiology

Nocardiosis has an infection incidence rate of approximately 500 to 1000 cases per year in the United States. There is no racial predilection; however, it has been observed that males are at a higher risk for infection than females with an incidence of 3:1. There is no age predilection for infection; however, those impacted are, on average, in their 40s.

Pathophysiology

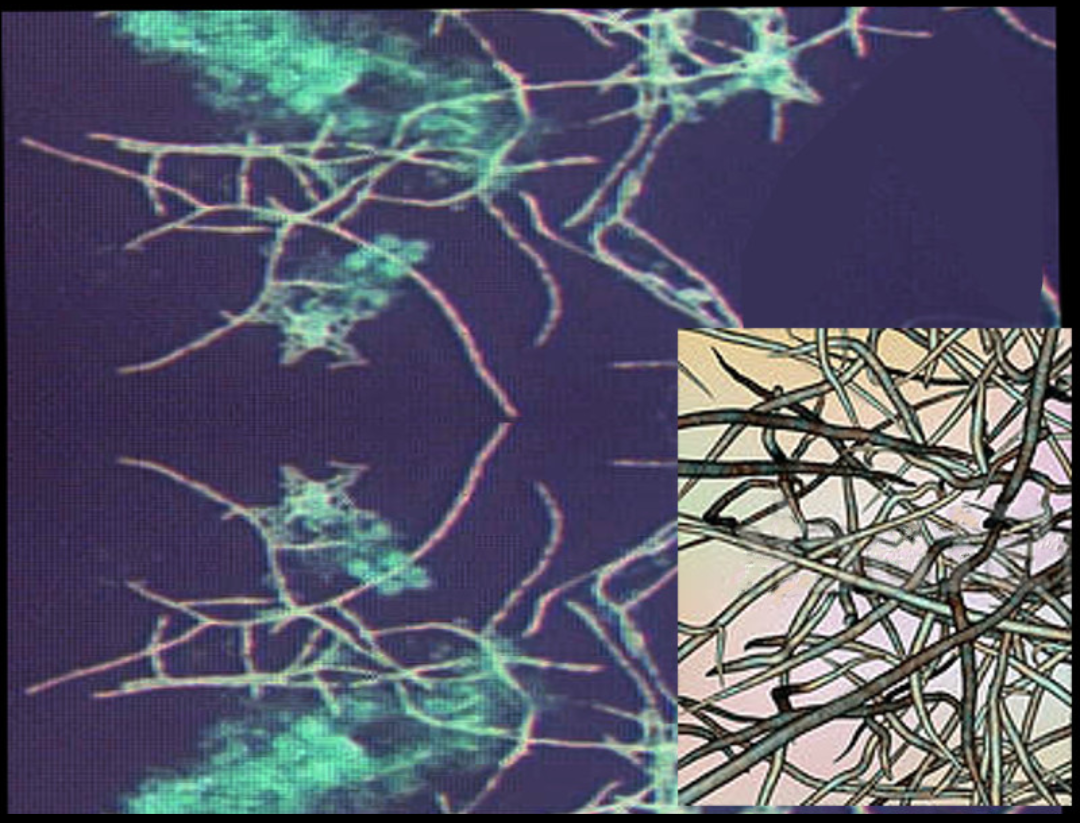

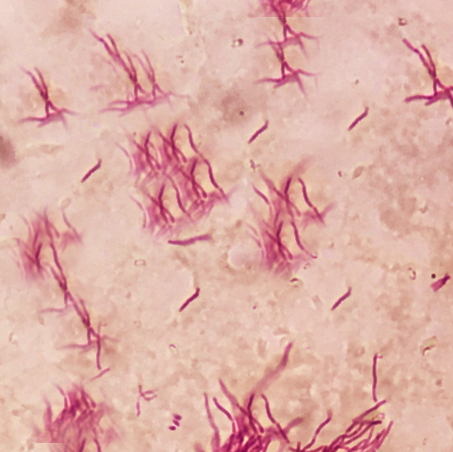

Nocardia are ubiquitous saprophytes found in water, decaying organic matter and soil. Out of the 100 known subtypes, only a dozen have been identified to cause disease in humans. Nocardia has a typical filamentous, beading and branching morphology easily seen on microscopy.

The cutaneous disease is usually acquired after a local injury to the skin. In the healthy population, the cutaneous disease is not serious but in immunocompromised hosts, there is the potential to spread to other organs. The localized infection may present with abscess formation and ulcers. Pleuropulmonary nocardiosis is acquired after inhalation of contaminated aerosolized droplets. The majority of patients who develop lung disease are immunocompromised.

Histopathology

Nocardia is a genus of aerobic actinomyces found throughout the world in both salt and freshwater sources as well as various dirt and soil types. There are more than 100 species defined. However, approximately 30 of these carry significance to human disease. Histopathologically, Nocardia is viewed as a branching, filamentous, gram-positive organism with weak acid-fast, positive properties.

History and Physical

The presentation of nocardiosis is variable and depends greatly on the organ systems involved in the infection.

Primary Cutaneous Nocardiosis

This form of nocardiosis presents in the form of skin and skin structure infections. History typically involves a known traumatic event with breaking the skin in a “dirty” environment. Patients will present with complaints of an erythematous, a tender, warm, swollen area around the traumatic site that appears similar to simple cellulitis. They may complain of tender nodules or abscesses in the vicinity. Purulent drainage may be present as well. In more progressed cases, suppurative necrosis formation occurs. Clinically, this form of infection is indistinguishable from other bacterial pathologies.

Lymphocutaneous Nocardiosis

Presents similarly to primary cutaneous nocardiosis with the addition of ascending regional lymphadenopathy. Lymph nodes may ulcerate to have weeping necrotic or purulent drainage in severe cases.

Pulmonary Nocardiosis

May present as either an acute infection, a subacute infection, or a chronic infection. Pulmonary nocardiosis is clinically determined with the findings of inflammatory bronchial mass or pneumonia with fever, productive cough, dyspnea, or chest pain. Pulmonary disease may be complicated by cavitation, abscess formation, pleural effusion, or empyema.

Disseminated Disease

Deep abscesses are possible to form at any disseminated site. Signs and symptoms in these scenarios are tailored to the location of the abscess. Non-central nervous system (CNS) findings will at a minimum typically include fever. Dissemination to the CNS will additionally show signs of slow growth mass lesion effect with neurological signs such as numbness or muscular weakness representative of the region of the brain or spinal cord impacted. Signs of meningitis such as headache, stiff neck, or altered mental status may be present as well.[3],[4]

Evaluation

Essential evaluation when suspecting nocardiosis should include bacterial cultures of the infectious sites, skin biopsy, purulent discharge, sputum, deep abscess or pleural aspirates, and others. Nocardia is notoriously slow-growing, so suspicion should be shared with the laboratory to allow for ample growth time of up to 3 to 5 days. Additionally, blood cultures should be collected whenever a disseminated or pulmonary infection is suspected.

Imaging studies should include plain film chest radiography and CT chest for pulmonary infection. While there are no classical findings on radiography, they may show irregular nodules, cavitation, diffuse alveolar pulmonary infiltrates, lung abscess, or pleural effusion. Additional imaging should include CT or MRI of the brain to evaluate for disseminated Nocardia to the CNS. If meningeal signs are present, lumbar puncture with an evaluation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) should be performed.[5][6]

Treatment / Management

The primary treatment for nocardiosis is characterized by a minimum of 6 months and should extend for at least 1 month after symptoms of infection have resolved after the use of antibiotics. Skin infections in an immunocompetent patient may be managed with monotherapy. For pulmonary or disseminated disease, empiric therapy should consist of 2 to 3 agents. However, there are no therapies proven to be superior at this time. As such, antibiotics should be tailored following culture and sensitivity patterns. Potential agents to use include trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, amikacin, imipenem, meropenem, third-generation cephalosporins such as ceftriaxone and cefotaxime, minocycline, extended-spectrum fluoroquinolones such as moxifloxacin, linezolid, tigecycline, dapsone, and clarithromycin.

Sulfonamides are the first-line agents, especially sulfadiazine which has good penetrability into the brain. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is also preferred by some clinicians. For severe disease, combination drug therapy is recommended

Simple abscesses require surgical incision and drainage. Brain abscesses will require surgical intervention if the mass effect is large or if there is no improvement after 2 weeks of antibiotic therapy.

Close monitoring is essential for up to 1 year following cessation of antibiotics to detect relapse infection. Likewise, radiographic studies and laboratory studies should be monitored.[7],[2]

Differential Diagnosis

Nocardiosis clinically appears similar to many other viral, bacterial, or fungal infections as well as several types of malignancy. Care should be given to distinguish it from the following:

- Bacterial pneumonia

- Cellulitis

- Community-acquired pneumonia

- Fungal pneumonia

- Glioblastoma multiforme

- Histoplasmosis

- Kaposi sarcoma

- Lung abscess

- Mycobacterium avium complex

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- Parapneumonic pleural effusions

- Empyema thoracis

- Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia

- Sporotrichosis

- Tuberculosis

- Viral pneumonia [8],[9],[10]

Prognosis

The prognosis of nocardiosis is variable. It depends upon the organ infected, duration, immunological state of the person, and severity of the infection. Skin and soft tissue have a much better prognosis as compared to pleuropulmonary and systemic disseminated nocardiosis infection when appropriate treatment is given. The majority of patients with skin nocardiosis can be cured with prompt treatment. However, in patients with brain abscess cure rates are less than 60%

Complications

- Lung infection, empyema

- Brain abscess

- Meningitis

- Osteomyelitis

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

The treatment of nocardiosis should be for at least for 6 months. In patients who are immunocompromised, the treatment has to be continued until the symptoms subside.

Consultations

- Infectious disease

- Thoracic surgeon

- General surgeon

- Oncologist

- Neurosurgeon

- Pulmonologist

Deterrence and Patient Education

Some data indicate that prophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in AIDS patients with a low CD 4 count may decrease the risk of nocardiosis. [11]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Nocardia is ubiquitous in the environment and can cause a variety of infections. However, the clinical presentation and outcomes do vary depending on the immune status and patient comorbidity.

Given the severity and rarity of nocardial infections in immunocompromised patients and the high rate of dissemination and abscess formation of the bacterium, it is essential to utilize an interprofessional approach toward evaluation and treatment to yield the best results. Some examples of specialties that should be involved in the decision-making process to determine optimal treatment include primary care physicians, infectious diseases specialists, general, neurological, and/or cardiothoracic surgeons, pulmonologists, neurologists, critical care physicians, and/or ophthalmologists. Nurses need to be familiar with the disease process to coordinate patient education. Pharmacists need to be involved in the selection and maintenance of drug therapy. Over the past decade, it has become clear that Nocardia has started to develop resistance to many of the common antibiotics like the cephalosporins and sulfonamide. Because of the potential resistance to sulfonamides, it is important to start treatment based on drug susceptibility results.

Outcomes

There are only small cases series on outcomes of Nocardia treatment. Individuals with intact immunity usually have a good outcome, but transplant patients or those with HIV who are immunosuppressed have a guarded prognosis. The management of a transplant patient requires an interprofessional approach if high morbidity and mortality is to be avoided. [12] (Level C)

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

This image depicts the feet, ankles, and lower legs of a patient, who had presented with an infection known as nocardiosis, a form of actinomycosis, due to the bacterium, Nocardia somaliensis, which had affected the left foot and ankle, causing severe swelling and deformation of the normal structural contours. Contributed by the CDC/ Dr. Hardin

References

Wilson JW. Nocardiosis: updates and clinical overview. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2012 Apr:87(4):403-7. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.11.016. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22469352]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMazzaferri F, Cordioli M, Segato E, Adami I, Maccacaro L, Sette P, Cazzadori A, Concia E, Azzini AM. Nocardia infection over 5 years (2011-2015) in an Italian tertiary care hospital. The new microbiologica. 2018 Apr:41(2):136-140 [PubMed PMID: 29806691]

Singh AK, Shukla A, Bajwa R, Agrawal R, Srivastwa N. Pulmonary Nocardiosis: Unusual Presentation in Intensive Care Unit. Indian journal of critical care medicine : peer-reviewed, official publication of Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine. 2018 Feb:22(2):125-127. doi: 10.4103/ijccm.IJCCM_472_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29531457]

Arjun R, Padmanabhan A, Reddy Attunuru BP, Gupta P. Disseminated nocardiosis masquerading as metastatic malignancy. Lung India : official organ of Indian Chest Society. 2016 Jul-Aug:33(4):434-8. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.184920. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27578940]

Thirouvengadame S, Muthusamy S, Balaji VK, Easow JM. Unfolding of a Clinically Suspected Case of Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2017 Aug:11(8):DD01-DD03. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/25788.10404. Epub 2017 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 28969125]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKim J, Kang M, Kim J, Jung S, Park J, Lee D, Yoon H. A Case of Nocardia farcinica Pneumonia and Mediastinitis in an Immunocompetent Patient. Tuberculosis and respiratory diseases. 2016 Apr:79(2):101-3. doi: 10.4046/trd.2016.79.2.101. Epub 2016 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 27066088]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePaige EK, Spelman D. Nocardiosis: 7-year experience at an Australian tertiary hospital. Internal medicine journal. 2019 Mar:49(3):373-379. doi: 10.1111/imj.14068. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30091232]

Aljuboori Z, Sharma M, Altstadt T. Diffuse Nocardial Spinal Subdural Empyema: Diagnostic Dilemma and Treatment Options. Cureus. 2017 Oct 24:9(10):e1795. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1795. Epub 2017 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 29282439]

McHugh KE, Sturgis CD, Procop GW, Rhoads DD. The cytopathology of Actinomyces, Nocardia, and their mimickers. Diagnostic cytopathology. 2017 Dec:45(12):1105-1115. doi: 10.1002/dc.23816. Epub 2017 Sep 9 [PubMed PMID: 28888064]

Secchin P, Trope BM, Fernandes LA, Barreiros G, Ramos-E-Silva M. Cutaneous Nocardiosis Simulating Cutaneous Lymphatic Sporotrichosis. Case reports in dermatology. 2017 May-Aug:9(2):119-129. doi: 10.1159/000471788. Epub 2017 Aug 17 [PubMed PMID: 29033815]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBoamah H, Puranam P, Sandre RM. Disseminated Nocardia farcinica in an immunocompetent patient. IDCases. 2016:6():9-12. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2016.08.003. Epub 2016 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 27617207]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWang HK, Sheng WH, Hung CC, Chen YC, Lee MH, Lin WS, Hsueh PR, Chang SC. Clinical characteristics, microbiology, and outcomes for patients with lung and disseminated nocardiosis in a tertiary hospital. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association = Taiwan yi zhi. 2015 Aug:114(8):742-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2013.07.017. Epub 2013 Sep 3 [PubMed PMID: 24008153]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence