Introduction

Orbital cellulitis is an infection causing inflammation of the orbital contents posterior to the orbital septum. These contents include the periorbital fat and extra-ocular muscles, but exclude the involvement of the globe itself. [1] In distinction, preseptal (periorbital) cellulitis is an infection anterior to the orbital septum, mainly involving the eyelids. [2]

Although periorbital cellulitis is a much more common entity, especially in children, it is important to recognize the differences of orbital cellulitis as its complications are much more severe and can become life-threatening. [2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The most common causative organisms are Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species, specifically Staphylococcus aureus and group A Streptococcus, with increasing incidence of MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) being of great concern.[1], 5 Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae historically have been major components of this type of infection; however, their incidence has significantly decreased since the introduction of vaccines against these organisms. [1] That being said, worldwide, H. Influenza type B has been associated with 20% of orbital cellulitis cases associated with subperiosteal abscess formation. [3]

Non-spore forming anaerobic bacteria are also associated with orbital cellulitis but at a much lower rate than the previous organisms. Specifically, Fusobacterium and Peptostreptococcal species are the most commonly associated anaerobes causing orbital cellulitis in the United States. [1], [3]

One other important consideration is the involvement of fungal species in the immunocompromised patient. Mucormycosis and Aspergillosis species are the most common associated fungal etiologies of orbital cellulitis. Special scenarios to note are the associations of necrotizing sinusitis by mucormycosis in the diabetic patient in Ketoacidosis and Aspergillus infection of the orbit in immunosuppressed patients due to HIV infection or severely neutropenic patients. However, fungal orbital cellulitis has a much slower and chronic course compared to its bacterial counterpart. [3]

Epidemiology

Overall, orbital cellulitis is much more common in younger children as opposed to older children or even adults. This is because most cases of orbital cellulitis are preceded by bacterial rhinosinusitis or an upper respiratory infection which are most commonly seen in younger children. [1] According to some sources, 86% to 98% of cases of orbital cellulitis are found to have coexisting rhinosinusitis, specifically cases of ethmoid sinusitis are most commonly involved. [1], [3], [2]

Due to its coexistence with rhinosinusitis, orbital cellulitis is most predominant in the winter months.

Other prospective causes include cases following ophthalmic surgery or peribulbar anesthesia, trauma or foreign body, severe dacryocystitis, or even infections of the teeth, face, or middle ear can spread and involve the orbit. [3]

Pathophysiology

Most cases of orbital cellulitis are bacterial and often involve the causative bacteria that can cause sinusitis since the direct extension is the most common mechanism due to small perforations were seen in the orbital septum. Hematogenous extension through the orbital veins draining the paranasal sinuses is also a proposed mechanism due to the lack of valves in these structures. [1]

History and Physical

It is imperative to distinguish preseptal and orbital cellulitis, and a good history and physical exam can most often serve this goal.

For patients with orbital cellulitis, it is very common to find a history of recent or concurrent acute sinusitis or upper respiratory tract infection. This is followed by acute eyelid edema and redness with rapid progression of eye pain with movement, decrease vision, and eye redness such as conjunctival injection. These symptoms are often accompanied by systemic signs of fever, general malaise, and loss of appetite. [1], [3]

It should also be mentioned that a history of past sinus or dental disease, as well as recent ophthalmological surgery, should be explored as these can be highly associated with orbital cellulitis. [3]

A family history of autoimmune disorders and malignancies should also be addressed to rule-out other possible etiologies that may mimic orbital cellulitis by presenting as unilateral proptosis.

The most common physical exam findings of orbital cellulitis include unilateral eyelid edema and erythema, warmth, and eyelid tenderness on examination. Accompanying these may be the presence of blurred vision, proptosis, chemosis (edema of the conjunctiva), and ophthalmoplegia (paralysis of extraocular movements). Depending on the amount of eyelid swelling, the physical exam may become challenging, and joint examinations with ophthalmology can be very beneficial, especially when assessing fundoscopic findings. [1], [3] Worrisome findings on the fundoscopic exam include optic disc swelling with orbital nerve edema, engorgement of disc vessels, or presence of retinal artery thrombi, all of which may point to an intracranial extension of infection. [3]

Evaluation

An organized and systematic evaluation should be performed when evaluating a patient for concerns of orbital cellulitis. Though a history of constitutional symptoms and vital signs should heighten clinical suspicion, nothing replaces a thorough physical exam. [3]

Blood work such as a complete blood count (CBC) may show leukocytosis with a neutrophil predominance, though this is not needed for diagnosis. Some reports suggest obtaining blood cultures to assess for possible underlying bacteremia, but there has been a very low yield of less than 20% in most reports. The most definitive test to identify the causative agent is a surgical aspiration of a subperiosteal or orbital abscess if surgery is necessary. However routine aspiration or biopsy is not recommended and not needed to start treatment. [1], [3], [4], [2]

Imaging is another potentially useful, yet somewhat controversial topic. Some studies advocate for the routine use of computed tomography (CT) in the initial evaluation of patients with clinically confirmed or suspected orbital cellulitis to evaluate the orbital and paranasal sinus contents better. Of specific importance is the potential recognition of subperiosteal abscess formation which may show the need for possible surgical intervention. [1], [5], [3], [6] If a CT scan is used, it should be noted that intravenous (IV) contrast may be very helpful in differentiating true abscess formation from the inflammatory phlegmatic involvement of orbital tissues. If not used during the initial evaluation, clinicians do recommend the use of CT in the assessment of patients not improving or worsening clinically after 48 hours of IV antibiotic treatment. [5], [3], [6]

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is another good option for radiological evaluation with limiting radiation exposure of CT; this is especially true in pediatric patients. Though MRI does provide better resolution of the orbital tissues, it may be more suitable for the adult population given the length of study may require sedation and coordination with anesthesia for proper study in children. [3]

Ophthalmology evaluation should never be underestimated in a patient with orbital cellulitis and consultation should be part of the initial evaluation. A proper comprehensive ophthalmologic assessment including visual function, testing afferent pupillary defect, and ophthalmoscopy to assess optic nerve edema and venous tortuosity should be performed, especially in patients with severe eyelid swelling and edema. [1], [3]

Treatment / Management

Medical Management

Once the diagnosis of orbital cellulitis is confirmed, prompt antibiotic treatment is paramount. Due to the rare, but serious, complications associated with this condition, intravenous antibiotics should be started for empiric coverage of the most common associated organisms which usually include gram-positive organisms such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus and gram-negative bacilli. Should there be a concern for intracranial extension, anaerobic coverage should also be included. One should always keep in mind the local trends of antimicrobial susceptibility, especially regarding MRSA coverage. [1]

Empiric treatment most often includes a combination of IV antibiotics with broad coverage for the organisms discussed above. In patients with normal renal function, Vancomycin IV should be started with the addition of one of the following antibiotics: ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, ampicillin-sulbactam, or piperacillin-tazobactam. Should an intracranial extension be suspected, a combination of vancomycin plus ampicillin-sulbactam or piperacillin-tazobactam should be given, and no further therapy is needed. If ceftriaxone or cefotaxime were added to vancomycin, however, then metronidazole should be added for triple therapy for added anaerobic coverage. [5], [3], [6](B2)

Should the patient have a simultaneous sinusitis, it is also recommended to aid with nasal congestion by administration of oxymetazoline nasal spray for 3 days as well as saline nasal irrigation to help drainage of the sinuses and aid in the recovery of the underlying cause of the orbital cellulitis. [1], [3]

Special consideration should be given to patients with severe penicillin and/or cephalosporin allergy. In this case, a combination of vancomycin with either ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin may provide adequate coverage of the presumed causative organisms. However, it should be noted that Fluoroquinolone penetration into the central nervous system (CNS) has been shown to be quite low and therefore poor for preventing the spread of infection and intracranial complications. [1]

Once clinical improvement has been noted, most often after 48 to 72 hours of IV antibiotics, it is suitable to transition the patient to oral antibiotics for continued treatment on an outpatient basis. Oral treatment regimens include the use of MRSA covering agents such as clindamycin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, plus one of the following for better Streptococcus and anaerobic coverage: amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, cefpodoxime, or cefdinir. [1], [3]

Total antibiotic treatment usually covers a 14-day course; however, complicated cases may be treated for up to 21 days. [1]

Surgical Management

Surgical management is reserved for special circumstances, primarily the presence of large subperiosteal abscesses or orbital abscesses. One clue to the necessity of surgical intervention could be changed in visual function and lack of improvement in fever, swelling, proptosis, or pain. These clues should guide prompt imaging studies to re-evaluate the presence of a new or enlarging abscess. [1], [3]

In general, subperiosteal abscess greater than 10 mm in size should be evaluated by the ophthalmology surgical service and would likely need drainage. Orbital abscesses regardless of size should also be evaluated by the surgical team, and any intracranial extension of the infection should be evaluated by the surgical team for any possible drainage or shunts that may be required for evacuation of pus formation. [1], [5], [3](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

In the absence of the signs and symptoms of orbital cellulitis like eyelid edema, proptosis, and pain with eye movement or other systemic signs such as fever and an overall toxic appearance, other causes of proptosis should be explored. This includes neoplasms, inflammatory lesions, autoimmune diseases, and orbital bone anomalies, among others. [1]

The most common primary neoplasms associated with proptosis are rhabdomyosarcoma and retinoblastoma, with neuroblastoma being the most common metastatic neoplasm. However, melanoma has also been known to metastasize to the orbit or eye itself.

Autoimmune diseases such as orbital pseudotumor (idiopathic orbital inflammatory disease), Tolosa-Hunt syndrome, and Exophthalmos secondary to Graves' disease may be ruled out based on history lab work and imaging. [1]

Imaging and exam can also evaluate other lesions such as foreign bodies, hemorrhagic cysts, aneurysmal bone cysts, ossifying fibromas, and pseudoaneurysms of orbital bones and be ruled-out. [1], [5]

Prognosis

The overall prognosis of orbital cellulitis is very positive if the diagnosis is made quickly and treatment is started in a timely fashion. Clinical improvements are usually seen within the first 24 to 48 hours of initiating IV antibiotics in uncomplicated cases.

Though complications are rare, without prompt treatment, they can be severe as discussed below.

Most cases do respond well to IV antibiotics, and resolution is most often done as an outpatient by continuing oral antibiotics. However, with large subperiosteal abscess formation (greater than 10 mm) or orbital abscess formation, or nerve and vascular compromise are present surgical intervention may be necessary. [1]

Complications

The most common complications of orbital cellulitis involve abscess formation, specifically subperiosteal abscesses. These are most commonly seen involving the medial wall or floor of the orbit as they are the thinnest orbital components. Orbital abscesses inside the orbit itself, however rare, are still possible and can be a cause of persistent fever despite 48 hours of IV antibiotics. [1], [3]

Deterioration of visual acuity or inability to see colors is also a worrisome finding given its association with optic disc edema from retinal artery occlusion due to septic emboli. Lack of afferent pupillary response is also concerning as it may point toward optic nerve involvement. [1], [5], [3]

More serious complications include those that extend into the CNS. These include cavernous sinus thrombosis, meningitis, and intracranial abscess. Of special consideration is the new finding of sixth nerve palsy in the setting of acute orbital cellulitis that is not improving in antibiotics is worrisome for cavernous sinus thrombosis given the anatomy of cranial nerve VI running on the wall of the cavernous sinus. [1], [3]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Orbital cellulitis causes an infection of the orbital contents posterior to the orbital septum. Although periorbital cellulitis is a much more common entity, especially in children, it is important to recognize the differences of orbital cellulitis as its complications are much more severe and can become life-threatening. The health professional team must be aware of this entity as a possibility in any patient presenting with the signs and symptoms of orbital eye involvement and act quickly for the best possible patient outcome. [Level 5]

Media

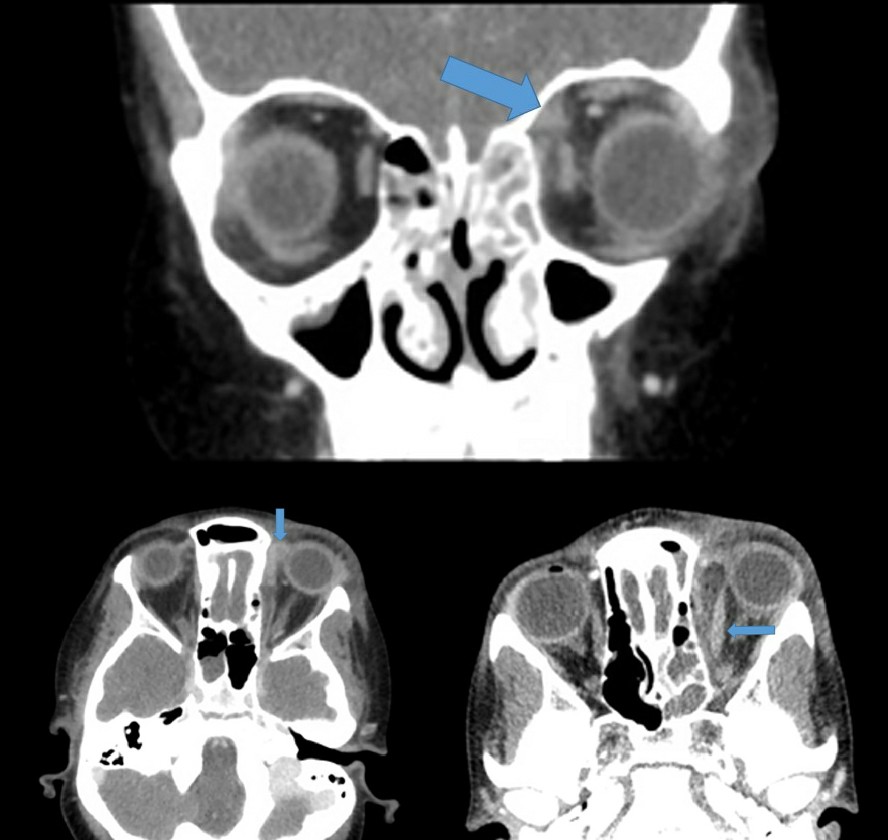

(Click Image to Enlarge)

14-year-old female presents with swelling of the right periorbital tissues developing over one week with nasal congestion, pain, double vision and difficulty opening the eyelids and decreased vision. Note the right nasal discharge. Diagnosis cellulitis of the right orbit. Contributed by Prof Bhupendra C. K. Patel MD, FRCS

References

Hauser A, Fogarasi S. Periorbital and orbital cellulitis. Pediatrics in review. 2010 Jun:31(6):242-9. doi: 10.1542/pir.31-6-242. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20516236]

Nageswaran S, Woods CR, Benjamin DK Jr, Givner LB, Shetty AK. Orbital cellulitis in children. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2006 Aug:25(8):695-9 [PubMed PMID: 16874168]

Lee S, Yen MT. Management of preseptal and orbital cellulitis. Saudi journal of ophthalmology : official journal of the Saudi Ophthalmological Society. 2011 Jan:25(1):21-9. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2010.10.004. Epub 2010 Dec 10 [PubMed PMID: 23960899]

Seltz LB, Smith J, Durairaj VD, Enzenauer R, Todd J. Microbiology and antibiotic management of orbital cellulitis. Pediatrics. 2011 Mar:127(3):e566-72. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2117. Epub 2011 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 21321025]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBedwell J, Bauman NM. Management of pediatric orbital cellulitis and abscess. Current opinion in otolaryngology & head and neck surgery. 2011 Dec:19(6):467-73. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e32834cd54a. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22001661]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRyan JT, Preciado DA, Bauman N, Pena M, Bose S, Zalzal GH, Choi S. Management of pediatric orbital cellulitis in patients with radiographic findings of subperiosteal abscess. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2009 Jun:140(6):907-11. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.02.014. Epub 2009 Apr 16 [PubMed PMID: 19467413]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence