Introduction

First described in 1888 by the German surgeon Franz König,[1] osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), also known as an osteochondral lesion, is not a fully understood process, though it is believed to be multi-factorial in etiology. OCD is an idiopathic process and can occur from childhood through adult life, with the majority of patients presenting in their teenage years. Osteochondral lesions range in severity from being asymptomatic to mild pain or advanced cases having symptoms of joint instability and locking. The lesions can progress from stable to fragmentation of the overlying cartilage with the formation of a loose body in the affected joint space. Eventual early-onset osteoarthritic changes of the joint can occur at any level of severity if not diagnosed and adequately managed; therefore, early recognition and treatment are important to achieve favorable long-term outcomes.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Although the etiology of osteochondritis dissecans is not fully elucidated, it is believed to be multi-factorial in nature. Postulated etiologies include genetic predisposition, inflammation, spontaneous avascular necrosis, and repetitive microtrauma. Originally believed to be related to osseous inflammation (hence the term osteochondritis), multiple studies have failed to prove inflammation as the underlying cause. The theory of spontaneous osteonecrosis is thought to occur during the maturation of the overlying cartilage during adolescence. At this time, the vascular supply to the subchondral bone transitions from a juvenile perichondrial supply to the mature supply from the medullary cavity. It is thought that during this transition period, the epiphyseal bone is predisposed to avascular necrosis. The higher prevalence of OCD in young athletes also suggests a repetitive microtrauma etiology. These theories have been studied with varying success in concluding the cause, but the most commonly accepted etiology is that of repetitive microtrauma, with or without an inciting event, that results in the patient’s initial presentation.[2][3]

Epidemiology

Osteochondritis dissecans occurs in approximately 15 to 29 per 100,000 patients.[4] Although it can occur from childhood through adult life, the majority of patients are 10 to 20 years of age.[5] Males are typically affected twice as often as females,[5] with a higher incidence occurring in young athletes. The knee, particularly the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle, is the most affected joint, with the elbow (capitellum) and ankle (talus) also affected to a lesser degree.[2],[6]

Pathophysiology

Regardless of etiology, osteochondritis dissecans is an idiopathic focal joint disorder affecting the subchondral bone. Fragmentation of a small focus of subchondral bone creates a defect between the osteochondral lesion and the parent bone, leading to decreased vascularization and resulting in osteonecrosis of the fragment. Stable fragments are those that are held in place by intact overlying articular cartilage. Progression of the defect to involve the overlying cartilage is possible, which leads to instability of the fragment. If lesions become unstable, they may remain in situ or displace from the parent site and become a loose body within the joint. Due to the altered articular surface caused by the osteochondral lesion, early-onset osteoarthritis occurs in a large percentage of these affected patients.

History and Physical

Presentation and discovery of osteochondral lesions are variable. Patients may be asymptomatic with incidental detection at imaging. This is true of patients who have always been asymptomatic or those who never presented for evaluation but can recall remote chronic mild pain that resolved without treatment. Other patients present during the phase of chronic mild pain of the affected joint, with or without an acute injury. These patients typically present several months to a year after the onset of symptoms. When the patient has a loose fragment, symptoms are generally more severe, with marked joint pain, locking, swelling, and joint instability.[3][2]

Upon physical exam, these patients may have tenderness with palpation, decreased or painful range of motion of the involved joint, and effusion or swelling. Other injuries, such as fracture and ligamentous injuries, should be excluded.[3]

Evaluation

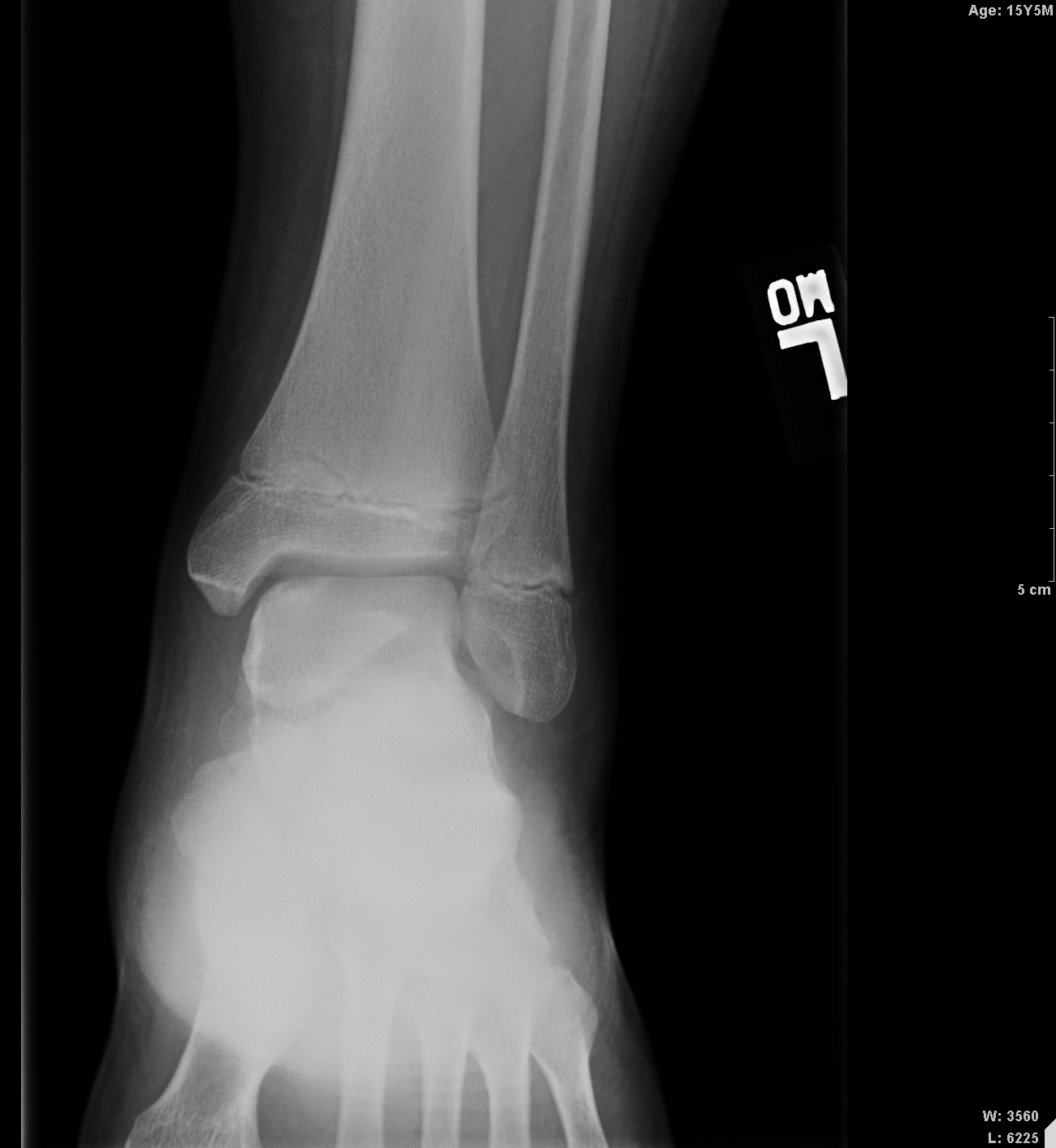

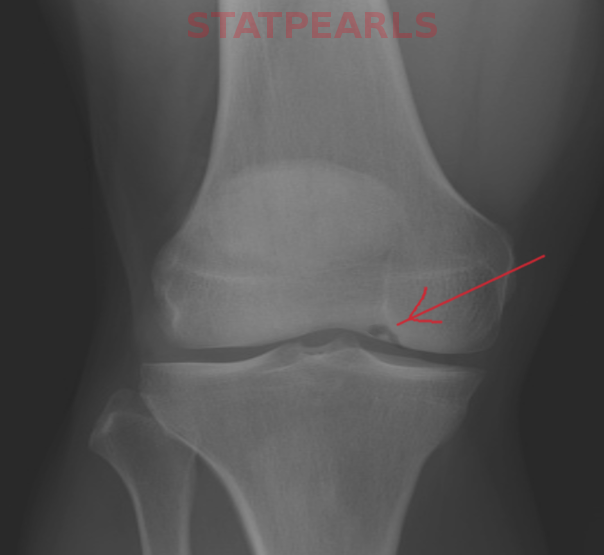

Imaging has a key role in the evaluation and management of these patients. Routine radiographs of the affected joint are the initial imaging obtained. Radiographs show an ovoid lucency affecting the subchondral bone with subjacent sclerotic bone. Occasionally the bony fragment may be visualized within the subchondral defect or, if displaced, elsewhere within the joint. Radiographs are unable to determine the stability of the osseous fragment and underestimate the lesion size. MRI is typically used to confirm the diagnosis when an abnormality is identified on radiographs in differentiating a developmental ossification variation from OCD and to aid in treatment planning, helping to determine if the lesion is likely to be stable at the time of arthroscopy. MRI is highly sensitive and specific in the evaluation of fragment stability; therefore, it is recommended for patients in whom stability is a clinical concern.

Initially described by De Smet in reference to the knee on T2 weighted images of the knee the following four signs on MRI are associated with OCD lesion instability[7]:

- Line of hyperintense signal equal to the fluid at the fragment bone interface measuring 5 mm or more in length,

- A discrete round focus of hyperintense signal deep to the OCD lesion measuring 5 mm or more,

- Focal defect in the overlying cartilage measuring 5 mm or more, and

- Hyperintense signal equal to the fluid that traverses the articular cartilage and the subchondral bone which extends to the lesion. These same findings can be applied to any joint with an OCD lesion to evaluate for stability. These criteria have high sensitivity and specificity in the determination of OCD lesion stability. MRI arthrography can be beneficial in difficult cases. CT arthrography, although not as sensitive, can be obtained in the patient when MRI is contraindicated.

MRI is also useful in the monitoring of treatment of these patients following diagnosis if conservative management or surgical treatment is chosen. The recommended time interval to perform MRI to evaluate healing is an institutional protocol and surgeon dependent. MRI findings that suggest healing following conservative management include: decrease or resolution in the surrounding bone marrow edema pattern, a decrease in lesion size, decrease or the resolution of the hyperintense T2 signal rim or cyst-like foci, and ingrowth of bone within the bed of the OCD lesion with osseous bridging. Following surgery, MRI allows for noninvasive evaluation of the repair of the articular surface and the bone cartilage interface.[7]

Treatment / Management

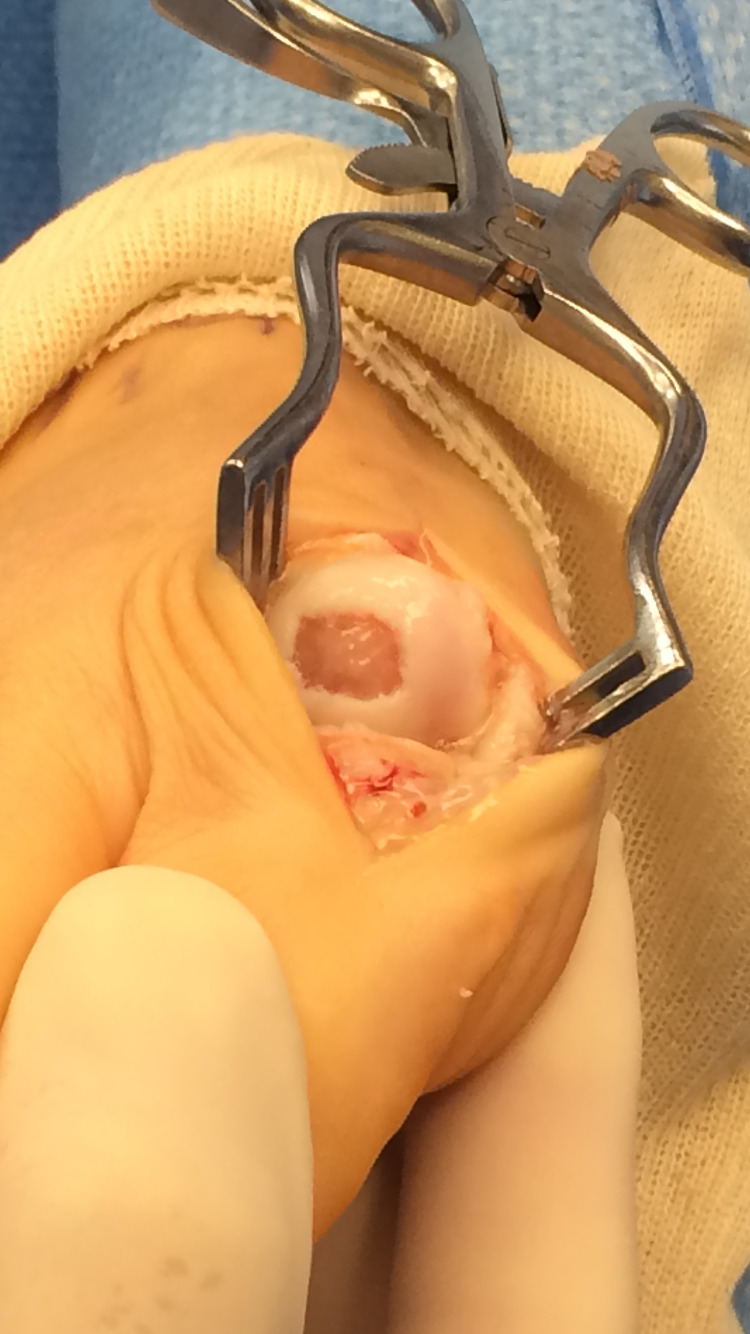

The patient’s age, time of presentation, severity of symptoms, and stability of the lesion will dictate treatment. Several systems to classify the lesions have been developed, with the important feature being the degree of overlying cartilage involvement and mobility of the lesion fragment. In stable lesions, conservative management is preferred with immobilization and protected weight-bearing for a length of time, depending on which joint is affected. Patients with stable lesions that fail conservative treatment may be treated with drilling techniques (retroarticular or transarticular drilling). These procedures have shown healing rates and symptom improvement ranging from 92% to 100%, with transarticular drilling having slightly higher success rates. When lesions are unstable or displaced, surgical intervention is necessary, typically performed arthroscopically. The knee is the location most often requiring surgery, with 58% of procedures for OCD lesions being performed on the knee. Various modalities and techniques exist, such as fixation, debridement, microfracture, and cartilage grafting/transplantation. In situ fixation of lesions can be performed using various types of metallic screws, bioabsorbable implants, or osteochondral plugs. Metallic fixation screws, when OCD lesion size permits their use, show high successful healing rates of 84% to 100%. The disadvantage of metallic screws is the need for a second procedure 6 to 12 weeks after initial fixation to remove the screw. Bioabsorbable implants do not require a second procedure for removal and show successful healing rates around 90%; however, these implants show higher rates of complications. Osteochondral autograft or allograft plugs can also be used, with clinical outcomes of “good to excellent” in 72% of patients receiving allograft plugs. The overall goal of surgery is the promotion of cartilage reformation and/or repair of the articular surface to prevent early-onset osteoarthritis.[8]

Differential Diagnosis

Osteoarthritis

Meniscus injury

Prognosis

Stable osteochondral lesions typically have a better outcome than unstable lesions. When stable lesions are treated with conservative treatment alone, spontaneous healing typically occurs. At present, there is no single uniform grading scale for lesions treated surgically. However, unstable lesions undergoing surgery, or those that fail conservative management and then undergo surgical treatment, tend to have a success rate of 30% to 100% depending on the technique utilized.[8] However, the large majority of patients treated surgically will still progress to develop early-onset osteoarthritis. Patients presenting for treatment during adolescence tend to have a better outcome than adult patients.

Complications

- Non-union

- Chronic pain

- Arthritis

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of osteochondritis dessecans is with an interprofessional team that consists of a radiologist, orthopedic surgeon, physical therapist, nurse practitioner, and primary caregiver. The patient’s age, time of presentation, the severity of symptoms, and stability of the lesion will dictate treatment. Several systems to classify the lesions have been developed, with the important feature being the degree of overlying cartilage involvement and mobility of the lesion fragment. In stable lesions, conservative management is preferred with immobilization and protected weight-bearing for a length of time, depending on which joint is affected. Patients with stable lesions that fail conservative treatment may be treated with drilling techniques (retroarticular or transarticular drilling). These procedures have shown healing rates and symptom improvement ranging from 92% to 100%, with transarticular drilling having slightly higher success rates. When lesions are unstable or displaced, surgical intervention is necessary, typically performed arthroscopically. In general, the outcomes of stable lesions are better than unstable lesions. [9][10](Level V)

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Kessler JI, Jacobs JC Jr, Cannamela PC, Shea KG, Weiss JM. Childhood Obesity is Associated With Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Knee, Ankle, and Elbow in Children and Adolescents. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. 2018 May/Jun:38(5):e296-e299. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001158. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29635262]

Edmonds EW, Polousky J. A review of knowledge in osteochondritis dissecans: 123 years of minimal evolution from König to the ROCK study group. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2013 Apr:471(4):1118-26. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2290-y. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22362466]

Zanon G, DI Vico G, Marullo M. Osteochondritis dissecans of the talus. Joints. 2014 Jul-Sep:2(3):115-23 [PubMed PMID: 25606554]

Andriolo L,Candrian C,Papio T,Cavicchioli A,Perdisa F,Filardo G, Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Knee - Conservative Treatment Strategies: A Systematic Review. Cartilage. 2018 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 29468901]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMichael JW, Wurth A, Eysel P, König DP. Long-term results after operative treatment of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee joint-30 year results. International orthopaedics. 2008 Apr:32(2):217-21. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0292-7. Epub 2007 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 18350293]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKubota M, Ishijima M, Ikeda H, Takazawa Y, Saita Y, Kaneko H, Kurosawa H, Kaneko K. Mid and long term outcomes after fixation of osteochondritis dissecans. Journal of orthopaedics. 2018 Jun:15(2):536-539. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2018.01.002. Epub 2018 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 29881188]

Zbojniewicz AM, Laor T. Imaging of osteochondritis dissecans. Clinics in sports medicine. 2014 Apr:33(2):221-50. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2013.12.002. Epub 2014 Feb 16 [PubMed PMID: 24698040]

Bauer KL,Polousky JD, Management of Osteochondritis Dissecans Lesions of the Knee, Elbow and Ankle. Clinics in sports medicine. 2017 Jul [PubMed PMID: 28577707]

Cheng C, Milewski MD, Nepple JJ, Reuman HS, Nissen CW. Predictive Role of Symptom Duration Before the Initial Clinical Presentation of Adolescents With Capitellar Osteochondritis Dissecans on Preoperative and Postoperative Measures: A Systematic Review. Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine. 2019 Feb:7(2):2325967118825059. doi: 10.1177/2325967118825059. Epub 2019 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 30800689]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYamagami N, Yamamoto S, Aoki A, Ito S, Uchio Y. Outcomes of surgical treatment for osteochondritis dissecans of the elbow: evaluation by lesion location. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2018 Dec:27(12):2262-2270. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2018.08.011. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30446232]