Introduction

The parotid gland is the largest of the 3 paired major salivary glands, including the submandibular and sublingual glands; this gland is located in the retromandibular fossa, a space mainly occupied by this gland and is bordered superiorly by the zygomatic arch, anteriorly by the masseter muscle, and posteriorly by the sternocleidomastoid muscle. However, the superficial lobe extends anteriorly, covering the mandibular ramus and the posterior area of the masseter muscle.[1] See Images. The Mouth, Right Parotid Gland, Posterior, and The Mouth, Right Parotid Gland, anterior. The parotid gland and the other salivary glands play an essential function in the oral cavity because they secret saliva, facilitating chewing, swallowing, speaking, and digesting.[2] The facial nerve courses through the body of the parotid gland, creating a unique relationship between them, which requires focused attention when performing parotidectomies or other surgery in the region.[3]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

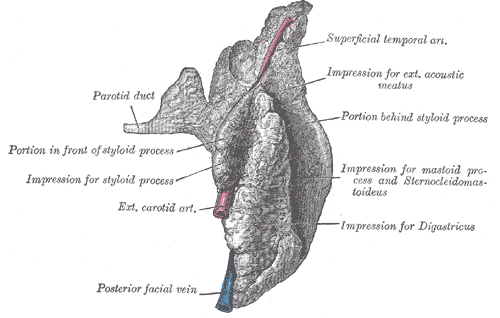

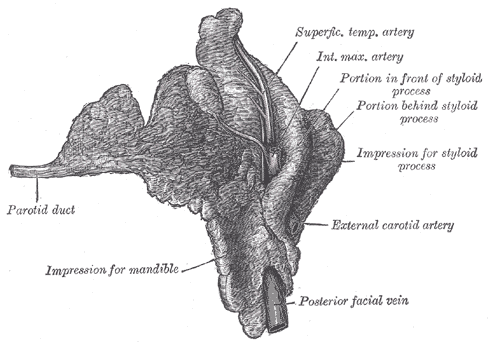

The parotid glands can be palpated anterior and inferior to the lower half of the ear on the lateral surface of the cheek. They extend inferiorly to the lower border of the mandible and superiorly to the zygomatic arch. Each parotid gland comprises a superficial lobe and a deep lobe divided by the facial nerve and the posterior facial vein. Between the lobes of the gland, there is also fatty tissue that facilitates mandibular movements. The superficial lobe lies lateral to the facial nerve and overlies the lateral surface of the masseter muscle. The deep lobe lies medial to the facial nerve and is situated between the mastoid process of the temporal bone and the mandibular ramus. A fascial capsule called the parotid sheath surrounds the parotid glands.[1]

The parotid main excretory duct (Stensen duct) projects from the anterior portion of the superficial lobe and runs over the masseter muscle until it reaches its anterior border, from where it turns medially to penetrate the buccinator muscle [1]. This opens into the buccal cavity at the level of the buccal mucosa of the maxillary second molar.[1] The salivary glands share the same histological structure—a secretory portion called acini and a web of arborized ducts that open into the buccal cavity realizing saliva.[2] The parotid is a serous gland composed mainly of serous acinar cells, but it may contain accessory glandular tissue formed by mucinous acinar cells. Therefore, saliva excreted by the parotid is serous and watery. Each serous acinus is surrounded by myoepithelial cells that contract to help expel secretions from the acini. Furthermore, an extracellular matrix, stromal cells, immune cells, myofibroblasts, and nerves are found in the periphery of the acini.[4] Saliva is first produced in the acinar lumen and then altered into a mixture of electrolytes and macromolecules as it is actively transported through the ducts. The saliva is hypotonic when it reaches the mouth, but salivary flow rates can influence the electrolyte composition. In addition to electrolytes, saliva also contains mucin and digestive enzymes. The most important enzyme is amylase, which initiates the digestion of carbohydrates.[2]

Embryology

The parotid gland starts developing in the 6th week of gestation [2] via a process of proliferation, budding length, and branching. The excretory ducts and acini derive from the ectoderm, whereas the gland's capsule and connective tissue come from the mesenchyme. The intimate relationship with the facial nerve is established from the beginning.[5]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Blood Supply

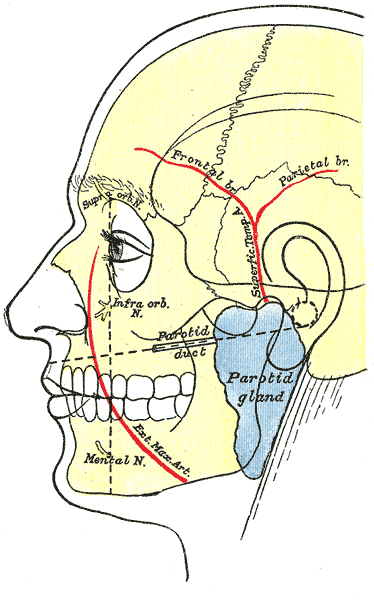

The external carotid artery provides blood supply to the parotid; this bifurcates into 2 terminal branches, the superficial temporal artery, and the maxillary artery (see Image. Surface Markings of Special Regions of the Head). The superficial temporal artery gives off the transverse facial artery, which runs anteriorly between the zygoma and parotid duct and supplies the parotid duct, parotid gland, and masseter muscle. The maxillary artery supplies the infratemporal fossa and the pterygopalatine fossa after exiting the medial portion of the parotid.[5] Finally, the retromandibular vein - which forms from the confluence of the superficial temporal and maxillary veins - provides venous outflow for the parotid. The blood supply courses deep into the facial nerve, and it may exhibit variable anatomy before joining the external jugular vein.[5]

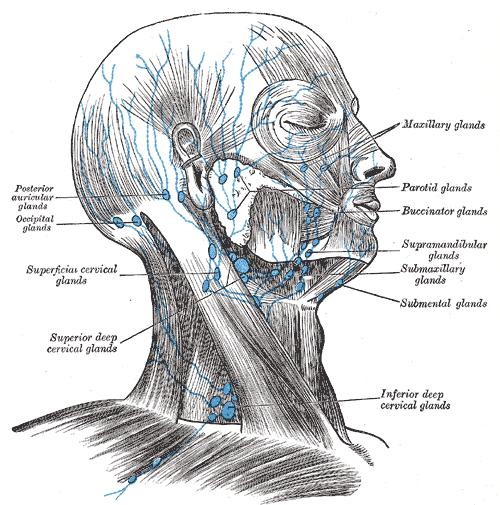

Lymphatics

The parotid gland is in intimate relation with the lymph nodes (see Image. Lymph Nodes of the Head and Neck). This is the only salivary gland with 2 nodal layers, which drain into the superficial and deep cervical lymph system. Most nodes are located within the superficial lobe between the gland and the parotid capsule.[2] Skin cancers of the face or scalp can enlarge the lymph nodes in the parotid gland, indicating the regional spread of carcinoma. Lymph nodes located in the parotid substance drain the gland, middle ear, nasopharynx, palate, and external meatus; the superficial preauricular lymph nodes drain the anterior pinna, temporal scalp, eyelids, and lacrimal glands.[5]

Nerves

Sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers innervate the parotid gland. Sympathetic innervation causes vasoconstriction, and parasympathetic innervation from the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX) produces the secretion of saliva.[5] The parasympathetic fibers originate in the inferior salivatory nucleus in the medulla and travel through the jugular foramen to the inferior ganglion. A small branch of the glossopharyngeal nerve called the tympanic or Jacobsen nerve, forms the tympanic plexus within the middle ear. These preganglionic fibers become the lesser petrosal nerve and course through the middle cranial fossa before exiting through the foramen ovale. They synapse in the otic ganglion, and the postganglionic parasympathetic fibers join the auriculotemporal nerve to innervate the parotid gland to secrete saliva.

The neurotransmitters acetylcholine (ACh) and norepinephrine (NE) act within the parotid. ACh binds muscarinic receptors to stimulate acinar activity and ductal transport; this also uses second messenger activity, producing inositol triphosphate, which increases calcium concentration within the cells. As a result, salivary secretion increases. Norepinephrine transmits sympathetic nervous impulses via postganglionic sympathetic fibers to the salivary glands—sympathetic outflow thickens saliva. NE binds beta-adrenergic receptors activating the adenylate cyclase second messenger system, producing cAMP, phosphorylating proteins, and activating enzymes. The facial nerve courses through the parotid gland, providing motor supply to the muscles of facial expression but does not provide innervation to the gland. The parotid gland is closely related to 2 muscles: sternocleidomastoid and masseter. The accessory nerve provides innervation to the sternocleidomastoid muscle,[6] which forms the posterior border of the retromandibular fossa. The superficial lobe of the parotid gland partly covers the mandibular ramus and the posterior part of the masseter muscle. The masseter muscle receives innervation by the masseteric nerve, a branch of the mandibular nerve.[7]

Surgical Considerations

The parotid gland is the location of 80% of salivary tumors.[5] The most common primary parotid tumor is pleomorphic adenoma (see Image. Parotid Mass). The management of neoplasias of the parotid typically includes surgical resection. Because the facial nerve courses through the glandular substance of the parotid gland, identifying this nerve is crucial when performing surgical procedures in the gland to prevent injuries. Some bony and soft tissue landmarks commonly used to identify the facial nerve trunk include the cartilaginous tragal pointer, the tympanomastoid suture, the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, the styloid process, and the retromandibular vein.[3] If an obstructing stone (sialolithiasis) causes refractory inflammation despite medical treatment, a procedure called sialoendoscopy can be performed for relief. It uses an endoscope to visualize the stone to aid the management.

Clinical Significance

Sialadenitis

- Sialadenitis is the inflammation of the salivary gland caused by obstruction and infection by bacteria, viruses, or stones.

- Signs and symptoms include pain, swelling of the gland, and fever.

- The most common microorganisms involved in the condition are staphylococcal bacteria and the mumps virus [8]

- Treatment includes antibiotics for bacterial infections, oral hydration, warm compresses, and drugs that induce salivary secretion. For cases of refractory infection, surgical management may be indicated (ie, abscess drainage)[9]

Sialolithiasis

- Sialolithiasis is a benign condition caused when a stone or calculus is lodged in a salivary duct. This is the most common cause of obstructive salivary gland disease and is responsible for half of all major salivary gland disorders [10]

- Signs and symptoms include pain and swelling in the affected duct, particularly during and after eating [11]

- Ultrasound imaging is the first step in the diagnosis. Computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and magnetic resonance sialography can be used in patients with a high suspicion of ductal obstruction who had a negative or inconclusive ultrasound study [10]

- The goal of treatment is to increase saliva flow through the duct with oral hydration and drugs that induce salivary secretion. Surgical removal of the calculus is required for chronic sialolithiasis that has failed conservative treatment [12]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Lymph Nodes of the Head and Neck. Illustration of the lymph nodes of the head and neck shows the posterior auricular glands, occipital glands, superficial cervical glands, superior deep cervical glands, inferior deep cervical glands, submental glands, submaxillary glands, supramandibular glands, buccinator glands, parotid glands, and maxillary glands.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Mouth, Right Parotid Gland, Posterior. Posterior and deep aspects, parotid duct, styloid process, exterior carotid artery, facial vein, and superficial temporal artery.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Mouth, Right Parotid Gland, Anterior. The right parotid gland, deep and anterior aspects.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Surface Markings of Special Regions of the Head. An outline of the side of the face showing chief surface markings, mental nerve, exterior maxillary artery, infra orbital nerve, parotid duct, and parotid gland.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Bialek EJ, Jakubowski W, Zajkowski P, Szopinski KT, Osmolski A. US of the major salivary glands: anatomy and spatial relationships, pathologic conditions, and pitfalls. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2006 May-Jun:26(3):745-63 [PubMed PMID: 16702452]

Ghannam MG, Singh P. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Salivary Glands. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30855909]

Borle RM, Jadhav A, Bhola N, Hingnikar P, Gaikwad P. Borle's triangle: A reliable anatomical landmark for ease of identification of facial nerve trunk during parotidectomy. Journal of oral biology and craniofacial research. 2019 Jan-Mar:9(1):33-36. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2018.08.004. Epub 2018 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 30191119]

Martinez-Madrigal F, Micheau C. Histology of the major salivary glands. The American journal of surgical pathology. 1989 Oct:13(10):879-99 [PubMed PMID: 2675654]

Carlson GW. The salivary glands. Embryology, anatomy, and surgical applications. The Surgical clinics of North America. 2000 Feb:80(1):261-73, xii [PubMed PMID: 10685152]

Abakay MA, Güneş S, Küçük C, Yazıcı ZM, Gülüstan F, Arslan MN, Sayın İ. Accessory Nerve Anatomy in Anterior and Posterior Cervical Triangle: A Fresh Cadaveric Study. Turkish archives of otorhinolaryngology. 2020 Sep:58(3):149-154. doi: 10.5152/tao.2020.5263. Epub 2020 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 33145498]

Procópio Pinheiro R, Gaubeur MA, Itezerote AM, Saleh SO, Hojaij F, Andrade M, Jacomo AL, Akamatsu FE. Anatomical Study of the Innervation of the Masseter Muscle and Its Correlation with Myofascial Trigger Points. Journal of pain research. 2020:13():3217-3226. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S265717. Epub 2020 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 33299345]

Armstrong MA, Turturro MA. Salivary gland emergencies. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2013 May:31(2):481-99. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2013.01.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23601484]

Plonowska KA, Gurman ZR, Humphrey A, Chang JL, Ryan WR. One-year outcomes of sialendoscopic-assisted salivary duct surgery for sialadenitis without sialolithiasis. The Laryngoscope. 2019 Apr:129(4):890-896. doi: 10.1002/lary.27433. Epub 2018 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 30152080]

Ugga L, Ravanelli M, Pallottino AA, Farina D, Maroldi R. Diagnostic work-up in obstructive and inflammatory salivary gland disorders. Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica : organo ufficiale della Societa italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale. 2017 Apr:37(2):83-93. doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-1597. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28516970]

Wilson KF, Meier JD, Ward PD. Salivary gland disorders. American family physician. 2014 Jun 1:89(11):882-8 [PubMed PMID: 25077394]

Luers JC, Grosheva M, Reifferscheid V, Stenner M, Beutner D. Sialendoscopy for sialolithiasis: early treatment, better outcome. Head & neck. 2012 Apr:34(4):499-504. doi: 10.1002/hed.21762. Epub 2011 Apr 11 [PubMed PMID: 21484927]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence