Introduction

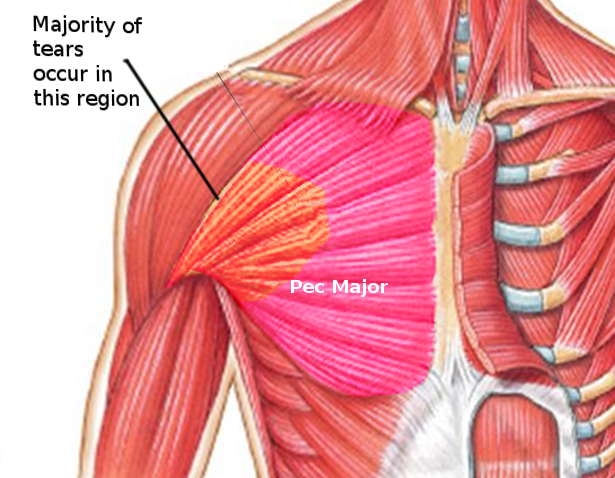

The pectoralis major is the superior most and largest muscle of the anterior chest wall. It is a thick, fan-shaped muscle that lies underneath the breast tissue and forms the anterior wall of the axilla. Its origin lies anterior surface of the medial half of the clavicle, the anterior surface of the sternum, the first 7 costal cartilages, the sternal end of the sixth rib, and the aponeurosis of the external oblique of the anterior abdominal wall. The insertion of the pectoralis major is at the lateral lip of the intertubercular sulcus of the humerus. There are 2 heads of the pectoralis major, the clavicular and the sternocostal, which reference their area of origin[1][2]. The sternocostal head is described as having between 2 to 7 distinct segments.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The function of the pectoralis major is 3-fold and dependent on which heads of muscles are involved.[1][2]

- Flexion, adduction and medial rotation of the arm at the glenohumeral joint

- Clavicular head causes flexion of the extended arm

- Sternoclavicular head causes extension of the flexed arm

The pectoralis major shows variation in muscle fiber length, differing from the majority of muscle fibers in the human body, which usually show uniform length. This configuration of the muscle fibers potentially allows for more power production through differing muscle shortening velocities.[1]

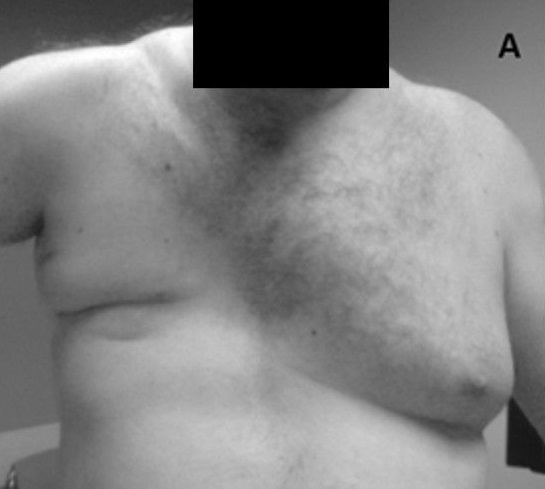

Embryology

Development of the skeletal muscles comes from the mesoderm, one of the 3 germ layers. In the fourth to eighth weeks, the paraxial mesoderm is organized alongside the neural tube in blocks of tissue called somites. The somites have 2 subpopulations of cells: the dorsolateral dermomyotome and the ventromedial sclerotome. The dermomyotome goes onto form the skeletal muscle. The sclerotome forms the axial skeleton at this level. Within the dermatomyotome, the anterior muscles of the embryo are formed from the hypomere cells.[3] Congenital abnormalities of the pectoral muscle can be seen in Poland syndrome.[4] This is characterized by the unilateral absence of the pectoralis major, usually occurring alongside ipsilateral symbrachydactyly and other malformations of the chest wall.[4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Arterial supply of the pectoralis major, the pectoral artery, arises from the second branch of the axillary artery, the thoracoacromial trunk. Its venous drainage is via the pectoral vein, draining into the subclavian vein.[1][2]

Nerves

The 2 heads of the pectoralis major have different nervous supplies. The clavicular head derives its nerve supply from the lateral pectoral nerve. The medial pectoral nerve innervates the sternocostal head. The lateral pectoral nerve arises directly from the lateral cord of the brachial plexus, and the medial pectoral nerve arises from the medial cord.[1][2] The lateral cord will travel anteriorly to the axillary artery and medial cord to the pectoralis minor. It then courses on the posterior surface of the pectoralis major and enters the muscle medial to the humeral insertion. The medial pectoral nerve arises posterior to the axillary artery, pierces the pectoralis minor near the midclavicular line, and inserts to the posterior surface of the pectoralis major in a number of branches.

Surgical Considerations

Given the pectoralis major's size, location, and blood supply it has been used in flap repairs in neck surgery. The muscle is highly vascularised via the thoracoacromial artery, so it has lower chances of necrosis in the flap formation.[5][6] Use of pectoralis major myocutaneous flaps (PMMC) is declining due to the development of vascularised free flaps. However, it is a reliable option for soft tissue reconstruction of the neck and face following trauma or tumor-related operations. The PMMC can be used to close head and neck defects, cover exposed vasculature, oropharyngeal, pharyngoesophageal, and skull base defects. The flap can also add bulk to radical neck dissection.[5]

Detailed knowledge of the anatomy of the pectoral muscle is necessary for breast surgery in particular. Modified radical mastectomy, breast reconstruction following mastectomy, and breast augmentation can pose risks to the nervous supply of the pectoralis major. Damage to the nerve can result in denervation and atrophy or fibrosis to a section of the pectoralis major. Pectoral nerve blocks are also more commonly used as postoperative analgesia.[7][8] It is believed to be less invasive and have fewer complications compared paravertebral or neuraxial blocks.

Clinical Significance

Pectoralis injury is relatively rare, 365 cases have been reported in the literature in a 2012 meta-analysis.[9] Tendon tears occurring almost exclusively in males between 20 and 40 years old, and around 50% of these are sustained during weight-bearing exercises such as the bench press when the arm under load is in extension and external rotation.[1] Examination of a pectoralis major rupture will see swelling, hematoma, medialization of the muscle bed, tenderness along the humeral insertion, and along the axilla.[1] These signs are not specific and may develop rapidly or over a period of weeks. Investigation of potential pectoral injury centers around clinical history and examination and radiology. Chest x-ray can rule out bony injury (avulsion occurring in 2% to 5% of cases), and ultrasound and MRI are well known to be able to diagnose and characterize tears.[1]

In 1980, Tietjen proposed a classification for pectoralis major injuries. Grading from I to III,[10]

- Grade I: Sprain or contusion

- Grade II: Partial tear

- Grade III: Complete tear: (a) sternoclavicular origin, (b) muscle belly, (c) musculotendinous junction, (d) insertion

The majority of tears are conservatively managed using analgesia, ice, and sling immobilization in the adducted and internally rotated position. The patient may gradually increase movement from 2 to 6 weeks. Light resistance activities can then be introduced from 6 to 8 weeks, and full return to resistance activity is possible at 3 to 5 months.[1] However, in cases of complete tears or in the young and athletic population, operative repair is advised and is ideally performed within 6 weeks of injury.[1] For the young and those involved in sports, surgical repair is the most appropriate way to regain the most strength, mobility, and function.

Other Issues

Summary of the Anatomy of the Pectoralis Major

- Origin: Clavicular head, anterior sternum, costal cartilages 1 to 7, the sternal end rib 6, aponeurosis of the external oblique

- Insertion: Lateral lip intertubercular sulcus of the humerus

- Nervous innervation: Medial and lateral pectoral nerves (clavicular head C5, sternocostal head C6/7/8, T1)

- Function: Flexion, adduction, and medial rotation of the arm at the glenohumeral joint; clavicular head causes flexion of the extended arm; sternoclavicular head causes extension of the flexed arm

- Arterial supply: Pectoral artery (thoracoacromial trunk, the second branch of the axillary artery)

- Venous drainage: Pectoral vein (drains into the subclavian vein)

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

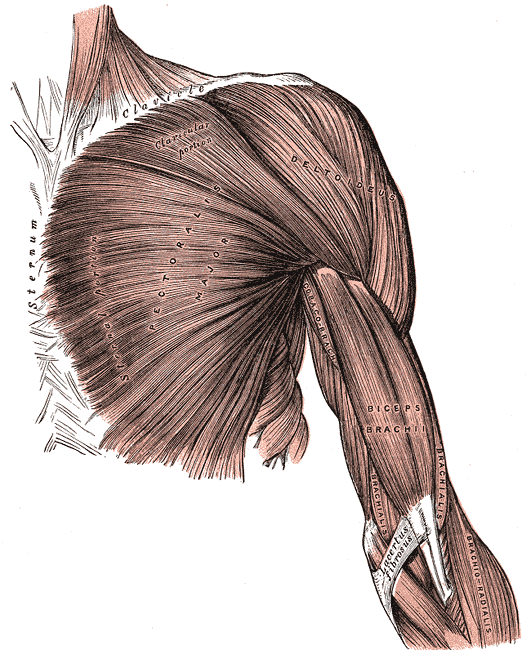

Superficial Muscles of the Chest and Shoulder. This illustration shows the pectoralis major, deltoid, coracobrachialis biceps brachii, brachialis, and brachioradialis. Other structures included in this image are the clavicle, sternum, and lacertus fibrosus.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

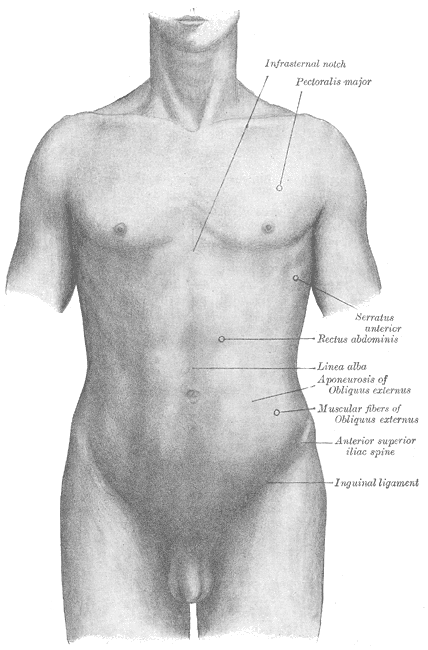

Surface anatomy of the front of the thorax and abdomen, Infrasternal notch, Pectoralis major, Serratus Anterior, Rectus abdominis, Linea alba, Aponeurosis of Obliques externus, Muscular Fibers of Obliques Externus, Anterior Superior iliac Spine, Inguinal ligament

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Poland Syndrome With Absence of Pectoralis Major Muscle

KJ Lizarraga and AAF De Salles, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Haley CA, Zacchilli MA. Pectoralis major injuries: evaluation and treatment. Clinics in sports medicine. 2014 Oct:33(4):739-56. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2014.06.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25280620]

Sanchez ER, Sanchez R, Moliver C. Anatomic relationship of the pectoralis major and minor muscles: a cadaveric study. Aesthetic surgery journal. 2014 Feb:34(2):258-63. doi: 10.1177/1090820X13519643. Epub 2014 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 24402060]

Warmbrunn MV, de Bakker BS, Hagoort J, Alefs-de Bakker PB, Oostra RJ. Hitherto unknown detailed muscle anatomy in an 8-week-old embryo. Journal of anatomy. 2018 Aug:233(2):243-254. doi: 10.1111/joa.12819. Epub 2018 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 29726018]

Yiyit N, Işıtmangil T, Öksüz S. Clinical analysis of 113 patients with Poland syndrome. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2015 Mar:99(3):999-1004. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.10.036. Epub 2015 Jan 27 [PubMed PMID: 25633462]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePatel K, Lyu DJ, Kademani D. Pectoralis major myocutaneous flap. Oral and maxillofacial surgery clinics of North America. 2014 Aug:26(3):421-6. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2014.05.010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25086697]

Bussu F, Gallus R, Navach V, Bruschini R, Tagliabue M, Almadori G, Paludetti G, Calabrese L. Contemporary role of pectoralis major regional flaps in head and neck surgery. Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica : organo ufficiale della Societa italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale. 2014 Oct:34(5):327-41 [PubMed PMID: 25709148]

Bashandy GM, Abbas DN. Pectoral nerves I and II blocks in multimodal analgesia for breast cancer surgery: a randomized clinical trial. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2015 Jan-Feb:40(1):68-74. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000163. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25376971]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMoon EJ, Kim SB, Chung JY, Song JY, Yi JW. Pectoral nerve block (Pecs block) with sedation for breast conserving surgery without general anesthesia. Annals of surgical treatment and research. 2017 Sep:93(3):166-169. doi: 10.4174/astr.2017.93.3.166. Epub 2017 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 28932733]

ElMaraghy AW, Devereaux MW. A systematic review and comprehensive classification of pectoralis major tears. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2012 Mar:21(3):412-22. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.04.035. Epub 2011 Aug 10 [PubMed PMID: 21831661]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTietjen R. Closed injuries of the pectoralis major muscle. The Journal of trauma. 1980 Mar:20(3):262-4 [PubMed PMID: 7359604]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence