Introduction

Pellegrini-Stieda lesions, named after early twentieth century Italian and German surgeons Augusto Pellegrini and Alfred Stieda, are defined as ossifications of the medial collateral ligament (MCL) at or near its proximal insertion on the medial femoral condyle.[1] While the eponym is credited to Pellegrini and Stieda, historically, the process was first described by Köhler in 1903, prior to the publications of its namesakes. Pellegrini-Stieda Disease (or syndrome) is defined as the combination of the aforementioned radiographic findings and concomitant medial knee joint pain or restricted range of motion.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of Pellegrini-Stieda is thought to be an insult to the medial collateral ligament causing damage and acute inflammation that sets into motion a process of delayed ossification. This insult has been classically described as a macrotrauma, whether direct or indirect, causing valgus stress with disruption of the MCL fibers. When initially described by Kohler in 1903 the ossification was particularly associated with sports activities. However, some reports from physiatrists have suggested micro-repetitive trauma from therapeutic manipulation of a restricted knee joint or post-surgical rehabilitation to be possible etiologies of Pellegrini-Stieda Disease with new-onset medial knee pain, edema, or restricted range-of-motion in an actively rehabilitating patient.[2][3] In some cases, Pellegrini-Stieda Disease has been seen in patients without knee trauma but concomitant spinal cord injury or traumatic brain injury. This calcific development, however, becomes difficult to discern from heterotopic ossification and myositis ossificans, the incidence of which increases in these patient populations.

Epidemiology

While the exact incidence is unknown, during a seven-year retrospective study of a clinical radiology database performed by a research team affiliated with The University of Colorado and The University of Alabama at Birmingham, knee radiograph reports of 332 patients included the term "Pellegrini Stieda."[4] The condition preferentially affects males, favoring patients between the ages of twenty-five and forty-years-old.[5]

Pathophysiology

The initial insult, whether resulting from macro- or repetitive microtrauma, leads to the same result: calcific ossification of the soft tissue structures surrounding the medial femoral condyle. In the cases associated with spinal cord injury or traumatic brain injury, neurogenic precipitation of ectopic bone formation can occur by humoral, neural, and local factors including tissue hypoxia, hypercalcemia, changes in sympathetic nerve activity, prolonged immobilization and subsequent mobilization.[6] Notably, the stereotypical localization of ossification of the medial collateral ligament has been questioned as studies have suggested that magnetic resonance imaging and anatomic cadaveric verification of suspected Pellegrini-Stieda lesions have demonstrated heterogeneous distribution inferiorly.[7][4] Mendes et al. went as far to suggest an alternative classification syndrome for Pellegrini Stieda lesions of Type 1 through Type 4 based on their location. Type 1 is referred to as a beak-like appearance and describes the ossification arising from the femur and extending inferiorly in the medial collateral ligament. Type 2 defines a tear-drop pattern, localized within the medial collateral ligament without any attachment to the femur. Type 3 presents as an elongated ossification superior to the femur lying in the distal adductor magnus tendon. Type 4 is also characterized as a beak-like appearance arising from the femur. However, this ossification extends into both the medial collateral ligament and adductor magnus tendon. Therefore, the original attribution of the syndrome to the medial collateral ligament may now be outdated as many publications have suggested concomitant and even sometimes preferential involvement of the adductor magnus tendon, medial head of the gastrocnemius, or medial patellofemoral ligament.[7][4] While most patients are asymptomatic from this ossification, a small percentage experience medial knee pain (with or without restricted knee range-of-motion and knee joint swelling) defined as Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome.

History and Physical

The following represents the typical presentation of Pellegrini Stieda Disease in a clinical setting: A thirty-year-old male presents to your clinic with a history of knee-to-knee collision to the medial right knee about three weeks ago during a recreational soccer game with acute pain that resolved after rest and ice. He now presents with new onset right medial knee pain and decreased range-of-motion of the right knee joint.

Evaluation

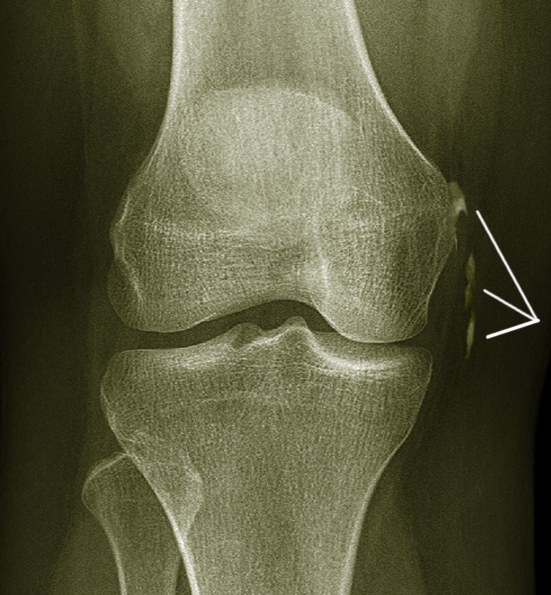

Diagnosis is typically made on plain radiographs demonstrating Pellegrini-Stieda sign accompanied by pain or restriction of range-of-motion of the knee joint. Pellegrini-Stieda sign is typically described by a longitudinally linear opacity, characteristic of calcification in the soft tissue located medial to the medial femoral condyle. This calcification seen on imaging represents the ossification of the medial collateral ligament, which typically does not develop until approximately three weeks after the initial injury.[8] It is essential to distinguish this radiographic finding from that of a medial femoral condyle avulsion fracture - an injury in which a pulling force of a tendon or ligament fractures away a piece of the bone from its attachment site. Similarly, on magnetic resonance imaging, bone marrow signal at the medial femoral condyle is accompanied by ossified characteristics, that of an enthesophyte, of the medial collateral ligament which appears thickened. The advent of musculoskeletal ultrasonography has also proven useful in diagnosing Pellegrini-Stieda lesions and can often elicit associated edema.

Treatment / Management

Symptom duration is typically five to six months as the ossified lesion matures. The severity of the pathology will dictate the treatment plan. Mild and moderate cases are usually managed conservatively with non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, corticosteroid injections, and range-of-motion exercises. Severe refractory cases, however, are considered candidates for surgical excision of medial collateral ligament calcifications. A study by Kulowski and Riebel showed a high variance in surgical outcomes, with a high recurrence rate, while data from Pellegrini and an updated Kulowski study showed quite the opposite. Additionally, surgical studies have warned that excision of larger lesions can lead to ligamentous defects requiring surgical reconstruction.[8](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

- Pellegrini-Stieda Disease

- Medial collateral ligament sprain

- Medial meniscal tear

- Medial femoral condyle avulsion fracture

- Myositis ossificans

- Heterotopic ossification

- Knee osteoarthritis

- Semimembranosus/semitendinosus tendinitis

Prognosis

While most cases of Pellegrini-Stieda Disease have documented symptom resolution within five to six months with conservative management of non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, corticosteroid injections, and range-of-motion exercises, some severe refractory cases require surgical intervention.

Complications

Untreated Pellegrini-Stieda Disease could lead to restricted knee joint range-of-motion and contracture developing into gait abnormalities, decreased activities of daily living, and chronic pain. Some studies have suggested poor surgical outcomes with high recurrence rates or ligamentous defects with large lesion excisions requiring further surgical reconstruction.[8]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Treatment for most patients is with a rehabilitative course consisting of range-of-motion and stretching exercises of the knee joint and medial collateral ligament. Therapists must tailor their therapy plan to avoid contracture caused by calcification of the medial collateral ligament.

Consultations

Initial consultation to a physical medicine and rehabilitation physician is optimal for guidance in directing an appropriate rehabilitation program. If the patient fails to achieve symptom resolution with conservative measures and a targeted rehabilitation program, one should consider orthopedic surgery evaluation for excision of the calcification.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be encouraged to continue stretching and range-of-motion exercises with a home exercise program following physical therapy treatment. The patient should be deterred from sedentary activities or prolonged joint immobilization. Reducing physical labor and exercise to light activity for pain avoidance is acceptable. However, full activity restriction is not the proper recommendation. There are no weight bearing precautions for this condition.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

interprofessional management of Pellegrini-Stieda disease is essential to diagnosis and treatment. While a patient may not present with symptoms of a Pellegrini-Stieda lesion, a radiographic examination may reveal the finding prior to the onset of symptoms beckoning Pellegrini-Stieda Disease. As such, communication between radiologists and orthopedic specialists is imperative. Similarly, many patients with knee pain may present initially to their primary care provider. Without a proper history and imaging, this condition may be mistaken for a medial collateral ligament sprain, knee osteoarthritis, medial meniscal tear or overuse injury of the semimembranosus/semitendinosus tendons. Once correctly diagnosed, the involvement of a physiatrist and rehabilitative team of physical therapists and orthopedic specialty nurses is crucial to improved prognosis, as conservative management with non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, corticosteroid injections, and range-of-motion exercises can limit the disease course to five-to-six months, with nursing serving as the bridge between PT and the clinicians. [Level V] Input from orthopedic surgeons for severe refractory cases is vital for determining surgical viability and managing patient expectations. The interprofessional approach as outlined above will yield optimal outcomes. [Level 5]

Media

References

Porro A, Lorusso L. Augusto Pellegrini (1877-1958): contributions to surgery and prosthetic orthopaedics. Journal of medical biography. 2007 May:15(2):68-74 [PubMed PMID: 17551603]

Yildiz N, Ardic F, Sabir N, Ercidogan O. Pellegrini-Stieda disease in traumatic brain injury rehabilitation. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation. 2008 Jun:87(6):514. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318174eb1b. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18496254]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAltschuler EL, Bryce TN. Images in clinical medicine. Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. 2006 Jan 5:354(1):e1 [PubMed PMID: 16394294]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcArthur TA,Pitt MJ,Garth WP Jr,Narducci CA Jr, Pellegrini-Stieda ossification can also involve the posterior attachment of the MPFL. Clinical imaging. 2016 Sep-Oct [PubMed PMID: 27348056]

Scheib JS, Quinet RJ. Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome mimicking acute septic arthritis. Southern medical journal. 1989 Jan:82(1):90-1 [PubMed PMID: 2911769]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceda Paz AC, Carod Artal FJ, Kalil RK. The function of proprioceptors in bone organization: a possible explanation for neurogenic heterotopic ossification in patients with neurological damage. Medical hypotheses. 2007:68(1):67-73 [PubMed PMID: 16919892]

Mendes LF, Pretterklieber ML, Cho JH, Garcia GM, Resnick DL, Chung CB. Pellegrini-Stieda disease: a heterogeneous disorder not synonymous with ossification/calcification of the tibial collateral ligament-anatomic and imaging investigation. Skeletal radiology. 2006 Dec:35(12):916-22 [PubMed PMID: 16988801]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTheivendran K,Lever CJ,Hart WJ, Good result after surgical treatment of Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA. 2009 Oct [PubMed PMID: 19221717]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence