Introduction

Pelvic floor prolapse is the herniation of the pelvic organs through the perineum. Depending on the pelvic organ involved, pelvic prolapse further categorizes into the anterior compartment containing urinary bladder(cystocele), the middle compartment containing uterine or vaginal prolapse (uterus or vagina), or the posterior compartment containing either the small bowel loops (enterocele) or rectum (rectocele). Pelvic prolapse is very common among multiparous women over 50, affecting approximately 50% of women over age 50.[1] The patients present with symptoms of stress fecal or urinary incontinence, uterine prolapse, constipation, or incomplete defecation. Besides, pelvic prolapse can negatively impact the patient's body image and sexuality. Pelvic prolapse treatments range from non-surgical approaches like Kegel exercise and pessary to various surgical procedures.[2] Treatments of pelvic prolapse significantly contribute to the healthcare cost in the United States, estimated at approximately $300 million from 2005 to 2006.[3]

Pelvic floor prolapse is most often clinically diagnosed through physical exams and medical history. Imaging plays a limited role in evaluating mild cases of pelvic prolapse that involve a single pelvic compartment and organ. Nonetheless, translabial ultrasound and dynamic pelvic MRI (MR defecography) serve as valuable tools in diagnosing pelvic prolapse in complex cases involving multiple compartments and multiple pelvic organs. Also, pelvic MRI provides pre-operative planning for complex cases. The article will discuss translabial ultrasound and dynamic pelvic MRI in the evaluation of pelvic prolapse.[4]

Anatomy

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy

The pelvic anatomy divides into three compartments: anterior, middle, and posterior. The anterior compartment contains the bladder and urethra. The vagina and uterus are within the middle compartment. Finally, the posterior compartment contains the sigmoid colon, rectum, and anal canal.[5]

The pelvic muscles, ligaments, and fascia prevent prolapse of the pelvic organs in each compartment. The most crucial pelvic fascia is endopelvic fascia, and it supports the uterus and vagina. Endopelvic fascia is composed of the uterosacral ligament, parametrium, and paracolpium. Pubocervical fascia is between the anterior vaginal wall and pubis; it supports the bladder. Lastly, the rectovaginal fascia supports the rectum. It situates between the posterior vaginal wall and rectum. The primary supporting pelvic muscles include iliococcygeal, pubococcygeal, and puborectal muscles. These are clearly visible on the pelvic MRI. On the other hand, the pelvic ligaments and fascia are less well appreciated on the MRI, but their dysfunctions can be inferred from the prolapse of pelvic organs in each compartment. In healthy patients, the pelvic muscles, ligaments, and fascia prevent the prolapse of pelvic organs and keep the rectum, vagina, and urethra elevated near the pubic symphysis.

Plain Films

Plain films are usually not appropriate for the evaluation of pelvic prolapse.[6] Barium defecography is in use at some places as a part of the assessment of pelvic floor dysfunctions, however, with the advent of newer and non-ionizing radiation imaging techniques like MR defecography, barium defecography has become largely obsolete.

Computed Tomography

Due to concern for radiation exposure and availability of MRI, which provides a better soft-tissue resolution, computed tomography (CT) is usually not appropriate for the evaluation of pelvic prolapse; however, one should look on sagittal abdomen and pelvis images for hint of pelvic floor prolapse by drawing a pubococcygeal line and see for overt prolapse and then recommend a dynamic MRI pelvis (MR Defecogram) for further evaluation.[6]

Magnetic Resonance

Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides an accurate assessment of pelvic prolapse. MRI provides a better anatomic detail compared to the translabial ultrasound and is also useful as a preoperative tool. Furthermore, the MRI examination does not require bowel preparation and does not involve sensitive pelvic exposure. Despite its benefits, the MRI is not widely available, expensive, and contraindicated in patients with MRI incompatible devices or hardware.

The patient lies supine in the MRI scanner. This examination utilizes a 1.5 or 3.0 Tesla magnet. Despite the fact pelvic prolapse is most prominent in the upright position, obtaining the images supine does not significantly compromise the diagnostic accuracy.[7] The study is performed following the administration of warm ultrasound gel per rectally, as this makes the rectal more prominent. The patient is encouraged to retain some urine in the urinary bladder as this will help diagnose cystocele. The duration of the scan is approximately 15 minutes. However, the length of the examination can be longer if additional images are necessary. Typical MRI protocol involves a large field of view in the sagittal plane and a small field of view in the axial plane. Images are obtained during the resting phase, the squeezing or kegel phase, with the Valsalva maneuver (straining phase) and defecation or evacuation phases. Coronal plane images are optional and usually not obtained.[7]

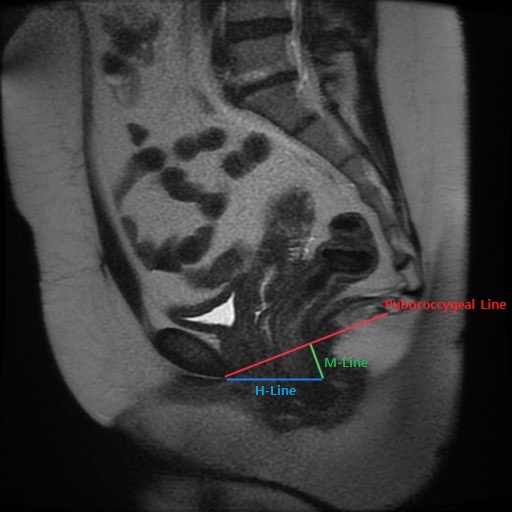

The interpretation of the images involves drawing the following lines: pubococcygeal line, M-Line, H-Line, and the anorectal angle.[8][9] Pubococcygeal line demarcates the level of the pelvic floor. The line is drawn between the inferior border of the pubic symphysis and the last intercoccygeal joint. Pelvic organ prolapse is subjectively assessed at rest, squeezing, or kegel phase, with the Valsalva maneuver, as well as the defecation phase. The degree of pelvic prolapse can be graded based on the depth of the descent below the pubococcygeal line as mild (less than 3 cm), moderate (3 to 6 cm), and severe (greater than 6 cm).[10] H- line defines the anterior-posterior width of the levator hiatus. The line is drawn between the inferior border of the pubic symphysis and the anterior wall of the rectum at the anorectal junction. The normal H- line should measure less than 5 cm. Finally, M-line measure the descendants of the levator hiatus. It is drawn perpendicular to the pubococcygeal line and intersects the inferior portion of the H-line. The normal M-line should measure less than 2 cm. H-line greater than 5 cm and M-line greater than 2 cm at rest or with the Valsalva indicates pelvic muscle weakness. The anorectal junction is an important landmark and helps in measuring the anorectal angle. The anorectal angle is the angle between the anal canal central axis and the posterior border of the distalmost portion of the rectum. The normal anorectal angle is between 108 and 127 degrees during the resting phase and denotes the functioning of the puborectalis muscle. Normally, the angle should open or become more obtuse with straining/Valsalva and defecation by approximately 20 degrees.[8][9] Chronic functional constipation is a significant symptom and can adversely affect one's social and personal life. The technical term for this is dyssynergic defecation or spastic pelvic floor syndrome. This condition characteristically presents by an inappropriate lack of relaxation of the puborectalis and external anal sphincter, leading to the urge of defecation without actual fecal emptying. Treatment includes biofeedback therapy, which uses psychophysiological tracings to improve physiological responses. Biofeedback therapy has proven to be very useful in these cases.

Ultrasonography

Translabial ultrasound is a relatively inexpensive way of evaluating pelvic prolapse and is widely available. Besides, the ultrasound does not produce ionizing radiation and allows dynamic evaluation of the pelvic floor. However, the diagnostic quality of the ultrasound exam depends on the sonographer’s skill level and interpreting radiologist familiarity with the examination. The examination also requires bowel preparation before the start of the exam due to fecal content in the rectum impairing the diagnostic accuracy. Furthermore, the translabial ultrasound is considered a sensitive exam involving genitalia and rectum. Despite the limitations of the exam, the translabial ultrasound is a widely available, safe, and inexpensive way of evaluating pelvic prolapse.

The patient is in the dorsal lithotomy position (hip flexed and abducted). The bladder must be empty before the examination. Using a curved 4 to 8 Mhz transducer, mid-sagittal images of the pelvis are obtained in both resting and with the Valsalva maneuver. Mid-sagittal images of the pelvic organ clearly demonstrate relations of the pelvic organs (bladder, vagina, uterus, and rectum) with the pelvic floor at the level of the pubic symphysis. The examiner can visualize and measure the degree of pelvic prolapse in real-time at rest and with the Valsalva maneuver. Furthermore, the bladder neck undergoes subjective and objective evaluation for hypermobility. Levator ani hiatal area is also calculated with the normal area being less than 25 mm^2. The degree of pelvic prolapse can be quantified based on the levator ani hiatal area as mild (25.0 to 29.9 mm^2), moderate (30.0 to 34.9 mm^2), marked (35.0 to 39.9 mm^2), or severe (greater than or equal to 40 mm^2).[10]

Nuclear Medicine

Nuclear medicine studies are usually not appropriate for the evaluation of pelvic prolapse.[6]

Angiography

Angiography is usually not appropriate for the evaluation of pelvic prolapse.[6]

Patient Positioning

As discussed above, the patient lies supine on the MRI examination. During the translabial ultrasound, the patient is in the dorsal lithotomy position (hip flexed and abducted).

Clinical Significance

Pelvic prolapse is a common condition affecting approximately 50% of parous women above 50.[1] The treatments for pelvic prolapse significantly contribute to the health care cost in the United States.[3] Pelvic prolapse is a clinical diagnosis. However, the dynamic MRI and translabial ultrasound are valuable tools for complicated multicompartment pelvic prolapse when the physical examination is often difficult.

Media

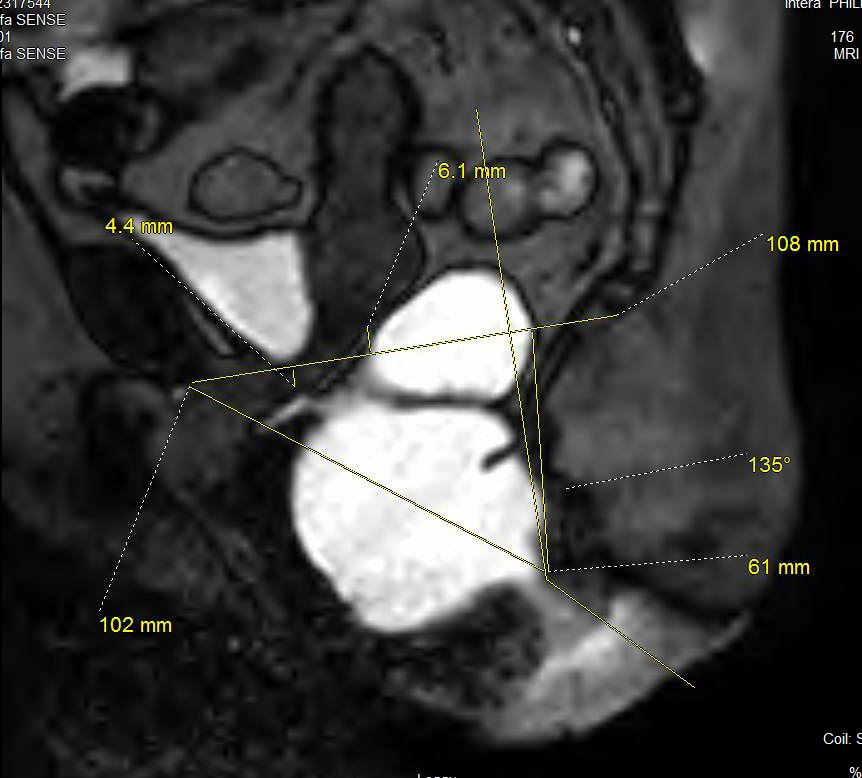

(Click Image to Enlarge)

This sagittal image from MR Defecography shows severe perineal descent syndrome involving the posterior compartment. Also note the moderate to severe anterior rectocele. No intrarectal intuscusseption or internal prolapse was seen. This image also demonstrates how all the measurements are performed. Contributed by Nishant Gupta, MD

References

Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Schmid C. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013 Apr 30:(4):CD004014. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004014.pub5. Epub 2013 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 23633316]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWoodley SJ, Boyle R, Cody JD, Mørkved S, Hay-Smith EJC. Pelvic floor muscle training for prevention and treatment of urinary and faecal incontinence in antenatal and postnatal women. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017 Dec 22:12(12):CD007471. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007471.pub3. Epub 2017 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 29271473]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSung VW, Washington B, Raker CA. Costs of ambulatory care related to female pelvic floor disorders in the United States. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2010 May:202(5):483.e1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.015. Epub 2010 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 20227673]

Baeßler K, Aigmüller T, Albrich S, Anthuber C, Finas D, Fink T, Fünfgeld C, Gabriel B, Henscher U, Hetzer FH, Hübner M, Junginger B, Jundt K, Kropshofer S, Kuhn A, Logé L, Nauman G, Peschers U, Pfiffer T, Schwandner O, Strauss A, Tunn R, Viereck V. Diagnosis and Therapy of Female Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Guideline of the DGGG, SGGG and OEGGG (S2e-Level, AWMF Registry Number 015/006, April 2016). Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde. 2016 Dec:76(12):1287-1301. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-119648. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28042167]

DeLancey JO. What's new in the functional anatomy of pelvic organ prolapse? Current opinion in obstetrics & gynecology. 2016 Oct:28(5):420-9. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000312. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27517338]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePannu HK, Javitt MC, Glanc P, Bhosale PR, Harisinghani MG, Khati NJ, Mitchell DG, Nyberg DA, Pandharipande PV, Shipp TD, Siegel CL, Simpson L, Wall DJ, Wong-You-Cheong JJ. ACR Appropriateness Criteria pelvic floor dysfunction. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR. 2015 Feb:12(2):134-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2014.10.021. Epub 2014 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 25652300]

Fielding JR. Practical MR imaging of female pelvic floor weakness. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2002 Mar-Apr:22(2):295-304 [PubMed PMID: 11896220]

Picchia S, Rengo M, Bellini D, Caruso D, Pironti E, Floris R, Laghi A. Dynamic MR of the pelvic floor: Influence of alternative methods to draw the pubococcygeal line (PCL) on the grading of pelvic floor descent. European journal of radiology open. 2019:6():187-191. doi: 10.1016/j.ejro.2019.05.002. Epub 2019 May 20 [PubMed PMID: 31193423]

Lakeman MM, Zijta FM, Peringa J, Nederveen AJ, Stoker J, Roovers JP. Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging to quantify pelvic organ prolapse: reliability of assessment and correlation with clinical findings and pelvic floor symptoms. International urogynecology journal. 2012 Nov:23(11):1547-54. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1772-5. Epub 2012 Apr 25 [PubMed PMID: 22531955]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChamié LP, Ribeiro DMFR, Caiado AHM, Warmbrand G, Serafini PC. Translabial US and Dynamic MR Imaging of the Pelvic Floor: Normal Anatomy and Dysfunction. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2018 Jan-Feb:38(1):287-308. doi: 10.1148/rg.2018170055. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29320316]