Introduction

Ultrasound (US) is the key modality for the evaluation of contents of the female pelvis. It allows ready (and portable) imaging of the uterus, ovaries, and other structures at a reasonable cost and without ionizing radiation. Lack of irradiation is important since the ovary is particularly sensitive to radiation in young patients and those of reproductive age. [1]

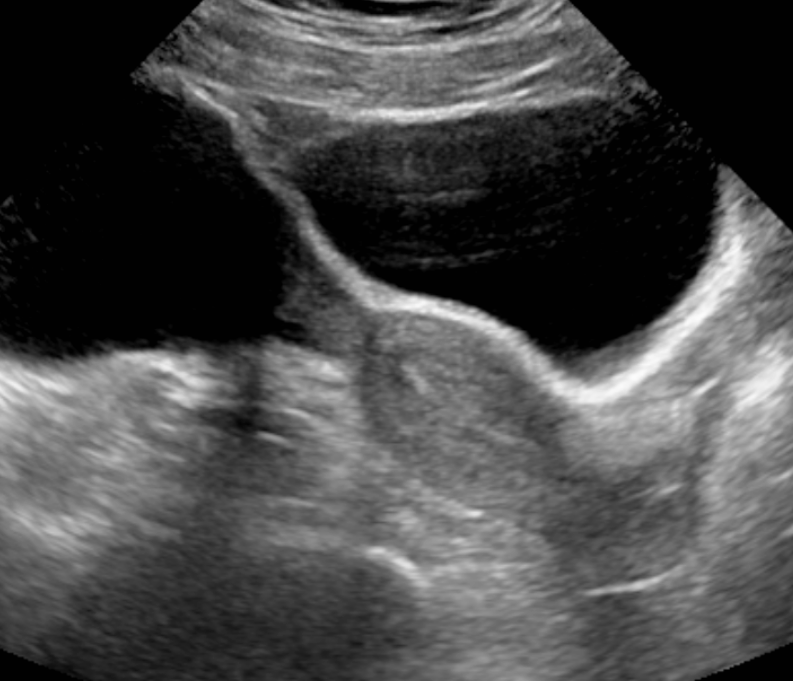

Pelvic US is performed either via the transabdominal (TA) or transvaginal (TV) approach. [2] Gel is placed on the skin above the bladder allowing transducer contact without intervening air on the skin surface. A urine-filled bladder helps lift small bowel superiorly, out of the pelvis creating an optimal acoustic window and preventing bowel air from refracting or degrading the ultrasound beam. [3] The US traverses the pelvis unimpeded through bladder fluid, insonating pelvic contents and returning to the transducer to be processed by the machine.

Images are obtained in the midline sagittal plane as well as parasagittal planes angled to the periphery of each hemipelvis. Similarly, transverse plane images are obtained by angling superiorly and inferiorly from a mid-bladder position. Real-time US allows the subtle angling of the transducer to obtain the best anatomic images even if the structures are not in perfect longitudinal or transverse plane alignment. [4] The uterus is typically located in the midline, and the ovaries and adnexa are usually found lateral to the uterus. However, just like a uterus may not be midline, the position of the ovaries is somewhat variable, possibly in the low, mid, or upper pelvis. They may also be seen in the midline, superior to the uterus.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Uterus/Cervix

The midline and parasagittal views are utilized to demonstrate the uterus from the fundus to cervix. The addition of transverse views allow for a complete assessment of size and contour, and the anatomy can be evaluated for abnormalities such as masses, typically benign leiomyomas. The uterine endometrial cavity may show contents of variable echogenicity if obstructed (e.g., from cervical stenosis in an older woman status post radiotherapy or a child with hematometrocolpos). Otherwise, the walls are coated, and the endometrial lining is visualized with a different echogenicity than the rest of the uterus often varied by hormone levels, patient age, and time in the menstrual cycle. [5] Classically the endometrial lining is echogenic with a trilaminar morphology in the first half of the menstrual cycle or proliferative phase. In the cycle’s second half (secretory phase) the lining is homogeneously echogenic. The thickness of the endometrial lining in a postmenopausal patient should measure no greater than 5 mm (unless treated with tamoxifen). Endometrial myomas or endometrial polyps or other masses may account for a prominent endometrial cavity, particularly in postmenopausal patients with unexplained bleeding. [6][7] US can help assess the endometrial contents via fluid injected thru the cervix, a methodology known as hysterosonography performed with transvaginal ultrasound.

Ovaries

The adnexa includes the ovaries, fallopian tubes, and their associated vasculature and soft tissue support structures. The ovaries appear almond shaped, typically lateral to the uterus and anterior to the internal iliac vasculature. Ovarian morphology, including the presence and number of contained follicles/cysts, vary with age, endocrine function, and time in the menstrual cycle. Knowledge of normal volumes for various ages are important when evaluating a patient for ovarian torsion. [8] Torsed ovaries can enlarge to 3 to 4 times normal ovarian volume. The contralateral ovary allows for size comparison. Pelvic inflammatory disease may enlarge both ovaries, but usually to a far less extent than the unilateral enlargement seen in ovarian torsion. Transvaginal US allows for better analysis of adnexal mass morphology by utilizing higher US frequencies.

Adnexa/Other Structures

Pelvic US can assess other structures within the pelvis. Hernias in the inguinal region or into the labia or canal of Nuck may be seen. Fallopian tubes may appear as dilated fluid-filled tubes (hydrosalpinx) due to obstruction, usually as a sequela of chronic infection. Unusually a fallopian tube may torse without concomitant ovarian torsion. Free fluid can also be demonstrated in the [abdomen and] pelvis. Triangular echoless areas particularly in the posterior cul de sac may be due to ascites or simply be physiologic fluid. Fluid with heterogeneous echogenicity or septation suggests a more complex component such as hemorrhage, infection, or proteinaceous fluid. Various other pathologies including appendicitis, diverticulitis, and gastrointestinal malignancy such as appendiceal mucoceles can also be visualized at times. [9]

Male Pelvis

Ultrasound use for the male pelvis is limited. The presence of free abdominal fluid can be assessed. Undescended testes in the groin and hernias can be seen using high-frequency linear array transducers. Magnetic resonance imaging is supplanting transrectal imaging for the evaluation of the prostate and seminal vesicles. TA US can allow visualization of the dilated urethra in posterior urethral valves, and occasionally a valve itself can be seen in real time. Inferiorly angled midline views are most helpful. The transperineal US can also be utilized for the diagnosis of posterior urethral valves.

Indications

These include:

- Examination of the normal pelvic contents including the uterus, ovaries, and adnexal structures.

- Masses palpated on physical examination can be further evaluated with US. Some commonly palpated masses include large ovarian tumors, congenital abnormalities of uterine shape (often noted in pregnancy), and uterine fibroids.

- Patients who present with pelvic pain can be evaluated by US. Often the diagnoses of pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian torsion, ectopic pregnancy, and normal pregnancy are made. Less often during pelvic US, appendicitis, inflammatory bowel disease, or diverticulitis is diagnosed.

- Abnormal vaginal bleeding can be related to possible pregnancy, known pregnancy, menses, precocious puberty, and postmenopausal bleeding.

- Evaluation for appropriate positioning of an intrauterine device. [10]

- Evaluation for polycystic ovarian syndrome and infertility. [11]

- US can be utilized for proof of ascites or other free fluid.

- In the male patient, pelvic US can evaluate the prostate and seminal vesicles. The prostate, particularly when looking for malignancy, is best assessed with a transrectal probe.

- US can be utilized for assistance in performing needle biopsies and aspiration of free fluid.

Contraindications

While there are no absolute contraindications to the usage of US, the use of TVUS may be relatively contraindicated in late pregnancy or in high-risk patients.

Equipment

US computer with transabdominal (TA) and transvaginal (TV) transducers that are of varying frequencies (MHz). Lower frequencies allow better penetration. Higher frequencies allow better near field resolution. TA probes are typically lower in frequency than TV probes.

Personnel

- Sonographer or sonologist.

- Interpreting physician.

Preparation

A urine-filled bladder is optimal for TA technique to view pelvic contents. No particular preparation is required for TV imaging.

Technique or Treatment

Transabdominal (TA)

The transabdominal technique usually consists of midline sagittal and parasagittal images angled from midline to the periphery of both hemipelves. Transverse plane images start at midline overlying the bladder and angle superiorly and inferiorly to image the pelvis. If there is limited fluid within the bladder, especially in young children, the transducer can be placed over the lateral aspect of the bladder and directed to the contralateral side for imaging. This helps provide a larger amount of fluid for the US beam to traverse and a better working acoustic window.

Transvaginal (TV)

TV scans use elongated transducers with higher frequency elements in the range of 7 MHz to 8 MHz, when compared to those used for routine TA imaging (near 3.5 MHz). The transducer is placed into the mid to upper vagina (covered by a condom) to obtain coronal and sagittal views that allow for high-resolution imaging of the uterus and its contents, helpful in obstetrical imaging as well as the analysis of the ovaries and adnexa. With its introduction in the late 1980s, TV US revolutionized the analysis for the presence or absence of ectopic pregnancy. The higher frequency TV transducer can be used because there is no need to traverse a fluid-filled bladder or anterior abdominal wall fat.

Other Techniques

Postprocessing software is available for many US machines, which allow three-dimensional reconstruction of typical greyscale ultrasound images to create a surface and volumetric images. This method has been used to reconstruct the vagina, cervix, and uterus for Mullerian Duct system anomalies.

At times the vagina and uterus may be evaluated by transperineal imaging, the placement of a transducer on the labia in the longitudinal or transverse plane. This has allowed analysis of vaginal obstructions, especially in virginal patients. It has been used for placenta previa analysis when the use of an intravaginal probe is deferred.

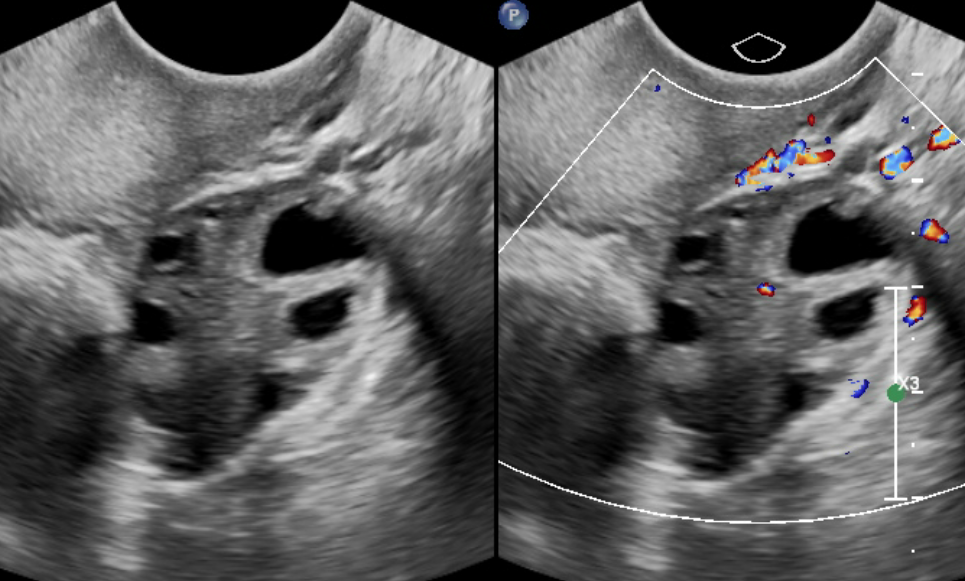

Doppler

Whether routine color Doppler or power Doppler imaging is used, cystic structures can be analyzed for their degree of vascularity. Color Doppler readily displays iliac vessel flow often in a plane posterior to the ovaries. Spectral Doppler can be utilized to evaluate vessels for abnormalities in venous or arterial flow signals. Pseudoaneurysms, although not typical in the pelvis when compared to the groin, might display the typical neck of the lesion with yin-yang color flow pattern. When evaluating for the presence or degree of vascular flow, power Doppler can also be utilized in situations for which color Doppler may be suboptimal (very low or slow flow).

Color Doppler can reveal dilated or clotted gonadal veins. It can also be used to demonstrate vascular flow to the ovary. However, due to the dual blood supply of the ovary, and the known findings of peripheral and central vascular flow in surgically proven torsed ovaries, the usefulness of color Doppler is limited. The greyscale morphologic findings of the ovary for the diagnosis of torsion are more sensitive than the flow-related findings seen with color Doppler. For the evaluation of testicular torsion, color Doppler is diagnostic.

Clinical Significance

Much information of clinical significance is discovered when imaging the pelvis with ultrasound. This includes information about the uterus, its shape, size, and characteristics of endometrial cavity and its contents. Identification and evaluation of ovarian size and morphology help determine if there are any abnormalities in the ovary for a given age. US can identify masses in structures other than the uterus and ovaries such as adnexal cysts. Ovarian neoplasms can be assessed for size and morphology and growth over time. This may include ovarian teratomas with their usual cystic and solid (Rokitansky nodule) contents including bone or calcium. Rectal contents can be evaluated, especially in neonates or young children. Thick bowel walls of chronic inflammation or tumor may be noted at times. Urethral cysts may be seen, particularly in adult females. Rarely an abnormality of the bony pelvis may be noted.[12][13][14]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A pelvic ultrasound is the ideal imaging technique in pregnant women as it does not entail use of contrast or x-rays. The technique can be done at the bedside and is cost effective.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Ogilvy-Stuart AL,Shalet SM, Effect of radiation on the human reproductive system. Environmental health perspectives. 1993 Jul [PubMed PMID: 8243379]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKurzweil A,Martin J, Transabdominal Ultrasound . 2020 Jan [PubMed PMID: 30521234]

Carovac A,Smajlovic F,Junuzovic D, Application of ultrasound in medicine. Acta informatica medica : AIM : journal of the Society for Medical Informatics of Bosnia & Herzegovina : casopis Drustva za medicinsku informatiku BiH. 2011 Sep [PubMed PMID: 23408755]

[Guidelines to income tax returns and deductions]., Kisling P,, Sygeplejersken, 1979 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 28790701]

AIUM practice guideline for the performance of ultrasound of the female pelvis.,, Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, 2014 Jun [PubMed PMID: 24866623]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSaline infusion sonohysterography: technique, indications, and imaging findings., Berridge DL,Winter TC,, Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, 2004 Jan [PubMed PMID: 14756358]

Sonohysterography., O'Neill MJ,, Radiologic clinics of North America, 2003 Jul [PubMed PMID: 12899492]

[Will anybody take over the Danish Nursing Council's stepchildren?]., Sløk B,, Sygeplejersken, 1979 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 28974907]

[Nationwide professional federation: possibilities of a change to new bylaws or retaining the current ones]., Andersen I,, Sygeplejersken, 1979 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 22634768]

Nowitzki KM,Hoimes ML,Chen B,Zheng LZ,Kim YH, Ultrasonography of intrauterine devices. Ultrasonography (Seoul, Korea). 2015 Jul [PubMed PMID: 25985959]

Catteau-Jonard S,Bancquart J,Poncelet E,Lefebvre-Maunoury C,Robin G,Dewailly D, Polycystic ovaries at ultrasound: normal variant or silent polycystic ovary syndrome? Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology : the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2012 Aug [PubMed PMID: 22648908]

Taithongchai A,Sultan AH,Wieczorek PA,Thakar R, Clinical application of 2D and 3D pelvic floor ultrasound of mid-urethral slings and vaginal wall mesh. International urogynecology journal. 2019 May 11; [PubMed PMID: 31079196]

Gillor M,Dietz HP, Translabial ultrasound imaging of urethral diverticula. Ultrasound in obstetrics [PubMed PMID: 31038237]

Vagholkar K,Vagholkar S, Abdominal Wall Endometrioma: A Diagnostic Enigma-A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case reports in obstetrics and gynecology. 2019; [PubMed PMID: 31032131]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence