Introduction

Constrictive pericarditis is a disease involving scarring and loss of elasticity of the pericardium surrounding the heart, leading to impaired filling. Effusive-constrictive pericarditis (ECP) is a less common syndrome involving both constriction of the visceral pericardium and an effusion causing a tamponade-like effect on the heart. The etiology is similar to constrictive pericarditis, including cardiac surgery and tuberculosis in the developing world. The symptoms of this syndrome mimic those of heart failure (particularly right-sided heart failure symptoms) and volume overload. This condition is chronic, and treatment is mostly surgical, although, in a subset of patients, treatment of the underlying cause may reverse both the effusion and the constriction. Most cases are idiopathic in terms of etiology. This article reviews this increasingly recognized variant, effusive-constrictive pericarditis, including its diagnosis and management.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The pericardium is composed of two layers: a visceral layer and a parietal layer. These two layers are naturally separated by a small amount (up to 50 mL) of fluid, which provides lubrication, reducing friction on the epicardium of the heart while equalizing forces over the surface of the heart to buffer increased variation in transmural cardiac pressures. Additionally, it permits transmission of intrathoracic pressure changes to the heart. Any supraphysiologic collection of fluid between these two layers is described as an effusion. These effusions may be transudative, exudative, sanguineous, or chylous. Inflammation of the pericardium secondary to any number of diseases leads to scarring and fibrosis, which eventually causes loss of elasticity of the pericardium. This fibrosis prevents expansion of the pericardium, leading to external compression of the heart and impeded filling.

Causes of effusion and constriction overlap. In the developed world, causes include idiopathic, viral, post-procedural, radiation, drug-induced, connective tissue disease, post-myocardial infarction (Dressler syndrome), malignancy, trauma, and uremia. In the developing world, the most common cause is tuberculous pericarditis. Specifically, in regions where tuberculosis is common, tuberculosis is a frequent cause of effusive-constrictive pericarditis. In one study, patients most likely to develop constrictive pericarditis after an episode of acute pericarditis had a fever, a chronic course of pericarditis, nonviral/nonidiopathic etiology, a large pericardial effusion, tamponade, use of steroids, or failure to respond to NSAID therapy.[2][3][4][5]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of effusive-constrictive pericarditis ranges from 2.4% to 14.8% in the literature, although this is probably underestimated due to the lack of definitive diagnostic studies done to confirm the presence of both constriction and effusion. In a study of 1184 patients with pericarditis and 218 patients with tamponade, 15 patients had concomitant effusive-constrictive pericarditis. In patients with tuberculous pericarditis, about 3% to 14% have effusive-constrictive pericarditis. In multiple large series of patients with constrictive pericarditis, idiopathic/viral comprised 42% to 49% of cases, cardiac surgery comprised 11% to 37% of cases, radiation therapy accounted for 9% to 31% of cases, connective tissue disorders, 3% to 7% of cases, and tuberculosis/infectious, 3% to 6% of cases. In a study of 500 cases with a first episode of acute pericarditis, the incidence rate of constrictive pericarditis was 0.76 cases per 1000 person-years for viral/idiopathic pericarditis, 4.40 cases per 1000 person-years for connective tissue disease/pericardial injury syndrome, 6.33 cases per 1000 person-years for malignant pericarditis, 31.65 cases per 1000 person-years for tuberculous pericarditis, and 52.74 cases per 1000 person-years for purulent/infectious pericarditis.[6][7]

Pathophysiology

In the process of healing, the initial episode of acute pericarditis, obliteration of the pericardial cavity occurs by granulation tissue formation and subsequent fibrosis of the pericardium. This causes the heart to be encased in a contracted, non-elastic pericardium. This rigid pericardium prevents transmission of negative intrathoracic pressures during inspirations to the heart, limiting ventricular filling during late diastole when the pericardium has reached its elastic limit. In the case of a concomitant effusion, the ventricular filling is impeded during the entire diastolic cycle due to tamponading of the heart. In all, both disorders lead to decreased end-diastolic volume and, therefore, decreased cardiac output. In constrictive pericarditis, the dissociation between intrathoracic pressure and intracardiac pressures due to decreased pericardial elasticity decreases venous return with inspiration. However, stretching of pulmonary veins during inspiration still occurs, whereas left ventricular pressure remains constant, causing decreased left ventricular filling.

This decrease in left ventricular (LV) volume allows a septal shift to the left, permitting filling of the right ventricle (RV) but not due to increases in venous return. In tamponade, there still is a transmission of intrathoracic pressures to the heart, causing increased venous return during inspiration. This causes bowing of the interventricular septum into the LV during diastole, preventing complete filling of the left side of the heart. This is coupled with decreased LV return due to low pulmonary venous pressure compared to left ventricular pressure. Common to both disorders is the equalization of the diastolic pressures in all four chambers. This occurs due to a fixed pericardium or fluid volume exerting equal contact pressures on all chambers, causing elevation and equalization of the diastolic pressures. Additionally, the stiff pericardium limits the expansion of the ventricles beyond a point after which one can fill only by compression of the other. In tamponade, these pressures decrease in unison during inspiration, whereas in pericarditis, right atrial pressure may increase or remain constant during inspiration while left atrial/pulmonary capillary wedge pressure decreases. In patients with effusive-constrictive pericarditis, a pericardial effusion under compression of a fixed pericardium mimics tamponade.[8][2]

Histopathology

Pericardial reaction to injury involves the release of serous fluid, fibrin, cells, or a combination determined by the underlying cause. Infectious injury to the pericardium causes two different types of reactions. Viral injury produces a transient pericardial reaction, which mostly resolves. Acid-fast organisms such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis cause a mononuclear reaction, eventually resulting in severe fibrous thickening of the pericardium. Pyogenic organisms cause a polymorphonuclear reaction that may also progress to fibrous thickening and constriction.

Histopathologic examination of the constricted pericardium will show fibrotic thickening, fibrin deposition with organization, and non-specific inflammation. A proliferation of the pericardial mesothelial cells occurs with thickening. The effusions themselves may be serous (seen in congestive heart failure, hypoalbuminemia, viral and irradiation), sanguineous or bloody (seen in acute myocardial infarction, aortic rupture or dissection, cardiac surgery, anticoagulation, chronic renal disease, and malignancy), chylous (seen with injury to the thoracic duct), or purulent (seen in infectious etiologies). Finally, adhesions may occur between the two pericardial layers, causing obliteration of the potential space. This occurs with healing after serosal injury, radiation, infectious agents, idiopathy, and connective tissue disorders.[3]

History and Physical

In effusive-constrictive pericarditis, patients commonly present with chronic symptoms that mimic volume overload. These include jugular venous distension, ascites, hepatomegaly, peripheral edema, and pleural effusions. Tachycardia occurs reflexively due to decreased cardiac output. Other signs and symptoms of decreased cardiac output include increased fatigue, hypotension, altered mental status, dyspnea, and tachypnea. Signs of active pericarditis may also ensue, including fever, pleuritic substernal chest pain, and a pericardial friction rub. Jugular venous distention also occurs due to decreased right heart filling and subsequent backup into the venous system.

There may be a few signs to distinguish effusive-constrictive pericarditis from chronic pericarditis alone. Pulsus paradoxus is a drop in blood pressure by greater than 10 mmHg during inspiration. This phenomenon occurs in cardiac tamponade due to compression of the left ventricle by the deviated septum during right ventricular filling secondary to chamber interdependence in limited pericardial space. Under a tense pericardium, an effusion that may have otherwise been unnoticeable mimics signs of tamponade in effusive-constrictive pericarditis. A third heart sound known as a pericardial knock may be more noticeable and found more often in patients with effusive-constrictive pericarditis with dominating constrictive features. This sound is due to the sudden deceleration of ventricular filling as the pericardium reaches its elastic limits. Kussmaul sign, a rise in right atrial pressure during inspiration, occurs in effusive-constrictive pericarditis with predominating constrictive features due to dissociation of the intrathoracic and intracardiac pressures, causing constant or elevated RA pressure throughout diastole. In tamponade, this occurs less often as intrathoracic pressures are still transmitted to the heart, preserving inspiratory increase in systemic venous return and decreasing right-sided backup.[9][10]

Evaluation

Echocardiography is recommended to evaluate constrictive pericarditis as it has excellent sensitivity and specificity for detecting effusions. This is observed as echolucent free space between the visceral and parietal pericardium. Echocardiography also permits the estimation of effusion size. Constrictive pericarditis on echocardiography may show increased pericardial thickness with or without calcification. A rapid deceleration during diastolic filling, as the ventricular volume approximates that of the constraining pericardium, along with deviation of the septum toward the left ventricle (septal bounce) are specific and sensitive signs of constriction and ventricular interdependence seen on echocardiography, respectively. Doppler recordings will also show abnormal filling in early diastole, increased transtricuspid diastolic flow velocity during inspiration, decrease during expiration, and a reduction in transmitral flow during inspiration. M mode is essential in ruling out constrictive pericarditis, and the absence of the following makes the diagnosis unlikely: the posterior motion of the septum during early diastole on inspiration, lack of increase in venous return during inspiration, and early pulmonic valve opening secondary to higher right-sided pressure compared to pulmonary artery pressure.

The hallmark of effusive-constrictive pericarditis is the persistence of elevated right atrial pressure after removal of the pericardial fluid. Cardiac catheterization will show elevated and equalized pressures in all four chambers prior to pericardiocentesis, along with a reduction in cardiac output and pulsus paradoxus. In constrictive pericarditis without effusion, atrial catheterization shows a prominent X descent, caused by elevated right atrial pressures during atrial repolarization, and prominent Y descent, caused by rapid atrial emptying with increased early diastolic filling. In ventricular pressure tracings, there is also what is called the “square root sign” or “dip and plateau pattern” caused by rapid early diastolic filling, followed by the abrupt halting of filling, as the stiff pericardium limit impedes ventricular expansion. This causes a dip (early diastolic filling) followed by a rapid rise and plateau (square root sign) in ventricular pressures. In tamponade, the Y descent is blunted due to decreased holodiastolic filling of the ventricle. In patients with effusive-constrictive pericarditis, right atrial pressure waves are intermediate. Before pericardiocentesis, there is a prominent X and blunted Y. Lack of hemodynamic normalization after pericardiocentesis, along with the prominent X and Y waves, along with the “dip and plateau” patterns of constrictive pericarditis, confirm the diagnosis of effusive-constrictive pericarditis.

Chest radiography is not sensitive in diagnosing effusive constrictive pericarditis, although the cardiac silhouette may appear enlarged if the effusion is large enough. The cardiac silhouette may also be flask-shaped, without evidence of pulmonary congestion, as this is not a left-sided failure in origin. However, the absence of evidence of chest radiography does not rule out effusive-constrictive pericarditis.

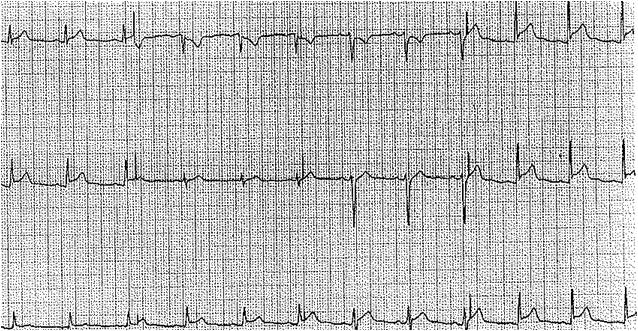

An electrocardiogram may show low amplitude in all leads due to an effusion-blunting electrical activity to the chest wall. There may also be nonspecific ST-T wave changes if acute pericarditis is ongoing. In the presence of a large effusion, electrical alternans occurs due to the rocking motion of the heart in the effusion during the respiratory cycle and is evident as alternating amplitudes of the QRS waves.[8][11][12]

Treatment / Management

Therapeutic management of effusive-constrictive pericarditis is both symptomatic and curative. The treatment should be guided to the underlying cause if it was determined. Symptomatically, patients may be treated with NSAIDs, colchicine, or steroids for the pain and inflammation. Caution must be taken with steroids as this may actually cause clinical deterioration in some patients. Diuretics may be used to relieve symptoms of volume overload but must be applied cautiously as there is already decreased cardiac output seen in these patients. Treatment of the underlying disorder (e.g., uremia, infection, etc..) is also necessary for decreasing the inflammatory cycle. Pericardiocentesis could be required to relieve cardiac compression. Despite these temporizing measures, the underlying constricted pericardium will continue to cause symptoms unless surgically removed. As such, pericardiectomy is the only definitive management of effusive-constrictive pericarditis and requires removal of both the visceral and parietal pericardium, which is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Although curative, every procedure has associated risks, so it should be reserved for patients not responding to medical management. A subset of patients may have a spontaneous resolution after treatment of the underlying disorder or whose symptom severity responds to anti-inflammatory agents. Surgery should be postponed in such patients.[13][14][15](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of effusive-constrictive pericarditis includes causes of cardiac tamponade alone without constriction, including but not limited to aortic rupture or dissection, myocardial infarction, malignancy, radiation, immunocompromised states, connective tissue disease, uremia, infiltrative disorders, tuberculosis, simple effusion, and acute pericarditis. Constrictive pericarditis alone may also mimic effusive-constrictive pericarditis, along with conditions presenting similarly to constrictive pericarditis, including restrictive cardiomyopathy, amyloidosis, hemochromatosis, and other infiltrative disorders. Symptomatically, tricuspid regurgitation, and other causes of right heart failure mimic the decreased systemic venous return and overload seen in this condition.

Prognosis

The outcome of effusive-constrictive pericarditis without treatment is dismal. In a systematic review of all causes of effusive-constrictive pericarditis in the literature, the pericardiectomy rate ranged from 40% to 100%, and the mortality rate was as high as 50% overall. In addition to the syndrome itself and post-operative complications, patients may die from the underlying disorder, including metastases or tuberculosis. The perioperative mortality of pericardiectomy is high. After pericardiectomy, the mortality rate was as high as 50% if a bypass was required in one institution's experience. However, in patients not requiring a bypass, the mortality rate was 0%. The risk of overall mortality is also increased with the degree of heart failure, radiation, post-cardiac surgery, and the need for cardiopulmonary bypass.[14][16]

Complications

Left untreated, effusive pericarditis can result in life-threatening sequelae, most notably heart failure symptoms. But with proper treatment and management, many patients with this condition can live healthy lives.

Deterrence and Patient Education

While effusive pericarditis generally presents with non-specific symptoms, patients need to understand the importance of reporting any worsening dyspnea, peripheral edema, loss or gain of weight, and pressure or pain in their chest.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effusive constrictive pericarditis is best managed by an interprofessional team that also includes cardiac nurse practitioners. While aspiration may temporarily relieve symptoms, the definitive treatment is pericardiectomy. However, before surgery is undertaken, the patient's medical condition must be optimized. Following pericardiectomy, most patients are relieved of symptoms.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Acharya A, Koirala R, Rajbhandari N, Sharma J, Rajbanshi B. Anterior Pericardiectomy for Postinfective Constrictive Pericarditis: Intermediate-Term Outcomes. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2018 Oct:106(4):1178-1181. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.04.048. Epub 2018 May 16 [PubMed PMID: 29777668]

Hoit BD. Pathophysiology of the Pericardium. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 2017 Jan-Feb:59(4):341-348. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2016.11.001. Epub 2016 Dec 1 [PubMed PMID: 27916673]

Roberts WC. Pericardial heart disease: its morphologic features and its causes. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center). 2005 Jan:18(1):38-55 [PubMed PMID: 16200146]

Hancock EW. A clearer view of effusive-constrictive pericarditis. The New England journal of medicine. 2004 Jan 29:350(5):435-7 [PubMed PMID: 14749449]

Cameron J, Oesterle SN, Baldwin JC, Hancock EW. The etiologic spectrum of constrictive pericarditis. American heart journal. 1987 Feb:113(2 Pt 1):354-60 [PubMed PMID: 3812191]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSagristà-Sauleda J, Angel J, Sánchez A, Permanyer-Miralda G, Soler-Soler J. Effusive-constrictive pericarditis. The New England journal of medicine. 2004 Jan 29:350(5):469-75 [PubMed PMID: 14749455]

Imazio M, Brucato A, Maestroni S, Cumetti D, Belli R, Trinchero R, Adler Y. Risk of constrictive pericarditis after acute pericarditis. Circulation. 2011 Sep 13:124(11):1270-5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.018580. Epub 2011 Aug 15 [PubMed PMID: 21844077]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDoshi S, Ramakrishnan S, Gupta SK. Invasive hemodynamics of constrictive pericarditis. Indian heart journal. 2015 Mar-Apr:67(2):175-82. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2015.04.011. Epub 2015 May 13 [PubMed PMID: 26071303]

Hancock EW. Subacute effusive-constrictive pericarditis. Circulation. 1971 Feb:43(2):183-92 [PubMed PMID: 5540704]

Akhter MW, Nuño IN, Rahimtoola SH. Constrictive pericarditis masquerading as chronic idiopathic pleural effusion: importance of physical examination. The American journal of medicine. 2006 Jul:119(7):e1-4 [PubMed PMID: 16828612]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZagol B, Minderman D, Munir A, D'Cruz I. Effusive constrictive pericarditis: 2D, 3D echocardiography and MRI imaging. Echocardiography (Mount Kisco, N.Y.). 2007 Nov:24(10):1110-4 [PubMed PMID: 18001370]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVeress G, Feng D, Oh JK. Echocardiography in pericardial diseases: new developments. Heart failure reviews. 2013 May:18(3):267-75. doi: 10.1007/s10741-012-9325-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22752511]

Rupprecht L, Putz C, Flörchinger B, Zausig Y, Camboni D, Unsöld B, Schmid C. Pericardiectomy for Constrictive Pericarditis: An Institution's 21 Years Experience. The Thoracic and cardiovascular surgeon. 2018 Nov:66(8):645-650. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1604303. Epub 2017 Aug 6 [PubMed PMID: 28780766]

Ntsekhe M, Shey Wiysonge C, Commerford PJ, Mayosi BM. The prevalence and outcome of effusive constrictive pericarditis: a systematic review of the literature. Cardiovascular journal of Africa. 2012 Jun:23(5):281-5. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2011-072. Epub 2012 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 22240903]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMaisch B, Seferović PM, Ristić AD, Erbel R, Rienmüller R, Adler Y, Tomkowski WZ, Thiene G, Yacoub MH, Task Force on the Diagnosis and Management of Pricardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases executive summary; The Task force on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the European society of cardiology. European heart journal. 2004 Apr:25(7):587-610 [PubMed PMID: 15120056]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMurashita T, Schaff HV, Daly RC, Oh JK, Dearani JA, Stulak JM, King KS, Greason KL. Experience With Pericardiectomy for Constrictive Pericarditis Over Eight Decades. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2017 Sep:104(3):742-750. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.05.063. Epub 2017 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 28760468]