Introduction

Popliteal artery aneurysms are true aneurysms as they involve all layers of the arterial wall.[1] The definition of aneurysmal dilation of the popliteal artery is enlargement of the artery to 1.5 times the average diameter. Thus, with an average diameter ranging between 0.5cm and 1.1cm, a popliteal artery is considered aneurysmal at 1.5cm or greater. In addition to generating emboli leading to acute limb ischemia, these aneurysms are prone to filling with mural thrombus which can occlude the artery.[2][3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Fusiform or saccular dilation of the popliteal artery is due to loss of the mechanical integrity of the vessel wall, leading to dilation of the vessel and ultimately aneurysm degeneration. The direct mechanism is believed to be multifactorial and related to an imbalance of production and degradation of vascular wall constituents including elastin, collagen, glycosaminoglycans and vascular smooth muscle. However, the specific mechanism for the development of popliteal artery aneurysm formation is currently unknown.[1][4]

Epidemiology

Popliteal artery aneurysms are the most frequently encountered peripheral arterial aneurysm, representing approximately 70% of peripheral aneurysms. The incidence is difficult to define given the lack of widespread screening. This clinical entity is still relatively rare with an estimated incidence of 0.1 to 2.8%.[5] Approximately 95% of popliteal artery aneurysms occur in males. Contralateral popliteal aneurysms are present in around 50 to 54% of patients, and abdominal aortic aneurysms are found concurrently in 36 to 51% of patients.[6][7][8][9]

Pathophysiology

Mural thrombus development within the aneurysm sac is multifactorial. The loss of endothelial homeostasis allows for activation of pro-inflammatory and pro-coagulant mediators. Additionally, as the aneurysm sac enlarges, the resultant turbulent flow causes decreased flow velocities along the luminal flow channel. The result of these altered flow mechanics can lead to clot formation, and ultimately to thrombosis and/or embolism.[10][1][11]

Chronic ischemia can develop as a result of repeated thromboembolic events originating from a popliteal artery aneurysm, which occurs in 85% of asymptomatic popliteal artery aneurysms. As repeated insults occur, distal tibial vessels are occluded, leading to progressive limb ischemia and reliance on collateral vessels.[12][13][14] In the event of acute thrombosis of a popliteal artery aneurysm, critical limb ischemia can develop.[15][12][5]

History and Physical

Up to 50% of patients may present with acute or chronic ischemia (ALI). Patients may describe a recent history of worsening claudication, ulceration, rest-pain or blue toe syndrome. A careful physical exam will typically demonstrate a mass in the popliteal fossa. In the event of complete thrombosis, the popliteal mass may not be pulsatile. All patients who present with chronic or acute limb ischemia should undergo evaluation for the presence of a popliteal aneurysm.[16]

The grade of acute limb ischemia dictates management. Clinicians should determine the level of limb viability by examination of the presence of sensory and motor deficits and by the presence or absence of peripheral pulses or Doppler signals. The Rutherford classification for ALI is a grading system that helps clarify the urgency of intervention needed and the viability of the acutely threatened limb.[17] This classification is as follows:

- Grade I: Viable and not immediately threatened. No sensory or motor deficits. Arterial and venous doppler signals are audible

- Grade II: Threatened. Two subcategories exist:

- IIa: Marginally threatened, salvageable if promptly treated. Minimal or no sensory deficits. No motor deficits. Absent arterial signal, with audible venous signal

- IIb: Immediately threatened, salvageable with immediate revascularization. Moderate sensory deficits, associated rest-pain, mild to moderate motor deficits. Absent arterial signal, audible venous signal.

- Grade III: Irreversible, major tissue loss or permanent nerve damage inevitable. Profound sensory and motor deficits present. Absent arterial and venous signals.

Evaluation

All patients with acute limb ischemia secondary to a thrombosed popliteal artery aneurysm should have an arteriogram to evaluate for the presence of suitable outflow vessels for revascularization or bypass. This examination can be done with either CT arteriogram or formal arteriogram, depending on the grade of acute limb ischemia and the urgency of intervention required.[18]

Treatment / Management

The treatment of thrombosed popliteal artery aneurysms is dictated by several factors including the grade of ALI, patient comorbidities, and the patient’s ability to tolerate surgical intervention.[18][19][20][21] In general, patients with grade I or IIa ALI may receive treatment with immediate anticoagulation (e.g., therapeutic heparin drip) and evaluation for surgical bypass or exclusion with arteriography. If suitable inflow and outflow vessels are present, patients should undergo surgical repair during the same hospitalization. If no visible vessels are identifiable, intra-arterial thrombolytics and thrombectomy can be attempted to establish suitable outflow for bypass or exclusion.(B2)

In grade IIb or III acute limb ischemia patients need urgent revascularization for an attempt at limb salvage. Several studies have demonstrated that the use of thrombolytics can improve outcomes in patients with poor arterial outflow on intra-operative arteriogram. The use of thrombolytics in severe ALI depends on clinical judgment and patient factors. The clinician must consider the risks associated with thrombolytics and the patient’s ability to tolerate a delay in revascularization. Most current data suggests that when inadequate outflow shows on an intraoperative arteriogram, thrombolytics with or without mechanical thrombectomy should be attempted to establish an outflow target vessel for bypass. Patients who present with non-viable limbs should be placed on therapeutic anticoagulation, and the limb should be allowed to demarcate to determine the level of amputation required.

The use of saphenous vein graft is preferred when available and is associated with increased patency rates and improved outcomes. Additionally, the use of four-compartment fasciotomies should be a consideration in any patient with significant ischemic time (greater than 4 to 6 hours), or in those with signs/symptoms of compartment syndrome.

Differential Diagnosis

Sources of acute lower extremity arterial occlusion:

- Cardioembolic events

- Thromboembolic

- Hypercoagulability

Prognosis

Several factors impact the outcome of acute limb ischemia secondary to thrombosis of a popliteal artery aneurysm including patient comorbidities, the severity of ischemia at the time of presentation, duration of ischemia, the use of thrombolytics, availability of saphenous vein graft, etc. The incidence of limb loss in those who present with ALI vary greatly among the literature, but reports are as high as 20 to 60%, although most recent studies report an incidence of approximately 14 to 17%. In recent years with advancements in technique and the use of thrombolysis multiple studies have demonstrated favorable long-term outcomes with approximately 68 to 80% 5-year bypass patency rates and greater than 95% limb salvage among those who undergo urgent revascularization.[21][16][20]

Complications

The risk of limb loss in ALI secondary to popliteal artery thrombosis is approximately 14 to 17%. These patients are also at risk for the development of compartment syndrome. The ischemic insults can mask the symptoms of compartment syndrome to the limb. Thus practitioners must have a high degree of suspicion for the risk of compartment syndrome and take the necessary steps to preclude any further insults to the limb. Additionally, the use of thrombolytics has associations with major risks including bleeding, intracranial hemorrhage, and stroke.[21][16][20]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Most current practitioners advocate for the use of anticoagulation or antiplatelet agents following bypass. Additionally, patients who required amputation at any level will need rehabilitation to achieve independence following surgical intervention.

Consultations

Urgent vascular surgery consultation is necessary for any patient with acute limb ischemia.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be informed of the natural history of the disease and recommended for evaluation and surveillance by a vascular surgeon. Patients should receive counseling regarding the risks of developing limb ischemia if aneurysms are left untreated and modifiable risk factors.

Pearls and Other Issues

Patients are classically asymptomatic from these aneurysms and become symptomatic only when the trifurcation vessels are finally all occluded. Thus, amputation rates when presenting with a threatened limb can be quite high. It is therefore imperative that an urgent vascular surgery consultation is obtained to afford the patient their best chance at limb salvage.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

While the rates of limb salvage in a patient who presents with acute limb ischemia secondary to a thrombosed popliteal artery aneurysm have improved significantly over recent years, bypass patency and limb salvage rates are still considerably lower in those treated emergently vs. electively. Therefore detection, monitoring, and elective repair are preferred. Careful examination and identification of patients with popliteal artery aneurysms should prompt referral to a vascular surgeon for further evaluation. Once a patient has suffered ALI an interprofessional team, including physicians, specialists, specialty-trained nursing, and pharmacists involved in patient care is critical to identify, evaluate and treat these patients and guide the case to the best outcomes. [Level V]

Media

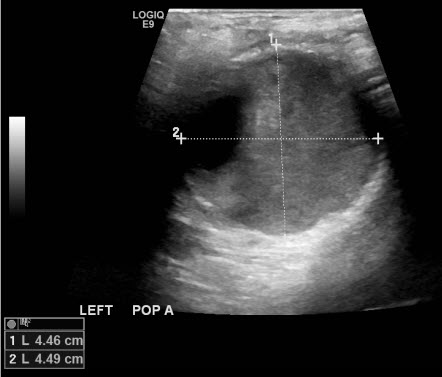

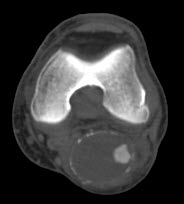

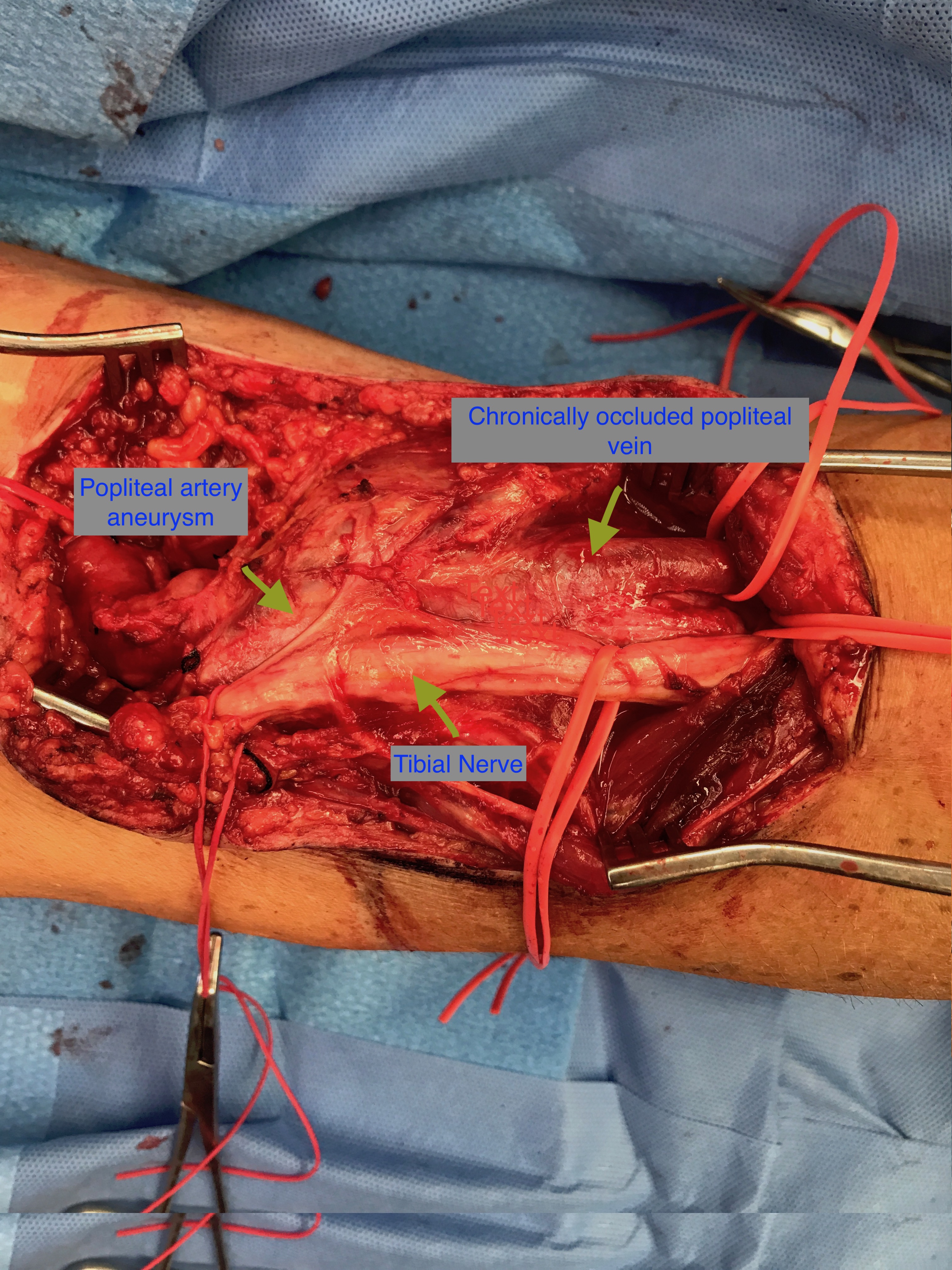

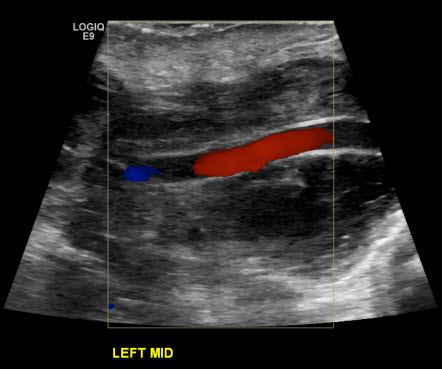

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Jacob T, Hingorani A, Ascher E. Examination of the apoptotic pathway and proteolysis in the pathogenesis of popliteal artery aneurysms. European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery : the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery. 2001 Jul:22(1):77-85 [PubMed PMID: 11461108]

Johnston KW, Rutherford RB, Tilson MD, Shah DM, Hollier L, Stanley JC. Suggested standards for reporting on arterial aneurysms. Subcommittee on Reporting Standards for Arterial Aneurysms, Ad Hoc Committee on Reporting Standards, Society for Vascular Surgery and North American Chapter, International Society for Cardiovascular Surgery. Journal of vascular surgery. 1991 Mar:13(3):452-8 [PubMed PMID: 1999868]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWolf YG, Kobzantsev Z, Zelmanovich L. Size of normal and aneurysmal popliteal arteries: a duplex ultrasound study. Journal of vascular surgery. 2006 Mar:43(3):488-92 [PubMed PMID: 16520160]

Thompson RW, Liao S, Curci JA. Vascular smooth muscle cell apoptosis in abdominal aortic aneurysms. Coronary artery disease. 1997 Oct:8(10):623-31 [PubMed PMID: 9457444]

Kropman RH, Schrijver AM, Kelder JC, Moll FL, de Vries JP. Clinical outcome of acute leg ischaemia due to thrombosed popliteal artery aneurysm: systematic review of 895 cases. European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery : the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery. 2010 Apr:39(4):452-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2009.11.010. Epub 2010 Feb 12 [PubMed PMID: 20153667]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLawrence PF, Lorenzo-Rivero S, Lyon JL. The incidence of iliac, femoral, and popliteal artery aneurysms in hospitalized patients. Journal of vascular surgery. 1995 Oct:22(4):409-15; discussion 415-6 [PubMed PMID: 7563401]

Trickett JP, Scott RA, Tilney HS. Screening and management of asymptomatic popliteal aneurysms. Journal of medical screening. 2002:9(2):92-3 [PubMed PMID: 12133930]

Diwan A, Sarkar R, Stanley JC, Zelenock GB, Wakefield TW. Incidence of femoral and popliteal artery aneurysms in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms. Journal of vascular surgery. 2000 May:31(5):863-9 [PubMed PMID: 10805875]

Huang Y, Gloviczki P, Noel AA, Sullivan TM, Kalra M, Gullerud RE, Hoskin TL, Bower TC. Early complications and long-term outcome after open surgical treatment of popliteal artery aneurysms: is exclusion with saphenous vein bypass still the gold standard? Journal of vascular surgery. 2007 Apr:45(4):706-713; discussion 713-5 [PubMed PMID: 17398379]

Piechota-Polanczyk A, Jozkowicz A, Nowak W, Eilenberg W, Neumayer C, Malinski T, Huk I, Brostjan C. The Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm and Intraluminal Thrombus: Current Concepts of Development and Treatment. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine. 2015:2():19. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2015.00019. Epub 2015 May 26 [PubMed PMID: 26664891]

Diamond SL. Systems Analysis of Thrombus Formation. Circulation research. 2016 Apr 29:118(9):1348-62. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306824. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27126646]

Martelli E, Ippoliti A, Ventoruzzo G, De Vivo G, Ascoli Marchetti A, Pistolese GR. Popliteal artery aneurysms. Factors associated with thromboembolism and graft failure. International angiology : a journal of the International Union of Angiology. 2004 Mar:23(1):54-65 [PubMed PMID: 15156131]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLilly MP, Flinn WR, McCarthy WJ 3rd, Courtney DF, Yao JS, Bergan JJ. The effect of distal arterial anatomy on the success of popliteal aneurysm repair. Journal of vascular surgery. 1988 May:7(5):653-60 [PubMed PMID: 3285037]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceInahara T, Toledo AC. Complications and treatment of popliteal aneurysms. Surgery. 1978 Dec:84(6):775-83 [PubMed PMID: 715697]

Dawson I, Sie RB, van Bockel JH. Atherosclerotic popliteal aneurysm. The British journal of surgery. 1997 Mar:84(3):293-9 [PubMed PMID: 9117288]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRobinson WP 3rd, Belkin M. Acute limb ischemia due to popliteal artery aneurysm: a continuing surgical challenge. Seminars in vascular surgery. 2009 Mar:22(1):17-24. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2008.12.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19298931]

Hardman RL, Jazaeri O, Yi J, Smith M, Gupta R. Overview of classification systems in peripheral artery disease. Seminars in interventional radiology. 2014 Dec:31(4):378-88. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1393976. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25435665]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRavn H, Bergqvist D, Björck M, Swedish Vascular Registry. Nationwide study of the outcome of popliteal artery aneurysms treated surgically. The British journal of surgery. 2007 Aug:94(8):970-7 [PubMed PMID: 17520712]

Gibbons CP. Thrombolysis or immediate surgery for thrombosed popliteal aneurysms? European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery : the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery. 2010 Apr:39(4):458-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2009.12.016. Epub 2010 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 20060334]

Gabrielli R, Rosati MS, Carra A, Vitale S, Siani A. Outcome after preoperative or intraoperative use of intra-arterial urokinase thrombolysis for acute popliteal artery thrombosis and leg ischemia. The Thoracic and cardiovascular surgeon. 2015 Mar:63(2):164-7. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1378189. Epub 2014 Jun 9 [PubMed PMID: 24911902]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDorigo W, Pulli R, Turini F, Pratesi G, Credi G, Innocenti AA, Pratesi C. Acute leg ischaemia from thrombosed popliteal artery aneurysms: role of preoperative thrombolysis. European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery : the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery. 2002 Mar:23(3):251-4 [PubMed PMID: 11914013]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence