Introduction

Cardioversion is the process of converting a heart that is in an abnormal and potentially dangerous rhythm into a normal sinus rhythm. The normal heart rate comes from the sinoatrial node and progresses through the right atrium to the atrioventricular node and then through the conduction system to the ventricles. For a variety of reasons, including structural changes to the heart, medications, and tissue damage, the heart can develop a rhythm that does not follow the normal pattern and can lead to heart rates that are too fast, too slow, or are irregular. Heart rates that are irregular or too fast are candidates for cardioversion. Slow heart rates are candidates for cardiac pacing.

With any dysrhythmia, reversible causes of the rhythm abnormality should be sought, including infection, pulmonary embolus, and myocardial infarction.[1][2][3]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Rhythms that can be cardioverted are atrial fibrillation/flutter (AF), supraventricular tachycardias (SVT), ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation. Synchronized cardioversion is appropriate for all of these rhythms except ventricular fibrillation or unstable ventricular tachycardia.

Indications

Three types of cardioversion can be used to attempt to change the rhythm of the heart. The initial evaluation for which type to use is the patient’s hemodynamic status. If the patient is hypotensive, has chest pain, altered mental status, or heart failure, immediate electrical cardioversion should be considered. Electrical cardioversion can be used for patients that are hemodynamically stable as well and is most likely to be successful but requires sedation. For patients that are hemodynamically stable, there are two additional options: for patients in supraventricular tachycardia, physical maneuvers that increase vagal tone can be attempted, or for SVT and AF, chemical cardioversion may be attempted. Maneuvers to increase vagal tone include having the person bear down and exhale against a closed glottis as if they are straining to have a bowel movement (Valsalva maneuver), or pressing on the carotid artery at the level of the bifurcation (carotid artery massage).

Chemical cardioversion involves treating with a medication to convert the rhythm back into a normal sinus rhythm. The success of the chemical cardioversion depends on many factors, including the underlying cause of the arrhythmia, and the duration of the arrhythmia.[4][5][6]

Contraindications

Pharmacological cardioversion is ideal for stable patients. For those who are hemodynamically unstable, immediate electrical cardioversion is indicated.

Equipment

There are many types of pharmacological agents available for acute cardioversion in patients with atrial arrhythmias, but all methods of pharmacological cardioversion are associated with risks of proarrhythmia. With the use of oral agents, there is a 2% risk of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Thus, it is vital to perform pharmacological cardioversion in a monitored setting like the intensive care unit. A defibrillator must be available nearly. Equipment for ACLS must be in the room. After successful cardioversion, the patient should be observed for at least 24 to 48 hours or until the QT interval normalizes.

One may use oral or intravenous agents. In the outpatient setting. Intravenous (IV) medications can be used, but the ECG and blood pressure must be recorded continuously.

Personnel

Pharmacological cardioversion should be performed by a cardiologist who has experience dealing with arrhythmias. The cardiologist must be familiar with the different antiarrhythmic agents and be aware of the potential arrhythmogenic potential of cardioversion.

Preparation

Pharmacological cardioversion can be done both as an inpatient or outpatient. Most experts recommend performing the procedure in a monitored setting. The patient should be fasting prior to the procedure. Both ECG and BP cuffs should be attached, and the patient must have two peripheral intravenous lines.

Technique or Treatment

Narrow Complex Regular Tachycardia

This rhythm is sinus tachycardia, multifocal atrial tachycardia (in which therapy is directed toward treating the underlying disease process), or supraventricular tachycardia. Supraventricular tachycardia is a term for a collection of clinically similar rhythms. This rhythm is defined as a regular rhythm with narrow QRS complexes and a rate that is usually greater than 150/min. It is treated with adenosine, which must be pushed rapidly. The half-life of adenosine is very short, and the medication is only effective if given rapidly. The initial dose is 6 mg, which may be followed by two attempts of 12 mg if unsuccessful. An alternative treatment is Cardizem 0.25 mg/kg IV, or metoprolol 5 mg IV.

Regular Wide Complex Tachycardia

This rhythm has a regular rhythm with wide QRS complexes that are uniform in shape and may represent several underlying rhythms. The treatment for the stable patient is with adenosine in the same manner as a narrow-complex supraventricular tachycardia. If unsuccessful, procainamide may be used to attempt cardioversion. Procainamide should not be used if the rhythm is thought to be from an overdose of tricyclic antidepressants.

Narrow Complex Irregular Tachycardia

This is most likely from atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter with variable heart block. Due to the risk of thrombus formation in the left atrial appendage during atrial fibrillation, cardioversion is rarely used in the emergency department. If the duration of the rhythm is less than 48 hours, the clinician may consider electrical cardioversion or may provide rate control and anticoagulation with delayed cardioversion from a cardiologist. In patients age 65 or older, there does not appear to be a benefit of rhythm control over rate control. If the duration of the rhythm is greater than 48 hours, cardioversion should not be attempted due to the risk of stroke from left atrial thrombus. If attempting chemical cardioversion in the emergency department for atrial fibrillation, procainamide may be used but is only approximately 60% effective. Individuals who are cardioverted in the emergency department should be considered for concomitant anticoagulation at least for the ensuing weeks in which there is still a risk of clot embolus from the ongoing stasis of the left atrium.

Irregular Wide Complex or Polymorphic Tachycardia

This rhythm either has an irregular rhythm or QRS complexes that are irregular in shape. This may be from atrial fibrillation combined with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome or atrial fibrillation with bundle branch block, torsades de pointes and ventricular fibrillation. If the rhythm is Wolff-Parkinson-White, this condition can be worsened by the use of nodal blocking agents and a cardiology consult should be obtained for people in this rhythm. Procainamide or amiodarone may be attempted. However, this patient may need electrical cardioversion. If the rhythm is determined to be torsades de pointes, the patient should be treated with an infusion of IV magnesium, 2g to 4 g over 5 to 10 minutes.

Clinical Significance

Pharmacological cardioversion does carry a risk of embolic events, resulting in a stroke. However, this risk is small in patients with atrial arrhythmias less than 48 hours. But for all those with chronic atrial arrhythmias, the risk of stroke is high. Patients with persistent atrial arrhythmias of more than 48 hours or unknown duration should be treated with anticoagulation for at least 3 weeks before pharmacological cardioversion. Also, anticoagulation should be continued for 4 weeks after the procedure, since the atria do take several weeks to recover their function and shape. The INR should be maintained between 2 to 3.[7][8][9]

A transesophageal echo (TEE) may be performed to exclude the presence of thrombus in patients with atrial arrhythmias that are considered for cardioversion. However, the results of a TEE should be interpreted with care as embolic events have occurred in patients despite a negative result on the echo. Thus, a negative echo does not obviate the need for anticoagulation.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Pharmacological cardioversion is usually performed by the cardiologist but dedicated nursing staff are required to monitor the patient and assist in the procedure. Prior to pharmacological conversion, an echo is highly recommended. Pharmacological cardioversion is ideal for hemodynamically stable patients. The pharmacist must emphasize the importance of medication compliance because untreated atrial arrhythmias can predispose people to a stroke. Prior to cardioversion, the pharmacist should evaluate for potential drug-drug interactions that may diminish the chances of success. The patient has to be placed on an oral anticoagulant after the procedure and should be followed up the primary care provider to ensure that the INR is therapeutic. The pharmacist, nurse practitioner and the primary care provider should never alter the dose of the antiarrhythmic agent without first consulting with the patient's cardiologist Patient education is key, and the nurse should assist in making sure the family and patient understand the procedure then assist with education in regards to changes in behavior that will improve long-term outcomes. An interprofessional team approach will provide the best care for these patients. [10]

Media

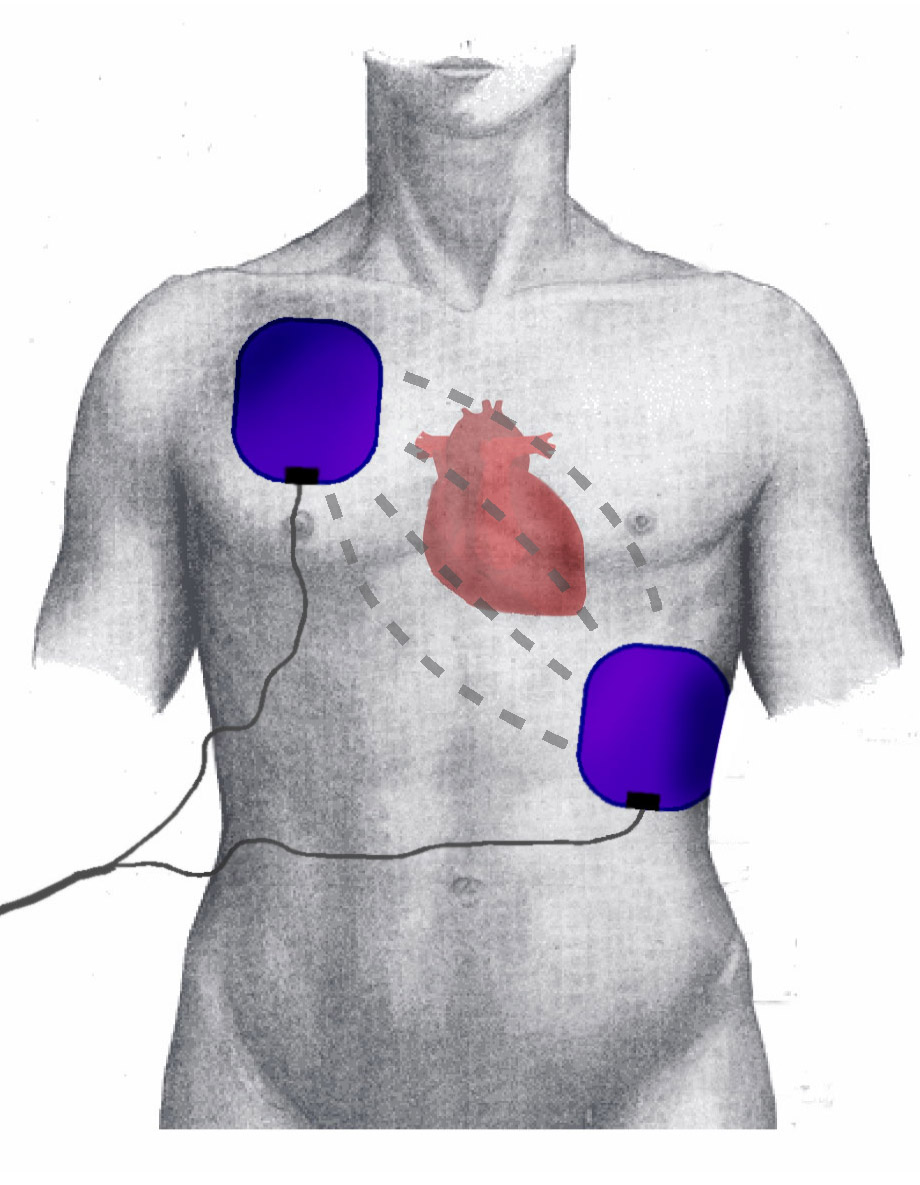

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Vitali F, Serenelli M, Airaksinen J, Pavasini R, Tomaszuk-Kazberuk A, Mlodawska E, Jaakkola S, Balla C, Falsetti L, Tarquinio N, Ferrari R, Squeri A, Campo G, Bertini M. CHA2DS2-VASc score predicts atrial fibrillation recurrence after cardioversion: Systematic review and individual patient pooled meta-analysis. Clinical cardiology. 2019 Mar:42(3):358-364. doi: 10.1002/clc.23147. Epub 2019 Feb 11 [PubMed PMID: 30597581]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKowey PR, Ahmad S. Cardioversion of obese patients: What is the weight of evidence? Journal of cardiovascular electrophysiology. 2019 Feb:30(2):162-163. doi: 10.1111/jce.13814. Epub 2018 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 30556226]

Andrade JG, Verma A, Mitchell LB, Parkash R, Leblanc K, Atzema C, Healey JS, Bell A, Cairns J, Connolly S, Cox J, Dorian P, Gladstone D, McMurtry MS, Nair GM, Pilote L, Sarrazin JF, Sharma M, Skanes A, Talajic M, Tsang T, Verma S, Wyse DG, Nattel S, Macle L, CCS Atrial Fibrillation Guidelines Committee. 2018 Focused Update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation. The Canadian journal of cardiology. 2018 Nov:34(11):1371-1392. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2018.08.026. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30404743]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCapucci A, Cipolletta L, Guerra F, Giannini I. Emerging pharmacotherapies for the treatment of atrial fibrillation. Expert opinion on emerging drugs. 2018 Mar:23(1):25-36. doi: 10.1080/14728214.2018.1446941. Epub 2018 Mar 13 [PubMed PMID: 29508636]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrunetti ND, Tarantino N, De Gennaro L, Correale M, Santoro F, Di Biase M. Direct oral anti-coagulants compared to vitamin-K antagonists in cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: an updated meta-analysis. Journal of thrombosis and thrombolysis. 2018 May:45(4):550-556. doi: 10.1007/s11239-018-1622-5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29404874]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMarkey GC, Salter N, Ryan J. Intravenous Flecainide for Emergency Department Management of Acute Atrial Fibrillation. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2018 Mar:54(3):320-327. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.11.016. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29269083]

Balik M, Matousek V, Maly M, Brozek T. Management of arrhythmia in sepsis and septic shock. Anaesthesiology intensive therapy. 2017:49(5):419-429. doi: 10.5603/AIT.a2017.0061. Epub 2017 Nov 18 [PubMed PMID: 29151002]

Gibson CM, Basto AN, Howard ML. Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Cardioversion: A Review of Current Evidence. The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 2018 Mar:52(3):277-284. doi: 10.1177/1060028017737095. Epub 2017 Oct 12 [PubMed PMID: 29025267]

Grandi E, Maleckar MM. Anti-arrhythmic strategies for atrial fibrillation: The role of computational modeling in discovery, development, and optimization. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2016 Dec:168():126-142. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.09.012. Epub 2016 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 27612549]

Verbrugge FH, Mullens W. Combined management of atrial fibrillation and heart failure: case studies. Heart failure reviews. 2014 May:19(3):331-9. doi: 10.1007/s10741-013-9410-y. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24101029]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence