Introduction

Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS) refers to a subtype of tenosynovial giant cell tumors that diffusely affect the soft tissue lining of joints and tendons. PVNS most commonly affects the knee, hip, and ankle joints and is insidious in onset, with symptoms often being present for years before diagnosis.[1][2] Furthermore, PVNS is more aggressive compared to the other major subtype of tenosynovial giant cell tumors, giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath (GCT-TS). According to a 1980 report, PVNS affects roughly 9.2 new people per million in the United States each year.[1] Even after treatment, the recurrence rate of PVNS ranges from 14 to 55%.[2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Pigmented villonodular synovitis has been shown to have neoplastic components. Translocations of chromosome 1p13 are present in the majority of PVNS cases with the endpoint effect of overexpressing colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF1). As CSF-1 becomes overexpressed, clusters of aberrant cells form to create focal areas of soft tissue hyperplasia in the synovial cells lining joints.[3]

Epidemiology

Due to its slow onset, the median time of definitive diagnosis from the onset of symptoms to definitive diagnosis has been shown to be 18 months.[4] There is conflicting data regarding the gender distribution of pigmented villonodular synovitis. Some studies suggest that male and female genders are affected at equal rates,[3] while others suggest females are slightly more predisposed, but only in the context of localized disease.[5][6] Pigmented villonodular synovitis has been consistently shown to have a lower incidence in pediatric populations. As a result, it gets more frequently misdiagnosed in children.[7]

Histopathology

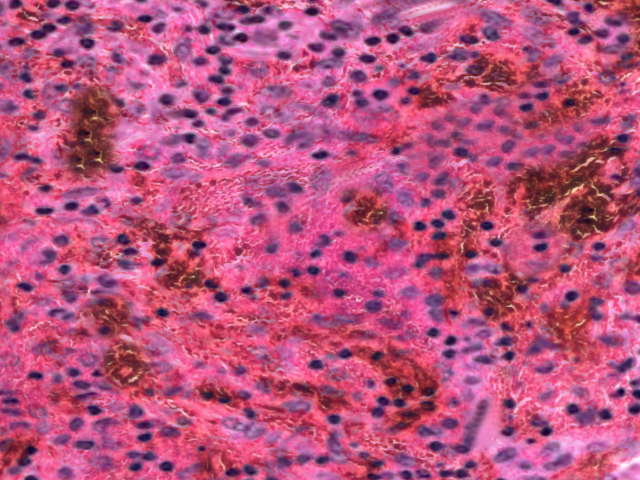

Synovial fluid analysis in pigmented villonodular synovitis most often has a dark brown or hemorrhagic color.[8] Microscopic workup reveals an assortment of mononuclear cells, macrophages with extensive hemosiderin stores, and multinucleated osteoclast-type giant cells.[9] Specifically, hemosiderin deposits result from the episodic nature of the disease. As repeated bleeding into the joint occurs, hemoglobin breaks down to form large deposits of iron in surrounding tissues. The resulting hemosiderin-laden parenchyma is a direct reflection of recurrent hemarthrosis in patients with PVNS.[8][10]

History and Physical

The tumor of pigmented villonodular synovitis is slow-growing, and, early on in the disease course, the patient presents with unexplained painless swelling in the affected joint.[6] As the tumor expands, however, pain and swelling add to cause moderate to severe range of motion limitations in the affected area.[6][9] As the disease progresses, recurrent hemarthrosis leads to worsening joint stiffness and moderate to severe joint destruction.[11] A single joint presentation is the most common, but rarely PVNS can present polyarthropically.[7] Since the onset of symptoms in PVNS is insidious, patient history often includes an extensive workup for other causes of joint pain.[12] Pigmented villonodular synovitis typically occurs in the large joint of the upper and lower extremities. Most commonly, the disease affects the knee in the patellofemoral compartment at the infrapatellar fat pad.[6]

Evaluation

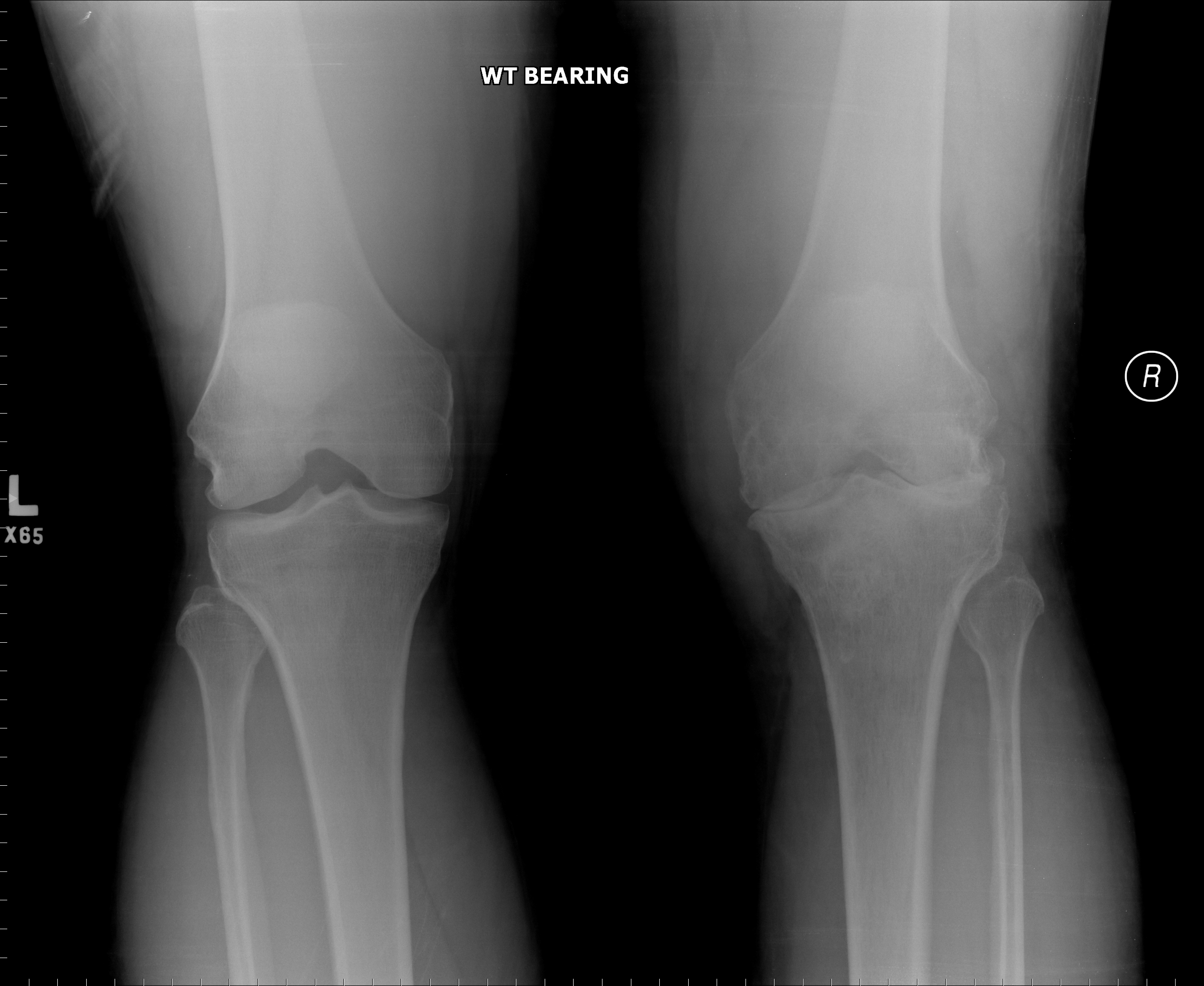

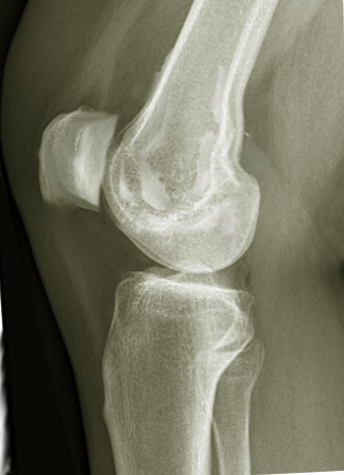

Clinicians typically pigmented villonodular synovitis through a combination of several radiographic modalities. Initial X-ray studies show signs of soft tissue swelling in addition to boney erosion around the affected joint.[9] MRI imagining is the most sensitive imagining study. Classically, MRI demonstrates joint effusion, hemosiderin deposits, expansion of the synovium, and boney erosion. Routine blood markers for inflammation, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C reactive protein, are not elevated in the majority of patients, despite the clinical appearance of soft tissue swelling.[6][4] Several authors have suggested a link between a prior joint injury and the development of PVNS, but this correlation has not been proven to be consistent across investigators.[9][13] Incidental hemarthrosis from aspiration of a chronically inflamed joint can also provide an important diagnostic clue.[8]

Treatment / Management

The gold standard of treatment for pigmented villonodular synovitis has traditionally been surgical excision with total synovectomy of the affected joint, either with an open or arthroscopic approach.[14] While both of these methods have a similar reoccurrence rate of PVNS post-surgery, the arthroscopic procedure has consistently demonstrated better functional and range of motion outcomes for the patient.[15] However, even after surgery, PVNS has a recurrence rate of up to 50%, prompting investigators to explore additional treatment options.[6] When used as monotherapy, external beam radiation has demonstrated local control of up to 95.1% when dosed from 30 Gy to 50 Gy.[16] Radiation therapy has also been shown to reduce PVNS recurrence post-surgical synovectomy significantly.[16] The elucidation of the CSF-1 pathway has lead to the investigation of multiple systemic therapies, including monoclonal antibodies and tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Amongst these agents, emactuzumab and PLX3397 show promise.[6] Emactuzumab is a monoclonal antibody that directly binds the CSF-1 receptor on the surface of macrophages, thus reducing or eliminating the effects of aberrant CSF-1 production. In a recent phase 1 trial, 26 out of 28 patients with PVNS had an objective response to treatment with emactuzumab.[6] PLX3397, which works by blocking molecular endpoints of CSF-1, demonstrated not only a well-tolerated side effect profile but also a clinical response in 52% of patients.[6] Most recently, the use of pexidartinib, a CSF-1 receptor antagonist, was approved by the FDA in August 2019 for use in patients with extensive disease who are not likely to benefit from surgical intervention.[17](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Rheumatoid arthritis, septic joints, hemarthrosis, and other neoplasia can all mimic the clinical features of pigmented villonodular synovitis upon clinical inspection.[7] Even with ideal radiographic and diagnostic studies, pigmented villonodular synovitis can get misdiagnosed as a ganglion, schwannoma, or hemangioma.[18]

Prognosis

Pigmented villonodular synovitis demonstrates a locally destructive process but is rarely fatal. PVNS is primarily a disease of quality of life as it can lead to difficulty with activities of daily living and an overall decrease in quality of life.[6]

Complications

If left untreated, the complications of pigmented villonodular synovitis include moderate to severe joint deformity, degenerative articular changes, and osteoarthritis.[14] If arthritic changes produce severe erosion of articular surfaces, the ensuing cortical bone destruction can lead to the need for arthrodesis or amputation.[3] Additional complications of PVNS are related to the interventions themselves. Systemic treatment with pexidartinib carries the primary risk factor of hepatic toxicity with close monitoring of liver enzymes being a critical aspect of management.[3] Complications from surgery depend on whether the clinician pursues an arthroscopic or open approach. Open surgeries correlate with more extended hospital stays and prolonged rehabilitation. Arthroscopic surgeries require technical expertise and may not be able to remove large masses with local tissue invasion.[16] Metastasis of PVNS, both malignant and benign, is extremely rare. However, there have been documented cases of metastasis to the lung, muscles, and lymph nodes.[19]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients need to be informed of both surgical and systemic treatments for pigmented villonodular synovitis so that they can make the most informed decision. If surgery is elected, the surgeon should discuss the pros and cons of open versus arthroscopic knee surgery with the patient based on the operability of the tumor itself and the desired functional outcome. It is equally important to discuss the risks of the surgery itself about the benefits. Also, the high recurrence rate of PVNS despite surgical interventions requires emphasis. Since PVNS can mimic many other disease pathologies and often gets misdiagnosed, it may be necessary for patients to seek providers from multiple specialties to come up with the best diagnostic and treatment plan.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The ideal outcome for a patient diagnosed with pigmented villonodular synovitis results from an analysis of patient goals, realistic functional outcomes, the decision for surgery or systemic treatment, and care coordination across multiple specialties, utilizing an interprofessional team approach. The recommendation is that establishing a diagnosis is optimally from the interprofessional collaborative effort of the primary care doctor, radiologists, pathologists, and rehab team.[20][21] [Level 2] By ordering and reviewing the correct imagining studies and clinical picture, the care team can decide if the decision to further biopsy the lesion is needed. Once a diagnosis is determined, it is important to consider the functional outcome of surgery vs. systemic treatment. The best approach for this is through a discussion of patient care goals and the risks and benefits of surgical vs. systemic intervention. For example, in difficult cases of PVNS that will not be likely to improve with surgery, the care team should consider the use of pexidartinib in patients without major hepatic co-morbidities.[17] The pharmacy should have involvement in medical treatment, verifying dosing, administration, and checking for drug interactions or other contraindications. Nursing staff with specialty training in orthopedics and surgery can assist the clinician before diagnosis, during treatment in both medical and surgical cases, and provide ongoing support, evaluation, and counsel following surgery or during medical management. If surgery is the chosen option, physical therapy is highly recommended to regain function and muscle strength. Pain control management should involve the pharmacist, and the patient is encouraged to maintain a healthy weight. All these disciplines collaborating in an interprofessional team paradigm, ensure the best possible patient outcomes, regardless of the management tact chosen. [Level 5]

Increasing the role of the patient in constructing a collaborative treatment will not only be helpful to solidify patient compliance in pigmented villonodular synovitis but also across the spectrum of disease in general. It is strongly advised to develop and continue a patient-physician collaboration from diagnosis through treatment and management of PVNS.[22] [Level 2]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Burton TM, Ye X, Parker ED, Bancroft T, Healey J. Burden of Illness Associated with Tenosynovial Giant Cell Tumors. Clinical therapeutics. 2018 Apr:40(4):593-602.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.03.001. Epub 2018 Mar 24 [PubMed PMID: 29580718]

Staals EL, Ferrari S, Donati DM, Palmerini E. Diffuse-type tenosynovial giant cell tumour: Current treatment concepts and future perspectives. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2016 Aug:63():34-40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.04.022. Epub 2016 Jun 5 [PubMed PMID: 27267143]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWest RB, Rubin BP, Miller MA, Subramanian S, Kaygusuz G, Montgomery K, Zhu S, Marinelli RJ, De Luca A, Downs-Kelly E, Goldblum JR, Corless CL, Brown PO, Gilks CB, Nielsen TO, Huntsman D, van de Rijn M. A landscape effect in tenosynovial giant-cell tumor from activation of CSF1 expression by a translocation in a minority of tumor cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006 Jan 17:103(3):690-5 [PubMed PMID: 16407111]

Xie GP, Jiang N, Liang CX, Zeng JC, Chen ZY, Xu Q, Qi RZ, Chen YR, Yu B. Pigmented villonodular synovitis: a retrospective multicenter study of 237 cases. PloS one. 2015:10(3):e0121451. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121451. Epub 2015 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 25799575]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMastboom MJL, Verspoor FGM, Verschoor AJ, Uittenbogaard D, Nemeth B, Mastboom WJB, Bovée JVMG, Dijkstra PDS, Schreuder HWB, Gelderblom H, Van de Sande MAJ, TGCT study group. Higher incidence rates than previously known in tenosynovial giant cell tumors. Acta orthopaedica. 2017 Dec:88(6):688-694. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2017.1361126. Epub 2017 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 28787222]

Brahmi M, Vinceneux A, Cassier PA. Current Systemic Treatment Options for Tenosynovial Giant Cell Tumor/Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis: Targeting the CSF1/CSF1R Axis. Current treatment options in oncology. 2016 Feb:17(2):10. doi: 10.1007/s11864-015-0385-x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26820289]

Zhao L, Zhou K, Hua Y, Li Y, Mu D. Multifocal pigmented villonodular synovitis in a child: A case report. Medicine. 2016 Aug:95(33):e4572. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004572. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27537585]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFrassica FJ, Bhimani MA, McCarthy EF, Wenz J. Pigmented villonodular synovitis of the hip and knee. American family physician. 1999 Oct 1:60(5):1404-10; discussion 1415 [PubMed PMID: 10524485]

Al Farii H, Zhou S, Turcotte R. The surgical outcome and recurrence rate of tenosynovial giant cell tumor in the elbow: a literature review. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2019 Sep:28(9):1835-1840. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2019.05.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31447124]

Ramesh B, Shetty S, Bastawrous SS. Pigmented villonodular synovitis of the knee in a patient on oral anticoagulation therapy: a case report. Journal of medical case reports. 2009 Nov 13:3():121. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-3-121. Epub 2009 Nov 13 [PubMed PMID: 20062764]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHoudek MT, Scorianz M, Wyles CC, Trousdale RT, Sim FH, Taunton MJ. Long-term outcome of knee arthroplasty in the setting of pigmented villonodular synovitis. The Knee. 2017 Aug:24(4):851-855. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2017.04.019. Epub 2017 May 25 [PubMed PMID: 28552192]

Willimon SC, Schrader T, Perkins CA. Arthroscopic Management of Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis of the Hip in Children and Adolescents. Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine. 2018 Mar:6(3):2325967118763118. doi: 10.1177/2325967118763118. Epub 2018 Mar 21 [PubMed PMID: 29594178]

Myers BW, Masi AT. Pigmented villonodular synovitis and tenosynovitis: a clinical epidemiologic study of 166 cases and literature review. Medicine. 1980 May:59(3):223-38 [PubMed PMID: 7412554]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChang JS, Higgins JP, Kosy JD, Theodoropoulos J. Systematic Arthroscopic Treatment of Diffuse Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis in the Knee. Arthroscopy techniques. 2017 Oct:6(5):e1547-e1551. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2017.06.029. Epub 2017 Oct 12 [PubMed PMID: 29354472]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYang B, Liu D, Lin J, Jin J, Weng XS, Qian WW, Qian J. Surgical treatment of diffuse pigmented villonodular synovitis of the knee. Zhongguo yi xue ke xue yuan xue bao. Acta Academiae Medicinae Sinicae. 2015 Apr:37(2):234-9. doi: 10.3881/j.issn.1000-503X.2015.02.017. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25936715]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMollon B, Lee A, Busse JW, Griffin AM, Ferguson PC, Wunder JS, Theodoropoulos J. The effect of surgical synovectomy and radiotherapy on the rate of recurrence of pigmented villonodular synovitis of the knee: an individual patient meta-analysis. The bone & joint journal. 2015 Apr:97-B(4):550-7. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.97B4.34907. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25820897]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTap WD, Gelderblom H, Palmerini E, Desai J, Bauer S, Blay JY, Alcindor T, Ganjoo K, Martín-Broto J, Ryan CW, Thomas DM, Peterfy C, Healey JH, van de Sande M, Gelhorn HL, Shuster DE, Wang Q, Yver A, Hsu HH, Lin PS, Tong-Starksen S, Stacchiotti S, Wagner AJ, ENLIVEN investigators. Pexidartinib versus placebo for advanced tenosynovial giant cell tumour (ENLIVEN): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet (London, England). 2019 Aug 10:394(10197):478-487. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30764-0. Epub 2019 Jun 19 [PubMed PMID: 31229240]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceÇevik HB, Kayahan S, Eceviz E, Gümüştaş SA. Tenosynovial giant cell tumor in the foot and ankle. Foot and ankle surgery : official journal of the European Society of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. 2020 Aug:26(6):712-716. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2019.08.014. Epub 2019 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 31526689]

Chen EL, de Castro CM 4th, Hendzel KD, Iwaz S, Kim MA, Valeshabad AK, Shokouh-Amiri M, Xie KL. Histologically benign metastasizing tenosynovial giant cell tumor mimicking metastatic malignancy: A case report and review of literature. Radiology case reports. 2019 Aug:14(8):934-940. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2019.05.013. Epub 2019 May 24 [PubMed PMID: 31193787]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZwarenstein M, Goldman J, Reeves S. Interprofessional collaboration: effects of practice-based interventions on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2009 Jul 8:(3):CD000072. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000072.pub2. Epub 2009 Jul 8 [PubMed PMID: 19588316]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCao V, Tan LD, Horn F, Bland D, Giri P, Maken K, Cho N, Scott L, Dinh VA, Hidalgo D, Nguyen HB. Patient-Centered Structured Interdisciplinary Bedside Rounds in the Medical ICU. Critical care medicine. 2018 Jan:46(1):85-92. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002807. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29088002]

Arbuthnott A, Sharpe D. The effect of physician-patient collaboration on patient adherence in non-psychiatric medicine. Patient education and counseling. 2009 Oct:77(1):60-7. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.022. Epub 2009 Apr 22 [PubMed PMID: 19395222]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence